Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a sensorimotor disorder characterised by an urge to move the legs, frequently associated with unpleasant sensations in the legs, and typically presenting in the evening or night and at rest.1 It often causes sleep alterations, and has a similar impact on quality of life to that associated with other chronic diseases.2 The pathophysiological mechanisms of RLS are poorly understood; however, response to dopaminergic agents and iron supplementation has given rise to a number of theories on its aetiopathogenesis.3 In addition to dopaminergic agonists and iron supplements, pharmacological treatment options also include α2δ ligands and some opioids.4 Non-pharmacological options include physical therapy; magnetic, electrical, or vibratory stimulation; and pneumatic compression devices.5 These may be used as complementary treatments when pharmacological treatment fails to achieve the desired response.

We describe the cases of 2 patients with RLS who presented partial response to pharmacological treatment. Patient 1: 70-year-old man with a 7-year history of RLS. In the previous year, he had been diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, generalised anxiety disorder, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, arterial hypertension, and obesity. During assessment at the sleep disorders clinic, chronic kidney disease was detected (glomerular filtration rate 30.77 mL/min), but no manifestations of neuropathy or anaemia were observed (Hb 14.7 g/dL), and ferritin levels were within the normal range (238 μg/mL). The patient was being treated with captopril, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and escitalopram. To treat RLS, he was receiving pramipexole 0.25 mg (administered at bedtime), but significant discomfort and sleep problems persisted. Patient 2: 55-year-old woman with 4-year history of RLS and history of osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia; the latter 2 conditions were diagnosed at the age of 52 years and were under treatment with duloxetine. Pramipexole dosed at 0.125 mg/night achieved little improvement, and was subsequently discontinued due to visual hallucinations. The patient also showed low ferritin levels (65 μg/mL). She was prescribed pregabalin 450 mg/day and ferrous fumarate 700 mg/day. Serum ferritin increased to 112 μg/mL, and the patient improved slightly, but the symptoms delaying sleep onset persisted. Both patients were indicated to use a compressive foot wrap (Restiffic®) as a complement to pharmacological treatment; they were instructed to use the device at night, when discomfort started. They were also instructed not to make any changes in the treatments they were taking for RLS or other comorbidities. We evaluated the symptoms of RLS at baseline and each week after treatment onset for 4 weeks, using the RLS rating scale (RLSRS) and patient-reported data.

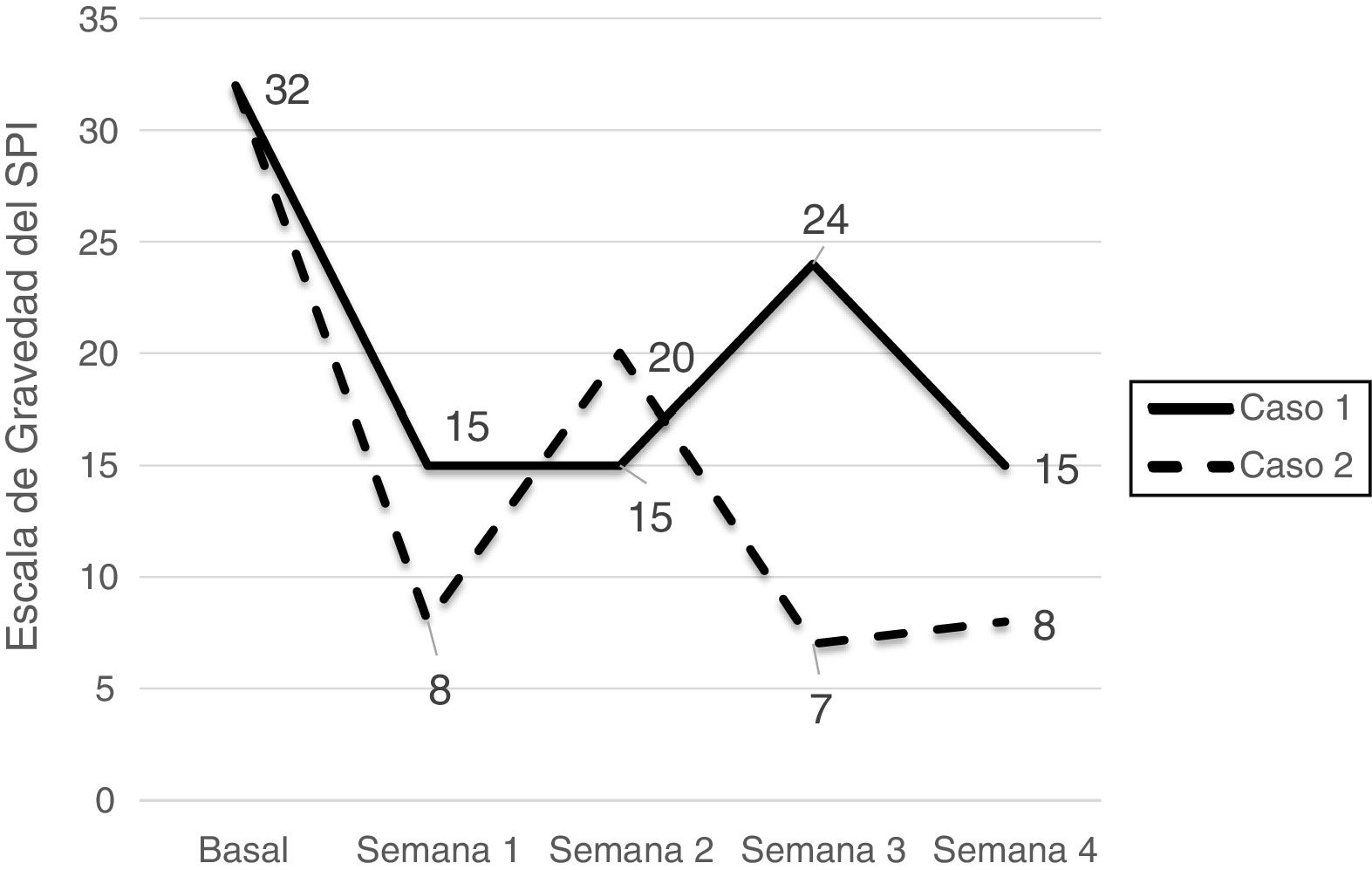

Symptom severity decreased remarkably in both patients, from very severe to moderate in the first patient (from 32 to 15 points) and from very severe to mild in the second (from 32 to 8 points). During follow-up, both patients reported not having used the device on some occasions, which led to symptom exacerbation (Fig. 1). They also reported transient irritation and oedema in the area covered by the foot wrap as the only adverse events.

Although several drugs are currently available for RLS, they may cause significant adverse effects (e.g., potentiation of the effects of dopaminergic agonists, especially levodopa) and may achieve poor or suboptimal results. Serum ferritin levels < 75 μg/mL may on occasion be associated with poorer treatment response; only one case has been reported of a patient with low serum ferritin in whom oral iron supplementation did not substantially modify response to RLS treatment. Non-pharmacological treatments are of particular interest in these cases, as in the patients described here, who had responded poorly to pharmacological treatment but achieved fast, substantial improvements with the foot compression device. Although the marked improvement in symptoms after the first week of use of the device may be due to a placebo effect, we observed a relatively steady decrease in symptoms over the following weeks. Furthermore, the improvement observed in our patients is similar to that described by Kuhn et al.,6 who reported a decrease of 15.5 points on the RLSRS after 5 to 8 weeks of treatment with the device.

In clinical practice, patients frequently resort to sensory stimulation of the legs, achieving varying degrees of relief. Massages and compression,7 pressure,6 and vibration devices have shown favourable results. The underlying mechanism of these improvements is unknown. It has been suggested that compression devices may improve local perfusion, reducing tissue hypoxia and ischaemia, particularly in peripheral nerves.7 Pressure and vibration devices, in turn, are thought to act as counterstimulants.6 The developers of the foot compression device speculate that sustained pressure on the abductor hallucis and flexor hallucis brevis muscles during the night induces relaxing motor cortex responses rather than muscle contraction. Despite a lack of evidence supporting this hypothesis, recent studies into the pathophysiology of RLS do suggest the presence of sensory and motor processing alterations in the spinal cord. It should be noted that application of tactile stimulation to the legs decreases leg discomfort in patients with RLS.8

Despite our encouraging results, there is a need for randomised, sham-controlled trials of the device to evaluate its efficacy and to determine its role as a complementary treatment in patients not responsive to pharmacological treatment or when the risks of a drug outweigh its benefits.

Please cite this article as: Osses-Rodríguez L, Urrea-Rodríguez A, Jiménez-Genchi A. Mejoría del síndrome de piernas inquietas con un dispositivo de presión plantar. Neurología. 2021;36:651–652.