We present the case of a 44-year-old man with history of primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (homozygous carrier of the Ala91Val mutation) and splenectomy. He presented a 2-month history of sudden-onset, progressive numbness and tingling in the soles of the feet, leg rigidity triggered by physical activity, and gait instability. In addition to these symptoms, the patient had developed numbness and tingling in the palms of both hands 48hours before coming to hospital. He had no epidemiological history of interest.

The physical examination revealed diffuse exaggeration of stretch reflexes, with sustained ankle clonus, bilateral Babinski sign, and spasticity; tactile hypoaesthesia and hypalgesia in the soles of the feet; right leg dysmetria on the heel-to-knee test; and ataxic gait, with positive Romberg sign.

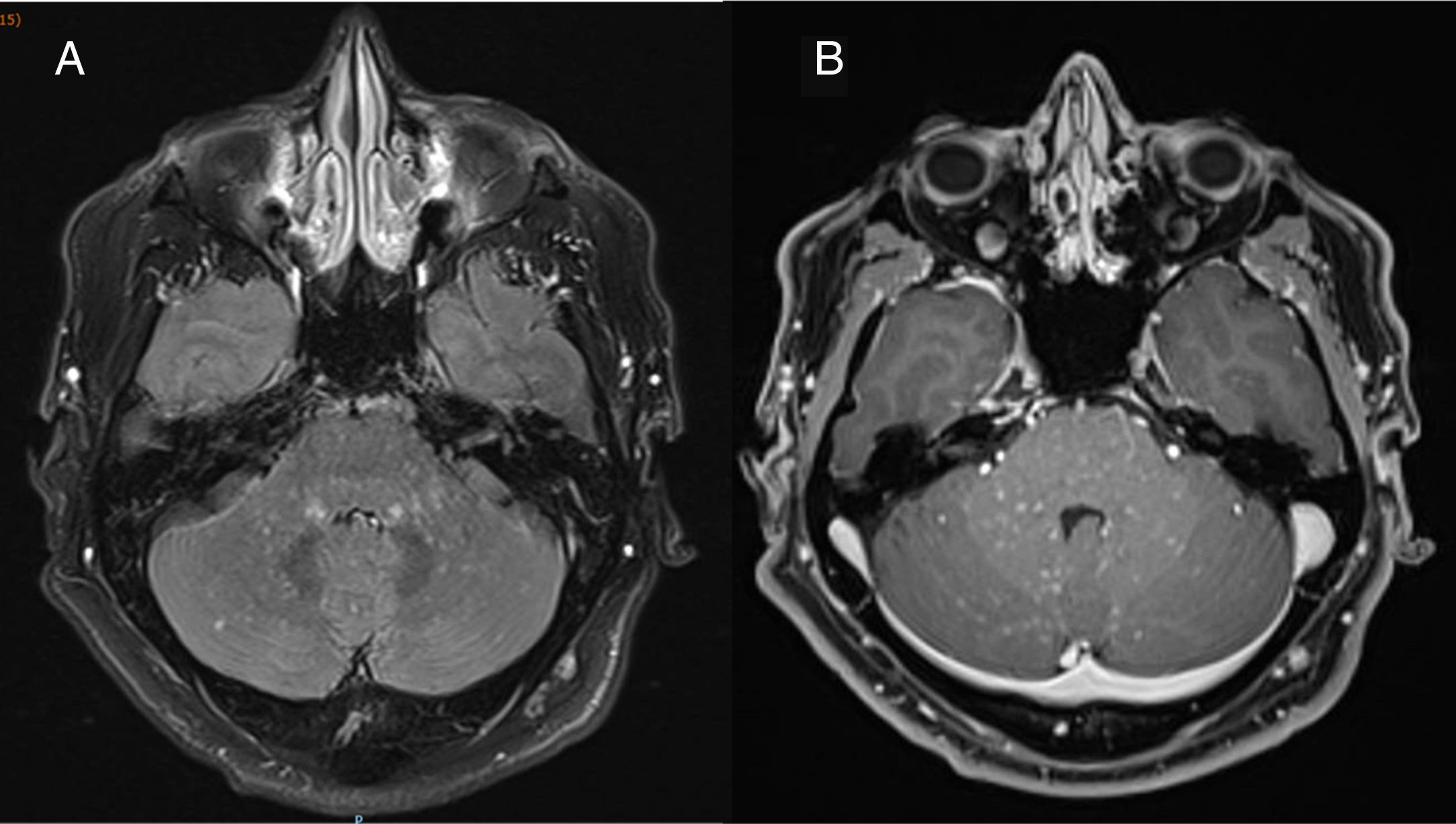

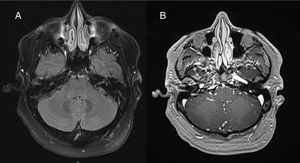

A neurophysiological study including electromyography, nerve conduction studies, and cortical stimulation revealed prolonged motor nerve conduction latencies in the lower limbs, predominantly in the right leg. A brain and spinal cord T2-weighted FLAIR MRI scan (Fig. 1) revealed numerous punctiform hyperintense foci, particularly in the middle cerebellar peduncles, pons, and corticospinal tracts, predominantly on the left side; the lesions showed paramagnetic contrast uptake.

Axial T2-weighted FLAIR brain MRI scan obtained in a 3T scanner at the time of diagnosis, before treatment onset. A) The image shows numerous hyperintense punctiform foci measuring < 3mm in diameter (“salt and pepper sign”), predominantly in the infratentorial region (particularly affecting the middle cerebellar peduncles and pons), with no perilesional mass effect. B) Homogeneous gadolinium enhancement in all punctiform foci.

A blood test yielded normal results; serology tests were negative for HIV, syphilis, Borrelia, Brucella, HTLV-1, cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus family, and hepatitis B and C viruses; and an autoimmunity study revealed no alterations. A CSF analysis revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis, associated with high levels of CD4 + T cells, and high protein levels; no tumour cells or signs of CNS infection were detected. CSF and serum results were negative for onconeuronal and antineutrophil antibodies. A whole-body PET scan was conducted to rule out lymphomatous, inflammatory, systemic, or tumoural diseases.

Given the recent fluctuation of neurological symptoms, we started treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 5 days, followed by decreasing doses of oral prednisone, starting at 1 mg/kg/day. Weakness and rigidity improved and gait instability resolved 72 hours after treatment onset.

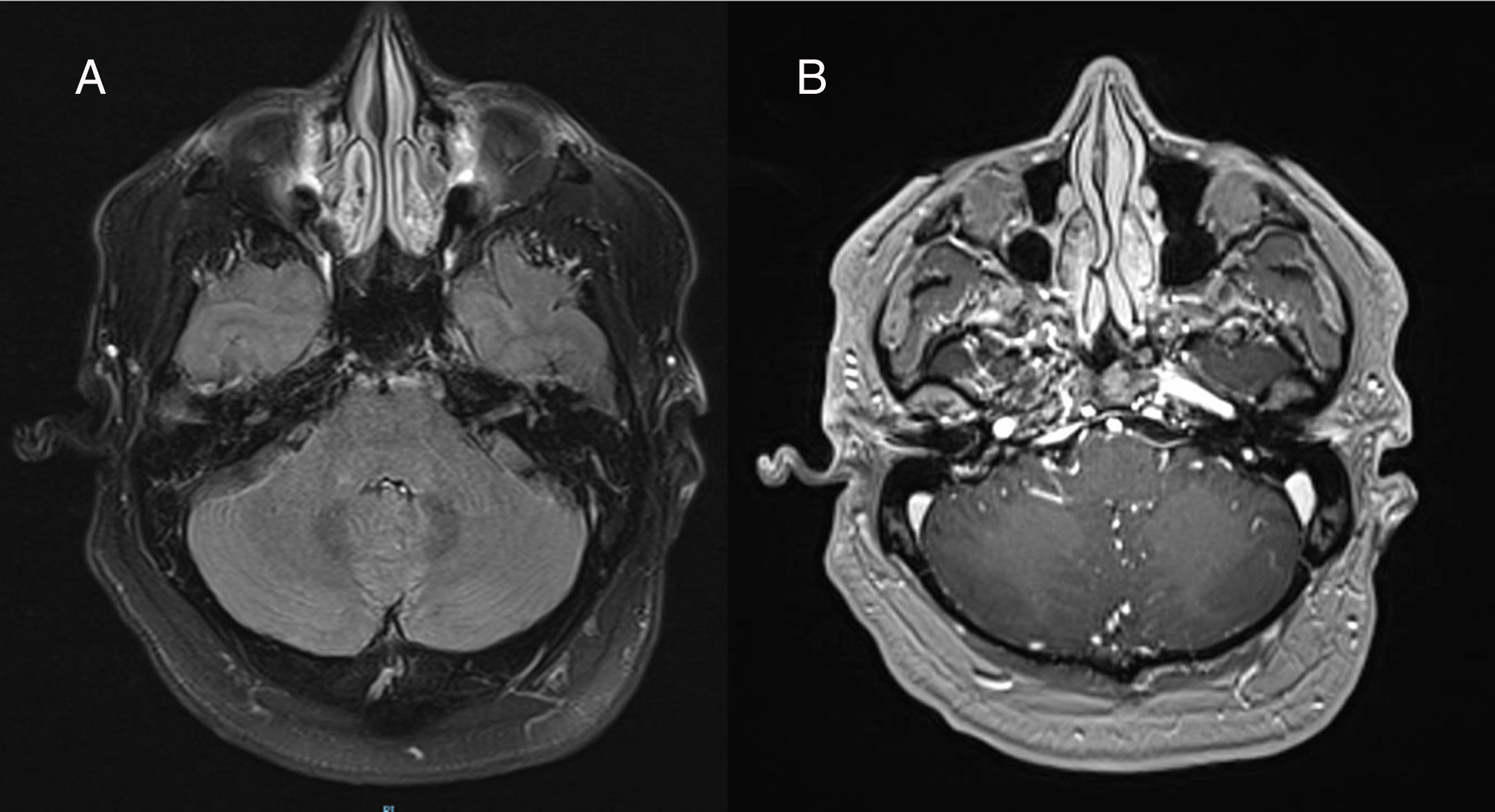

The patient returned to our centre for a follow-up consultation one month later; prednisone dose at that time was 0.5 mg/kg/day. In a follow-up brain and spinal cord MRI study, T2-weighted FLAIR sequences revealed the disappearance of all punctiform hyperintensities; furthermore, no gadolinium-enhancing lesions were observed (Fig. 2).

Axial T2-weighted FLAIR brain MRI scan obtained in a 3T scanner a month after onset of corticosteroid treatment with decreasing doses of prednisone, starting at 1 mg/kg/day. A) Complete disappearance of hyperintense lesions. B) No pathological lesions were observed after intravenous contrast administration.

Having ruled out other systemic diseases, the patient was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS syndrome).

CLIPPERS syndrome is an entity of unknown aetiology, first described by Pittock et al.1 in 2010; approximately 60 cases have since been described worldwide.2,3 Its incidence is unknown. The syndrome predominantly affects men, and is most common in patients with a median age of 50 years.2

From a clinical viewpoint, CLIPPERS syndrome can present with a wide range of symptoms, although the most frequent are diplopia, ataxic gait, and spasticity.4 Differential diagnosis includes a wide range of diseases; laboratory analysis reveals high CSF protein levels and lymphocytic pleocytosis with high levels of CD4 + T cells.1

The diagnostic criteria for CLIPPERS syndrome include subacute neurological symptoms, clinical signs of brainstem involvement, and characteristic radiological images. Brain MRI typically reveals punctiform hyperintensities (<3 mm in diameter) on T2-weighted FLAIR sequences (“salt and pepper sign”), which show gadolinium uptake, with no perilesional mass effect; the lesions appear bilaterally in the pons, cerebellum, and less frequently the spinal cord.5 Diagnostic criteria include complete radiological resolution after high-dose corticosteroid therapy and absence of an alternative diagnosis.1,5 Biopsy of CNS tissue is indicated only in case of atypical findings. In these cases, anatomical pathology studies show perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, predominantly of CD4 + T cells.1

The pathogenic mechanisms of CLIPPERS syndrome remain unknown; it has been hypothesised that the condition may be an inflammatory response to other disease, is of autoimmune origin, or constitutes a variant of lymphoma.

The syndrome usually responds rapidly to corticosteroid therapy. An appropriate treatment schedule is methylprednisolone boluses dosed at 1g/day for 3-5 days, followed by prednisone dosed at 1mg/kg/day, with slowly decreasing doses; the optimal duration of treatment is not well established.1,5,6 According to the literature, patients may present recurrences after the dose of prednisone falls below 20 mg/day.5,6 Starting corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy during corticosteroid discontinuation is essential to prevent relapses that may exacerbate the disease, increasing the level of disability.1,5,7 Non-randomised clinical trials of patients with CLIPPERS syndrome report complete response to maintenance therapy with methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide, with no disease progression5; randomised trials should be conducted to compare the efficacy of these treatments.

Patients presenting clinical or radiological recurrence despite immunosuppressive therapy should undergo thorough examination to rule out an alternative diagnosis.5,7

Please cite this article as: Esparragosa Vázquez I, Valentí-Azcárate R, Gállego Pérez-Larraya J, Riverol Fernández M. Síndrome CLIPPERS. A propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2020;35:690–692.