PRACTIC is an observational, epidemiological, multi-centre, prospective registry of patients admitted to the emergency room with acute stroke. We aim to study the impact of admission to a specialised neurology ward, either a Stroke Unit or by a Stroke Team, on several outcomes.

MethodsTen consecutive acute stroke patients admitted to the emergency room of 88 different hospitals of all levels of care in all regions of Spain were included. Only patients who gave informed consent were studied. Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project, TOAST subtypes and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) were determined. At six months, stroke or any other vascular recurrence was recorded.

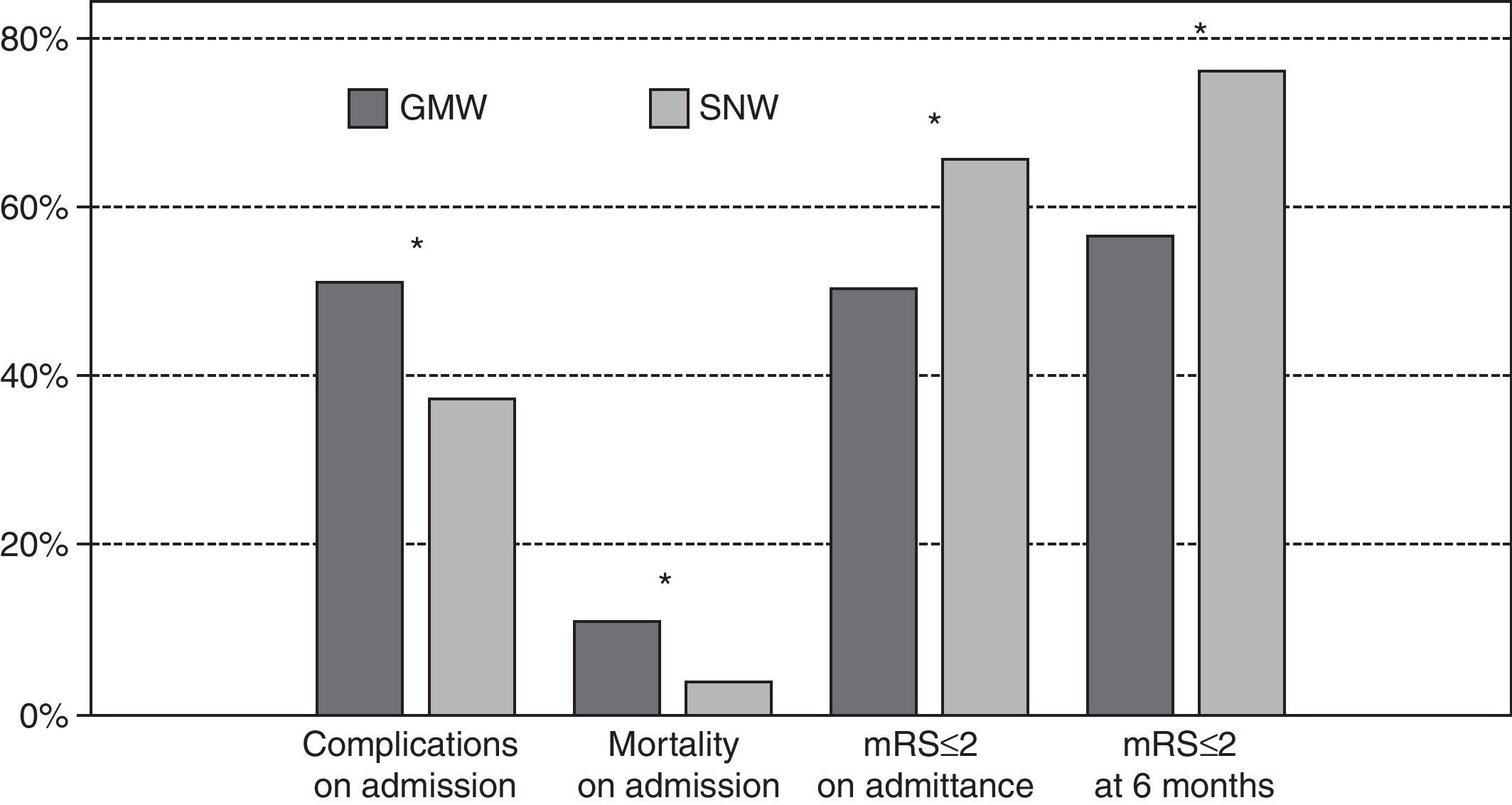

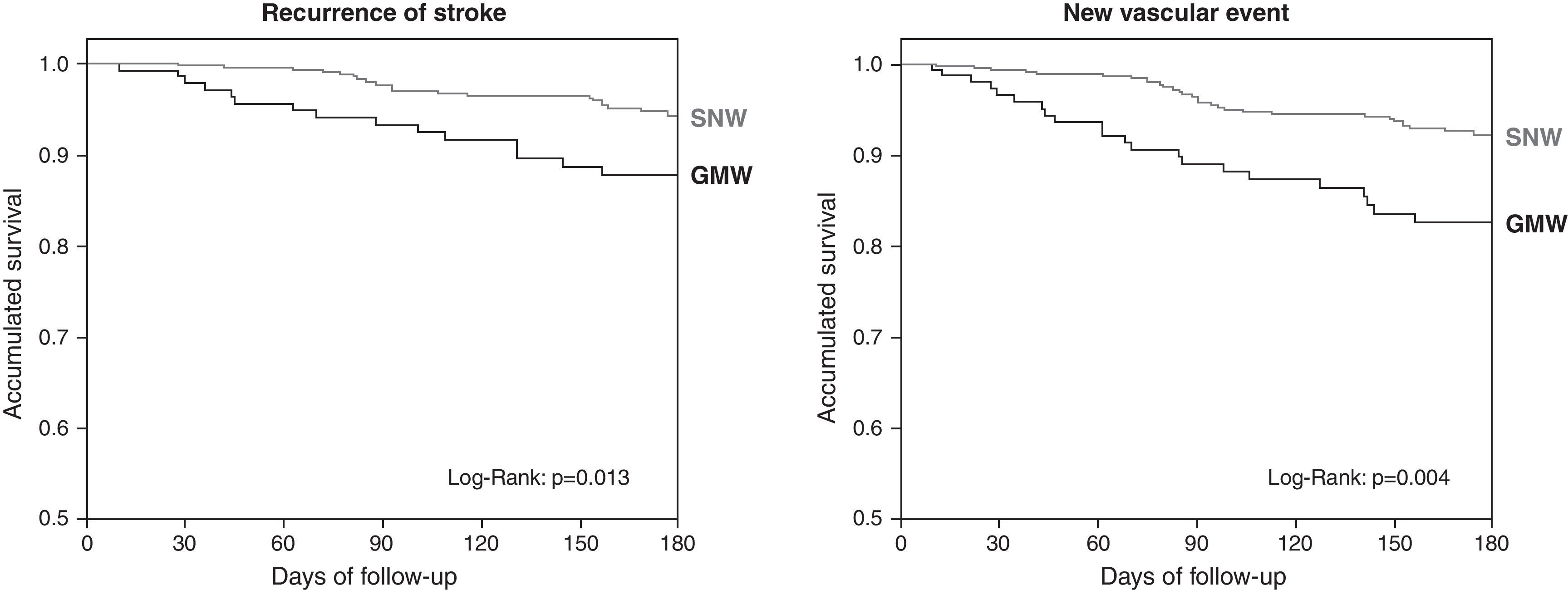

ResultsFrom a total of 864 patients, 729 (84.4%) were admitted; 555 (76.1%) in a specialised neurology ward (SNW) and 174 (23.9%) in a general medicine ward. Patients admitted in a SNW were younger and had higher rates of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH). Regarding outcomes, patients admitted to an SNW had lower rate of hospital complications (35.5 vs 50.6%; P<.001) higher rates of discharge mRS≤2 (65.4 vs 52.3%; P=.002) and lower mortality rates (2.9 vs 8.0%; P=.003). Adjusted logistic regression models showed that admission to a SNW reduces hospital complications (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.37–0.77; P=.001), hospital mortality (0.34, 0.15–0.77; P=.01) and a better prognosis at discharge, mRS≤2 (1.51, 1.00–2.29; P=.05). A better hospital outcome was observed for all ischemic stroke subtypes in an SNW, particularly for those with Partial Anterior Circulation Infarct. At six months, patients admitted to an SNW had higher percentages on the mRS≤2 (1.9, 1.08–3.27; P=.025), and lower rates of recurrent strokes (HR 0.49, 0.26–0.92; P=.025) or any vascular event (HR 0.50, 0.30–0.84; P=.009).

ConclusionsIn stroke patients, specialised neurological care, either in a Stroke Unit or by a Stroke Team, decreases mortality and hospital complications, thus lowering disability. A better outcome is sustained at 6 months when patients were admitted to an SNW. They have better functional status and lower rate of stroke or other vascular event recurrence. These data reinforce the need for specialised neurological hospital care for stroke patients.

PRACTIC es un registro observacional, epidemiológico, multicéntrico y prospectivo de pacientes atendidos en urgencias con ictus agudo. Nuestro objetivo es estudiar el impacto de una atención neurológica especializada, realizada por un equipo de ictus o en una Unidad de Ictus, en el pronóstico de estos pacientes.

MétodosSe incluyeron, de forma consecutiva, 10 pacientes con ictus agudo atendidos en urgencias de cada uno de los 88 hospitales de diferentes niveles asistenciales de todas las Comunidades Autónomas del Estado español. Se estudiaron solo aquellos pacientes de los cuales se obtenía un consentimiento informado. Se determinó la clasificación clínica del ictus por el Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project, la etiológica mediante criterios del TOAST y el pronóstico mediante la Escala de Rankin modificada (mRS). A los 6 meses se registraron la situación funcional y las recurrencias de ictus y de nuevos episodios vasculares producidos durante el seguimiento.

ResultadosDe un total de 864 pacientes, 729 (84,4%) fueron ingresados; 555 (76,1%) en una planta de Neurología (PN) y 174 (23,9%) en Medicina General (PMG). Los pacientes ingresados en una PN eran más jóvenes y presentaban mayor porcentaje de ictus isquémicos transitorios (AIT) y hemorragias intracerebrales (HIC). Respecto al pronóstico, los pacientes ingresados en una PN presentaron menos complicaciones intrahospitalarias (35,5% vs 50,6%; p<0,001), mayores porcentajes de mRS ≤ 2 al alta (65,4% vs 52,3%; p=0,002) y menos mortalidad (2,9 vs 8,0%; p=0,003). Tras realizar modelos de regresión logística ajustados se observó que el ingreso en una PN reduce las complicaciones (OR: 0,53; IC 95%: 0,37–0,77; p=0,001) y la mortalidad intrahospitalaria (0,34, 0,15–0,77; p=0,01), y aumenta el buen pronóstico por el mRS≤2 al alta (1,51, 1,00–2,29; p=0,05). El ingreso en una PN mostró una mejor evolución intrahospitalaria en todos los subtipos de ictus, especialmente aquellos con un ictus parcial en el territorio de la circulación anterior (PACI). A los 6 meses de seguimiento los pacientes que ingresaron en una PN presentaron mejor pronóstico (mRS≤2, OR: 1,9, 1,08–3,27; p=0,025) y menor riesgo de recurrencia de ictus (HR: 0,49, 0,26–0,92; p=0,025) y episodios vasculares (HR: 0,50, 0,30–0,84; p=0,009).

ConclusionesLa atención neurológica especializada, realizada por un equipo de ictus o en una Unidad de Ictus, de pacientes con ictus agudo, reduce la mortalidad y las complicaciones intrahospitalarias, e incrementa el porcentaje de personas que quedan sin discapacidad. Los pacientes ingresados en una PN también presentaron mejor pronóstico funcional a los 6 meses, con una menor recurrencia de ictus y de otros episodios vasculares durante el seguimiento. Estos datos refuerzan la necesidad de realizar una atención neurológica especializada a todos los pacientes con ictus durante su fase aguda.

Despite stroke being one of the greatest causes of death and the main cause for disability in western countries,1 care during hospital admission for acute stroke is not always carried out by a specialised neurologist. The introduction of fibrinolysis and other reperfusion therapies has revolutionised the handling of acute stokes, although it is important to stress that the benefits of these treatments depends on the doctor who administers them.2,3 Other general therapeutic measures such as admission to a specialised stroke unit4,5 or fast neurological care6 have also shown that they improve the outcome of these patients.

While the scientific community and the pharmaceutical industry are making great efforts in developing new treatments, it seems that the deployment of beneficial measures as simple as specialised neurological care are not evenly distributed among all the population. Geographic fairness for acute stroke care could be greatly beneficial in stroke outcome over the whole population.

The aim of the study was to assess the current state of hospital stroke care offered to the Spanish population, focusing basically on the availability of specialised neurological care in Spain and its possible short- and long-term benefits.

MethodsPRACTIC is an observational, epidemiological, multi-centre prospective registry in which each of the 88 different hospitals of all levels of care are represented throughout all the Autonomous Communities of the Spanish State. Ten consecutive acute stroke patients who attended the Emergency department of the hospital during the last 3 months of 2004 were included. Only patients or families who gave their informed consent were studied.

Information gathered for each patient included socio-demographic characteristics, comorbidities, neurological deficits, complications, diagnostic procedures, admittance procedures and treatment during hospital stay. Once the decision to be admitted was taken, the patient received treatment in either a conventional General Medicine ward (GMW) or in a specialised Neurology ward (SNW), according to availability at the hospital. We considered that the admission was to a SNW when the doctor in charge was a qualified neurologist and the care was carried out by a stroke team or in a stroke unit. All patients had a computerised tomography (CT) scan carried out. We included patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA), stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). The size, topography and severity of the stroke was assessed according to the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project Classification7,8 and the aetiological subtypes were established with the TOAST9 criteria. The scores for the modified Rankin scale (mRS>2)10 were used to assess functional disability at the time of discharge. The following types of complications registered during hospitalisation were collected: stroke progression and recurrence and infectious, thrombotic, metabolic or cardiac events. A follow-up at 6 months was also performed to assess the patient's functional situation and the presence or absence of stroke recurrence and/or new vascular events.

Statistical analysisData collection from the hospitals was standardised. Each hospital sent completed questionnaires to the coordinating centre, where all the information was checked for its credibility and proper completion, and an assessment on the quality of care for the stroke was also carried out.

The statistical analysis was performed using the statistics programme SPSS version 12.0 for Windows. The Pearson Chi squared test was used for the categorical variables and Fisher's exact test was used as needed. Student's t-test was used to compare the continuous variables, except in the modified Rankin scale on discharge, where the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used. Logistic regression models obtained through the step method were carried out to determine the factors that were independently associated to functional situation on discharge, complications during admission and mortality. Finally, the Cox regression analysis was used to identify possible independent predictors for stroke recurrence, new stroke episodes and mortality during the follow-up.

Tests carried out that gave a result of a significance level under 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsWe obtained informed consent from 864 patients out of 880, and these were included in the study. The average age was 70 years old and 520 patients (60%) were male. One hundred and sixty-four (19%) complied with TIA criteria and 61 (7.1%) were diagnosed with ICH.

The hospitals admitted 729 (84.4%) patients. From these, 555 (76.1%) were admitted to a SNW, 174 (23.9%) to a GMW and 23 (2.7%) to an intensive care unit. As to hospital level, 170 (19.7%) patients were admitted to level 1 hospitals, 287 (33.2%) to level 2 hospitals and 407 (47.1%) to level 3 hospitals. In the level 3 hospitals, there was much greater percentage of patients admitted to a SNW (89.4% vs 71.4% in a level 2 and 50.4% in level 1; P<0.001).

Only 77 (10.5%) patients were admitted to a stroke unit. This small group of patients was not comparable with the rest of the groups due to a greater ICH number (P=0.07). As a neurologist was in charge of these patients, and to avoid a possible bias in their inclusion, we decided to include them in the SNW.

Patients admitted to a GMW were older (71.6 vs 69.3; P=0.021) and there were no significant differences regarding gender and risk factors, except for alcoholism (29.9 GMW vs 17.7% SNW; P<0.001).

When we look at the treatment of patients admitted, intravenous thrombolysis was only administered in one SNW (2.3% vs 0%; P=0.046). A total of 18 patients received this treatment, which represented 2.8% of non-bleeding strokes and 5.3% of ischemic strokes, administered in a timeframe within the first 3h from the onset of the symptoms. On the other hand, prophylactic doses of anticoagulants were administered more frequently in a GMW (25.8% vs 47.7%; P<0.001). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups for the rest of the treatments. Patients admitted to a SNW had greater percentages of TIA (Table 1).

Characteristics according to admission ward.

| Medicine ward No.=174 (23.9%) | Specialised neurology ward No.=555 (76.1%) | P | |

| Age | 71.6 (10.6) | 69.3 (12.4) | 0.021 |

| Gender (male) | 61.3% | 59.5% | 0.671 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Smoking | 35.1% | 29.5% | 0.170 |

| Alcohol | 29.9% | 17.7% | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 41.4% | 33.9% | 0.071 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33.9% | 28.3% | 0.157 |

| Hypertension | 59.2% | 60.4% | 0.784 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 19.5% | 17.8% | 0.612 |

| Other cardioembolic pathologies | 9.2% | 4.9% | 0.108 |

| Previous stroke | 25.9% | 22.9% | 0.419 |

| Myocardial infarction | 9.2% | 7.6% | 0.489 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 6.3% | 4.0% | 0.192 |

| Previous mRS>2 | 10.9% | 7.2% | 0.117 |

| Clinical classification | |||

| TIA | 10.3% | 18.0% | 0.01 |

| TACI | 20.1% | 14.4% | 0.072 |

| PACI | 26.4% | 28.6% | 0.571 |

| LACI | 26.4% | 24.5% | 0.607 |

| POCI | 13.2% | 9.2% | 0.125 |

| ICH | 4.0% | 6.1% | 0.293 |

| Aetiology | |||

| Atherothrombotic | 34.9% | 36.7% | 0.838 |

| Cardioembolic | 23.5% | 22.1% | |

| Lacunar | 26.5% | 23.4% | |

| Undetermined | 13.9% | 15.9% | |

| Others | 1.2% | 1.9% | |

| Inpatient mortality | 8% | 2.9% | 0.003 |

| Inpatient complications | 50.6% | 35.5% | <0.001 |

| mRS on discharge | 2 (1–4) | 1 (1–3) | <0.001 |

| Destination on discharge | |||

| Home | 76.2% | 83.1% | 0.048 |

| Care home | 7.6% | 5.5% | |

| Rehabilitation centre | 7.0% | 7.5% | |

| Other hospital | 1.2% | 0.9% | |

| Death | 8.1% | 3.1% | |

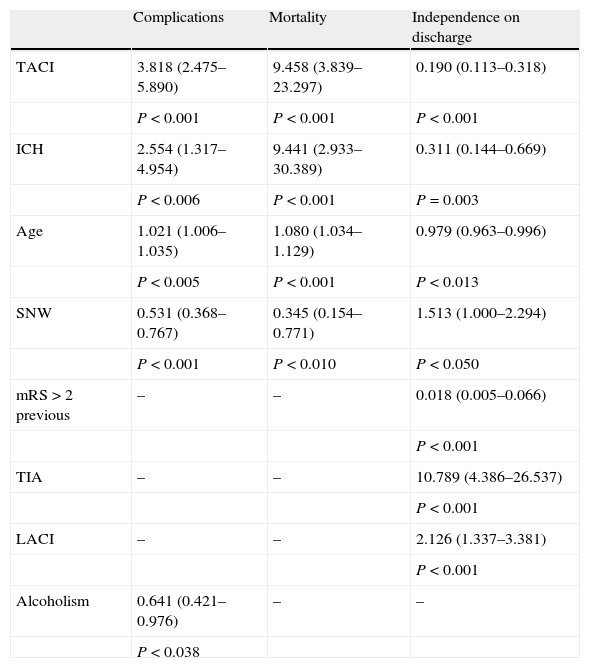

Patients admitted to a SNW have fewer inpatient complications (35.5% vs 50.6%; P<0.001), less disability on discharge (mRS≤2, 65.4% vs 52.3%; P=0.002) and lower mortality (2.9% vs 8.0%; P=0.003) (Fig. 1). With a logistic regression model adjusted by age and other risk factors, we obtained independent inpatient complication predictor factors: TACI (OR: 3.8; CI 95%: 2.5–5.9; P<0.001), admittance to a SNW (0.5, 0.4–0.8; P=0.001), ICH (2.6, 1.3–4.9; P=0.006), age (1.02, 1.01–1.04; P=0.005) and alcoholism (0.64, 0.42–0.97; P=0.038) (Table 2). The independent predictor factors of mRS≤2 on discharge were: TIA (10.8, 4.4–26.5; P<0.001), ICH (0.3, 0.1–0.7; P=0.003), admission to a SNW (1.5, 1.0–2.3; P=0.03), total anterior circulation infarct (TACI) (0.2, 0.1–0.3; P<0.001) and previous mRS>2 (0.02, 0.01–0.07; P<0.001) (Table 2). Better outcome when admitted to a SNW was observed with all the stroke subtypes, but especially in those that presented a partial anterior circulation infarct (PACI). Finally, admission to a SNW was also independently associated with a lesser mortality (OR: 0.345, 0.154–0.771; P=0.01) (Table 2).

Logistic regression analysis on prognosis on discharge.

| Complications | Mortality | Independence on discharge | |

| TACI | 3.818 (2.475–5.890) | 9.458 (3.839–23.297) | 0.190 (0.113–0.318) |

| P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | |

| ICH | 2.554 (1.317–4.954) | 9.441 (2.933–30.389) | 0.311 (0.144–0.669) |

| P<0.006 | P<0.001 | P=0.003 | |

| Age | 1.021 (1.006–1.035) | 1.080 (1.034–1.129) | 0.979 (0.963–0.996) |

| P<0.005 | P<0.001 | P<0.013 | |

| SNW | 0.531 (0.368–0.767) | 0.345 (0.154–0.771) | 1.513 (1.000–2.294) |

| P<0.001 | P<0.010 | P<0.050 | |

| mRS>2 previous | – | – | 0.018 (0.005–0.066) |

| P<0.001 | |||

| TIA | – | – | 10.789 (4.386–26.537) |

| P<0.001 | |||

| LACI | – | – | 2.126 (1.337–3.381) |

| P<0.001 | |||

| Alcoholism | 0.641 (0.421–0.976) | – | – |

| P<0.038 |

The functional outcome at 6 months was assessed in 548 patients, 75.2% of the patients admitted, with no differences among both groups (P=0.718). Three hundred and ninety-two (71.5%) patients were functionally independent. Table 3 shows all the variables associated with mRS≤2 at 6 months. After a logistic regression model adjusted for age, risk factors and stroke type, we observed again that admittance into a SNW independently predicted a good outcome (OR: 1.88; 1.08–3.27; P=0.025). During this period we observed 45 recurrences in 43 (5.9%) patients and 85 new vascular episodes in 64 (8.8%) patients. The variables associated to new vascular events are shown in Table 4. After a Cox regression model was undertaken, the associated independent variables for stroke recurrence were alcoholism (HR: 2.67, 1.45–4.92; P=0.002), initial TIA (HR: 2.09, 1.07–4.11; P=0.032) and admittance to a SNW (HR: 0.49; 0.26–0.92; P=0.025). Applying the same model, the associated independent variables for the appearance of new vascular events were alcoholism (HR: 1.93, 1.13–3.30; P=0.016), peripheral artery disease (HR: 3.29, 1.53–7.07; P=0.002) and admittance to a PANE (HR 0.50, 0.30–0.84; P=0.009). The survival curves carried out using the Kaplan–Meier method showed us the differences existing between the two groups at follow-up (Fig. 2).

Functional outcome at 6 months.

| Dependency or death (mRS>2) No.=156 (28.5%) | Independence (mRS≤2) No.=392 (71.5%) | P | Logistic regression odds ratio for mRS≤2 | |

| Age | 75.8 (10.5) | 68 (11.7) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.92–0.97); P<0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 58.3% | 61.0% | 0.569 | |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Smoking | 24.4% | 33.4% | 0.038 | |

| Alcohol | 16% | 22.2% | 0.106 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 37.2% | 34.7% | 0.583 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41.7% | 27.6% | 0.001 | 0.57 (0.34–0.96); P<0.034 |

| Hypertension | 68.6% | 56.4% | 0.008 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 32.1% | 12.2% | <0.001 | |

| Other cardioembolic pathologies | 4.5% | 2.3% | 0.171 | |

| Previous stroke | 34.6% | 19.6% | <0.001 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 16.7% | 10.7% | 0.056 | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 5.8% | 4.3% | 0.477 | |

| Previous mRS>2 | 74.4% | 98% | <0.001 | 20.6 (7.8–54.3); P<0.001 |

| Classification | ||||

| TIA | 5.8% | 20.2% | <0.001 | 2.76 (1.11–6.85); P<0.029 |

| TACI | 36.5% | 8.4% | <0.001 | 0.14 (0.07–0.26); P<0.001 |

| PACI | 27.6% | 29.8% | 0.596 | |

| LACI | 14.1% | 26% | 0.003 | |

| POCI | 7.1% | 12% | 0.090 | |

| ICH | 10.9% | 3.6% | 0.001 | 0.34 (0.13–0.93); P<0.035 |

| Aetiology | ||||

| Atherothrombotic | 41.0% | 36.6% | 0.001 | |

| Cardioembolic | 33.1% | 18.6% | ||

| Lacunar | 14.4% | 24.7% | ||

| Undetermined | 10.8% | 18.3% | ||

| Others | 0.7% | 1.9% | ||

| Neurology ward | 64.1% | 81.4% | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.08–3.27); P<0.025 |

Stroke recurrence and new vascular events.

| Stroke recurrence | P | New vascular event | P | |||

| No (No.=686) | Yes (No.=43) | No (No.=665) | Yes (No.=64) | |||

| Age | 69.8 (12.1) | 70.6 (10.7) | 0.672 | 69.8 (12.1) | 71.1 (10.6) | 0.384 |

| Gender (male) | 59.9% | 60.5% | 0.943 | 59.7% | 62.5% | 0.662 |

| Risk factors | ||||||

| Smoking | 30.2% | 41.9% | 0.108 | 29.8% | 42.2% | 0.040 |

| Alcohol | 19.2% | 41.9% | <0.001 | 19.2% | 34.4% | 0.004 |

| Dyslipidemia | 35.6% | 37.2% | 0.828 | 35.3% | 39.1% | 0.552 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28.9% | 41.9% | 0.070 | 28.9% | 37.5% | 0.149 |

| Hypertension | 60.3% | 55.8% | 0.556 | 60.5% | 56.3% | 0.512 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 18.1% | 20.9% | 0.638 | 18.0% | 20.3% | 0.654 |

| Other cardioembolic pathologies | 2.9% | 0% | 0.624 | 2.6% | 4.7% | 0.408 |

| Previous stroke | 22.9% | 34.9% | 0.072 | 22.6% | 34.4% | 0.033 |

| Myocardial infarction | 12.5% | 4.7% | 0.124 | 11.9% | 14.1% | 0.609 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 4.4% | 7% | 0.426 | 3.8% | 12.5% | 0.005 |

| Previous mRS>2 | 92% | 90.7% | 0.771 | 92% | 90.6% | 0.694 |

| Classification | ||||||

| TIA | 15.3% | 27.9% | 0.029 | 15.3% | 23.4% | 0.092 |

| TACI | 15.7% | 16.3% | 0.926 | 15.6% | 17.2% | 0.746 |

| PACI | 28% | 25.6% | 0.733 | 27.5% | 31.3% | 0.525 |

| LACI | 24.6% | 27.9% | 0.630 | 24.8% | 25% | 0.973 |

| POCI | 10.3% | 2.3% | 0.111 | 10.7% | 1.6% | 0.020 |

| ICH | 6% | 0% | 0.163 | 6% | 1.6% | 0.248 |

| Aetiology | ||||||

| Atherothrombotic | 36.2% | 37.2% | 0.882 | 35.3% | 46.0% | 0.385 |

| Cardioembolic | 22.5% | 20.9% | 22.8% | 19.0% | ||

| Lacunar | 24.2% | 23.3% | 24.7% | 19.0% | ||

| Undetermined | 15.2% | 18.6% | 15.4% | 15.9% | ||

| Others | 1.9% | 0% | 1.9% | 0% | ||

| Neurology ward | 77.0% | 62.8% | 0.034 | 77.3% | 64.1% | 0.018 |

The analysis register PRACTIC shows how nearly 24% of patients admitted to a hospital for acute stroke in Spain during 2004 did not receive specialised neurological care by a stroke team or a stroke unit, which is independently associated to a worse outcome on discharge. The patients admitted to a SNW also presented lower functional dependence, fewer stroke recurrences and fewer vascular events during the 6-month follow-up.

There is clear evidence that specialised neurological care2,6,11 or admittance to a stroke unit for patients with acute strokes is associated to significantly lower mortality rates, functional dependence and the need for institutionalisation.12,13 Despite knowing how beneficial stroke units are since 1980, their development and generalisation in modern countries is slow and incomplete. In Europe the percentage of patients admitted to a stroke unit varies from only 5% to 33%,14,15 despite the 1996 EUSI recommendations, which suggested that all patients with a stroke should have access to a stroke unit by the end of 2005.16 The PRACTIC study showed that, in Spain during 2004, only 10.5% of patients with a stroke were admitted to a stroke unit. As the development of multi-disciplinary stroke complexes represent greater economic efforts17 that are difficult to tackle, we wanted to investigate the impact on the short- and long-term outcomes of other measures such as admission to a ward run by a specialised neurology team. This measure could offer some benefits that are the same as those in stroke units, such as fast and precise stroke diagnosis,18,19 identification of patients at a high risk of worsening or the administration of new treatments.3 On the other hand, admittance to a SNW does not guarantee continuous patient monitoring.

As caring for disabled patients is expensive,20 even moderately effective stroke treatments can have a cost–effective relationship that is also high. Effective treatments applied to a greater number of patients with strokes will have a greater benefit on stroke morbidity. Although all patients are potential candidates for SNW admission, only a small minority will benefit from fibrinolytic treatment.21 The PRACTIC registry, which helped us gain a general view of stroke care in all communities in Spain, showed that, although there was a very high percentage of hospital admissions after care in the emergency departments (84%), nearly 24% of admissions were to a GMW. The impact of the presence of a specialised neurology team in the hospital was already observed during the first few hours; only centres having a SNW administered fibrinolytic treatment. However, the percentage of patients treated with t-PA in these centres was very low (2.8%) and we must intercede so that there is an increase in the administration of this treatment.22 Fibrinolysis in part explains the better outcome observed in these patients. However, after applying the logistic regression models adjusted by risk factors and use of fibrinolytic treatment, admittance to a SNW ward was still independently associated to low mortality, fewer inpatient complications and greater functional independence. We must stress that the best hospital outcome for patients admitted to a SNW was observed with all the stroke subtypes, but especially in those that presented a PACI. This is probably because patients at high risk of clinical worsening who are given a fast diagnosis and treatment benefit the most.

In short, a precise diagnosis and a better identification of the aetiology in a SNW could help improve strategies in secondary prevention, which lead to a lower recurrence rate for strokes and new vascular events. This is particularly relevant given that recurrent strokes are nearly twice as frequent as heart disease events in the first year from the onset of the stroke.23

The PRACTIC study was designed to present a view of current stroke care at hospital health levels in all Spanish geographical areas, despite the fact that the inclusion of the same number of patients per hospital could result in a bias towards the smaller hospitals.

The group of patients admitted to a SNW seems to be less serious (greater percentage of TIA and lesser age); however, these confusing variables were taken into account in the regression models. The initial seriousness of the stroke was determined by the OCSP classification, although there are obviously better scales to assess this variable. However, the nature of the study precluded its use, as the majority of doctors in a GMW are not trained or certified to use complex scales such as the NIHSS.

ConclusionsStroke patients who received specialised neurological care, carried out by a stroke team or a stroke unit, had lower mortality and inpatient complications, reducing the levels of disability. This improved outcome was maintained at 6 months, with a better functional state and a reduced recurrence rate or vascular events in patients admitted in a SNW ward. These data strengthen the need for specialised neurological care for stroke patients.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Alvarez-Sabín J, et al. Importancia de una atención neurológica especializada en el manejo intrahospitalario de pacientes con ictus. Neurología 2011;26:510–7.