Bacterial meningitis is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Some of the main pathogens that can cause the disease include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae in the general population; and Streptococcus agalactiae and Listeria monocytogenes in neonates and immunosuppressed individuals, respectively. The recommended empirical treatment for community-acquired bacterial meningitis is a combination of cephalosporins and vancomycin, which may also be combined with another beta-lactam antibiotic.1,2Streptococcus salivarius meningitis is infrequent in our setting, and is mainly associated with spinal procedures.3

We present the case of a 54-year-old woman with no relevant medical or surgical history who visited the emergency department due to sudden-onset holocranial headache of 6 hours' progression, fever (38.5 °C), nausea, and vomiting. She also reported a 4-month history of “sweet tears” associated with right rhinorrhoea triggered by anterior flexion of the neck in both seated and standing positions; this may be attributable to decreased venous return and the transient increase in intracranial pressure. The physical examination revealed general discomfort, blood pressure of 158/89 mm Hg, heart rate of 106 bpm, room-air oxygen saturation of 95%, and rhythmic breathing with normal breath sounds. The neurological examination revealed somnolence (Glasgow Coma Scale: motor 6, verbal 4, eye 3). A head CT scan revealed no abnormal findings. Lumbar puncture revealed purulent CSF; opening pressure could not be measured. A CSF analysis showed 5360 leukocytes/µL (normal range: <5), 74% polymorphonuclear; a protein level of 173 mg/dL (normal range: <30); and a glucose level of 60 mg/dL (normal range: 40-70). A blood analysis revealed a serum glucose level of 154 mg/dL. The patient was diagnosed with bacterial meningitis.

We started intravenous empirical treatment with ceftriaxone 2 g every 12 hours, vancomycin 1 g every 12 hours, ampicillin 2 g every 4 hours, and a single dose of dexamethasone 4 mg. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of 16S rRNA genes in CSF yielded negative results for S. pneumoniae, L. monocytogenes, and N. meningitidis and positive results for S. salivarius, which is susceptible to cephalosporins. Blood culture findings (1:3) 48 h later were positive for S. salivarius.

A biochemical study of nasal discharge revealed a glucose level of 51 mg/dL, 17 leukocytes/µL, and a protein level of 89 mg/dL.

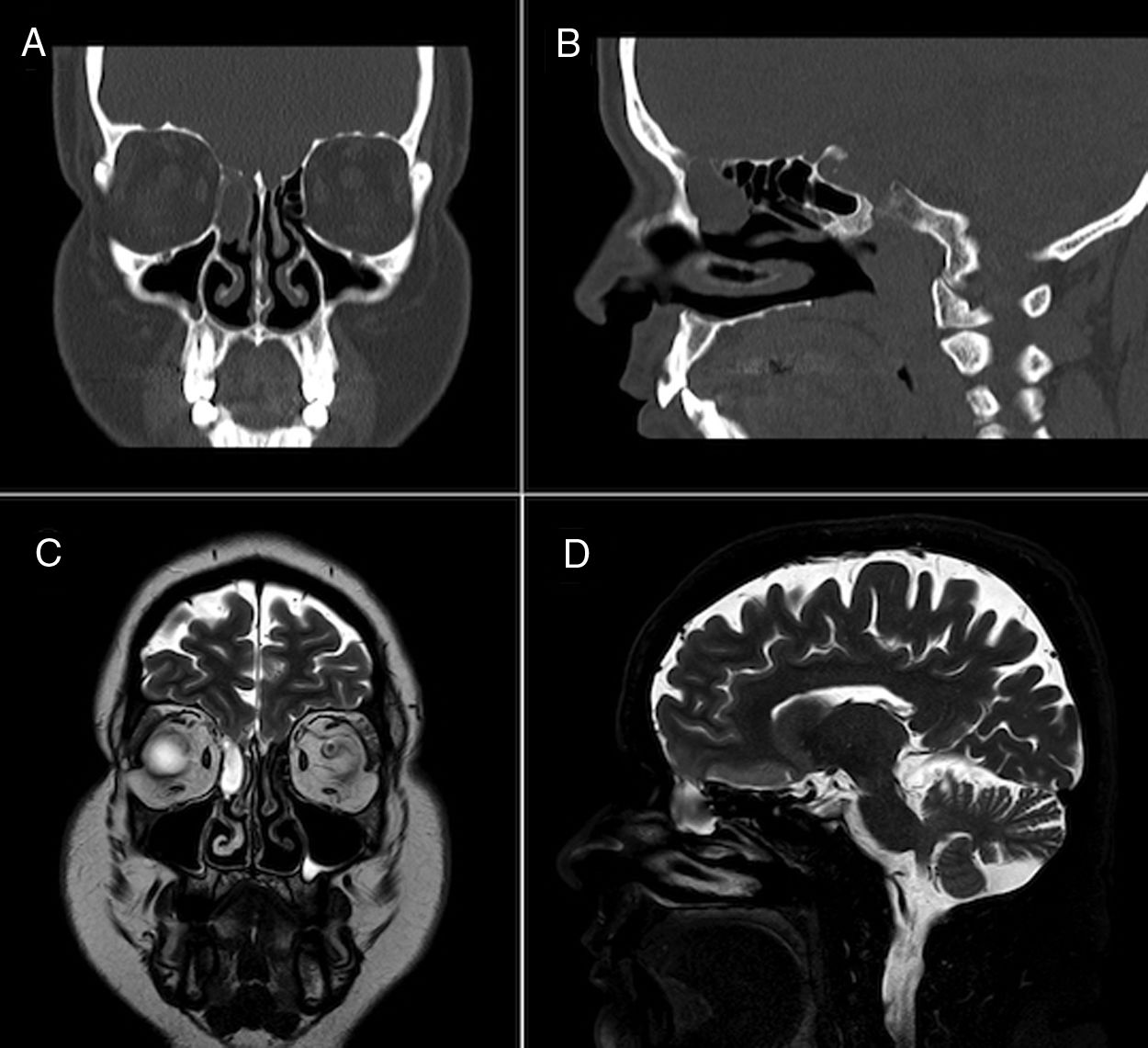

Face CT (Fig. 1A and B) and brain MRI scans (Fig. 1C and D) revealed mucocele in the right ethmoidal air cells measuring 2 cm axially, and a 4-mm defect in the ipsilateral cribriform plate, related with the dural fistula, with MRI detecting no signs of myelomeningocele. The patient continued on ceftriaxone 2 g every 24 hours for 14 days, remaining asymptomatic at discharge. Two months later, the patient underwent surgical excision of the mucocele and endoscopic repair of the CSF fistula on an outpatient basis. After 2 years of follow-up, the patient remains asymptomatic and has presented no further episodes.

S. salivarius, which belongs to the viridans group of streptococci, is a commensal bacterium found in the orogastrointestinal and upper respiratory tracts. Despite its low virulence, it has been associated with bacteraemia, sinusitis, meningitis (approximately 0.3%-2.4% of cases), and endocarditis. Factors potentially favouring the development of S. salivarius meningitis include presence of CSF fistulas, sinusitis, brain abscesses, head trauma, and neoplasia.3–5

Diagnosis is made by isolating the pathogen in CSF cultures or by PCR. Cross-reaction with other Streptococcus species (S. pneumoniae) has been reported, which may result in aetiological misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of the condition.6 The genus Streptococcus presents adequate sensitivity to beta-lactams.

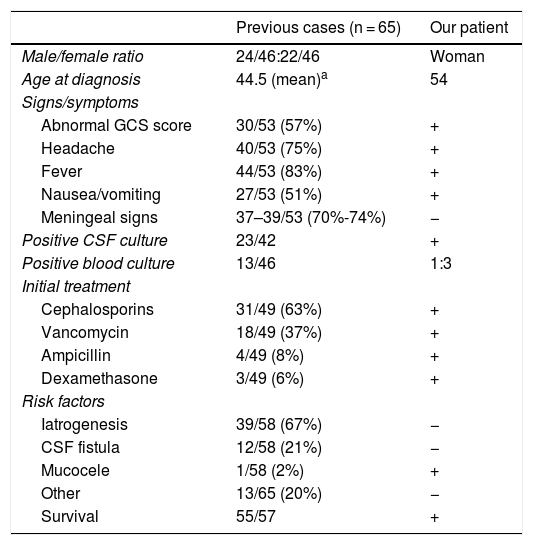

Although bacterial meningitis is a rare complication of spinal procedures (eg, lumbar puncture), it may have a fatal outcome.7 In recent years, several cases have been reported of bacterial meningitis following spinal procedures. The most frequently identified pathogens were oral commensals (viridans group streptococci), which suggests the possibility of direct transmission by physicians through droplets if masks are not used during the procedure.8–10 The literature includes only one case of S. salivarius meningitis secondary to sphenoid sinus mucocele,5 resembling our own. Table 1 compares the clinical characteristics of previous cases of S. salivarius meningitis to the case presented here.

Clinical characteristics of previously reported cases of Streptococcus salivarius meningitis and of our own.

| Previous cases (n = 65) | Our patient | |

|---|---|---|

| Male/female ratio | 24/46:22/46 | Woman |

| Age at diagnosis | 44.5 (mean)a | 54 |

| Signs/symptoms | ||

| Abnormal GCS score | 30/53 (57%) | + |

| Headache | 40/53 (75%) | + |

| Fever | 44/53 (83%) | + |

| Nausea/vomiting | 27/53 (51%) | + |

| Meningeal signs | 37–39/53 (70%-74%) | − |

| Positive CSF culture | 23/42 | + |

| Positive blood culture | 13/46 | 1:3 |

| Initial treatment | ||

| Cephalosporins | 31/49 (63%) | + |

| Vancomycin | 18/49 (37%) | + |

| Ampicillin | 4/49 (8%) | + |

| Dexamethasone | 3/49 (6%) | + |

| Risk factors | ||

| Iatrogenesis | 39/58 (67%) | − |

| CSF fistula | 12/58 (21%) | − |

| Mucocele | 1/58 (2%) | + |

| Other | 13/65 (20%) | − |

| Survival | 55/57 | + |

CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale.

+: present; −: absent.

Source: taken from Wilson et al.3

In conclusion, mucocele or CSF fistula should be suspected in patients with S. salivarius meningitis and no history of spinal procedures; neuroimaging studies should be performed in these patients. As spinal procedures constitute the main risk factor for S. salivarius meningitis, we should stress the need for systematic use of face masks during these procedures.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

The authors wish to thank Dr Alejandro del Castillo Rueda for his support.

Please cite this article as: Oblitas CM, Sánchez-Soblechero A, Pulfer MD. «Lágrimas dulces»: meningitis bacteriana por Streptococcus salivarius secundario a mucocele etmoidal. Neurología. 2020;35:687–690.