Hemifacial spasm is characterised by chronic, involuntary, paroxysmal contractions of one side of the face. The disorder develops gradually, beginning with the orbicularis oculi muscle and progressively involving muscles of the lower half of the face. Although diagnosis is mainly clinical, we should rule out presence of vascular malformations or tumours at the emergence of the facial nerve (CN VII) from the brainstem using brain MRI and MRI angiography.1 Most cases of hemifacial spasm correspond to primary forms. Compression of the facial nerve root by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery1,2 is the most frequent cause, although other causes have also been described, including compression by veins,3 other anatomical variants,4 and brainstem lesions or arteriovenous malformations. Two different theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon. The peripheral theory proposes that chronic irritation of the facial nerve nucleus or proximal nerve segment causes axon demyelination, resulting in ephaptic transmission of impulses and excessive firing of the facial nerve. The central theory, in contrast, postulates that irritation of peripheral facial nerve fibres induces excessive afferent (antidromic) activity, causing a functional reorganisation of synapses within the facial nucleus that results in abnormal firing of the nucleus.1

Chemodenervation with botulinum toxin is the treatment of choice due to its efficacy and safety profile, although it must be administered periodically and may cause adverse reactions. Botulinum toxin type A (BTA) acts at the neuromuscular junction, inhibiting the release of acetylcholine mediated by calcium channels through its interaction with SNAP25, a protein involved in vesicle fusion and acetylcholine release. This leads to local chemical denervation, causing transient, reversible muscle paralysis. The only definitive treatment, recommended in severe or refractory cases, is microvascular decompression. Oral medication is usually indicated in mild cases, patients unwilling to undergo BTA injection, and patients ineligible for surgery. Several trials have been conducted of anticholinergics, antipsychotics, and such antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) as carbamazepine (CBZ), gapabentin (GBP), and clonazepam, with inconsistent results.1,5

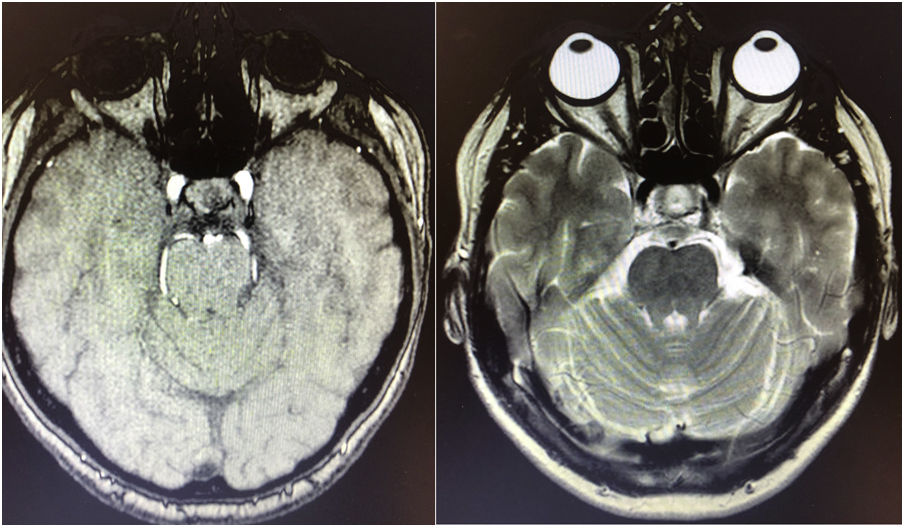

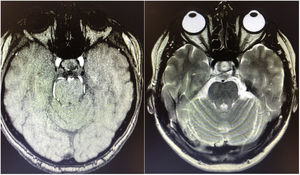

We describe the case of a 68-year-old woman with no relevant medical history who presented short-lived paroxysmal contractions of the left side of the face, involving the left orbicularis oculi, left levator anguli oris, and left mentalis muscles (Fig. 1; Appendix A, Supplementary data). Brain MRI and MRI angiography ruled out secondary causes (Fig. 2). We indicated monotherapy with eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) dosed at 800 mg once daily; after achieving a clinical response, the dose was increased to 1200 mg, which achieved complete symptom resolution with excellent tolerance.

This is the first reported case of hemifacial spasm responding to ESL. The literature includes reports of patients with paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia,6–9 chorea,10 or hemifacial spasm secondary to mucopolysaccharidosis type II successfully treated with CBZ.11 ESL has successfully been used for the treatment of vestibular paroxysmia following failure of GBP.12 ESL is a third-generation AED approved in 2009 by the European Medicines Agency and in 2013 by the United States Food and Drug Administration, and has been available on the Spanish market since February 2011.13 It is currently indicated as monotherapy for focal-onset seizures with or without secondary generalisation in adults with epilepsy, or as adjuvant therapy.13,14

ESL, CBZ, and oxcarbazepine (OXC) all belong to the dibenzazepine family. Interestingly, ESL selectively interacts with the inactive state of voltage-dependent sodium channels through slow inactivation (unlike CBZ and OXC) and inhibits hCaV3.2 inward currents with greater affinity than CBZ. Although these drugs are not indicated for the treatment of neuropathic pain, headache, or neuralgia, they are frequently used off-label in clinical practice. Several studies have reported favourable results in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia, and other cranial neuralgias with ESL,13 with response rates of 88.9% for trigeminal neuralgia. Trigeminal neuralgia is characterised by demyelination of A-δ fibres; it has been hypothesised that paroxysmal attacks result from ectopic afterdischarges in damaged axons, triggered and amplified by ephaptic conduction and cross-excitation transmitted by afferent A-β fibres after trivial sensory stimuli. ESL suppresses ectopic discharges from hyperexcitable fibres by inhibiting voltage-dependent sodium channels in the slow inactivation phase. This theory may be extrapolated to hemifacial spasm, whose pathophysiological mechanism is similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia.15 Pending further research, we believe that ESL may be an effective alternative in the treatment of hemifacial spasm.

Ethics approvalThis study complies with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. It did not require participation of the patient or performance of any invasive tests or techniques. No activity outside normal clinical practice was performed. The patient gave informed consent to use of her likeness and clinical data for research and training purposes.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to thank our patient for consenting to the publication of her clinical case.

Please cite this article as: Marín Gracia M, Gutiérrez Álvarez ÁM. Acetato de eslicarbazepina como terapia en el espasmo hemifacial. Neurología. 2022;37:229–231.