Bilateral facial paralysis is a clinical entity that may be caused by a wide range of processes, including infection, autoimmune diseases, toxic diseases, tumours, and metabolic diseases affecting the peripheral facial nerve.1,2 Very few cases have been described of WEBINO (wall-eyed bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia) syndrome associated with facial diplegia. We present the case of a patient with complete facial diplegia of central origin secondary to brainstem ischaemia, who also presented WEBINO syndrome.

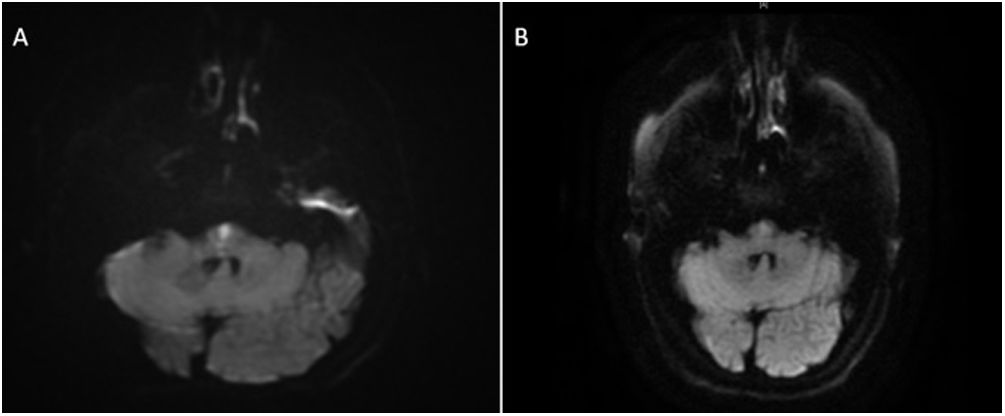

The patient was a 66-year-old man who consulted due to 4 days’ progression of instability and oculomotor alterations, of sudden onset. The examination revealed bilateral adduction impairment, contralateral abduction nystagmus, and primary gaze exotropia, with preserved convergence. Due to suspicion of acute bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia, the patient was admitted for further study. An MRI study (Fig. 1) revealed a lacunar infarction in the lower paramedian pons; the patient received dual antiplatelet therapy and was discharged.

Seven days later he consulted due to bilateral peripheral facial paralysis and dysarthria. The physical examination revealed facial diplegia and bilateral Bell’s phenomenon (Fig. 2), as well as WEBINO syndrome, without involvement of other cranial nerves or paresis of the limbs; deep tendon reflexes were preserved. Blood tests (autoimmunity, serology, and total protein tests), CSF analysis (no albuminocytologic dissociation), and electroneurography of the limbs yielded normal results. The blink reflex revealed axonal neuropathy of both facial nerves, with involvement of the trigeminofacial reflex arc. A subsequent MRI study (Fig. 1) revealed decreased signal intensity of the paramedian pontine stroke on T2-FLAIR and DWI sequences, linked to the subacute progression of the infarction.

Physical examination. A) Physical examination performed during the patient’s second hospitalisation, showing bilateral facial paralysis affecting both the upper and lower face. B) Physical examination performed by the rehabilitation department one month after discharge, showing persistent right lower facial paresis.

The patient improved during hospitalisation, regaining the ability to partially close both eyes. We hypothesise that nuclear involvement is the most probable cause for our patient’s facial diplegia. At 3 months, facial diplegia had improved substantially, but right internuclear ophthalmoplegia and mild right lower facial paresis persisted (Fig. 2).

Bilateral facial paralysis is a rare clinical entity, with an approximate incidence of one case per 5 million population. It is usually of peripheral origin; its aetiology is therefore highly heterogeneous, as it is linked to cranial mononeuropathy multiplex. Causes include infections, immune-mediated and metabolic diseases, toxic processes, tumours, and trauma.1,2 Vascular involvement of central nuclei (pseudoperipheral) has been reported as a cause of unilateral, and more rarely bilateral, paralysis, usually in association with other manifestations of brainstem involvement.3,4

The reported cases of pseudoperipheral facial paralysis of vascular origin are caused by ischaemic lesions to the pontine tegmentum.5 Tegmental infarctions represent only a small percentage of all cases of pontine infarction. They are characterised by the anatomical association between the fascicles of the facial nerve and the structures involved in horizontal gaze, including the abducens nucleus and the medial longitudinal fasciculus.4,6 This explains the rare cases of facial diplegia of vascular origin associated with one-and-a-half syndrome or gaze palsy manifesting as WEBINO syndrome.4

In patients with isolated pontine infarctions, progressive deficits following ischaemic stroke seem to be relatively common, as in the case reported here. Their frequency varies greatly (10%–60%), probably due to the heterogeneity of the criteria applied.7,8

In our case, the presence of progressive symptoms and complete facial diplegia made us reconsider the hypothesis of vascular aetiology. In general terms, the diagnostic assessment must include a blood analysis, with complete blood count, glucose concentration, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serology tests, and autoimmune study. CSF analysis and MRI studies should also be performed.1

In our case, complementary studies seeking to detect a possible peripheral cause of cranial mononeuropathy yielded negative results, and the progression of our patient’s symptoms also ruled out this hypothesis. Neuroimaging studies did not show an increase in infarct volume that may explain the clinical worsening; this led us to hypothesise that the underlying mechanism may be cytotoxic, which may also explain the rapid improvement of our patient’s symptoms.

Our case shows that facial diplegia with upper and lower involvement may occasionally be secondary to an ischaemic lesion involving the facial nerve nucleus in the brainstem, even in the absence of the typical chronology of vascular events. However, this aetiology of bilateral facial nerve involvement is extremely rare, and thorough complementary testing should be performed to rule out other more frequent causes.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.