The prevalence of behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPS) is very high among patients with Alzheimer disease (AD); more than 90% of AD patients will present such symptoms during the course of the disease. These symptoms result in poorer quality of life for both patients and caregivers and increased healthcare costs. BPS are the main factors involved in increases to the caregiver burden, and they often precipitate the admission of patients to residential care centres.

DevelopmentCurrent consensus holds that intervention models combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are the most effective for AD patients. Several studies have shown cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine combined with cognitive intervention therapy (CIT) to be effective for improving patients’ cognitive function and functional capacity for undertaking daily life activities. However, the efficacy of CIT as a treatment for BPS has not yet been clearly established, which limits its use for this purpose in clinical practice. The objective of this review is to gather available evidence on the efficacy of CIT on BPS in patients with AD.

ConclusionsThe results of this review suggest that CIT may have a beneficial effect on BPS in patients with AD and should therefore be considered a treatment option for patients with AD and BPS.

Los síntomas conductuales y psicológicos (SCP) son muy prevalentes en la enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) presentándose en más del 90% de los pacientes a lo largo del curso de la enfermedad. Los SCP disminuyen la calidad de vida, tanto del paciente, como de sus cuidadores, al tiempo que incrementan los costes asistenciales. Son los principales responsables de la carga que experimentan los cuidadores, favoreciendo la institucionalización prematura de los pacientes.

DesarrolloEn la actualidad existe consenso en considerar más eficaces aquellos modelos de intervención que combinan los tratamientos farmacológicos y los no farmacológicos para personas con EA. En varios estudios se ha comprobado la eficacia de los fármacos anticolinesterásicos y de la memantina combinados con terapias de intervención cognitiva (TIC), para mejorar el funcionamiento cognitivo y la capacidad funcional de los pacientes en el desempeño de las actividades de la vida diaria. Sin embargo, la eficacia de las TIC sobre los SCP no está aun claramente establecida, lo que ha limitado su aplicación con esta finalidad en la práctica clínica. El objetivo de esta revisión es el de recoger la información disponible acerca de la eficacia de las TIC en el tratamiento de los SCP en los pacientes con EA.

ConclusionesLos resultados de esta revisión sugieren que las TIC puede tener efectos beneficiosos sobre los SCP de la EA, por lo que debería ser considerada como una opción terapéutica para el abordaje de los mismos.

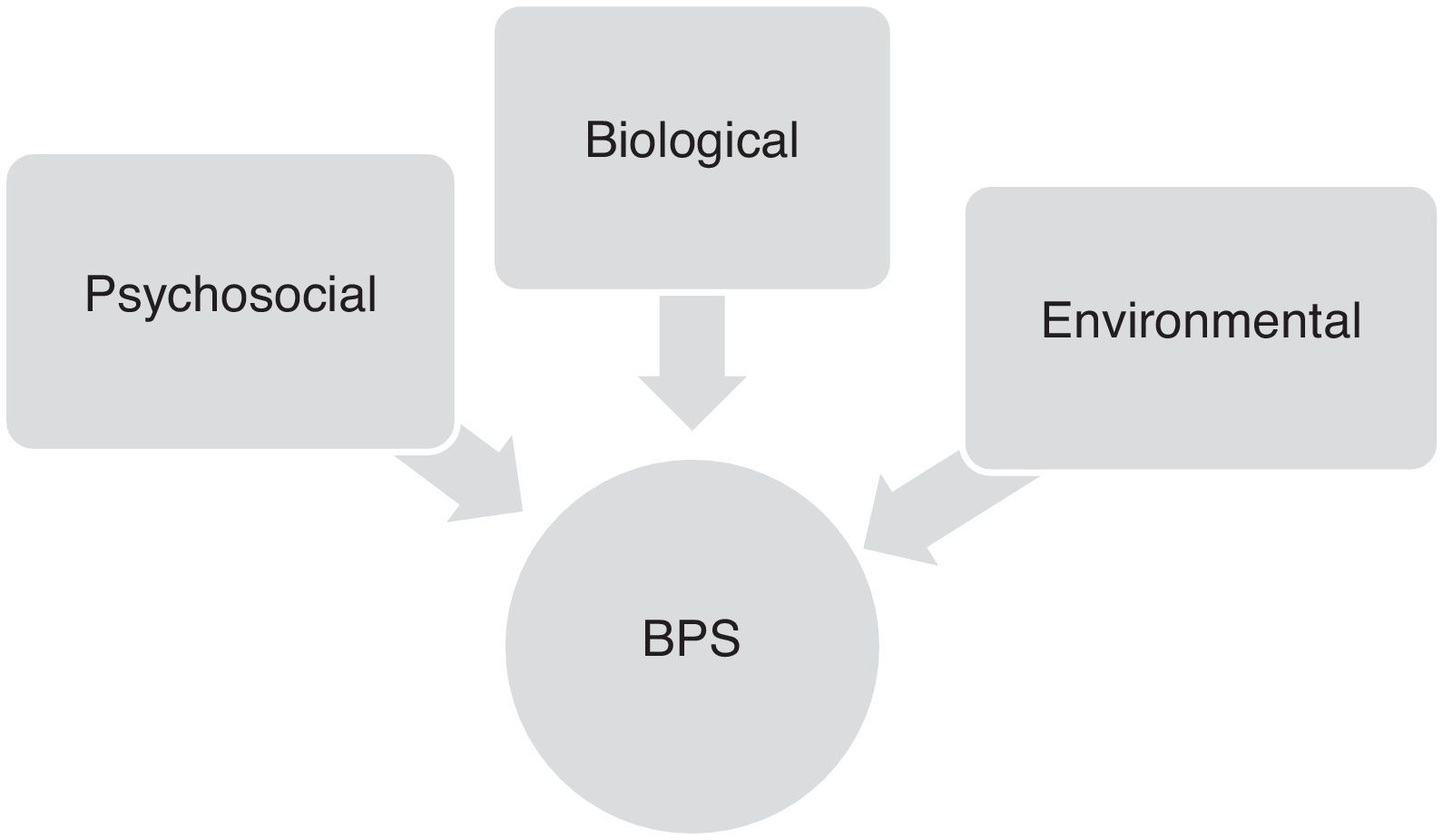

Behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPS) are present in most patients with Alzheimer disease (AD).1 Over the course of the disease, more than 90% of all patients will experience such symptoms as apathy, agitation, anxiety, depression, hallucinations, delusions, abnormal motor activity, irritability, sleep disorders, eating disorders, euphoria, or disinhibition (Table 1).2–4

Behavioural and psychological symptoms in a sample of 125 community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer disease and evaluated using the NPI

| N (%) | Mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Apathy | 92 (74) | 5.30±4.27 |

| Irritability | 82 (66) | 3.18±3.05 |

| Depression | 75 (60) | 3.84±3.54 |

| Agitation | 69 (55) | 2.86±3.21 |

| Anxiety | 67 (54) | 2.70±3.23 |

| Abnormal motor behaviour | 59 (47) | 3.71±4.87 |

| Delusions | 47 (38) | 1.73±2.97 |

| Sleep disorders | 45 (36) | 1.78±2.91 |

| Disinhibition | 37 (30) | 0.78±1.65 |

| Appetite | 35 (28) | 1.30±2.39 |

| Hallucinations | 25 (20) | 0.72±1.95 |

| Euphoria | 5 (4) | 0.14±1.10 |

SD: standard deviation; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; BPS: behavioural and psychological symptoms.

These BPS significantly decrease quality of life in patients and family members/caregivers alike,5 and cause considerable suffering for both groups.6,7 This situation favours the early placement of AD patients in institutions.8,9 Presence of BPS is associated with increased consumption of psychoactive drugs, increased healthcare costs,10 and the use of physical restraints.11 Furthermore, caregivers report needing more help on a daily basis in order to perform household tasks and supervise and provide personal care for the patient with BPS.12 In turn, this means that caregivers must adapt their lifestyles more drastically13 and are left with less time for themselves.14 Epidemiological studies show that rates of psychiatric diagnosis, especially anxiety and depression, are systematically higher in relatives caring for AD patients than in the general population.15

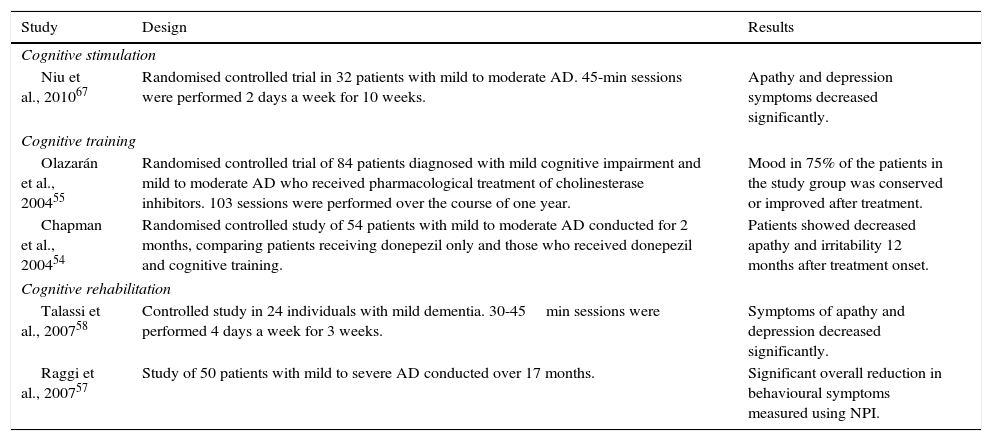

Factors contributing to onset of behavioural and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer diseaseOnset and progression of BPS in AD patients are the result of complex interactions between neurobiological, psychosocial, and environmental factors. Although these symptoms vary greatly from patient to patient, their frequency and severity tend to increase gradually as cognitive and functional impairment progresses (Fig. 1).16

Neurobiological factorsAlthough studies on this topic are relatively scarce, BPS have been associated with the underlying neurobiological changes in the brains of AD patients. Apathy in AD has been associated with dysfunction in the areas that make up the frontal-subcortical circuits, which is evidenced by hypoperfusion and hypometabolism in the anterior cingulate gyrus (ACG),17,18 orbitofrontal cortex (OFC),19 and in the nucleus basalis of Meynert and the hippocampus. Apathy has also been correlated to neuronal loss and higher density of neurofibrillary tangles in the same regions.

Depression is associated with dysfunction of frontal-subcortical and subcortical limbic circuits (locus coeruleus, substantia nigra, hippocampus, and hypothalamus), evidenced by hypoperfusion in the ACG and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPC),19–21 and also with frontal and prefrontal hypometabolism.19,20 Likewise, some lines of research suggest that dysfunction of the frontal cortex or orbitofrontal-subcortical circuits play a fundamental role in the onset of agitation and disinhibition.22

In turn, psychotic symptoms have been associated with an increased number of neurofibrillary tangles in the neocortex,23 while agitation has been linked to increased deposition of neurofibrillary tangles in the OFC.22

Additionally, some studies have found genetic associations for some types of BPS in AD. For example, researchers have described an association between the ¿4 allele of the apolipoprotein E and the presence of delusions and agitation,24 as well as a link between depression in AD and personal history of depression.25 It has also been suggested that some types of BPS may be linked to changes occurring in the neurotransmission systems affected in AD, especially those that involve glutamate, acetylcholine, serotonin, noradrenaline, or dopamine. Dysfunction in these systems may be related to changes in mood (serotonin and noradrenaline), movement disorders (dopamine), aggressive behaviour (serotonin) and apathy (acetylcholine).26–28

Psychosocial and environmental factorsVarious psychosocial models, in the broadest sense of the term, may help explain the origin and persistence of the behavioural changes observed in AD in a significant number of cases.

The unmet needs model29 proposes that BPS could be the result of unmet physical, social, or emotional needs due to the patient's difficulty expressing them and the caregiver's difficulty identifying or addressing them. These needs may include hunger, thirst, pain, abandonment, and fear. Patients with unmet needs might consequently react to adverse events by adopting disruptive behaviours that can be stressful for patients themselves and for those around them. For example, shouting and insults might indicate an attempt to communicate a need or express pain or discomfort due to an underlying medical problem.

The progressively lowered stress threshold model30 suggests that dementia progressively lowers the threshold for tolerating stress or unpleasant stimuli. Once this threshold is exceeded, the patient will adopt disruptive or inappropriate behaviours. For example, catastrophic reactions can be triggered by such frustrating experiences as not being able to manage money or to choose which clothes to wear.

Thirdly, the learning model31,32 assumes that certain environmental stimuli trigger behaviours that patients learn to continue or repress, depending on the positive or negative consequences of those behaviours. For example, a shouting patient may receive the caregiver's undivided attention, but be ignored when calm. This would therefore inadvertently provide a reward for shouting and not for remaining calm.

Lastly, environmental factors such as excessive noise, insufficient lighting, lack of daily routines, excessive demands, or stress-inducing behaviours of other parties can also trigger some types of BPS.33

In light of the above, and considering that AD is still incurable despite advances in treatment, it is vital to delay disease progression and its negative consequences on people with AD.34 This will also alleviate the burden and suffering of their relatives and caregivers. Current consensus is that intervention models that combine pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment are the most effective for patients with AD.33,35

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have been approved for treating patients with AD. The clinical trials conducted to determine their efficacy have shown that they are useful for improving the cognitive performance and functional capacity of patients with this disease.36,37 Furthermore, some studies also report that they effectively reduce the frequency and severity of BPS.6,38,39 Additionally, among non-pharmacological approaches, CITs including cognitive training, cognitive rehabilitation, and cognitive stimulation, have been able to stabilise or improve cognitive performance and the performance of activities of daily life in patients with mild or moderate AD.40–43 However, their efficacy for treating BPS remains unclear, which limits their use for this indication in clinical practice.44 Cognitive stimulation therapy programmes essentially consist of interventions for patients with mild or moderate AD, usually in groups. Session duration varies and activities include short-term and long-term memory enhancement tasks, sensory stimulation, reality orientation, etc. Programmes of this type are currently complemented by physical exercise, music therapy, and different types of games; this array of activities is called enhanced cognitive stimulation. In contrast, cognitive training programmes provide a more personalised way of developing strategies and specific cognitive abilities, and they may be conducted in individual or group sessions. They may also include software-based training. Lastly, cognitive rehabilitation therapy includes several types of interventions developed according to the principles of implicit learning. Interventions are designed in a very personalised way and they focus on very specific targets that are relevant for the patient. This type of therapy can also include other members of the patient's family.45

The aim of this review article is to verify existing information about the benefits of CIT for treating BPS in AD patients. Our purpose is to provide a comprehensive view of the topic rather than to focus on results of each study individually.

MethodStudies related to this subject were reviewed in 2 phases. In the first phase we searched for review articles on CIT; in the second phase we searched for research articles exploring the presence of a neurobiological and epidemiological association between CIT and BPS in AD. We used the following electronic databases: Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, and The Cochrane Library. Studies published up to 15 February 2012 were included.

DevelopmentCognitive intervention therapy for improving cognition in Alzheimer diseaseCITs aimed at improving cognitive performance and functional capacity of AD patients involve the guided practice of a set of tasks designed to stimulate or train cognitive functions in a particular way. These functions include memory, attention, and executive capacities; practice sessions can be carried out in various formats and with different procedures.46

In a recent review, Olazarán et al.47 found evidence suggesting that sessions aimed at training and stimulating cognitive abilities, whether presented to individuals or groups, specifically improve the listed cognitive skills. More specifically, group training of specific cognitive abilities improved verbal and visual learning in subjects attending memory training sessions held daily48 or 2 days a week.49 Training in individual sessions directed by the therapist or the patient's own caregiver also resulted in positive effects on cognition.50,51 Similarly, group cognitive stimulation sessions yielded significant improvements in outcome measures related to attention, memory, orientation, language, and overall cognitive performance.52,53 Multicomponent interventions deliver similar results when they include cognitive stimulation as part of a training programme combining reminiscence therapy, physical exercise, training for activities of daily life, and supportive therapy.54–56

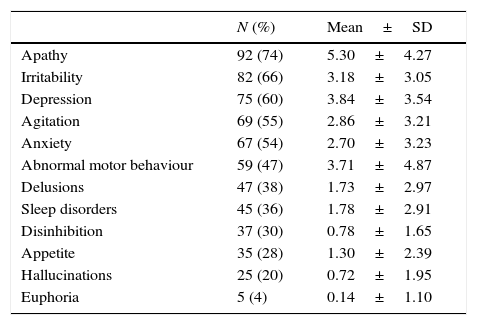

Cognitive intervention therapies for reducing behavioural and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer diseaseSome clinical studies have shown that CIT significantly reduces BPS frequency and severity in AD patients (Table 2). However, the value of these studies is limited due to their small samples sizes,35 or because they did not examine the effects of CIT on specific BPS,57 or with regard to the different stages of dementia.58

Summary of the main studies on the efficacy of CITs for treating BPS in patients with Alzheimer disease

| Study | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive stimulation | ||

| Niu et al., 201067 | Randomised controlled trial in 32 patients with mild to moderate AD. 45-min sessions were performed 2 days a week for 10 weeks. | Apathy and depression symptoms decreased significantly. |

| Cognitive training | ||

| Olazarán et al., 200455 | Randomised controlled trial of 84 patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and mild to moderate AD who received pharmacological treatment of cholinesterase inhibitors. 103 sessions were performed over the course of one year. | Mood in 75% of the patients in the study group was conserved or improved after treatment. |

| Chapman et al., 200454 | Randomised controlled study of 54 patients with mild to moderate AD conducted for 2 months, comparing patients receiving donepezil only and those who received donepezil and cognitive training. | Patients showed decreased apathy and irritability 12 months after treatment onset. |

| Cognitive rehabilitation | ||

| Talassi et al., 200758 | Controlled study in 24 individuals with mild dementia. 30-45min sessions were performed 4 days a week for 3 weeks. | Symptoms of apathy and depression decreased significantly. |

| Raggi et al., 200757 | Study of 50 patients with mild to severe AD conducted over 17 months. | Significant overall reduction in behavioural symptoms measured using NPI. |

AD: Alzheimer disease; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; BPS: behavioural and psychological symptoms; CIT: cognitive intervention therapy.

In the systematic review by Olazarán et al.47 that we mentioned before, the most noticeable effect on behaviour was made apparent by combining results from 3 small randomised controlled trials on cognitive stimulation conducted in institutionalised dementia patients. Researchers measured behavioural problems,59 emotional control,60 and abnormal behaviour.61 Furthermore, multicomponent intervention programmes enriched with group cognitive stimulation delivered moderate improvements in conduct54,62 and social isolation42,63 in non-institutionalised dementia patients.

In an uncontrolled clinical study, 50 patients diagnosed with mild to severe dementia were treated with reality orientation therapy over a period of 17 months.57 The therapy was complemented, when necessary, with individualised cognitive interventions. BPS were evaluated using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).64 Results showed a decrease of 60% in the total NPI score at the end of the treatment programme. Additionally, a 3-week controlled study by Talassi et al.58 compared the efficacies of a cognitive rehabilitation programme (CRP) and a rehabilitation programme not providing stimulation of cognitive functions (NCRP) for patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild dementia. The CRP included 3 types of activities: computer-assisted cognitive training (CAT), occupational therapy (OT), and behavioural training (BT). The programme was aimed at treating affective symptoms using communication strategies and behaviour therapy. BPS were assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale,65 State Trait Anxiety Inventory,66 and NPI. Results showed that both patients with MCI and those with mild dementia treated with CRP presented significantly reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression after the treatment period. On the contrary, this effect was not observed in the patients assigned to the NCRP group.

More recently, a 10-week randomised controlled clinical trial conducted in patients with mild or moderate AD67 showed that completing a cognitive stimulation programme focussing on the activation of executive and memory functions, combined with stable doses of a cholinesterase inhibitor, managed to significantly reduce levels of apathy and depression. Patients who participated in the trial had been taking a stable dose of donepezil for at least 3 months before beginning the cognitive stimulation programme. Since 3 months is the time estimated to reach maximum drug efficacy,68 the authors suggest that the favourable results obtained in the trial cannot be attributed to medication. Likewise, treatment with psychoactive drugs was not modified before or during patients’ participation in the trial so as to limit their possible influence on cognition and BPS. Since all participants resided in the same region in similar settings and circumstances, the authors ruled out an environmental influence on the trial's results.

ConclusionsFor a better understanding of the data described, we should not forget that recent studies have shown a decline in executive functions in patients with AD from the earliest stages of the disease.69–71 These studies have also shown that the same areas involved in the presence of frontal BPS (apathy, depression, agitation, disinhibition), especially the ACG, OFC, and DLPC, play an important role in the performance of such important specific executive functions as inhibitory control, divided attention, and complex thinking skills.72,73

Convergence of these data suggests that some BPS (apathy, depression, agitation, disinhibition) and some executive functions (mainly inhibitory control and divided attention) could share underlying neuroanatomical features in the frontal lobe and frontal-subcortical circuits.18,74–76 Therefore, remission of behavioural symptoms in AD patients who receive CIT may be consistent with this overlap in the affected frontal regions. In fact, apathy is currently considered one of the earliest behavioural symptoms of frontal system dysfunction and it constitutes a type of executive dysfunction that results from neuropathological changes in the frontal regions of the brain.28,77

This hypothesis is supported by several studies showing that increased metabolism and regional cerebral blood flow are linked to the performance of cognitive tasks.77,78 Activation of these cortical regions using CITs may partially improve metabolism and regional cerebral blood flow,77,79 which could in turn lead to improved cognitive performance in these patients. More specifically, CITs may be associated with neurobiological changes in association cortices, and especially those in the frontal lobe region.80 CITs stimulate such cerebral functions as complex attention, working memory, flexibility, self-control, reasoning, and abstract thinking, all of which are important traits in executive performance. CITs would therefore also help improve BPS associated with neural deficits underlying frontal lobe dysfunction.73,81,82

Furthermore, according to aetiological approaches proposed by psychosocial models, and considering that patients maintain some cognitive reserves during mild and moderate stages of the disease, CITs may increase the use of the patient's remaining cognitive and functional capacities. CITs may also help increase patients’ self-confidence and motivation and inspire a new positive attitude towards life, which in turn would decrease disruptive BPS. Additionally, during mild and moderate stages of AD, improvements in cognitive performance and functional capacities delivered by CITs would make it easier for patients to express their wants and needs, which would also increase their threshold for tolerating stress.67,83 Although some studies32,84 have shown social intercourse to be beneficial for reducing BPS, a recent randomised controlled trial67 demonstrated lower levels of apathy and depression in patients treated with a cognitive stimulation programme than in the control group, regardless of any positive effect of social intercourse or attention from patients’ close family and friends.

If we analyse the hypotheses postulated by these models, we observe that BPS in AD are often the result of typical interactions between patients and their family members or caregivers.4,85,86 Based on the above, patients with mild or moderate AD tend to overestimate their cognitive and functional capacities compared to what their family members report. Because of this discrepancy in the way family members and patients themselves assess the patients’ cognitive capacity in AD, patients may feel misunderstood and excluded by their relatives, which could accelerate the appearance of some types of BPS.81,87 In such cases, family members should participate in CIT sessions to better understand the reasons underlying some of the BPS exhibited by the patients they care for, and this approach could help reduce their symptoms.87

In conclusion, this review article shows that both our current knowledge of factors contributing to presence and progression of BPS in AD, and our list of appropriate treatment strategies, are limited. However, our results suggest that CIT programmes have positive effects on the behavioural symptoms of dementia, especially in cases of apathy, anxiety, irritability, and depression. Therefore, CIT programmes should be considered a treatment alternative for managing cognitive and functional impairment and also BPS in patients with mild to moderate AD. The increasing numbers of successful experiences using CIT programmes could improve patients’ self-confidence and psychological well-being, and thus decrease their psychological distress and reduce BPS. These effects would consequently alleviate the carer's burden and suffering, improve quality of life for both parties, and decrease patients’ probability of being institutionalised.

We need further randomised controlled trials to clarify the efficacy of CITs on BPS in AD. Other studies must determine the behavioural domains in which improvements delivered by these non-pharmacological interventions are the most pronounced and the most likely to occur. Future research should also be aimed at maximising our understanding of neurobiological correlations of the neuropsychological and behavioural benefits obtained using CITs, as well as helping develop intervention programmes designed according to each patient's individual needs.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: García-Alberca JM. Las terapias de intervención cognitiva en el tratamiento de los trastornos de conducta en la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Evidencias sobre su eficacia y correlaciones neurobiológicas. Neurología. 2015;30:8–15.