Ischaemic stroke may be a major complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Studying and characterising the different aetiological subtypes, clinical characteristics, and functional outcomes may be valuable in guiding patient selection for optimal management and treatment.

MethodsData were collected retrospectively on consecutive patients with COVID-19 who developed acute focal brain ischaemia (between 1 March and 19 April 2020) at a tertiary university hospital in Madrid (Spain).

ResultsDuring the study period, 1594 patients were diagnosed with COVID-19. We found 22 patients with ischaemic stroke (1.38%), 6 of whom did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 16 patients were included in the study (15 cases of ischaemic stroke and one case of transient ischaemic attack).

Median baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 9 (interquartile range: 16), and mean (standard deviation) age was 73 years (12.8). Twelve patients (75%) were men. Mean time from COVID-19 symptom onset to stroke onset was 13 days. Large vessel occlusion was identified in 12 patients (75%).

We detected elevated levels of D-dimer in 87.5% of patients and C-reactive protein in 81.2%. The main aetiology was atherothrombotic stroke (9 patients, 56.3%), with the predominant subtype being endoluminal thrombus (5 patients, 31.2%), involving the internal carotid artery in 4 cases and the aortic arch in one. The mortality rate in our series was 44% (7 of 16 patients).

ConclusionsIn patients with COVID-19, the most frequent stroke aetiology was atherothrombosis, with a high proportion of endoluminal thrombus (31.2% of patients). Our clinical and laboratory data support COVID-19–associated coagulopathy as a relevant pathophysiological mechanism for ischaemic stroke in these patients.

El ictus isquémico puede ser una complicación grave en los pacientes con infección por SARS-CoV-2.

Estudiar y caracterizar los diferentes subtipos etiológicos, las características clínicas y el pronóstico funcional podrá resultar útil en la selección de pacientes para un manejo y tratamiento óptimos.

MétodosLa recogida de variables se hizo de forma retrospectiva en pacientes consecutivos con infección por COVID-19 que desarrollaron un episodio de isquemia cerebral focal (entre el 1 de Marzo 1, 2020, y el 19 de Abril, 2020). Se llevó a cabo en un hospital universitario de tercer nivel en la Comunidad de Madrid. (España).

ResultadosDurante el período de estudio 1594 pacientes fueron diagnosticados de infección por COVID 19. Identificamos 22 pacientes con ictus isquémico (1.38%), de estos no cumplieron los criterios de inclusión 6. Un total de 16 pacientes con isquemia cerebral focal constituyeron la serie del estudio (15 con ictus isquémico y 1 con accidente isquémico transitorio).

En la valoración basal en el National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) la mediana fue de 9 (Rango Intercuartil RIQ: 16), la edad media fue de 73 años (DE±12.8). 12 pacientes fueros varones (75%). El tiempo desde los síntomas de COVID-19 hasta el ictus fue de 13 días. Se encontró oclusión de gran vaso en 12 pacientes (75%).

El dímero –D estuvo elevado en el 87.5% y la proteína C reactiva en el 81.2% de los casos. La etiología más frecuente del ictus isquémico fue la aterotrombosis (9 pacientes, 56.3%) con un subtipo predominante que fue el trombo endoluminal sobre placa de ateroma (5 pacientes, 31.2%), 4 de ellos en la arteria carótida interna y uno de ellos en el arco aórtico. La mortalidad en nuestra serie fue del 44% (7 de 16 pacientes).

ConclusionesEn los pacientes con ictus y COVID-19 la etiología más frecuente fue la aterotrombótica con una elevada frecuencia de trombo endoluminal sobre placa de ateroma (31.2% de los pacientes). Nuestros hallazgos clínicos y de laboratorio apoyan la coagulopatía asociada a COVID-19 como un mecanismo etiopatogénico relevante en el ictus isquémico en este contexto.

The COVID-19 pandemic has represented a major challenge for stroke care. An association between ischaemic stroke and SARS-CoV-2 infection has been suggested by several authors.1–5

However, our understanding of the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2–related ischaemic stroke is limited due to the lack of anatomoclinical studies and randomised trials. Systematically documenting the clinical characteristics and laboratory and radiological findings from these patients is therefore essential.

The purpose of this study is to analyse a consecutive series of patients with ischaemic stroke and COVID-19, gathering data on:

- 1.

demographic, clinical, laboratory, radiological, and functional prognosis variables; and

- 2.

the aetiological subtype of ischaemic stroke.

We conducted a retrospective, observational study at Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, a tertiary-level university hospital of the region of Madrid (Spain). The study was approved by our hospital’s research ethics committee. We selected consecutive patients attending our centre between 1 March and 19 April 2020. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) radiologically-confirmed ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) scoring > 3 on the ABCD2 scale6; 2) presence of COVID-19 symptoms before stroke onset; and 3) RT-PCR–confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (nasopharyngeal swab).

During the pandemic, a protocol was established for stroke care in patients with COVID-19. These patients were assessed according to the standard procedures of the stroke unit, which included a brain neuroimaging study, intra- and extracranial vascular neuroimaging study, transthoracic echocardiography, and continuous monitoring with electrocardiography and telemetry.

We reviewed the clinical histories of 1594 patients admitted to our centre due to COVID-19 pneumonia in order to determine the frequency of ischaemic stroke in this population.

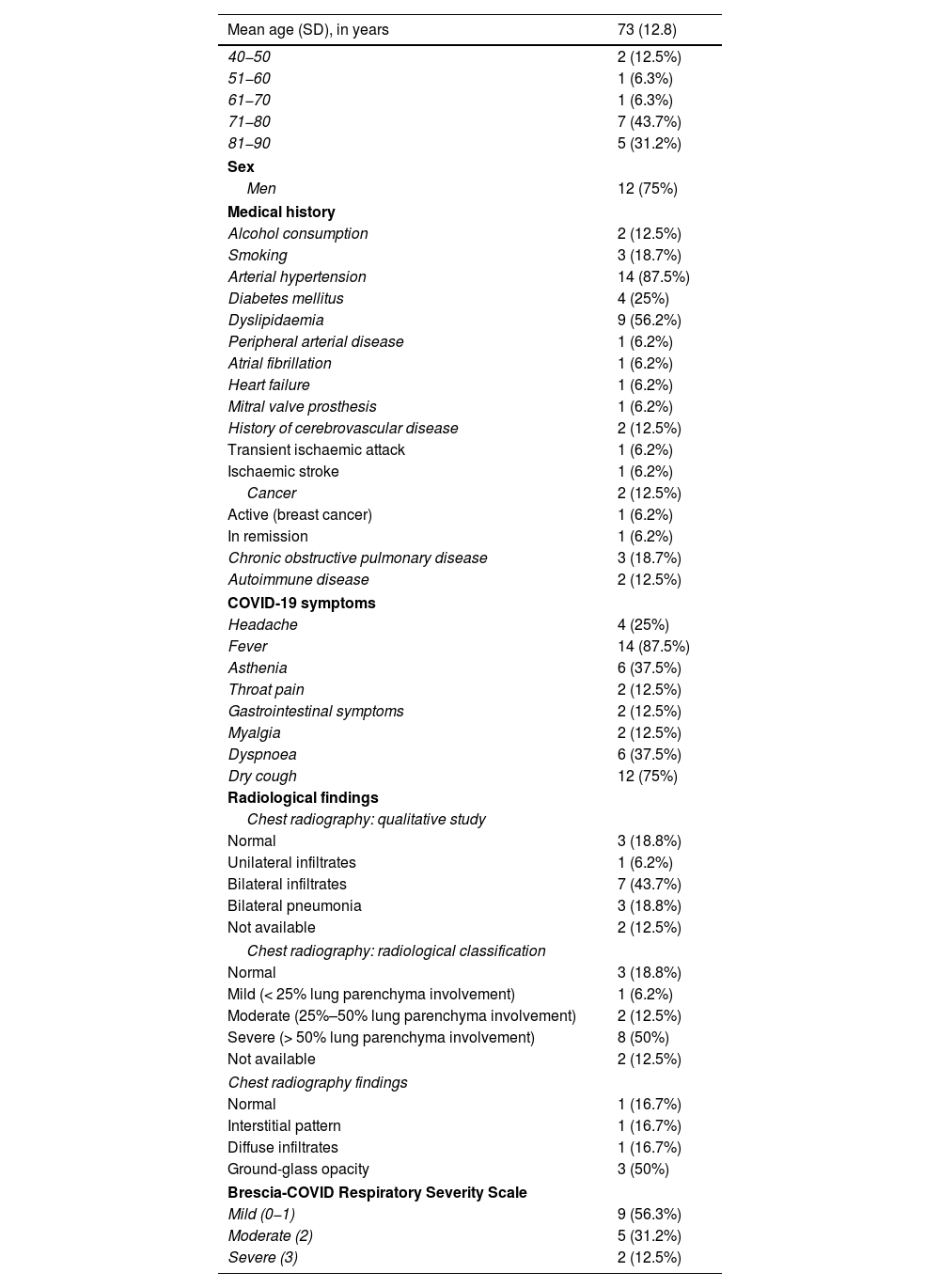

Tables 1–3 summarise the demographic, clinical, laboratory, hospital management, and functional prognostic characteristics of our sample.

Demographic, clinical, and radiological characteristics of our sample.

| Mean age (SD), in years | 73 (12.8) |

|---|---|

| 40−50 | 2 (12.5%) |

| 51−60 | 1 (6.3%) |

| 61−70 | 1 (6.3%) |

| 71−80 | 7 (43.7%) |

| 81−90 | 5 (31.2%) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 12 (75%) |

| Medical history | |

| Alcohol consumption | 2 (12.5%) |

| Smoking | 3 (18.7%) |

| Arterial hypertension | 14 (87.5%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (25%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 9 (56.2%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1 (6.2%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (6.2%) |

| Heart failure | 1 (6.2%) |

| Mitral valve prosthesis | 1 (6.2%) |

| History of cerebrovascular disease | 2 (12.5%) |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 1 (6.2%) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 1 (6.2%) |

| Cancer | 2 (12.5%) |

| Active (breast cancer) | 1 (6.2%) |

| In remission | 1 (6.2%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (18.7%) |

| Autoimmune disease | 2 (12.5%) |

| COVID-19 symptoms | |

| Headache | 4 (25%) |

| Fever | 14 (87.5%) |

| Asthenia | 6 (37.5%) |

| Throat pain | 2 (12.5%) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 2 (12.5%) |

| Myalgia | 2 (12.5%) |

| Dyspnoea | 6 (37.5%) |

| Dry cough | 12 (75%) |

| Radiological findings | |

| Chest radiography: qualitative study | |

| Normal | 3 (18.8%) |

| Unilateral infiltrates | 1 (6.2%) |

| Bilateral infiltrates | 7 (43.7%) |

| Bilateral pneumonia | 3 (18.8%) |

| Not available | 2 (12.5%) |

| Chest radiography: radiological classification | |

| Normal | 3 (18.8%) |

| Mild (< 25% lung parenchyma involvement) | 1 (6.2%) |

| Moderate (25%–50% lung parenchyma involvement) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Severe (> 50% lung parenchyma involvement) | 8 (50%) |

| Not available | 2 (12.5%) |

| Chest radiography findings | |

| Normal | 1 (16.7%) |

| Interstitial pattern | 1 (16.7%) |

| Diffuse infiltrates | 1 (16.7%) |

| Ground-glass opacity | 3 (50%) |

| Brescia-COVID Respiratory Severity Scale | |

| Mild (0−1) | 9 (56.3%) |

| Moderate (2) | 5 (31.2%) |

| Severe (3) | 2 (12.5%) |

CT: computed tomography; SD: standard deviation.

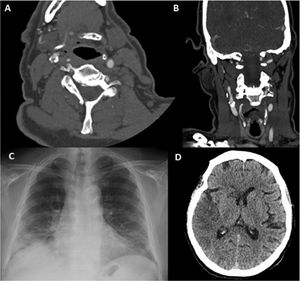

Laboratory findings in our sample.

| Test (reference range) | Mean (SD) | Abnormal results |

|---|---|---|

| Blood biochemistry | ||

| Sodium (135−145mmol/L) | 136.7 (3.8) | ↓ 6/16 (37.5%) |

| Potassium (3.5−145mmol/L) | 4.3 (0.5)b | ↑ 1/16 (6.2%) |

| ↓ 1/16 (6.2%) | ||

| Albumin (35−50g/La | 35 (6.75)b | ↓ 6/14 (42.9%) |

| Creatinine (53−106.1 μmol/L) | 70.25 (21.68)b | ↑ 2/16 (12.5%) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (7.5−17.9mmol/L) | 14.45 (7.13)b | ↑ 5/16 (31.2%) |

| AST (0.1−0.67 mkat/L) | 0.59 (0.45)b | ↑ 7/16 (43.8%) |

| ALT (0.1−0.67 mkat/L) | 0.33 (0.31)b | ↑ 4/16 (25%) |

| Bilirubin (5.1−18.8 μmol/L) | 12 (5.5)b | ↑ 2/16 (12.5%) |

| Glucose (3.3−5.5mmol/L) | 8.2 (2.5) | ↑ 14/16 (87.5%) |

| HbA1c (0.045−0.064a | 0.06 (0.0045)b | ↑ 2/7 (28.6%) |

| Total cholesterol (3.9−5.2mmol/La | 3.7 (1) | ↑ 1/12 (8.3%) |

| ↓ 7/12 (58.3%) | ||

| LDL (1.8−4.1mmol/La | 2.1 (0.8) | ↓ 3/12 (25%) |

| HDL (0.9−1.9mmol/La | 0.8 (0.4) | ↓ 9/12 (75%) |

| Triglycerides (0.34−2.26mmol/La | 1.7 (0.7) | ↑ 2/12 (16.7%) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (mkat/L) | 5 (2) | ↑ 9/16 (56.3%) |

| Creatine kinase (0.4−2.84 mkat/La | 1.7 (1) | ↑ 1/14 (7.1%) |

| ProBNP (10−125ng/La | 400 (1072)b | ↑ 9/10 (90%) |

| Troponin (0.0−0.06μg/L) | 0.02 (0.03)b | 0/16 (0%) |

| Complete blood count and NLR | ||

| Haemoglobin (120−170g/L) | 140.5 (24.75)† | ↓ 5/16 (31.2%) |

| Leukocyte count (4−11.5×109/L) | 9×109 (2×109) | ↑ 3/16 (18.7%) |

| Neutrophil count (1.5−7.5×109/L) | 6.8×109 (2.3×109) | ↑ 7/16 (43.8%) |

| Lymphocyte count (1.2−4.0×109/L) | 1.04±0.4 | ↓ 11/16 (68.8%) |

| NLR (< 3) | 6.8 (2.9) | ↑ 14/16 (87.5%) |

| Platelet count (150−400×109/L) | 291×109/L (139×109/L)b | ↑ 3/16 (18.7%) |

| Coagulation | ||

| INR (0.8−1.2) | 1.1 (0.1)b | ↑ 2/16 (12.5%) |

| Prothrombin time (11−15.3s) | 14.9 (2.2) | ↑ 6/16 (37.5%) |

| Thromboplastin time (29.2−39s) | 35.2 (8.8)b | ↑ 5/16 (31.2%) |

| Fibrinogen (4.4−13.2μmol/L) | 19.8 (4.98) | ↑ 15/16 (93.8%) |

| D-dimer (0.5−2.74nmol/L) | 16.4 (97)b | ↑ 14/16 (87.5%) |

| Acute-phase reactants | ||

| C-reactive protein (0.95−95.2nmol/L) | 1119.7 (942.7) | ↑ 13/16 (81.2%) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (0.0−13mm/ha | 67.7 (32.2) | ↑ 8/9 (88.9%) |

| Ferritin (67.4−674.1pmol/La | 1128.9 (807.9) | ↑ 8/14 (57.1%) |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate transaminase; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; INR: international normalised ratio; LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Characteristics of our patients with ischaemic stroke and COVID-19.

| Demographic characteristics | COVID-19–related variables | Laboratory findings | Neurological findings | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex/ethnicity | Personal history | Days from COVID-19 onset to stroke | Chest RX/CT | Severity (BCRSS) | COVID-19 treatment | LDH (mkat/L) | Lymphocyte count (× 109/L)/ NLR | CRP/ESR (nmol/L)/(mm/h) | D-dimer (nmol/L) | Fibrinogen (μmol/L) | Ferritin (pmol/L) | Baseline NIHSS score | Arterial territory | Aetiology: TOAST/ASCOD* | Complications | Reperfusion therapy | Hospitalisation (days) | Prognosis (mRS score) |

| 1 | 88 | W/white | AHT, hyperlipidaemia, breast cancer, CHF, mitral valve disease | 4 | Normal | 2 | HCL+L/R+IFN | 5 | 1.1/3.9 | 566.7/49 | 2.2 | 16 | 526 | 10 | Right MCA | Cardioembolism. A9S3C1O0D0 | No | No | 7 | Death (6) |

| 2 | 67 | M/white | AHT, hyperlipidaemia, AF, COPD | 12 | Bilateral pneumonia | 3 | HCL+L/R+IFN+CC | 3.7 | 1.6/3.5 | 1148.6/124 | 161 | 25.4 | 1489.8 | 21 | Left MCA. Tandem occlusion | Large-artery atherosclerosis. Endoluminal thrombus in carotid artery. | Cerebral oedema. ARDS | Intravenous fibrinolysis | 5 | Death (6) |

| A1S0C1O0D0 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 76 | M/white | AHT | 3 | Bilateral pneumonia | 3 | HCL+AZ+CC | 9.2 | 0.8/10.1 | 1217.2/NA | 23.2 | 19.7 | 1002.1 | 17 | Right MCA | Undetermined aetiology. A3S0C0O0D0 | Cerebral oedema. ARDS | Intravenous fibrinolysis+mechanical thrombectomy | 5 | Death (6) |

| 4 | 81 | M/white | AHT, DM, hyperlipidaemia, stroke, COPD | 13 | Bilateral pneumonia | 2 | HCL+IFN+CC | 4.6 | 0.9/10.5 | 2381/NA | 92.5 | 28.8 | NA | 23 | Left MCA | Undetermined aetiology. A9S3C0O3D9 | Cerebral oedema. ARDS | No | 2 | Death (6) |

| 5 | 77 | M/white | AHT, alcohol use, hyperlipidaemia, haematologic neoplasm | 13 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 2 | HCL+AZ | 5.7 | 0.7/9.1 | 1094.3/NA | 3701.7 | 17.8 | 2154.9 | 15 | Right MCA. Tandem occlusion | Large-artery atherosclerosis. A1S0C0O0D0 | No | Intravenous fibrinolysis | 16 | Moderate disability at discharge to rehabilitation centre (4) |

| 6 | 55 | W/white | Hyperlipidaemia, smoker, asthma | 16 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 2 | HCL+L/R | 4.1 | 1.1/9.5 | 1066.7/NA | 130.9 | 22.1 | NA | 20 | Right MCA. Tandem occlusion | Large-artery atherosclerosis. Endoluminal thrombus in carotid artery. A1S0C0O3D0 | Cerebral oedema | Intravenous fibrinolysis | 2 | Death (6) |

| 7 | 86 | M/white | AHT, smoker, alcohol use, COPD | 24 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 1 | HCL+AZ | 3.2 | 0.5/8.8 | 1171.5/81 | 14.2 | 18.7 | 132.6 | 18 | Right MCA | Undetermined aetiology. A9S3C0O3D9 | No | No | 3 | Death (6) |

| 8 | 74 | M/white | AHT, DM, hyperlipidaemia | 16 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 1 | HCL+AZ+L/R | 8.5 | 0.6/5.8 | 1455.3/NA | 9.3 | 22.3 | 1707.7 | 2 | Left ICA | Large-artery atherosclerosis. Endoluminal thrombus in carotid artery. A1S3C0O0D0 | No | No | 13 | Asymptomatic (0) |

| 9 | 89 | M/white | AHT | 1 | Unilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 0 | HCL+AZ | 3.3 | 1.8/2.5 | 82.9/48 | 3.8 | 13.9 | 305.6 | 3 | Right PCA | Undetermined aetiology. A3S3C0O0D0 | No | No | 4 | Mild disability (2) |

| 10 | 71 | M/white | – | 18 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 0 | HCL | 3.6 | 1.9/2.8 | 361.9/57 | 7.6 | 20.6 | 1101 | 1 | Right MCA | Large-artery atherosclerosis. Endoluminal thrombus in carotid artery. A1S0C0O0D0 | No | No | 4 | Asymptomatic (0) |

| 11 | 49 | W/Latino | AHT, lupus | 29 | Normal | 0 | – | 2.6 | 0.8/4.8 | 93.3/85 | 5.5 | 15.9 | 260.7 | 6 | Left anterior choroidal artery | Systemic lupus erythematosus. A3S0C0O1D0 | No | No | 30 | Mild disability (2) |

| 12 | 70 | M/white | AHT, hyperlipidaemia, smoker IPF under treatment with AZA | 10 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 1 | HCL+AZ | 6.4 | 0.9/6.8 | 981/NA | 21.4 | 22.6 | 2795.3 | 9 | Right MCA | Large-artery atherosclerosis. A1S0C3O3D0 | No | No | 12 | Moderate disability at discharge to rehabilitation centre (4) |

| 13 | 75 | M/white | AHT, DM, hyperlipidaemia, asthma | 18 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 2 | HCL+L/R+IFN+ tocilizumab+CC | 6 | 0.8/10.8 | 2381/80 | 3.8 | 26.8 | 548.3 | 1 | Left MCA | Large-artery atherosclerosis. Endoluminal thrombus in aortic arch. A1S0C0O0D0 | ARDS | No | 15 | Asymptomatic (0) |

| 14 | 79 | M/white | AHT, DM, hyperlipidaemia | 9 | Bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates | 1 | HCL+AZ+L/R+IFN | 6.9 | 0.5/9 | 3434.4/80 | 18.6 | 20.9 | 2485.2 | 9 | Right MCA | Large-artery atherosclerosis. A1S0C0O0D0 | ARDS | No | 3 | Death (6) |

| 15 | 49 | M/white | AHT, peripheral artery disease | 13 | Normal | 0 | – | 2 | 1.4/3.2 | 33.3/10 | 0.5 | 10.1 | 1119 | 1 | Left PCA | Large-artery atherosclerosis. A1S0C3O0D0 | Elevated levels of liver enzymes | No | 6 | Mild disability (1) |

| 16 | 85 | W/white | AHT, stroke | 15 | NA | 1 | HCL+AZ+CC | 5.3 | 1.4/7 | 445.7/NA | 8.2 | 14.7 | 435.9 | 2 | Left MCA | Undetermined aetiology. A3S3C0O0D0 | Pulmonary thromboembolism | No | 7 | Mild disability (1) |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AHT: arterial hypertension; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; AZ: azithromycin; AZA: azathioprine; CC: corticosteroids; CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; DM: diabetes mellitus; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HCL: hydroxychloroquine; ICA: internal carotid artery; IFN: interferon; IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; L/R: lopinavir/ritonavir; M: man; MCA: middle cerebral artery; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NA: not available; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PCA: posterior cerebral artery; RX/CT: radiography/computed tomography; W: woman. *ASCOD phenotyping: A: atherosclerosis; S: small-vessel disease; C: cardiac pathology; O: other causes.

Stroke aetiology was established according to the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification7 and the ASCOD criteria.8 Baseline functional status (before stroke) and disability at discharge were established with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS).9 The severity of COVID-19 was established with the Brescia-COVID Respiratory Severity Scale.10

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the patient data gathered (Tables 1–3); variables were expressed as different measures of central tendency and dispersion according to whether data were normally distributed. Some quantitative variables were treated as dichotomous, with results being classified as either normal or abnormal.

ResultsWe identified 22 patients with ischaemic stroke among 1594 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia; this represents a prevalence of ischaemic stroke of 1.38%. Six of these patients did not meet the inclusion criteria for our study. A total of 16 patients with acute focal cerebral ischaemia were included in our series (15 with ischaemic stroke and one with TIA).

Patients accessed the emergency department through different pathways. Four patients (25%) were transported directly by the Medical Emergency Service of the region of Madrid, 3 (18.7%) were transferred from other hospitals, 4 (25%) were in-hospital strokes (patients previously admitted to hospital due to COVID-19), and 5 (31.2%) arrived by their own means.

Mean time from onset of neurological symptoms to hospital admission was 326.5minutes (range, 192minutes to 72hours). Demographic, clinical, and radiological data are presented in Table 1 and laboratory data in Table 2.

Clinical data and outcomesMean (SD) time from COVID-19 symptom onset to stroke was 13 (7.5) days (range, 1–29). Ischaemic stroke most frequently occurred during the second week after onset of COVID-19 symptoms. The distribution was as follows: 18.7% of cases (n=3) during the first week, 43.8% (n=7) during the second week, 25% (n=4) during the third week, and 12.5% (n=2) during the fourth week. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at baseline (initial examination) was 9 (IQR: 16). Most patients scored 0-10 points (n=10; 62.5%), although a considerable percentage also scored 11–30 (4 patients [25%] scored 11–20 and 2 [12.5%] scored 21–30). Twelve patients (75%) presented large-vessel occlusion, which most frequently affected the middle cerebral artery (n=12; 80%).

Four patients (25%) were treated with revascularisation therapy: 3 received intravenous thrombolysis (18.8%) and the remaining patient was treated with intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy (6.3%).

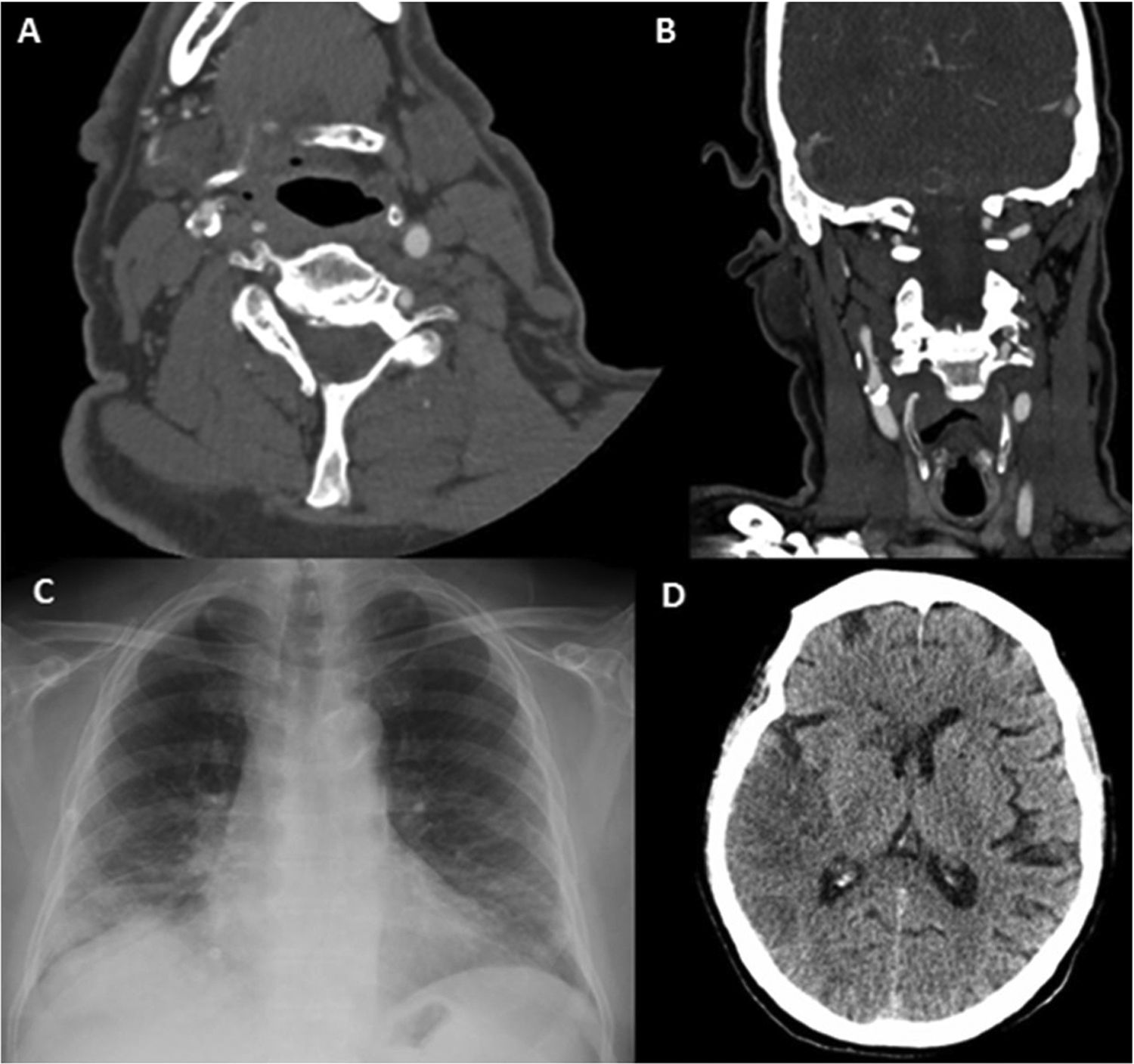

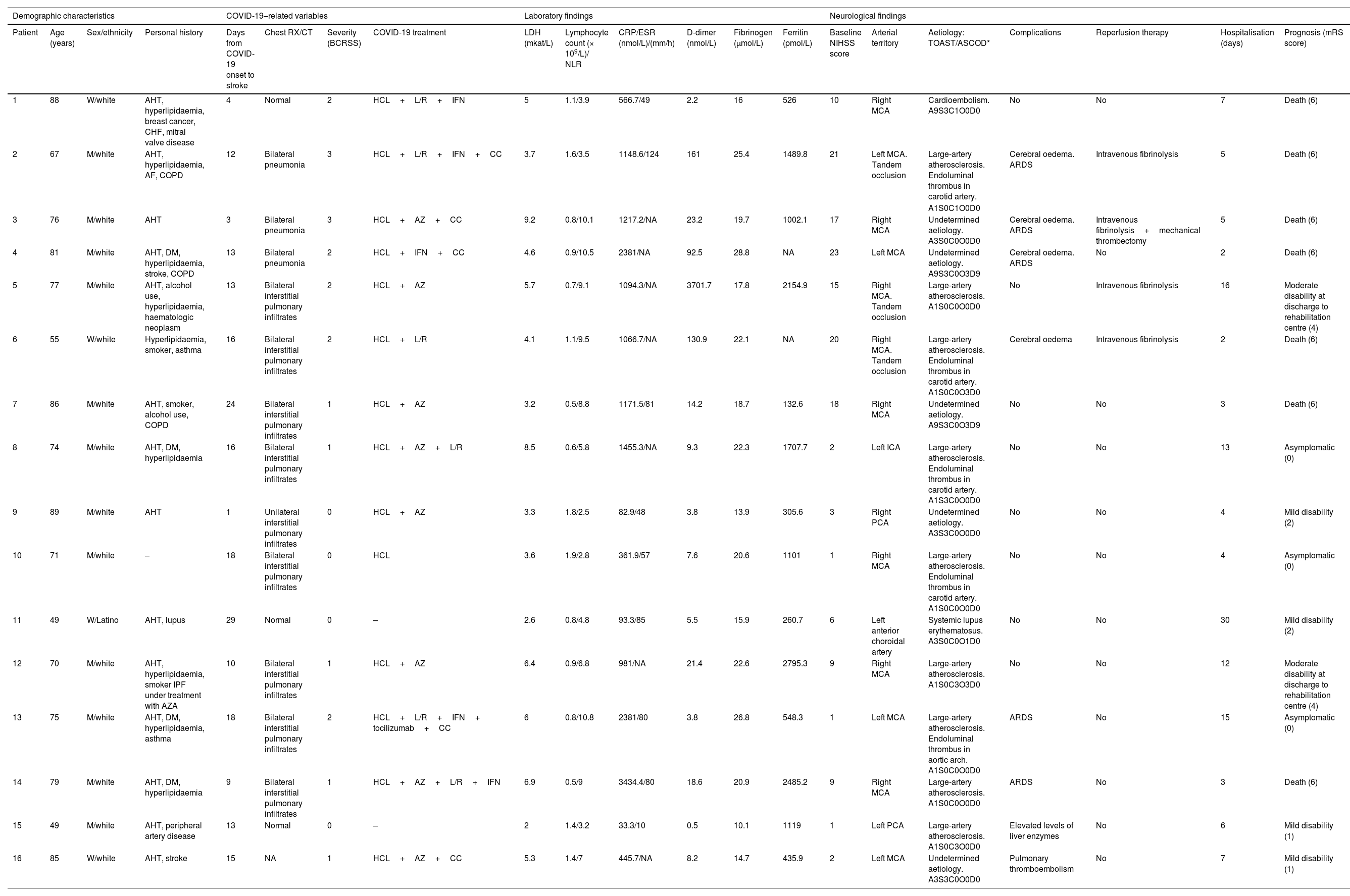

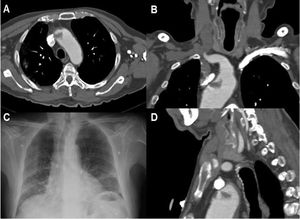

Regarding stroke aetiology, most cases were atherothrombotic (ASCOD phenotype A1; n=9, 56.3%). Of these, 5 patients (31.3%) presented endoluminal thrombi on atheromatous plaque (one in the aortic arch and the remaining 4 in the internal carotid artery). These endoluminal macrothrombi on atheromatous plaque correspond to subtypes A1.2 (ipsilateral atherosclerotic stenosis < 50% in an intra- or extracranial artery with an endoluminal thrombus supplying the ischaemic field) and A1.3 (mobile thrombus in the aortic arch). Three of these patients underwent CT angiography after a month of treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy and antithrombotic prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin; in these patients, the endoluminal thrombus resolved completely (Fig. 1).

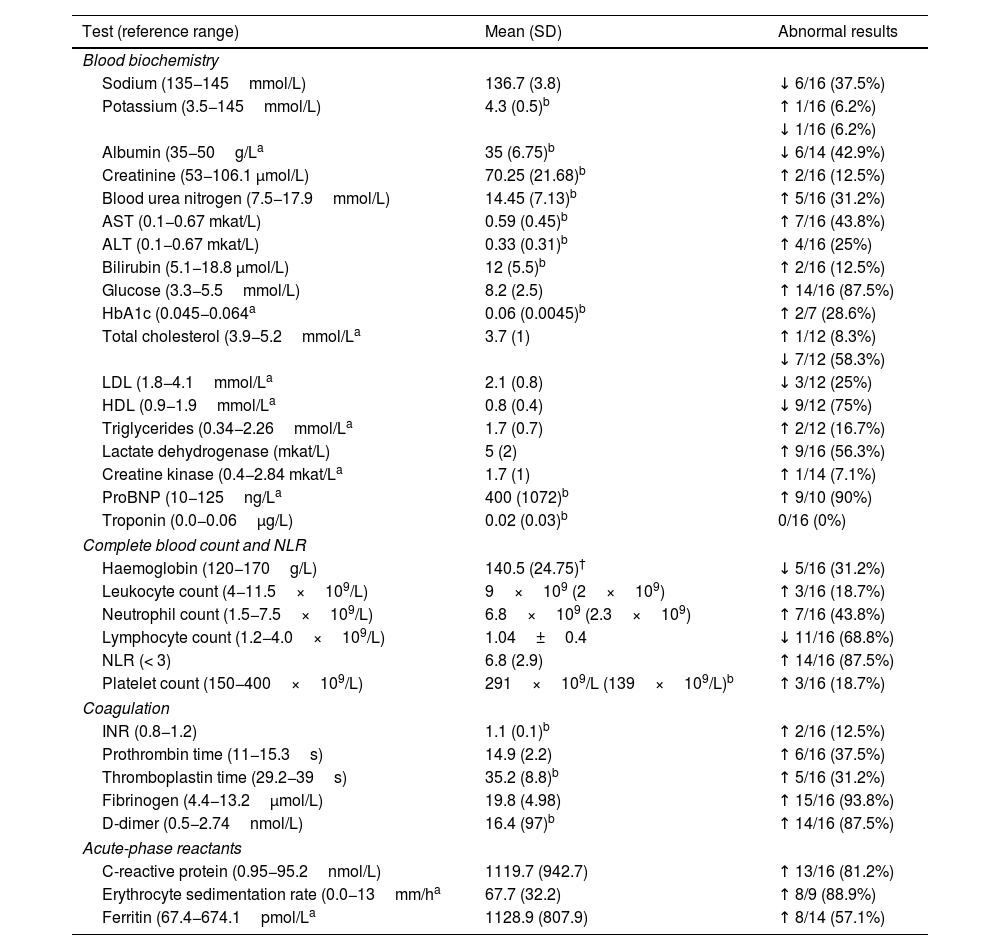

Patient 6. (A) Axial CT angiography image showing an endoluminal thrombus on atheromatous plaque in the right internal carotid artery. (B) Coronal CT angiography image showing an endoluminal thrombus on calcified atherosclerotic plaque. (C) Chest radiography showing bilateral diffuse pulmonary infiltrates due to COVID-19. (D) Non-contrast head CT scan revealing signs of infarction in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery.

Only one patient (6.3%) was diagnosed with possible cardioembolic stroke. However, we were unable to perform a vascular neuroimaging study with CT angiography in this patient as he died early due to poor baseline respiratory function. Therefore, we cannot rule out the copresence of 2 major causes of stroke. Another case was associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Stroke aetiology was undetermined in 5 cases, due to negative results in 3 (18.8%) and to an incomplete study in 2 (12.5%). No cases of stroke associated with small-vessel disease were found in our series.

The mean (SD) hospital stay in our sample was 8 (7) days. Outcomes were as follows: mRS 0–2 (asymptomatic or mild disability) in 7 patients (43.8%), mRS 3–5 (moderate-to-severe disability) in 2 (12.5%), and mRS 6 (death) in 7 (43.8%).

Regarding destination at discharge, 7 patients (43.8%) were discharged to their homes and 2 (12.5%) were discharged to rehabilitation centres.

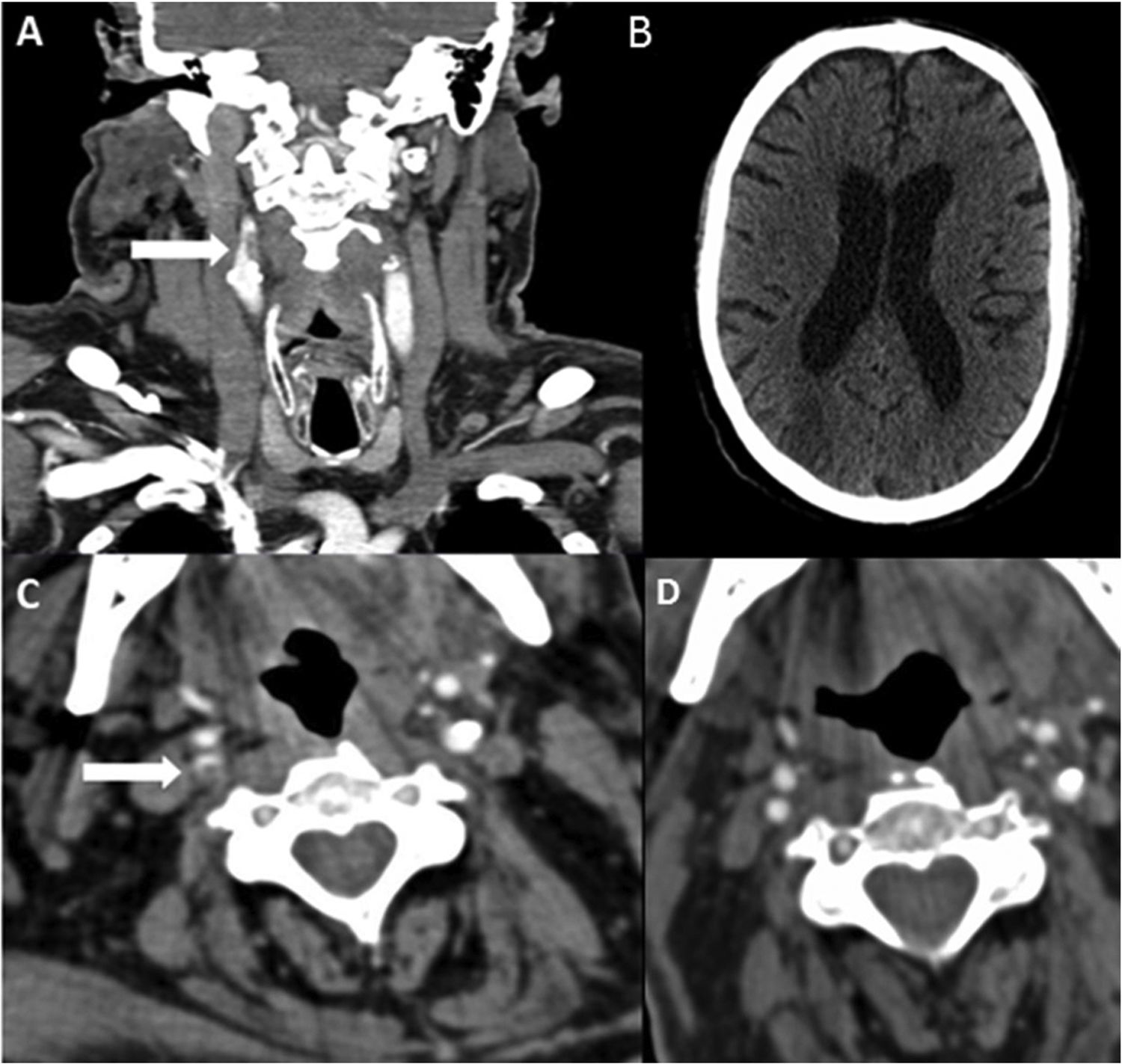

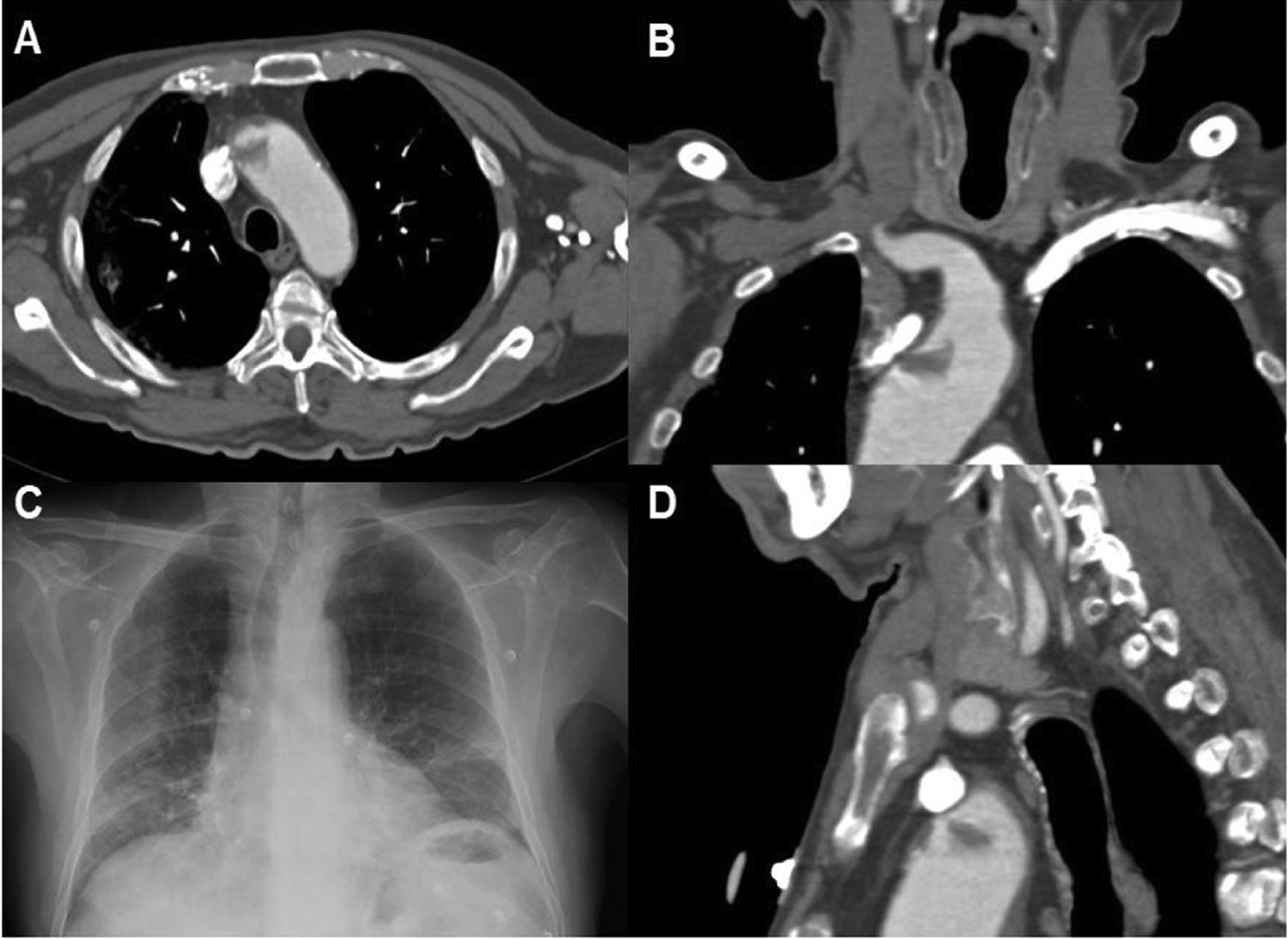

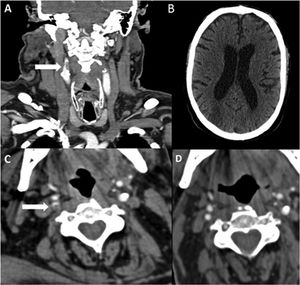

Table 3 presents the demographic, clinical, and laboratory data of our sample. Fig. 2 and 3 present images of the endoluminal thrombi identified in 2 patients in our series.

Patient 8. (A) Coronal CT angiography image revealing an endoluminal thrombus on atheromatous plaque (white arrow) in the right internal carotid artery. (B) Non-contrast head CT scan showing signs of infarction in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery. (C) Axial CT angiography image showing acute thrombosis in the right internal carotid artery (white arrow). (D) Follow-up study at 4 weeks: axial CT angiography image showing signs of resolution of the endoluminal thrombus, with atheromatous plaque causing 30% stenosis.

Patient 13. (A) Axial CT angiography image showing an endoluminal thrombus on atheromatous plaque in the ascending aortic arch. (B) Coronal CT angiography. (C) Chest radiography revealing bilateral diffuse infiltrates in the lower lobes, as well as laminar atelectasis. (D) Sagittal CT angiography image showing endoluminal thrombosis on atheromatous plaque in the aortic arch.

SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-strand RNA virus that enters human cells via the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2),11 which is widely expressed in alveolar cells, the vascular endothelium, and the central nervous system (glial cells and neurons).12 ACE2 plays a pivotal role in the renin-angiotensin system: its anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory properties counterbalance the vasoconstrictive effects of ACE1, angiotensin I, and angiotensin II, which have proinflammatory and procoagulant properties.13 SARS-CoV-2 decreases ACE2 levels, increasing the effects of ACE1 and angiotensin II; this predisposes to a cytokine storm and a hypercoagulable state that promotes thrombus formation.3

In fact, anatomical pathology studies have shown fibrinous thrombi in pulmonary arterioles and small arteries, as well as endothelial tumefaction and megakaryocytes in the pulmonary capillaries, all of which points to activation of the coagulation cascade.14

Since the beginning of the pandemic, several studies have described the neurological manifestations of COVID-19.1,2,15,16 A retrospective, observational study of a series of 214 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan (China) reported an incidence of neurological manifestations of 36.4%; cerebrovascular disease represented 2.8 % of all neurological manifestations, and was more frequent in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection than in mild cases (5.7% vs 0.8%).15

The frequency of ischaemic stroke in our series of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection is similar to that reported in a study analysing data from 3stroke centres in New York (0.9%),4 and lower than that reported in China (2.7%–2.8%).5,15

Studies including patients with stroke and SARS-CoV-2 infection reveal a high prevalence of vascular risk factors and history of cerebrovascular disease.2,4,5 History of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidaemia was also observed in our series (Table 1).

The most frequent symptom linked to the infection was fever, followed by muscle pain and dyspnoea. Chest radiography revealed severe infection in half of our patients (> 50% of lung parenchyma affected). Investigating the presence of these signs and symptoms in the context of the pandemic is essential. Chest radiography or CT studies may help to identify patients with stroke and COVID-19.

Regarding laboratory findings, some epidemiological studies have identified alterations in such inflammatory markers as leukocyte count, fibrinogen concentration, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration as independent risk factors for ischaemic stroke.17,18

Laboratory analyses revealed elevated CRP levels in most of our patients. CRP has thrombogenic properties as it induces the expression of monocyte tissue factor, a powerful activator of the extrinsic coagulation cascade that may act as a mediator of atherosclerosis-related thrombogenesis.19 CRP has been linked to the progression of carotid atherothrombosis, risk of a first ischaemic stroke,20 and the number of inflammatory cells on unstable atherosclerotic plaque.21

Fibrinogen and D-dimer concentrations have been found to be higher in patients with ischaemic stroke and COVID-19 than in patients with ischaemic stroke but no SARS-CoV-2 infection.4,5 All our patients presented fibrinogen concentrations > 88.4μmol/L (100mg/dL); this increase may be linked to thromboembolic events and may reflect a systemic prothrombotic state in SARS-CoV-2 infection, leading to poorer prognosis.22

Several articles have been published on the association between thrombogenesis and COVID-19.3,23 The cytokine storm leads to the activation of the coagulation cascade known as COVID-19–associated coagulopathy, characterised by increased levels of markers of hypercoagulability (D-dimer, fibrin, fibrinogen) and peripheral inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6), as well as mild thrombocytopenia.3

In our sample, a very high percentage of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (31%, n=5) presented atherothrombotic stroke with endoluminal thrombi on atheromatous plaque. This aetiological subtype of endoluminal thrombus is an infrequent cause of stroke, with a prevalence of 3.2% (that is, 10 times lower than in our sample).24 A prothrombotic state and severe inflammation secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection may promote the formation of an endoluminal macrothrombus on atheromatous plaque.25,26

Viral and bacterial infections have also been associated with increased risk of stroke. Risk increases after the infection (particularly in the first month) and decreases over time.27

These data are consistent with our results, according to which most patients presented stroke within 3 weeks of onset of COVID-19 symptoms. This period suggests an association with the systemic inflammatory response, rather than direct viral invasion.25

In patients presenting vascular risk factors, SARS-CoV-2 infection should be regarded as a trigger for stroke through an inflammatory procoagulant reaction. Some patients may present the conditions for rupture of atheromatous plaque and formation of an endoluminal macrothrombus.25,26

The high proportion of patients with stroke of undetermined aetiology may be related to the decreased access to complementary testing and poor short-term prognosis, which prevented us from completing a comprehensive study.

Another significant finding is the absence in our series of patients with stroke due to small-vessel disease; similar results were reported in the study by Yaghi et al.4 Future research should seek to confirm this finding.

Regarding prognosis, the mortality rate in our sample is lower than that reported in the study by Yaghi et al.4 (44% vs 63.6%), which may be related to the lower severity of respiratory involvement in our patients. Regardless, the mortality rate in our series is high when compared against that observed in patients with COVID-19 and not presenting stroke.28 Two mechanisms may explain the poorer prognosis of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and stroke: hypoxia-induced damage due to direct invasion of the blood-brain barrier, and immune-mediated brain damage.29 However, this poorer prognosis in hospitalised patients may be due to the fact that patients with minor symptoms did not travel to hospital due to the pandemic, or waited longer to visit hospital due to physical distancing or confinement measures.

The available evidence on medical treatment for stroke in the context of COVID-19 is insufficient. In our series, 3 of the 4 patients receiving reperfusion in the acute phase died. Regarding secondary prevention, 3 patients with endoluminal thrombi received dual antiplatelet therapy and prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin; a follow-up study performed one month later revealed disappearance of the thrombus in all 3. Studies currently underway will shed further light on the topic.

Stroke management in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is complicated by the reduced availability of emergency services, the need for physical distancing, isolation of infected individuals, and limited access to diagnostic tests. New strategies are needed to adapt stroke management for patients with COVID-19.30

Strengths and limitationsOur study included patients from a tertiary-level university hospital with a stroke unit that complies with recent recommendations on the management of patients with stroke and COVID-19.30

The hospital’s electronic medical records system enables access to patient clinical, laboratory, and radiological data. We included patients presenting stroke after diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, excluding patients who contracted the infection after stroke.

Our study is not without limitations. Firstly, as it included patients from a single centre, our findings cannot be extrapolated. Furthermore, diagnosis was inevitably affected by the context of the pandemic, which limited the availability of some diagnostic tests.

ConclusionsIn patients with COVID-19 and stroke, the most frequent aetiology is atherothrombotic (56%), with a high frequency of endoluminal thrombosis on atheromatous plaque (31%). Our data suggest that COVID-19–associated coagulopathy is a relevant aetiopathogenic mechanism for ischaemic stroke.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors wish to express their deepest gratitude to Dr Juan Antonio Zabala-Goiburú for his sage advice and unconditional support. They also thank Kathy Fitch for her editing services.