Acute otitis media (AOM) is one of the most frequent reasons for visits to the paediatrician. While usually regarded as benign, AOM may also cause severe complications.

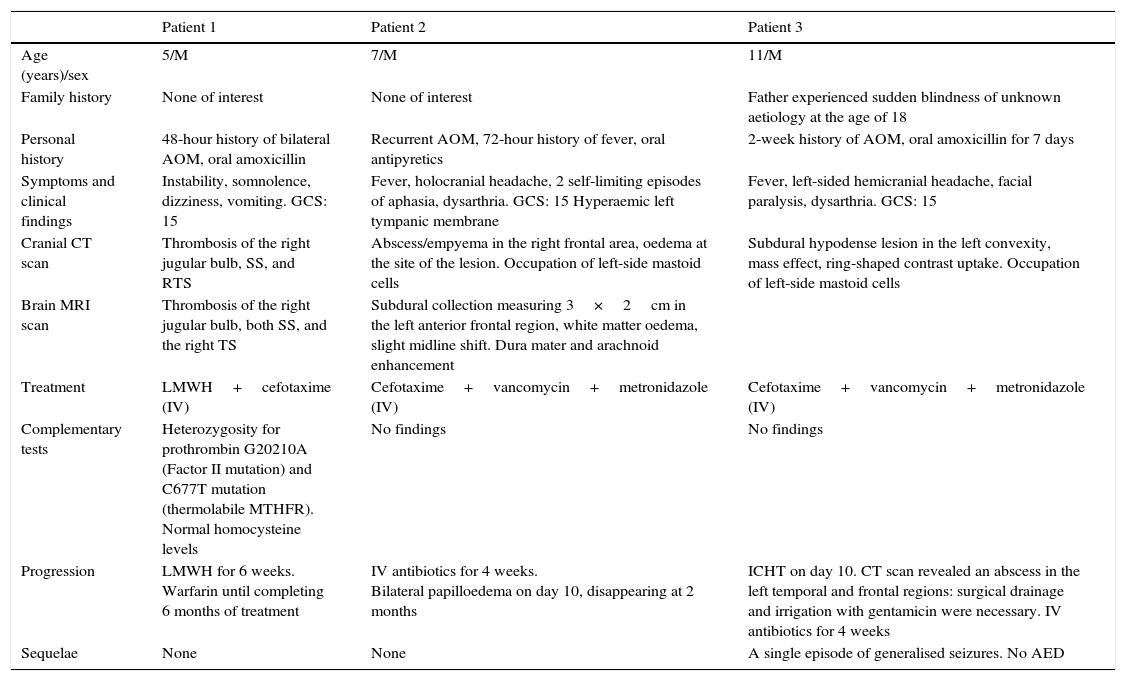

We present 3 clinical cases of AOM (Table 1) and provide a literature review of the intracranial complications (IC) of these infections.

Description of patients.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)/sex | 5/M | 7/M | 11/M |

| Family history | None of interest | None of interest | Father experienced sudden blindness of unknown aetiology at the age of 18 |

| Personal history | 48-hour history of bilateral AOM, oral amoxicillin | Recurrent AOM, 72-hour history of fever, oral antipyretics | 2-week history of AOM, oral amoxicillin for 7 days |

| Symptoms and clinical findings | Instability, somnolence, dizziness, vomiting. GCS: 15 | Fever, holocranial headache, 2 self-limiting episodes of aphasia, dysarthria. GCS: 15 Hyperaemic left tympanic membrane | Fever, left-sided hemicranial headache, facial paralysis, dysarthria. GCS: 15 |

| Cranial CT scan | Thrombosis of the right jugular bulb, SS, and RTS | Abscess/empyema in the right frontal area, oedema at the site of the lesion. Occupation of left-side mastoid cells | Subdural hypodense lesion in the left convexity, mass effect, ring-shaped contrast uptake. Occupation of left-side mastoid cells |

| Brain MRI scan | Thrombosis of the right jugular bulb, both SS, and the right TS | Subdural collection measuring 3×2cm in the left anterior frontal region, white matter oedema, slight midline shift. Dura mater and arachnoid enhancement | |

| Treatment | LMWH+cefotaxime (IV) | Cefotaxime+vancomycin+metronidazole (IV) | Cefotaxime+vancomycin+metronidazole (IV) |

| Complementary tests | Heterozygosity for prothrombin G20210A (Factor II mutation) and C677T mutation (thermolabile MTHFR). Normal homocysteine levels | No findings | No findings |

| Progression | LMWH for 6 weeks. Warfarin until completing 6 months of treatment | IV antibiotics for 4 weeks. Bilateral papilloedema on day 10, disappearing at 2 months | ICHT on day 10. CT scan revealed an abscess in the left temporal and frontal regions: surgical drainage and irrigation with gentamicin were necessary. IV antibiotics for 4 weeks |

| Sequelae | None | None | A single episode of generalised seizures. No AED |

AED, antiepileptic drugs; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; ICHT, intracranial hypertension; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; AOM, acute otitis media; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SS, sigmoid sinuses; CT, computed tomography; TS, transverse sinus.

ICs arise when inflammation extends to adjacent structures. The most frequent ICs are brain abscess, meningitis, venous sinus thrombosis (VST), and epidural and/or subdural abscess. The first 2 of these are typical in paediatric patients. Incidence of ICs, which decreased considerably with the advent of antibiotics, is estimated at 0.13% to 1.97%.1,2

In patient 1, the coagulation study revealed predisposition to thrombotic events. Prothrombin G20210A, or Factor II mutation, is associated with increased plasma prothrombin levels and activity, whereas the C677T mutation causes a thermolabile variant of MTHFR, leading to increased blood homocysteine levels which promote thrombosis and atherosclerosis.3

Patients 2 and 3 had mastoiditis. Dissemination of the infection via the emissary veins and direct erosion of the skull and the dura mater are thought to play a role in the development of brain abscess.4

The form of presentation differs depending on the type of IC. The main types of VST (lateral and/or transverse VST) are associated with intracranial hypertension,5,6 whereas seizures or paresis are more likely in patients with deep vein or cortical vein thrombosis.7 Patients with brain abscess most frequently present with non-specific symptoms: headache and fever occur in 50% to 80%, with lower percentages of vomiting and altered levels of consciousness.8 Antibiotics can mask initial signs and symptoms, which can hinder early diagnosis and treatment. In several published case series,9,10 numerous patients with ICs secondary to AOM had been treated with antibiotics; the highest percentage was 42.9% in the study by Migirov et al.9

No causal pathogen was isolated in any of the patients. According to the literature, mixed flora including Pseudomonas spp. and Proteus spp. are the most commonly reported in VST. The most frequent organisms in abscesses are Streptococcus (60%-70%), gram-negative anaerobes (20%-40%), and to a lesser extent, Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus aureus, and fungi.11

There is no consensus on the management of paediatric brain abscess; most of the available evidence is based on studies of adult populations. Conservative treatment is recommended when the patient is stable and the lesion is small, well-vascularised, and located in the cortical area, as in patient 2. This approach requires close follow-up with imaging studies.8,11

Recent review articles on VST treatment in children (grade IB) recommend starting treatment with sodium heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), followed by oral anticoagulants or LMWH for at least 3 months, even in the presence of local haemorrhage. Surgery is limited to patients who do not respond to conservative treatment.12,13

ICs usually have a favourable prognosis. Some 80% of patients with an abscess either recover completely or experience minor sequelae, frequently in the form of seizures, headache, and hemiparesis.14 In the case of VST, morbidity and mortality rates are correlated with baseline Glasgow Coma Scale scores. Indicators of a good prognosis are lack of damage to the parenchyma, older age, involvement of the lateral or sigmoid sinuses, and the possibility of receiving anticoagulants.15

ICs, although rare in paediatric patients, are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Performing an emergency CT scan is essential for diagnosis and early treatment since it can help prevent future complications and sequelae. This process should be managed by an interdisciplinary team including neuropaediatricians, otorhinolaryngologists, neurosurgeons, intensive care specialists, and microbiologists.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz del Olmo Izuzquiza I, de Arriba Muñoz A, Romero Gil R, López Pisón J. Otitis media aguda, ¿una enfermedad siempre banal? Complicaciones intracraneales: casos clínicos y revisión. Neurología. 2016;31:496–498.