Hypnic headache (HH), a primary headache first described by Raskin1 in 1988, is listed in group 4 of the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, beta version (ICHD-3 beta), which was published in 2013.2 HH usually begins after the age of 50 and presents as recurrent oppressive headache in most cases. This type of headache presents only during sleep, waking the patient (‘alarm clock’ headache) and lasting for up to 4 hours, without any characteristic associated symptoms. To diagnose HH, other possible causes of nocturnal headache must first be ruled out, with special attention to sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS), nocturnal hypertension, hypoglycaemia, and medication overuse. However, presence of SAHS does not rule out a diagnosis of HH.

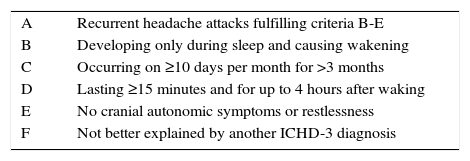

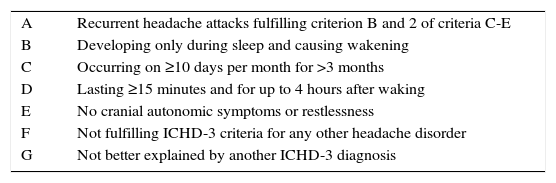

The ICHD-3 beta differentiates between hypnic headache (Table 1) and probable hypnic headache (Table 2).

ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria for hypnic headache.

| A | Recurrent headache attacks fulfilling criteria B-E |

| B | Developing only during sleep and causing wakening |

| C | Occurring on ≥10 days per month for >3 months |

| D | Lasting ≥15 minutes and for up to 4 hours after waking |

| E | No cranial autonomic symptoms or restlessness |

| F | Not better explained by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria for probable hypnic headache.

| A | Recurrent headache attacks fulfilling criterion B and 2 of criteria C-E |

| B | Developing only during sleep and causing wakening |

| C | Occurring on ≥10 days per month for >3 months |

| D | Lasting ≥15 minutes and for up to 4 hours after waking |

| E | No cranial autonomic symptoms or restlessness |

| F | Not fulfilling ICHD-3 criteria for any other headache disorder |

| G | Not better explained by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

We present the case of a 41-year-old woman with a history of essential hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, class II obesity, migraine without aura, and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome (OHS). She had been hospitalised due to a viral respiratory infection with influenza A; during her hospital stay she only required nasal cannula oxygen therapy in the first few days and experienced a mild headache that resolved as symptoms improved. In the month following discharge, our patient was referred to the headache unit due to episodes of headache appearing only at night (usually around 2.00-3.00 a.m.), with a frequency of 2-4 episodes. Headache was either hemicranial (affecting both sides) or holocranial, pulsating and stabbing, and of moderate intensity. Episodes lasted a mean of 15 minutes and made her get out of bed to engage in motor tasks until symptoms subsided completely. She displayed no other neurological signs or symptoms, whether general or local, except for occasional nausea.

Headache met the ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria for HH. A physical examination, analyses, and a neuroimaging study revealed no abnormalities, which ruled out symptomatic headache secondary to an intracranial structural process.

As HH was suspected, we started preventive treatment with lithium carbonate given that this is the most studied treatment for HH and our patient had no contraindications for this drug. Treatment achieved excellent response, with complete remission of the episodes. The treatment was discontinued once the patient had been asymptomatic for approximately 6 months, and headache episodes did not reappear.

Respiratory infection and essential hypertension (which exacerbates at night) may have played an important role in the pathogenesis of HH. However, other factors should also be considered, namely adequate management of hypertension during hospitalisation and the exceptional response to lithium carbonate before starting non-invasive mechanical ventilation, on the one hand, and the temporal connection between headache episodes and respiratory infection due to influenza A virus, on the other.

Although the literature describes a number of neurological complications associated with influenza A (H1N1) virus infection (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, myelitis, acute necrotising encephalitis, etc.3–6), these conditions occur during the acute phase of infection, which suggests a parainfectious immune-mediated aetiology.7,8 In theory, a direct association between influenza A virus infection and HH cannot be established since there is little understanding of the pathophysiology of either entity. However, given that other viruses have been suggested to be linked to other forms of primary headache,9–11 influenza A virus infection may be considered a potential trigger factor for HH in at-risk patients.

Although our patient was diagnosed with primary HH and received pharmacological treatment, we hypothesise that HH in this case may have been a subacute/chronic complication of influenza A virus infection. However, this hypothesis is not likely to be confirmed in the near future given the low frequency of influenza A virus infection (patients with HH rarely have a history of influenza according to the series described in the literature). In any case, HH should be considered within the spectrum of neurological alterations secondary to influenza A virus infection.

Please cite this article as: Pérez Hernández A, Gómez Ontañón E. ¿Virus de la gripe A como factor desencadenante de una cefalea hípnica? Neurología. 2017;32:67–68.

This study has not been presented at the SEN's Annual Meeting or at any other meetings or congresses, nor has it received funding from any public or private institutions.