Venlafaxine was the first serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) to be marketed in Spain, in 1995. This antidepressant is indicated for the treatment of major depressive episodes, generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia), as well as for preventing recurrence of major depressive episodes.1 Although the summary of product characteristics does not list neuropathic pain among the drug's indications, venlafaxine is considered a first-line treatment in the latest clinical management guidelines.2,3 After venlafaxine, other serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors were authorised in Spain, including duloxetine, indicated for the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in adults, and desvenlafaxine, with no indication for neuropathic pain.

The antidepressant effects of venlafaxine result from increased neurotransmitter activity in the central nervous system.4 Both venlafaxine and its active metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine are powerful serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and weak dopamine reuptake inhibitors. Neither drug has shown significant affinity for muscarinic, histamine, or α1 adrenergic receptors in vitro. Their action on these receptors is thought to be similar to the anticholinergic, sedative, and cardiovascular effects of other psychotropic drugs. Venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine do not inhibit monoamine oxidase activity.5

Our literature review aimed to provide updated information on the use of venlafaxine for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

DevelopmentWe searched the PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar databases in October 2017 using the following combinations of keywords: “venlafaxine and pain,” “venlafaxine and neuropathic pain,” “venlafaxine and neuropathy,” “SNRI and neuropathic pain,” “SNRI and neuropathy,” “serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and neuropathic pain,” and “serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and neuropathy.”

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients older than 18 years; neuropathic pain as the main indication for treatment with venlafaxine; venlafaxine in monotherapy; and studies and clinical trials (blinded and open-label randomised controlled trials and prospective, retrospective, and cross-sectional studies) published in English and reporting the effects of analgesic treatment with a scale and objectively analysing clinical response to venlafaxine. The exclusion criteria were as follows: review articles, case reports or case series, animal studies, studies published in any language other than English, studies using venlafaxine as a complementary treatment, and studies using venlafaxine for non-neuropathic pain or for conditions unrelated to pain.

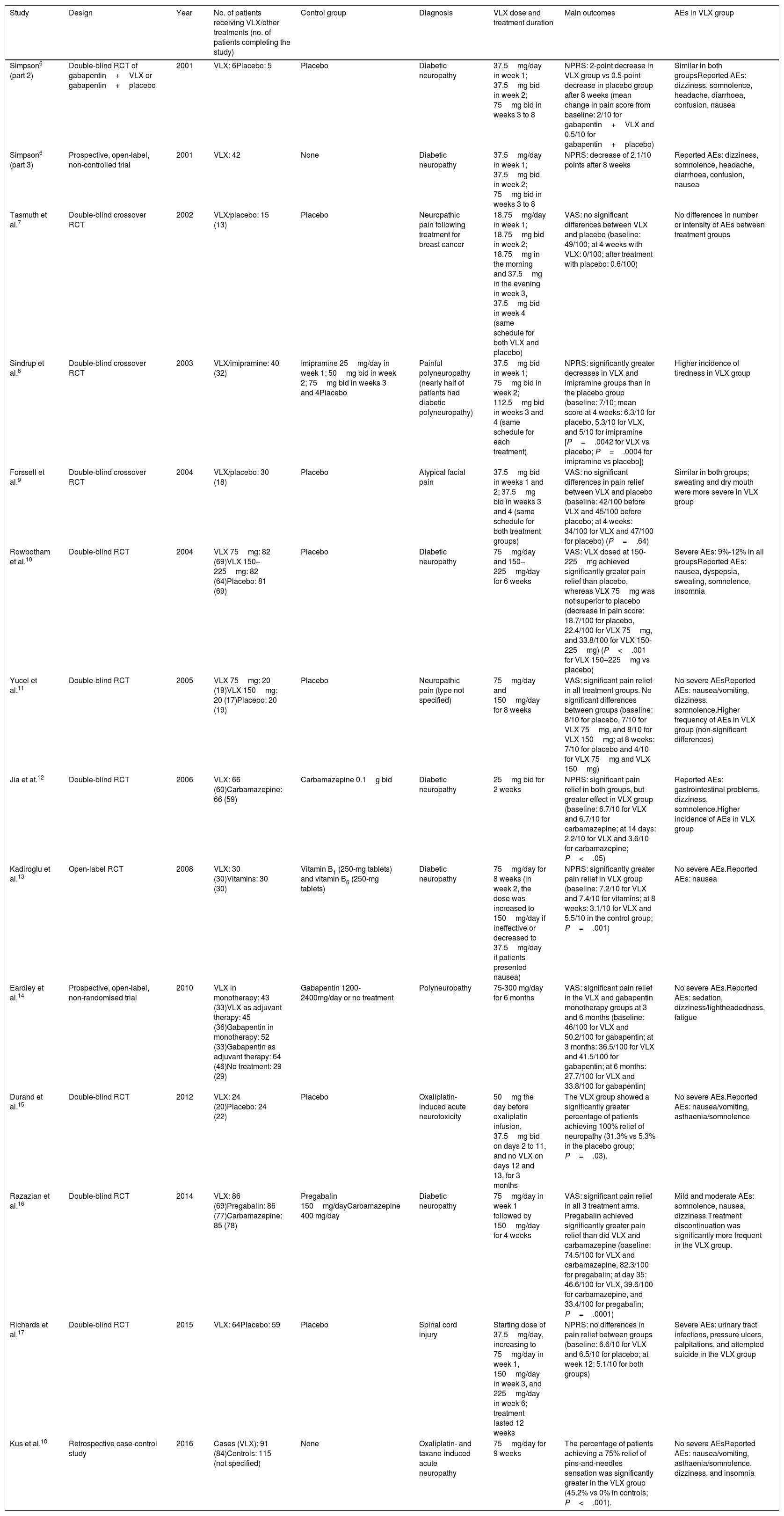

We finally included 13 studies6–18: 11 randomised clinical trials (RCT),6–13,15–17 a case-control study,18 and an open-label study.14Table 1 summarises the main results of the studies included.

Summary of the studies on venlafaxine for the treatment of neuropathic pain included in the review.

| Study | Design | Year | No. of patients receiving VLX/other treatments (no. of patients completing the study) | Control group | Diagnosis | VLX dose and treatment duration | Main outcomes | AEs in VLX group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson6 (part 2) | Double-blind RCT of gabapentin+VLX or gabapentin+placebo | 2001 | VLX: 6Placebo: 5 | Placebo | Diabetic neuropathy | 37.5mg/day in week 1; 37.5mg bid in week 2; 75mg bid in weeks 3 to 8 | NPRS: 2-point decrease in VLX group vs 0.5-point decrease in placebo group after 8 weeks (mean change in pain score from baseline: 2/10 for gabapentin+VLX and 0.5/10 for gabapentin+placebo) | Similar in both groupsReported AEs: dizziness, somnolence, headache, diarrhoea, confusion, nausea |

| Simpson6 (part 3) | Prospective, open-label, non-controlled trial | 2001 | VLX: 42 | None | Diabetic neuropathy | 37.5mg/day in week 1; 37.5mg bid in week 2; 75mg bid in weeks 3 to 8 | NPRS: decrease of 2.1/10 points after 8 weeks | Reported AEs: dizziness, somnolence, headache, diarrhoea, confusion, nausea |

| Tasmuth et al.7 | Double-blind crossover RCT | 2002 | VLX/placebo: 15 (13) | Placebo | Neuropathic pain following treatment for breast cancer | 18.75mg/day in week 1; 18.75mg bid in week 2; 18.75mg in the morning and 37.5mg in the evening in week 3, 37.5mg bid in week 4 (same schedule for both VLX and placebo) | VAS: no significant differences between VLX and placebo (baseline: 49/100; at 4 weeks with VLX: 0/100; after treatment with placebo: 0.6/100) | No differences in number or intensity of AEs between treatment groups |

| Sindrup et al.8 | Double-blind crossover RCT | 2003 | VLX/imipramine: 40 (32) | Imipramine 25mg/day in week 1; 50mg bid in week 2; 75mg bid in weeks 3 and 4Placebo | Painful polyneuropathy (nearly half of patients had diabetic polyneuropathy) | 37.5mg bid in week 1; 75mg bid in week 2; 112.5mg bid in weeks 3 and 4 (same schedule for each treatment) | NPRS: significantly greater decreases in VLX and imipramine groups than in the placebo group (baseline: 7/10; mean score at 4 weeks: 6.3/10 for placebo, 5.3/10 for VLX, and 5/10 for imipramine [P=.0042 for VLX vs placebo; P=.0004 for imipramine vs placebo]) | Higher incidence of tiredness in VLX group |

| Forssell et al.9 | Double-blind crossover RCT | 2004 | VLX/placebo: 30 (18) | Placebo | Atypical facial pain | 37.5mg bid in weeks 1 and 2; 37.5mg bid in weeks 3 and 4 (same schedule for both treatment groups) | VAS: no significant differences in pain relief between VLX and placebo (baseline: 42/100 before VLX and 45/100 before placebo; at 4 weeks: 34/100 for VLX and 47/100 for placebo) (P=.64) | Similar in both groups; sweating and dry mouth were more severe in VLX group |

| Rowbotham et al.10 | Double-blind RCT | 2004 | VLX 75mg: 82 (69)VLX 150–225mg: 82 (64)Placebo: 81 (69) | Placebo | Diabetic neuropathy | 75mg/day and 150–225mg/day for 6 weeks | VAS: VLX dosed at 150-225mg achieved significantly greater pain relief than placebo, whereas VLX 75mg was not superior to placebo (decrease in pain score: 18.7/100 for placebo, 22.4/100 for VLX 75mg, and 33.8/100 for VLX 150-225mg) (P<.001 for VLX 150–225mg vs placebo) | Severe AEs: 9%-12% in all groupsReported AEs: nausea, dyspepsia, sweating, somnolence, insomnia |

| Yucel et al.11 | Double-blind RCT | 2005 | VLX 75mg: 20 (19)VLX 150mg: 20 (17)Placebo: 20 (19) | Placebo | Neuropathic pain (type not specified) | 75mg/day and 150mg/day for 8 weeks | VAS: significant pain relief in all treatment groups. No significant differences between groups (baseline: 8/10 for placebo, 7/10 for VLX 75mg, and 8/10 for VLX 150mg; at 8 weeks: 7/10 for placebo and 4/10 for VLX 75mg and VLX 150mg) | No severe AEsReported AEs: nausea/vomiting, dizziness, somnolence.Higher frequency of AEs in VLX group (non-significant differences) |

| Jia et at.12 | Double-blind RCT | 2006 | VLX: 66 (60)Carbamazepine: 66 (59) | Carbamazepine 0.1g bid | Diabetic neuropathy | 25mg bid for 2 weeks | NPRS: significant pain relief in both groups, but greater effect in VLX group (baseline: 6.7/10 for VLX and 6.7/10 for carbamazepine; at 14 days: 2.2/10 for VLX and 3.6/10 for carbamazepine; P<.05) | Reported AEs: gastrointestinal problems, dizziness, somnolence.Higher incidence of AEs in VLX group |

| Kadiroglu et al.13 | Open-label RCT | 2008 | VLX: 30 (30)Vitamins: 30 (30) | Vitamin B1 (250-mg tablets) and vitamin B6 (250-mg tablets) | Diabetic neuropathy | 75mg/day for 8 weeks (in week 2, the dose was increased to 150mg/day if ineffective or decreased to 37.5mg/day if patients presented nausea) | NPRS: significantly greater pain relief in VLX group (baseline: 7.2/10 for VLX and 7.4/10 for vitamins; at 8 weeks: 3.1/10 for VLX and 5.5/10 in the control group; P=.001) | No severe AEs.Reported AEs: nausea |

| Eardley et al.14 | Prospective, open-label, non-randomised trial | 2010 | VLX in monotherapy: 43 (33)VLX as adjuvant therapy: 45 (36)Gabapentin in monotherapy: 52 (33)Gabapentin as adjuvant therapy: 64 (46)No treatment: 29 (29) | Gabapentin 1200-2400mg/day or no treatment | Polyneuropathy | 75-300 mg/day for 6 months | VAS: significant pain relief in the VLX and gabapentin monotherapy groups at 3 and 6 months (baseline: 46/100 for VLX and 50.2/100 for gabapentin; at 3 months: 36.5/100 for VLX and 41.5/100 for gabapentin; at 6 months: 27.7/100 for VLX and 33.8/100 for gabapentin) | No severe AEs.Reported AEs: sedation, dizziness/lightheadedness, fatigue |

| Durand et al.15 | Double-blind RCT | 2012 | VLX: 24 (20)Placebo: 24 (22) | Placebo | Oxaliplatin-induced acute neurotoxicity | 50mg the day before oxaliplatin infusion, 37.5mg bid on days 2 to 11, and no VLX on days 12 and 13, for 3 months | The VLX group showed a significantly greater percentage of patients achieving 100% relief of neuropathy (31.3% vs 5.3% in the placebo group; P=.03). | No severe AEs.Reported AEs: nausea/vomiting, asthaenia/somnolence |

| Razazian et al.16 | Double-blind RCT | 2014 | VLX: 86 (69)Pregabalin: 86 (77)Carbamazepine: 85 (78) | Pregabalin 150mg/dayCarbamazepine 400 mg/day | Diabetic neuropathy | 75mg/day in week 1 followed by 150mg/day for 4 weeks | VAS: significant pain relief in all 3 treatment arms. Pregabalin achieved significantly greater pain relief than did VLX and carbamazepine (baseline: 74.5/100 for VLX and carbamazepine, 82.3/100 for pregabalin; at day 35: 46.6/100 for VLX, 39.6/100 for carbamazepine, and 33.4/100 for pregabalin; P=.0001) | Mild and moderate AEs: somnolence, nausea, dizziness.Treatment discontinuation was significantly more frequent in the VLX group. |

| Richards et al.17 | Double-blind RCT | 2015 | VLX: 64Placebo: 59 | Placebo | Spinal cord injury | Starting dose of 37.5mg/day, increasing to 75mg/day in week 1, 150mg/day in week 3, and 225mg/day in week 6; treatment lasted 12 weeks | NPRS: no differences in pain relief between groups (baseline: 6.6/10 for VLX and 6.5/10 for placebo; at week 12: 5.1/10 for both groups) | Severe AEs: urinary tract infections, pressure ulcers, palpitations, and attempted suicide in the VLX group |

| Kus et al.18 | Retrospective case-control study | 2016 | Cases (VLX): 91 (84)Controls: 115 (not specified) | None | Oxaliplatin- and taxane-induced acute neuropathy | 75mg/day for 9 weeks | The percentage of patients achieving a 75% relief of pins-and-needles sensation was significantly greater in the VLX group (45.2% vs 0% in controls; P<.001). | No severe AEsReported AEs: nausea/vomiting, asthaenia/somnolence, dizziness, and insomnia |

AE: adverse event; bid: twice daily; NPRS: Numeric Pain Rating Scale; RCT: randomised clinical trial; VAS: visual analogue scale; VLX: venlafaxine.

Antidepressants are frequently used for the treatment of neuropathic pain,19 for several reasons: the analgesic effects of these drugs are faster than their antidepressant effects; antidepressants have been found to be efficacious in clinical trials of patients with pain and no associated depression and in clinical studies with animal models of different types of pain; some antidepressants are particularly effective for neuropathic pain (serotonin and norepinephrine are involved in the modulation of descending pain pathways); and chronic pain and depression share certain biochemical and anatomical mechanisms.20

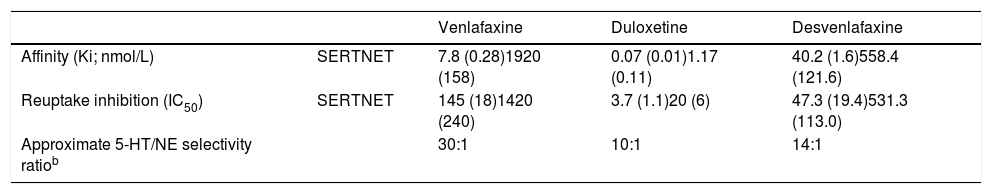

SNRIs have been shown to be useful for the treatment of neuropathic pain; their analgesic properties are thought to be explained by the inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake.19 SNRIs bind to serotonin and norepinephrine transporters (SERT and NET) to inhibit presynaptic serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, increasing the concentration of both neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft and in postsynaptic neurotransmission. Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition is sequential and dose-dependent, with inhibition of serotonin reuptake occurring first, followed by norepinephrine reuptake inhibition.21 The dose needed to affect levels of these neurotransmitters in vitro depends on the drug's relative binding affinity and selectivity for the transporters.22

Affinity is defined as a drug's or a ligand's capacity to bind to its receptor. The lower a given receptor's binding affinity to human transporters (Ki), the stronger a drug's binding affinity to the receptor, indicating greater activity of said neurotransmitter. The efficacy of a ligand in inhibiting a molecular target is measured with the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), which is the concentration required to achieve 50% response. The molecular target of SNRIs is inhibition of SERT and NET. The selectivity of an antidepressant is the ratio of the relative potency values for each target (SERT and NET in this case).23 The comparative affinities of SNRIs for SERT and NET are presented in Table 2. Venlafaxine presents 30 times greater affinity for reuptake inhibition of serotonin than for norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. A dose ≥ 150mg/day is required for inhibiting norepinephrine uptake. Doses greater than 300mg/day have been found to inhibit dopamine reuptake.23

Binding affinity of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitorsa.

| Venlafaxine | Duloxetine | Desvenlafaxine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity (Ki; nmol/L) | SERTNET | 7.8 (0.28)1920 (158) | 0.07 (0.01)1.17 (0.11) | 40.2 (1.6)558.4 (121.6) |

| Reuptake inhibition (IC50) | SERTNET | 145 (18)1420 (240) | 3.7 (1.1)20 (6) | 47.3 (19.4)531.3 (113.0) |

| Approximate 5-HT/NE selectivity ratiob | 30:1 | 10:1 | 14:1 |

5-HT: serotonin; IC50: half maximal inhibitory concentration; NE: norepinephrine; NET: norepinephrine transporter; SERT: serotonin transporter.

a Values are based on in vitro studies of human monoamine transporters.

b 5-HT/NE selectivity ratio: based on ratio of IC50 values.

Adapted from Raouf et al.23

The studies included in this review suggest that venlafaxine is effective for treating acute and chronic neuropathic pain. Richards et al.17 analysed the reasons why venlafaxine is not as effective for treating neuropathic pain secondary to spinal cord injury as it is for neuropathic pain associated with other conditions. In their study, patients with spinal cord injuries displayed abnormal spontaneous neuronal activity in the dorsal horn above and below the level of injury, which may explain why this type of pain responds better to agents that interact with the alpha-2-delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels, such as gabapentin and pregabalin. Therefore, differences in the pathophysiology of the underlying pain may explain the possible inefficacy of venlafaxine. However, most studies into venlafaxine's efficacy for treating neuropathic pain focus on peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes, such as diabetic neuropathy.17 In the other study reporting no improvement in pain with venlafaxine, Forssell et al.9 gave several possible explanations for the drug's lack of efficacy for atypical facial pain. The authors suggested that the dose used (75mg/day) may be too low, and that these patients may need higher doses (150-225mg/day). They also suggested that heterogeneity in the diagnosis of atypical facial pain may have led to misdiagnosis, given the lack of unified diagnostic criteria for this type of pain.9

In any case, venlafaxine was not found to be superior to other drugs. This stands in contrast with the results of the study by Jia et al.,12 who reported greater pain relief with venlafaxine than with carbamazepine. In the study by Razazian et al.,16 venlafaxine was found to be inferior to pregabalin in relieving neuropathic pain in patients with diabetic neuropathy: not only was it less efficacious, but it also caused significantly more adverse effects than carbamazepine and pregabalin, which led to a significantly greater drop-out rate (P=.01).

Sindrup et al.8 compared venlafaxine to imipramine in patients with diabetic neuropathy, observing no significant differences in efficacy between the 2 drugs. Although the number needed to treat was lower for imipramine (2.7 vs 5.2 for venlafaxine), the confidence interval was wide.

The studies in our review that compare venlafaxine against placebo demonstrate the analgesic potential of venlafaxine for neuropathic pain, and suggest that healthcare professionals involved in the management of neuropathic pain should consider the drug for treating these patients. However, venlafaxine has not been found to be superior to other agents.

A 2010 Cochrane review24 on the use of antidepressants for neuropathic pain concluded that venlafaxine was efficacious for treating neuropathic pain with a number needed to treat of 3.1 for at least moderate pain relief. The number needed to harm for major adverse events (events leading to patient drop-outs) was 16.2.

A more recent Cochrane review on the use of venlafaxine for neuropathic pain in adults, including only 6 double-blind RCTs, concluded that there is little evidence on the efficacy of venlafaxine for neuropathic pain and that some studies had a considerable risk of bias.25 Our review included a further 5 RCTs. Two of these concluded after the Cochrane review was published,16,17 and another was an open-label trial13 (the Cochrane review only included blinded RCTs).

The studies included in our review present several limitations. First, some studies include relatively small samples. Second, selection criteria varied between studies: although all the patients included had neuropathic pain, the differences in the type of neuropathic pain may have had an impact on results. The studies included also followed different research methodologies and used different pain assessment scales. They also used different doses of the drug, which may have had an impact on results; therefore, no conclusive evidence can be drawn from these results. Furthermore, treatment and follow-up times also varied between studies. Lastly, the available evidence on the topic is relatively limited, with only 13 studies and few empirical data.

In conclusion, while venlafaxine is not currently indicated for neuropathic pain, it has been found to be safe and well tolerated as a symptomatic treatment in these patients. The available evidence supports the efficacy of the drug (especially at doses of at least 150mg/day), although further research is needed, particularly comparing the drug against other pharmacological agents.

Please cite this article as: Alcántara Montero A, González Curado A. ¿Existe evidencia científica para el empleo de venlafaxina en dolor neuropático? Neurología. 2020;35:522–530.