Children with epilepsy present greater prevalence of sleep disorders than the general population. Their diagnosis is essential, since epilepsy and sleep disorders have a bidirectional relationship.

ObjectiveDetermine the incidence of sleep disorders and poor sleep habits in children with epilepsy.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study of patients under 18 years of age with epilepsy, assessing sleep disorders using the Spanish-language version of the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC), and sleep habits using an original questionnaire.

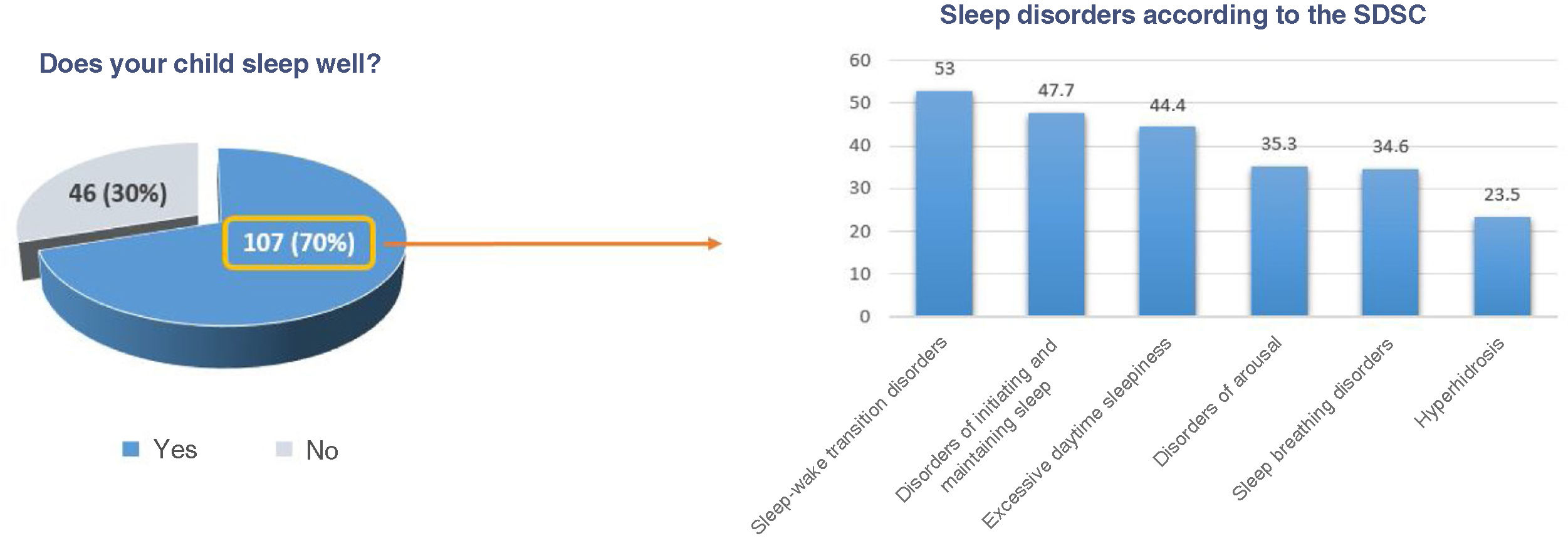

ResultsThe sample included 153 patients. Eighty-four percent of our sample presented some type of sleep alteration. The most frequent alterations were sleep-wake transition disorders (53%), sleep initiation and maintenance disorders (47.7%), and daytime sleepiness (44.4%). In 70% of cases, the patients’ parents reported that their child “slept well,” although sleep disorders were detected in up to 75.7% of these patients. Many patients had poor sleep habits, such as using electronic devices in bed (16.3%), requiring the presence of a family member to fall asleep (39%), or co-sleeping or sharing a room (23.5% and 30.5%, respectively). Those with generalised epilepsy, refractory epilepsy, nocturnal seizures, and intellectual disability were more likely to present sleep disorders. In contrast, poor sleep habits were frequent regardless of seizure characteristics.

ConclusionsSleep disorders and poor sleep habits are common in children with epilepsy. Their treatment can lead to an improvement in the quality of life of the patient and his/her family, as well as an improvement in the prognosis of epilepsy.

Los niños con epilepsia tienen más trastornos del sueño (TS) que la población sana. Es fundamental su diagnóstico, ya que la epilepsia y los TS tienen una relación bidireccional.

ObjetivoDeterminar la incidencia de TS y malos hábitos de sueño en niños con epilepsia.

MétodoEstudio transversal de pacientes menores de 18 años con epilepsia sobre TS, mediante la versión española de Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC), y sobre hábitos de sueño, mediante cuestionario de elaboración propia.

ResultadosLa muestra incluyó 153 pacientes. El 84% de la población estudiada presentaba alterado algún aspecto del sueño. Lo más frecuente fueron las alteraciones en la transición sueño-vigilia (53%), en el inicio-mantenimiento del sueño (47.7%) y la somnolencia diurna (44.4%). Un 70% de los padres de los pacientes referían que su hijo “dormía bien”, pero en este grupo se detectaron TS hasta en el 75.7%. Muchos de los pacientes tenían hábitos de sueño poco saludables, como dormirse con dispositivos electrónicos (16.3%), precisar presencia familiar para dormirse (39%) o dormir en colecho o cohabitación (23,5% y 30,5% respectivamente). Aquellos con epilepsias generalizadas, refractarias, crisis nocturnas y discapacidad intelectual presentaron mayor probabilidad de presentar TS. En cambio, los malos hábitos de sueño fueron frecuentes independientemente de las características de la epilepsia.

ConclusionesLos TS y los malos hábitos de sueño son frecuentes en niños con epilepsia. Su tratamiento puede conllevar una mejoría en la calidad de vida del paciente y su familia, así como una mejoría en el pronóstico de la epilepsia.

Sleep disorders are highly prevalent in the paediatric population, especially in children with neurological diseases. At the same time, sleep is increasingly recognised as a key factor in neurodevelopment. Patients with neurological diseases, especially epilepsy, represent one of the populations with the greatest vulnerability to sleep disorders; in these patients, comprehensive care may result in significant improvements in quality of life.1,2

Epilepsy and sleep disorders have a bidirectional relationship. The incidence of sleep disorders is higher among patients with epilepsy than in the general population.3–6 At the same time, children with epilepsy present a higher percentage of behavioural alterations, cognitive problems, and learning difficulties (mainly attention problems and hyperactivity), with rates 24%–66% higher than in the general population; these alterations are strongly associated with the presence of insomnia or hypersomnia.7,8 Nocturnal seizures, nocturnal epileptiform activity, and in many cases antiepileptic drugs seem to be responsible for sleep fragmentation, as well as difficulty falling asleep, which results in excessive daytime sleepiness and cognitive and behavioural alterations.9,10

Likewise, the presence of sleep alterations results in poorer control of epilepsy. Sleep disorders seem to be directly associated with seizure control. Several researchers have suggested an association between insomnia, chronic sleep deprivation, and secondary excessive daytime sleepiness, on the one hand, and higher numbers of epileptic seizures, on the other, hypothesising that improvements in these sleep disorders may result in lower seizure frequency.11 Segal et al.12 conducted a study with 27 children with sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS) treated with adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy; 3 months after surgery, 70.3% of them presented a reduction in seizure frequency.12 Polysomnography studies show that patients with sleep disorders present shorter duration of REM sleep, which increases epileptiform activity during sleep.13

Although sleep alterations seem to have a direct impact not only on epilepsy itself but also on the quality of life of these children and their families,14 the association has not been studied in large samples; furthermore, few studies have analysed the characteristics more strongly associated with poorer sleep quality or sleep hygiene in this population.15 This study analyses the incidence of sleep disorders and sleep patterns in paediatric patients with epilepsy, as well as the characteristics of epilepsy that result in poorer sleep quality.16

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study of patients younger than 18 years with epilepsy who visited the neurology department of Hospital Niño Jesús in Madrid between August and November 2019; all the patients studied participated voluntarily.

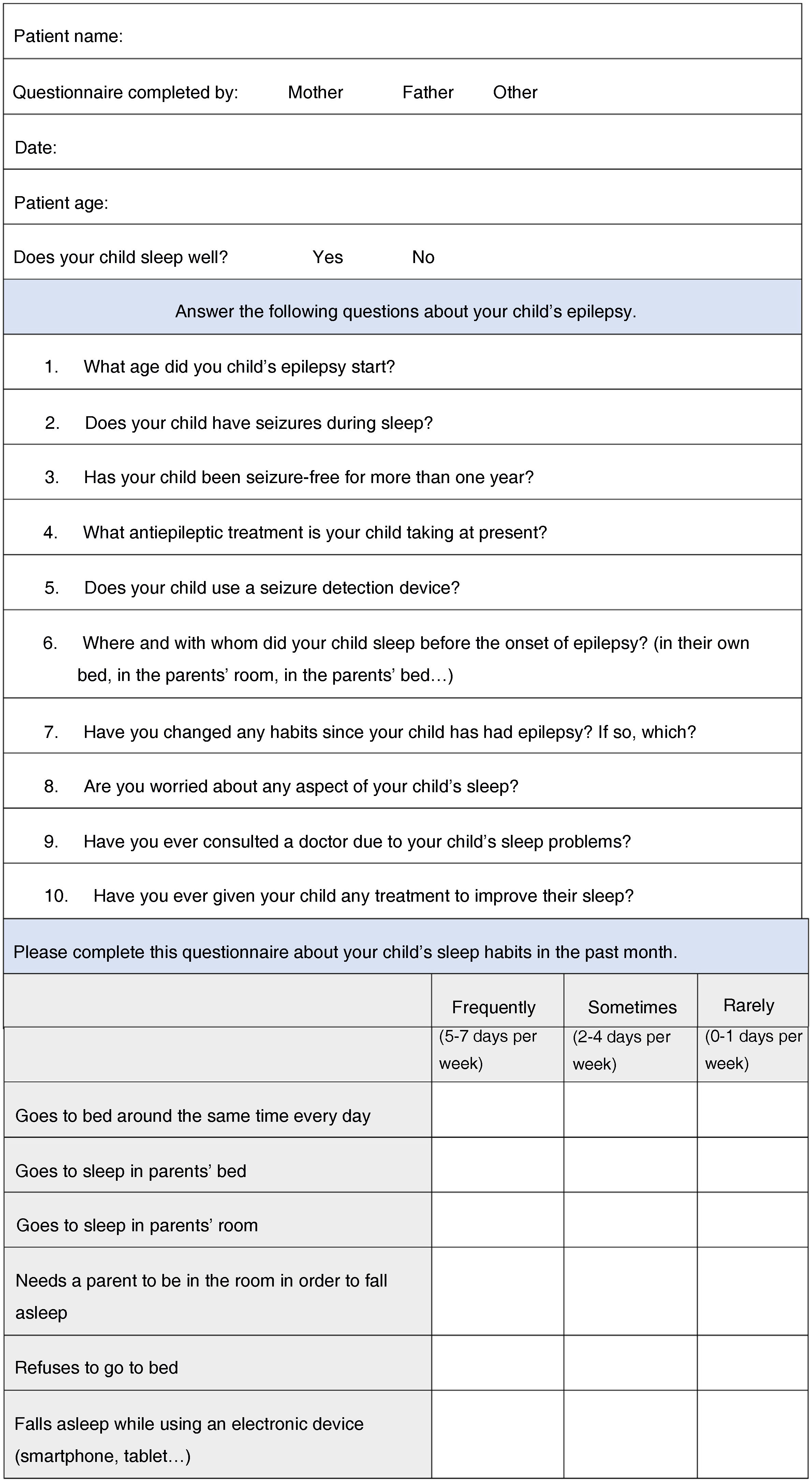

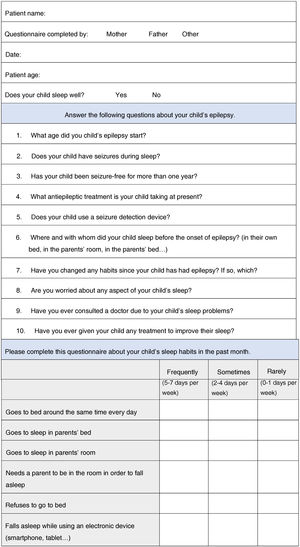

During the consultation, patients’ parents were asked to complete an ad hoc questionnaire about the child’s sleep hygiene, which included a closed-ended question about sleep quality (Does your child sleep well? Yes/No) (Fig. 1). Parents were subsequently instructed to complete the Spanish-language version of the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). The SDSC was validated by Bruni et al. in 1996; with a sensitivity of 0.89 and specificity of 0.74, it was designed to detect sleep problems in general. It gathers data on sleep over the last 6 months, and includes 26 items on disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, sleep breathing disorders, disorders of arousal, sleep-wake transition disorders, disorders of excessive somnolence, and sleep hyperhidrosis. We also analysed patients’ clinical characteristics and performed a comparative analysis.17

Data were analysed using the SPSS statistics software (version 24.0).

ResultsSample characteristicsThe sample included a total of 153 patients, 54% of whom were boys. Mean age was 9.8 years (range, 0–18). In 37.8% of patients, epilepsy had presented in the first 2 years of life, and 35% had presented seizures in the last year. EEG studies revealed generalised epileptiform discharges in 50% of patients, and focal discharges in 46%. Focal seizures were the most frequent seizure type (40%), followed by generalised seizures (37.5%). Epilepsy was refractory in 36% of patients, and 43.1% presented epileptic encephalopathy. A total of 53.6% of patients had presented seizures during sleep. Approximately half of the sample (51.6%) had intellectual disability, with 11.1% presenting cerebral palsy (CP).

Characteristics of sleep disorders and sleep hygieneAround 45% of patients had previously consulted due to sleep problems, and 40% had at some point received treatment (melatonin in most cases).

Regarding sleep hygiene, 83% of patients went to bed at the same time every day. A total of 30.7% of patients slept in the same room as their parents (room-sharing), and 23.5% in the same bed (co-sleeping). Thirty-nine percent of patients required parental presence to fall asleep, and 16.3% fell asleep while using such electronic devices as tablets or smartphones. A total of 16.3% of patients frequently refused to go to bed, while 17.6% only occasionally did so. Only 6.5% of the families used nocturnal seizure detection devices, with the most frequent being infrared cameras.

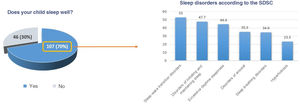

According to overall SDSC results, 84% of patients presented some type of sleep alteration. The most frequent types of sleep alterations were sleep-wake transition disorders (53%), disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (47.7%), and disorders of excessive somnolence (44.4%). Less frequent disorders were sleep breathing disorders (34.6%), disorders of arousal (35.3%), and sleep hyperhidrosis (23.5%) (Fig. 2).

Thirty percent of parents reported that their child slept poorly. Among the group of children whose parents reported that they slept well (70%), a large percentage (75.7%) presented sleep alterations according to the SDSC: 46.7% had sleep-wake transition disorders, 38.3% presented excessive somnolence, 36.5% presented disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, 32% presented sleep breathing disorders, and 30% presented disorders of arousal.

Sleep disorders were more frequent among children with poor sleep hygiene. More specifically, children who relied on their parents’ presence to fall asleep presented more sleep-wake transition disorders (68% vs 42%; P = .019), difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep (68% vs 24%; P = .001), and sleep breathing disorders (48% vs 27%; P = .040) than those falling asleep independently.

Children sleeping in the same room as their parents more frequently presented disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (64%; P = .050) and sleep-wake transition disorders (71.4%; P = .039) than those sleeping in their own room.

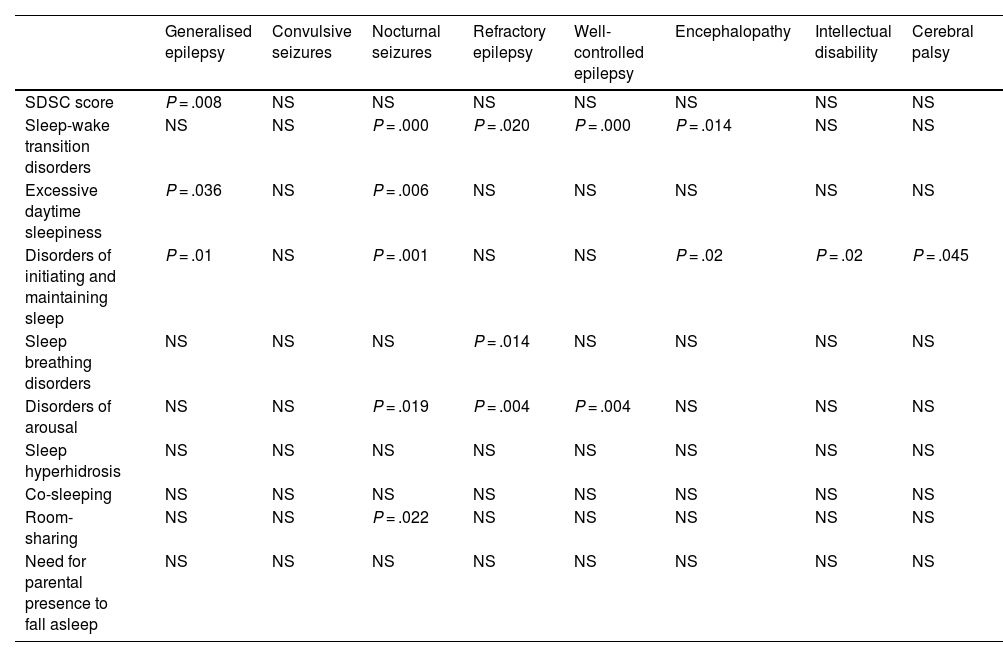

Analysis of clinical characteristics linked to presence of sleep disordersPatients presenting seizures during sleep more frequently presented disorders of excessive somnolence (56% vs 33%; P = .006), disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (59% vs 32%; P = .001), disorders of arousal (40% vs 26%; P = .019), and sleep-wake transition disorders (68.3% vs 33%; P = .001) than those presenting seizures during wakefulness only.

Similarly, patients with generalised epilepsy scored significantly higher overall (6% vs 2%; P = .008) and more frequently presented disorders of excessive somnolence (54% vs 38%; P = .036) and sleep-wake transition disorders (58% vs 32%; P = .001) than those with focal epilepsy.

Patients with refractory epilepsy more frequently presented sleep-wake transition disorders than those without refractory epilepsy (65% vs 46%; P = .020). Patients with epileptic encephalopathy presented a higher frequency of sleep-wake transition disorders (65% vs 45%; P = .014) and disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (59% vs 40%; P = .020) than those without epileptic encephalopathy.

Furthermore, patients with intellectual disability more frequently presented disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep than those without intellectual disability (57% vs 38%; P = .022) (Table 1).

Association between epilepsy characteristics and SDSC scores and sleep hygiene.

| Generalised epilepsy | Convulsive seizures | Nocturnal seizures | Refractory epilepsy | Well-controlled epilepsy | Encephalopathy | Intellectual disability | Cerebral palsy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDSC score | P = .008 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Sleep-wake transition disorders | NS | NS | P = .000 | P = .020 | P = .000 | P = .014 | NS | NS |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | P = .036 | NS | P = .006 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep | P = .01 | NS | P = .001 | NS | NS | P = .02 | P = .02 | P = .045 |

| Sleep breathing disorders | NS | NS | NS | P = .014 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Disorders of arousal | NS | NS | P = .019 | P = .004 | P = .004 | NS | NS | NS |

| Sleep hyperhidrosis | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Co-sleeping | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Room-sharing | NS | NS | P = .022 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Need for parental presence to fall asleep | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

NS: not significant; SDSC: Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children.

Only the presence of nocturnal seizures was associated with poor sleep hygiene (room-sharing) (39%; P = .022). The remaining clinical characteristics of epilepsy (good seizure control in the previous year, seizure type, epilepsy type, presence of refractory epilepsy or epileptic encephalopathy, presence of intellectual disability or CP) showed no association with poor sleep hygiene.

ConclusionsSleep disorders are frequent in patients with epilepsy. While these disorders are twice as frequent in adult patients with epilepsy than in the general population, their prevalence among paediatric patients seems to be higher.18 In fact, children with epilepsy present a wide range of sleep disorders, including insomnia (13.1%–31.5%), excessive daytime sleepiness (10%–47%), parasomnias (52%), and sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome (10%–20%).19,20

In our sample, the prevalence of sleep disorders was even higher than the rates reported in the literature. According to the SDSC, 84% of our patients presented some type of sleep alteration, ranging from sleep-wake transition disorders (53%) to disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (47.7%) and excessive daytime sleepiness (44.4%), all of which were present in nearly half of the population. This higher incidence of sleep disorders in our patients may be due to the high percentage of cases of severe epilepsy, with refractory epilepsy in 36% of cases and epileptic encephalopathy in 43.1%.

In our sample, some clinical characteristics of epilepsy were found to be associated with greater risk of presenting sleep disorders. Presence of intellectual disability was found to be a risk factor for insomnia; this was also observed in previous studies.21

In addition to well-known risk factors for sleep disorders, we also observed the following independent risk factors in our sample: generalised epilepsy, poor seizure control in the previous 12 months, refractory epilepsy, and nocturnal seizures. Children with these types of epilepsy should undergo more comprehensive examination to rule out sleep disorders.

Our results also underscore the need to reconsider the ways in which clinicians gather data on sleep history in children with epilepsy. During the consultation with the paediatric neurologist, asking a single question (“Does your child sleep well?”) about the child’s sleep hygiene is of little help in the screening of sleep disorders, and may result in underdiagnosis. In fact, in our study, the patients who were reported to sleep well presented sleep-wake transition disorders in 46.7% of cases, disorders of excessive somnolence in 38.3%, disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep in 36.5%, sleep breathing disorders in 32%, and disorders of arousal in 30%. Therefore, history taking should seek to gather information on sleep through the use of specific, validated tools, such as the SDSC, or by asking several questions about sleeping patterns, sleep latency, wake-up time on weekdays and on weekends, sleep hygiene (whether the patient falls asleep independently or needs their parents or electronic devices), and presence of sleep-related disorders, such as SAHS and restless legs syndrome.

Another important aspect is the high prevalence of poor sleep hygiene among children with epilepsy. In a study including 111 toddlers and preschool children with epilepsy, 27.8% presented poor sleep hygiene, especially inconsistent bedtimes.22 Another study including 102 school-aged children with epilepsy found higher rates of room-sharing and co-sleeping.23

Few studies have analysed sleep hygiene, despite the impact of this factor on sleep quality; ours is one of the largest studies into sleep hygiene in paediatric patients with epilepsy. As observed in our study, poor sleep hygiene increases the risk of presenting sleep disorders. In fact, recent studies have shown that good sleep hygiene and optimisation of sleep hygiene through educational interventions for families improve sleep, school performance, and behaviour, which in turn improves patient quality of life.15 In our sample, although few patients presented inconsistent bedtimes, a large percentage showed poor sleep hygiene associated with behavioural insomnia, such as requiring parental presence to fall asleep (39%), co-sleeping (23.5%), and room-sharing (30.7%). Behavioural insomnia seems to be associated with parents’ fear that their child will have a seizure during sleep and that it will go unnoticed. In fact, the children more frequently presenting nocturnal seizures slept in their parents’ room. However, the remaining variables analysed were not associated with poorer sleep hygiene: even older children with benign, well-controlled epilepsy presented poorer sleep hygiene. Poor sleep hygiene is therefore not associated with the characteristics of epilepsy, which underscores the value of educating families about the importance of good sleep hygiene.

The main limitations of our study are its lack of a longitudinal design and the fact that we were unable to objectively measure sleep with actigraphy or polysomnography studies.

In conclusion, sleep disorders are frequent in children with epilepsy. Behavioural insomnia associated with poor sleep hygiene is also frequent in these patients, regardless of epilepsy type or severity. Diagnosing, preventing, and actively treating sleep disorders and poor sleep hygiene in children with epilepsy is essential to improving these patients’ and their families’ quality of life, as well as epilepsy prognosis.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.