Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an infrequent, acquired disorder, in which impaired biosynthesis and defective surface expression in blood cells of various glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane proteins, such as complement inhibitors CD55 and CD59, can lead to complement-mediated hemolysis. This in turn can result in smooth muscle dystonias, thrombosis, and, in some cases, bone marrow failure. Clinical manifestations in PNH occur as a consequence of clonal expansion of haematopoietic stem cells deficient in GPI-anchored proteins due to somatic mutations in PIGA.1 The affected erythrocytes are more susceptible to complement attack, triggering lysis. However, GPI-deficient platelets and granulocytes are likely to be behind the thrombotic risk.2

Clinical symptoms include weakness and fatigue on exertion, dyspnea, abdominal pain, and chest pain. These can be accompanied by hemoglobinuria, Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, pulmonary hypertension, renal impairment, and, ultimately, death.3

Thrombotic events are the most serious complication associated with PNH and typically occur in unusual sites, such as dermal, mesenteric, hepatic, portal, splenic, and renal veins. Brain involvement is rare and usually manifests as cerebral venous thrombosis or chronic small vessel disease, defined by silent periventricular and deep white matter lesions, multiple lacunar infarcts and/or microbleeds.4 Arterial events, especially in coronary arteries, occur mostly in young patients.5 Involvement of intracranial and extracranial arterial sites is unusual, but when it occurs, middle cerebral arteries are the most commonly affected.6 Moyamoya syndrome is rarely described in medical literature.7

We report the case of a young man with a medical history of Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia who had an ischemic stroke accompanied by steno-occlusive changes in intracranial arteries.

Case presentationA 41-year-old mestizo male patient was transferred to our hospital from another medical center, where he had been previously hospitalized for approximately 15 days because of acute right upper weakness, facial palsy, and dysarthria of sudden onset, without headache or other neurovegetative symptoms. Due to the time between onset of symptoms and delayed arrival at our institution, he was not considered a candidate for fibrinolytic therapy. He had a medical history of anemia, which had not been studied, and had once needed a red blood cell transfusion.

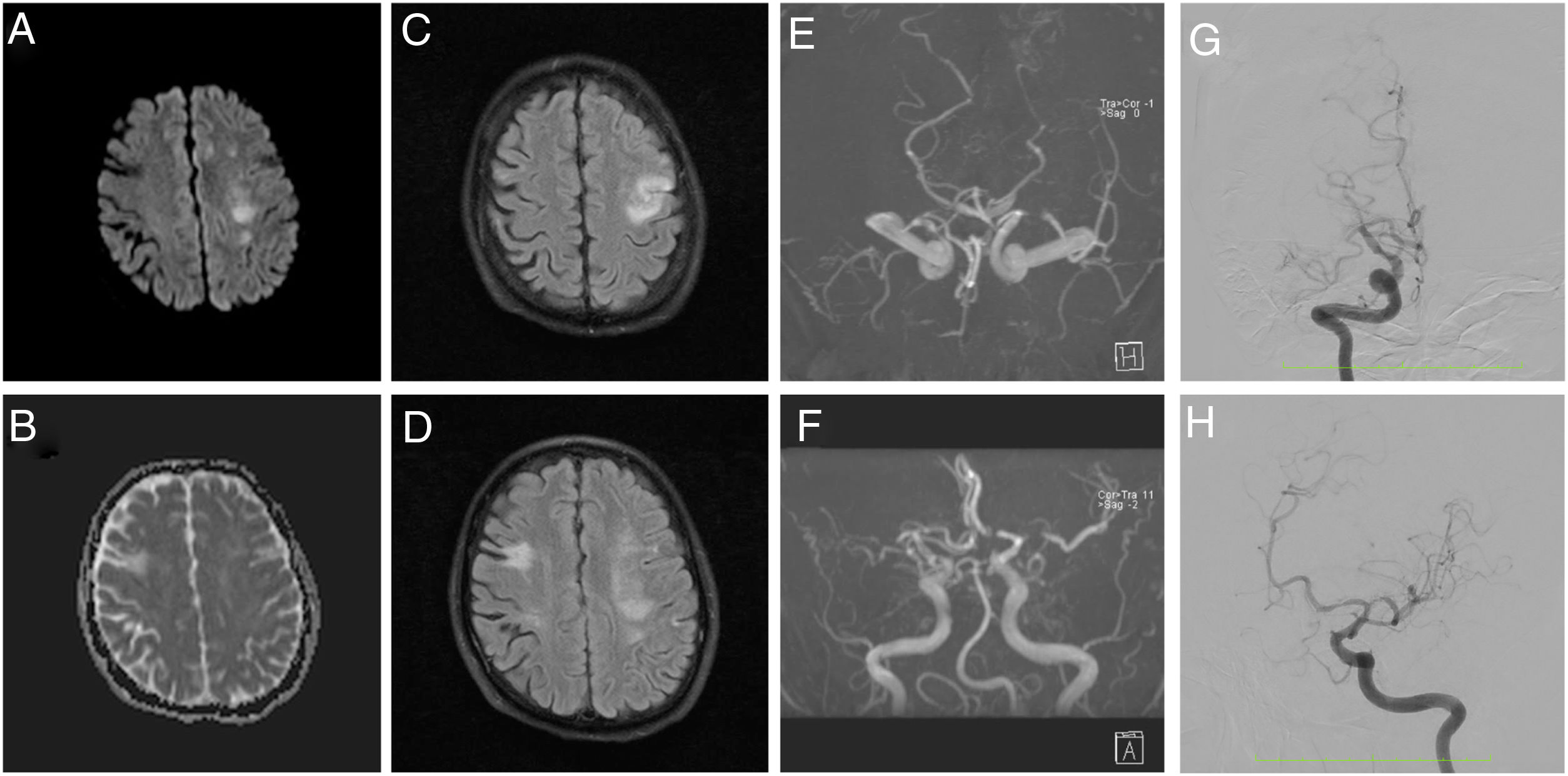

Brain magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) evidenced a subacute ischemic stroke consistent with presenting symptoms, chronic bilateral ischemic events, and altered blood flow in MCAs. Cerebral angiography showed multiple steno-occlusive changes in the proximal portion of both internal carotid arteries, with occlusion of the right M1 segment and significant stenosis at the origin of the left M1 segment, stenosis at the origin of the left P1 segment, and collateral flow arising from the right anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and supplying the territory corresponding to the posterior division of the right MCA, suggestive an intracranial arteriopathy (Fig. 1). Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was normal, as well as chest computerized tomography angiography and transthoracic echocardiography.

MRA diffusion weighted (A), apparent diffusion coefficient (B), FLAIR (C and D), and time of flight (E and F) images show a subacute ischemic stroke in left MCA territory, chronic ischemic events, and remarkably decreased blood flow in MCAs. Angiography (G and H) shows 60% stenosis of the proximal portion of the right ICA, complete occlusion of the right M1 segment, 70% stenosis of the left M1 segment, 50% stenosis of the left P1 segment, and collateral flow from the right ACA irrigating the territory corresponding to the posterior division of the right MCA.

Haematologic findings included Coombs negative hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin value of 6.6g/dl, 4080leukocytes/mm3, 288000platelets/mm3, a normal peripheral blood smear, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, increased indirect bilirubin, increased reticulocyte count, and decreased haptoglobin. Serum chemistries and autoimmunity screening tests were normal.

Due to the finding of hemolytic anemia in a patient presenting with ischemic stroke, having excluded immune and microangiopathic causes of hemolysis, flow cytometry/FLAER was performed. It detected CD59 deficiency in 50% of erythrocytes, CD16 and CD24 deficiency in 88% of neutrophils, CD24 deficiency in 94.5% of eosinophils, and CD14 deficiency in 91% of monocytes, consistent with defective clones immunophenotypically compatible with PNH.

The patient was diagnosed with classical PNH associated with typical features of Moyamoya syndrome and referred to hematology for subsequent ambulatory follow-up. The patient was approved for initiation of immunotherapy with eculizumab 2 months after discharge. At the 3-month follow-up, he persisted with right upper extremity paresis, mild dysarthria, and speech apraxia, but without evidence of new episodes of hemolysis, thromboembolic events, or acute stroke.

DiscussionHematological disorders are an unusual cause of cerebrovascular disease but have been increasingly recognized as the most frequent cause of cerebral infarcts of unusual etiology. They have been identified as the underlying cause in 1.3% of cases of acute stroke and 1% of hemorrhagic strokes. In young adults, approximately 1% of cases of cerebral infarction and 4% of cases of cerebrovascular disease have been estimated to be caused by these conditions. The importance of identifying a hematological disorder as the etiology of stroke lies not only in its impact on the choice of treatment and secondary prevention of acute cerebrovascular disease, but also in the opportunity to potentially improve prognosis and prevent complications associated with the underlying condition.8

Thromboembolic events, which are venous in 85% of cases and arterial in 15% of cases, are the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in PNH, accounting for 40–67% of deaths before complement inhibition therapy was introduced. 20.5% of patients have simultaneous multi-site involvement, 16–40% of patients have presented an event before diagnosis, and 29.44% have presented at least one event through the course of the disease.2 Cerebral venous thrombosis is the second most frequent location of venous thrombosis, following hepatic veins, and occurs in 2–8% of PHN patients.3 Moyamoya angiopathy (MMA) is an intracranial phenomenon which is characterized by bilateral progressive steno-occlusive changes in the intracranial portion of the ICAs and their terminal bifurcation, as well as the proximal portion of the ACAs and/or MCAs, with compensatory collateral vascularization. It represents a nonspecific response to an impairment of arterial flow and carries a risk of hemodynamic and embolic transient ischemic attacks and stroke.9

Moyamoya syndrome (MMS) has been reported in multiple conditions, such as meningitis, type 1 neurofibromatosis, trisomy 21, cranial irradiation, cerebrovascular atherosclerosis, cerebral vasculitis and different types of anemias, particularly hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell disease, thalassemia, Fanconi's anemia, and iron deficiency anemia). Changes are usually bilateral and not associated with arteritis. Recently, posterior cerebral artery and vertebro-basilar involvement have been recognized.7,9 The pathophysiology behind PHN–Moyamoya syndrome is unclear and involves both hemolytic and non-hemolytic mechanisms.10 It has been suggested that cerebral events are a consequence of the lack of CD59 on the cerebral endothelium, which can lead to disruption by the complement system, and dysregulation of signaling between the complement and hemostasis systems (platelets, coagulation and fibrinolytic systems). Additionally, the improvement of disease-associated symptoms and findings on brain imaging with eculizumab alone supports an immune escape theory or “second hit” theory, in which autoimmune T lymphocytes attack GPI-positive hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), while GPI-deficient HSC escape.1

Therapeutic strategies consist of indefinite anticoagulation, folic acid supplementation, iron replacement, blood transfusions, and corticosteroids during the active hemolytic process. Additionally, the use of eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody which binds to complement protein C5 and prevents the formation of the membrane attack complex, should be considered. It has been shown to increase health-related quality of life and transfusion independence, and can decrease LDH levels.1

ConclusionPNH should be taken into account as a potential cause of ischemic stroke, especially in young patients presenting with Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia. Because MMS is a potential complication of PNH, intracranial vessels should be regularly assessed in these patients. Early recognition of this disease or other hematological disorders that may result in stroke can lead to early initiation of appropriate therapy which can have a positive impact on quality of life and prevent new thrombotic events.

Informed consentWritten informed consent was provided by the patient. The case report received approval from the ethics committee.

Conflict of interestNone.

Department and institution where work was performed: Department of Neurology at Instituto Neurológico de Colombia in Medellín, Colombia.