Music therapy is one of the types of active ageing programmes which are offered to elderly people. The usefulness of this programme in the field of dementia is beginning to be recognised by the scientific community, since studies have reported physical, cognitive, and psychological benefits. Further studies detailing the changes resulting from the use of music therapy with Alzheimer patients are needed.

ObjectivesTo determine the clinical improvement profile of Alzheimer patients who have undergone music therapy.

Patients and methodsForty-two patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease (AD) underwent music therapy for 6 weeks. The changes in results on the Mini-Mental State Examination, Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Barthel Index scores were studied. We also analysed whether or not these changes were influenced by the degree of dementia severity.

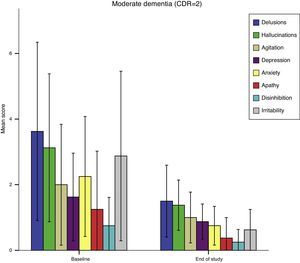

ResultsSignificant improvement was observed in memory, orientation, depression and anxiety (HAD scale) in both mild and moderate cases; in anxiety (NPI scale) in mild cases; and in delirium, hallucinations, agitation, irritability, and language disorders in the group with moderate AD. The effect on cognitive measures was appreciable after only 4 music therapy sessions.

ConclusionsIn the sample studied, music therapy improved some cognitive, psychological, and behavioural alterations in patients with AD. Combining music therapy with dance therapy to improve motor and functional impairment would be an interesting line of research.

La musicoterapia forma parte de los programas de envejecimiento activo que se ofrecen a las personas mayores. Su utilidad en el campo de las demencias empieza a ser valorada por la comunidad científica, ya que se han reportado efectos positivos a nivel físico, cognitivo y psicológico. Son necesarios más estudios que perfilen el alcance de tales cambios en la enfermedad de Alzheimer.

ObjetivosConocer el perfil de mejoría clínica que experimentan los pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer con la aplicación de una intervención de musicoterapia.

Pacientes y métodosSe aplicó un tratamiento con musicoterapia durante 6 semanas a 42 pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer en estadio leve-moderado. Se estudiaron los cambios en las puntuaciones de Mini-examen del estado mental, Inventario de síntomas neuropsiquiátricos, Escala hospitalaria de ansiedad y depresión, e índice de Barthel. Se estudió si estos cambios se influían por el grado de severidad de la demencia.

ResultadosSe observó una mejoría significativa de memoria, orientación, depresión y ansiedad (escala HAD) en pacientes leves y moderados; de ansiedad (escala NPI) en pacientes leves; de los delirios, alucinaciones, agitación, irritabilidad y trastornos del lenguaje en el grupo con demencia moderada. El efecto sobre las medidas cognitivas es ya apreciable a las 4 sesiones de musicoterapia.

ConclusionesEn la muestra estudiada, la musicoterapia mejoró algunas alteraciones cognitivas, psicológicas y conductuales de los pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Sería interesante complementar la musicoterapia con intervenciones de danzaterapia a fin de mejorar los aspectos motores y funcionales.

The prevalence of dementia is increasing worldwide.1 With this in mind, and since dementia requires a substantial share of the total healthcare and social resources, it is recognised as a priority in research. The most frequent cause of dementia in developed countries is Alzheimer disease (AD).2 Current research aims to halt cognitive decline through pharmacological treatment.3 Anticholinesterase drugs and memantine have demonstrated moderate effects on cognitive function. These drugs are effective for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms only at high doses and do not work in some cases.4 These symptoms are usually treated with neuroleptic and anxiolytic drugs, which worsen motor function and result in premature death.5 Non-pharmacological treatment provides a promising alternative for improving behaviour and cognitive function.6–8 One such intervention is music therapy, which uses music to improve communication, learning, mobility, and other mental and physical functions.9 Numerous music therapy techniques have been developed.9 Active techniques are based on direct interaction with the patient, whereas receptive techniques require a lower level of participation. Interventions may be tailored to a specific subject and carried out with individuals or in groups. In patients with dementia, music therapy has been shown to improve neuropsychiatric symptoms and, to a lesser extent, cognitive function.10,11 However, we have yet to determine the symptoms most likely to improve with music therapy and whether clinical improvement depends on the stage of the disease. Our study included patients with AD, who were classified in 2 groups according to disease severity (mild or moderate). Our purpose was to determine whether music therapy can improve patients’ cognitive function, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and functional capacity and, if so, to evaluate whether these changes depend on dementia severity.

Patients and methodsPatientsWe selected patients from 2 geriatric residences in the Region of Murcia and included those who met the diagnostic criteria for probable AD proposed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders,12 in a mild or moderate stage according to the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale.13 We excluded deaf or aphasic patients who might have difficulty understanding instructions during the intervention. Patients and their relatives and carers at the geriatric residences signed informed consent forms prior to inclusion in the study. The study was approved by the ethics committee at Universidad de Murcia.

MeasuresQuestionnaire of musical preferences.14 This tool gathers data on patients’ musical preferences. It enquires about patients’ favourite instruments and musical genres as well as about their dislikes.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).15 This quick-to-administer questionnaire evaluates orientation in time and place, attention, verbal memory, language, and motor skills. Total scores range from 0 to 30 points (orientation [0-10], memory [0-6], attention [0-5], and language–motor skills [0-9]).

Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).16 This tool assesses 10 domains of behavioural function: delusions, hallucinations, depression, agitation, irritability, aberrant motor behaviour, anxiety, aggressiveness, apathy, and disinhibition. Frequency of each of these symptoms is scored on a 4-point scale whereas severity is scored on a 3-point scale.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).17 This 14-item questionnaire includes 2 subscales containing 7 items each (anxiety and depression). Frequency of each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0-3); each subscale is scored from 0 to 21 points, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Barthel Index (BI).18 This is a useful tool for evaluating patients’ ability to complete 10 basic activities of daily living (feeding, bathing, grooming, dressing, bowels, bladder, toilet use, transfers, mobility, and stairs). Scores range from 0 (completely dependent) to 100 (independent).

ProcedureOur patients underwent cognitive, neuropsychiatric, and functional assessment; the MMSE, NPI, and HADS were administered by a neurologist specialising in dementia and the BI was given by an occupational therapist. In each geriatric residence, participants were divided in 2 groups (fewer than 12 patients per group). Musical preferences were subsequently analysed using the questionnaire on musical preferences; our purpose was to choose songs that most of the participants would like and rule out music genres that they would regard as unpleasant. Patients did not use headphones; rather, music was played on a high-quality stereo system with the speakers placed in the room in such a way as to avoid echo. Patients attended 2 weekly sessions of music therapy lasting 45min. Each session included several activities: welcome song (in which patients greeted each other and introduced themselves), rhythmic accompaniment by clapping hands or playing music instruments (triangle, tambourine, maracas), moving to background music (patients were instructed to move their arms and legs to rhythm of a song, including dance therapy with hoops and balls once a week), guessing songs and interpreters (music bingo, plus playing name-that-tune using drawings once a week), and farewell song (in which patients said goodbye). Sessions were designed and led by 2 music therapists. The rooms in which sessions took place were large enough for patients to be comfortable yet focused on the task (40-48m2). Rooms were sound-proof, well-lit, and far from any sources of noise or distress; they had wooden floors and thermal insulation to ensure a pleasant temperature.

Patients underwent cognitive, neuropsychiatric, and functional assessment after 3 weeks (6 sessions) and at the end of the study period (12 sessions). Tests were administered by the same professionals as at baseline. Statistical analysis was performed by a professional blinded to patient data (mild/moderate AD), and to time-related data (baseline/follow-up/end-of-study assessment).

Statistical analysisWe used repeated measures ANOVA to evaluate changes in outcome variables throughout the intervention period; effect size was estimated with the partial η2 coefficient. We tested for normality and sphericity of the variance matrix before conducting repeated measures ANOVA. When sphericity was violated, a correction factor (epsilon) was applied to the F-value. For those symptoms responding to music therapy, we analysed whether the effect was present in both groups (paired samples t test). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.

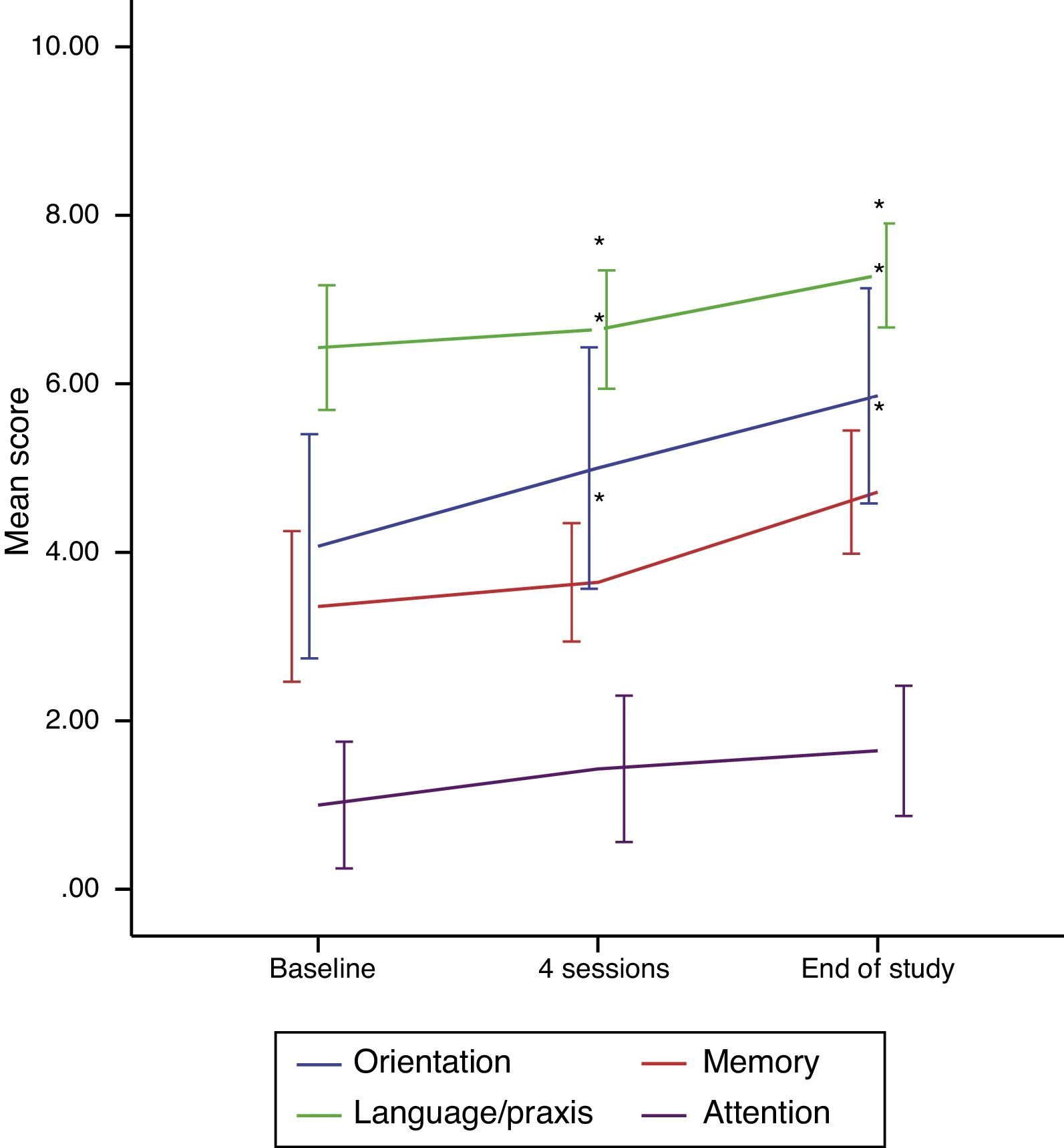

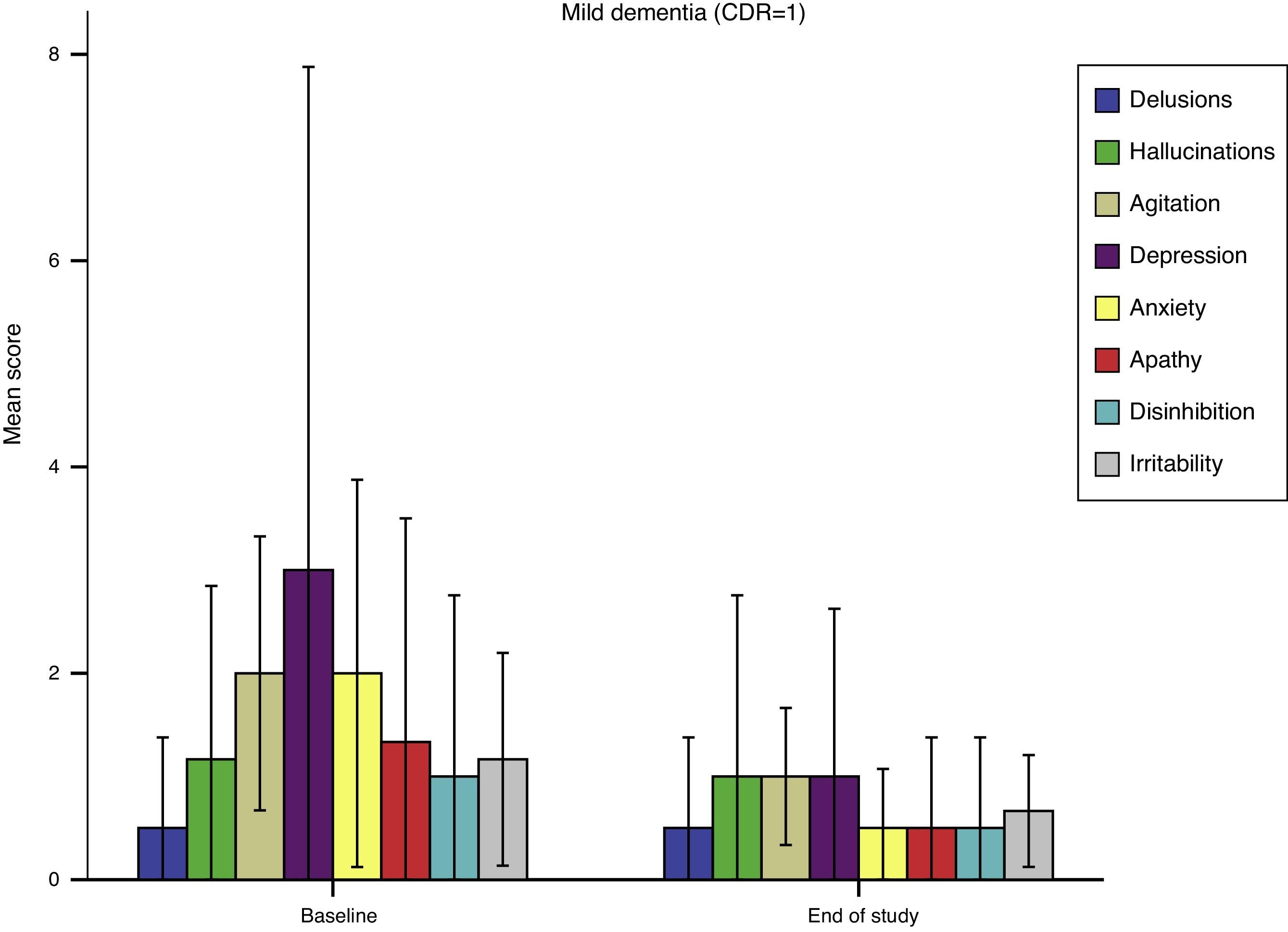

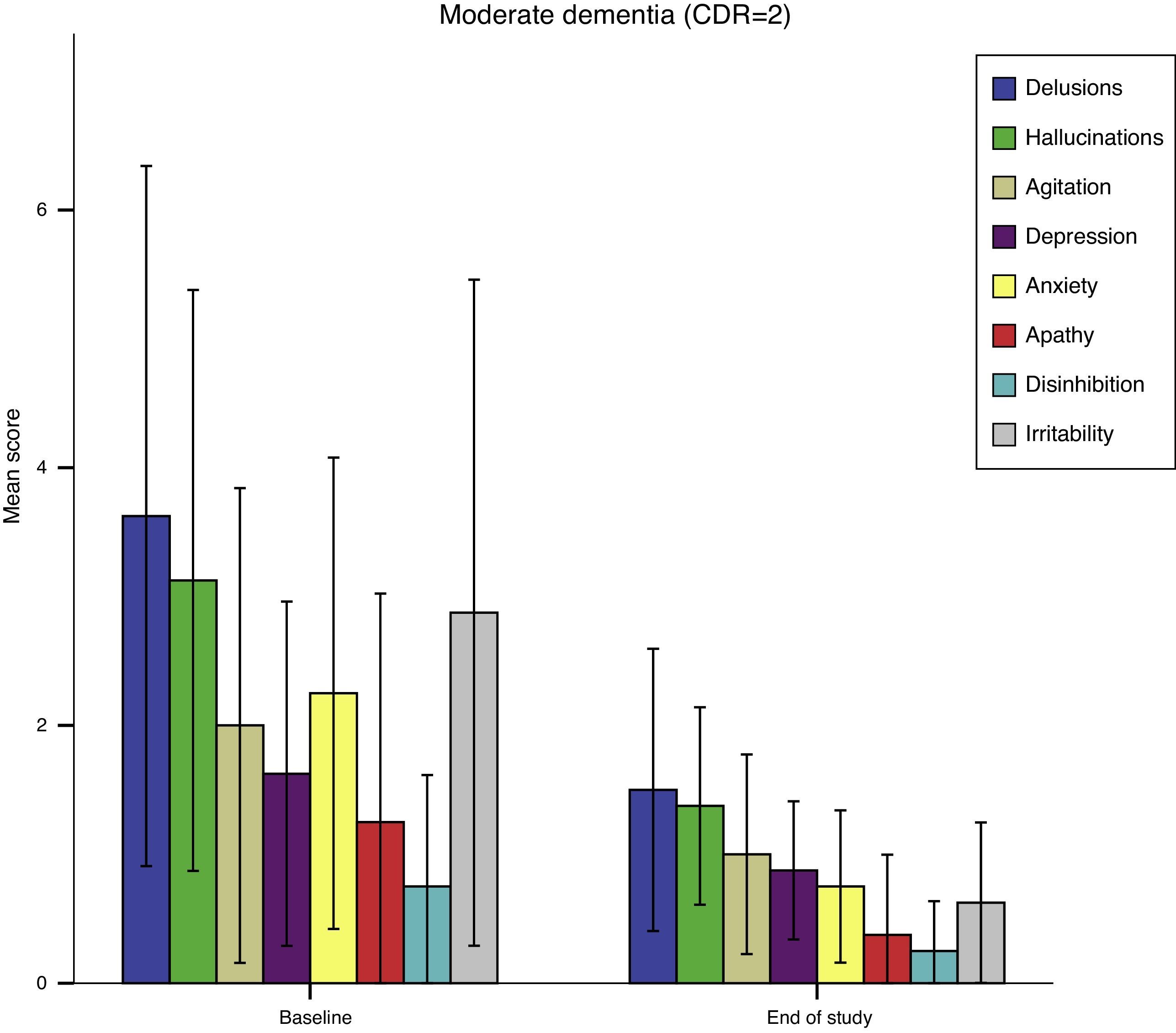

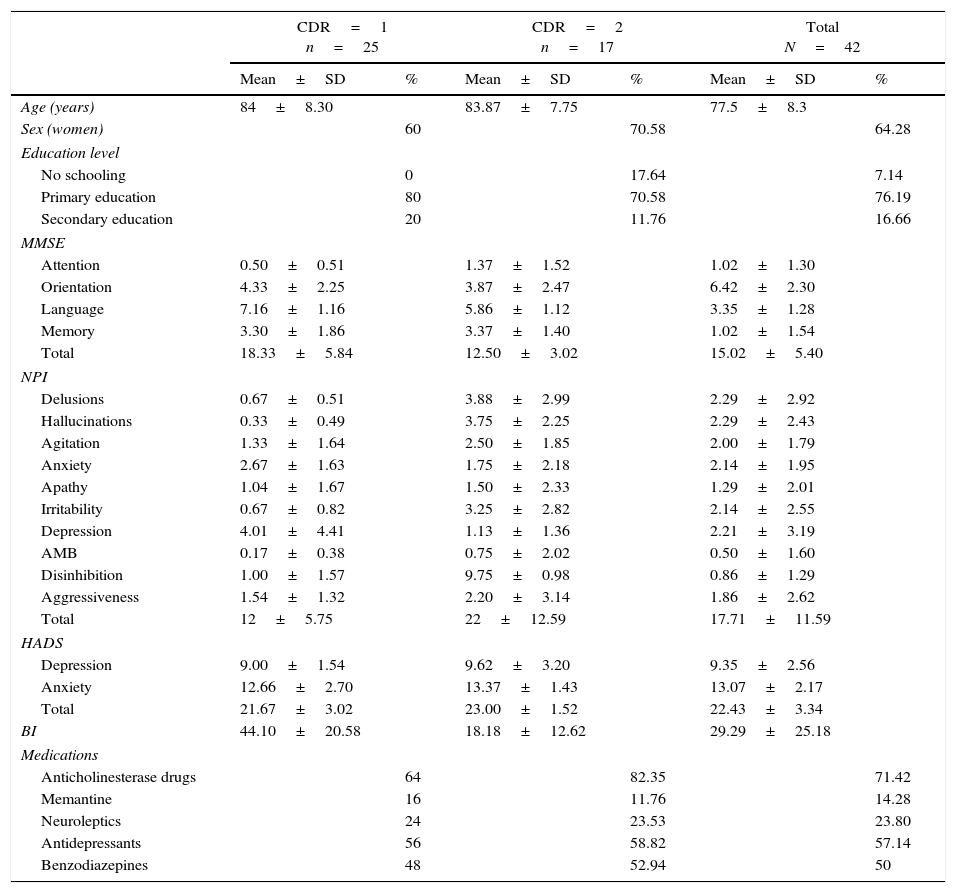

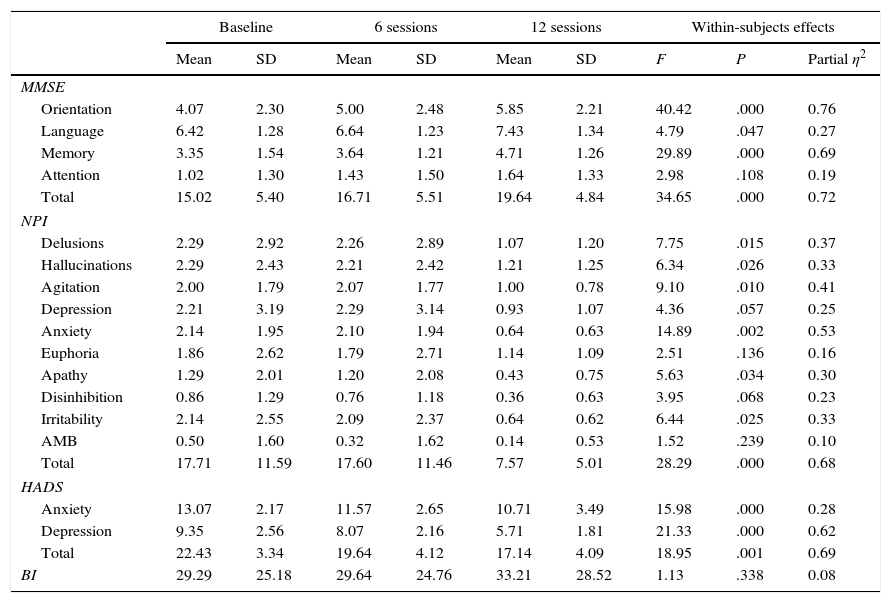

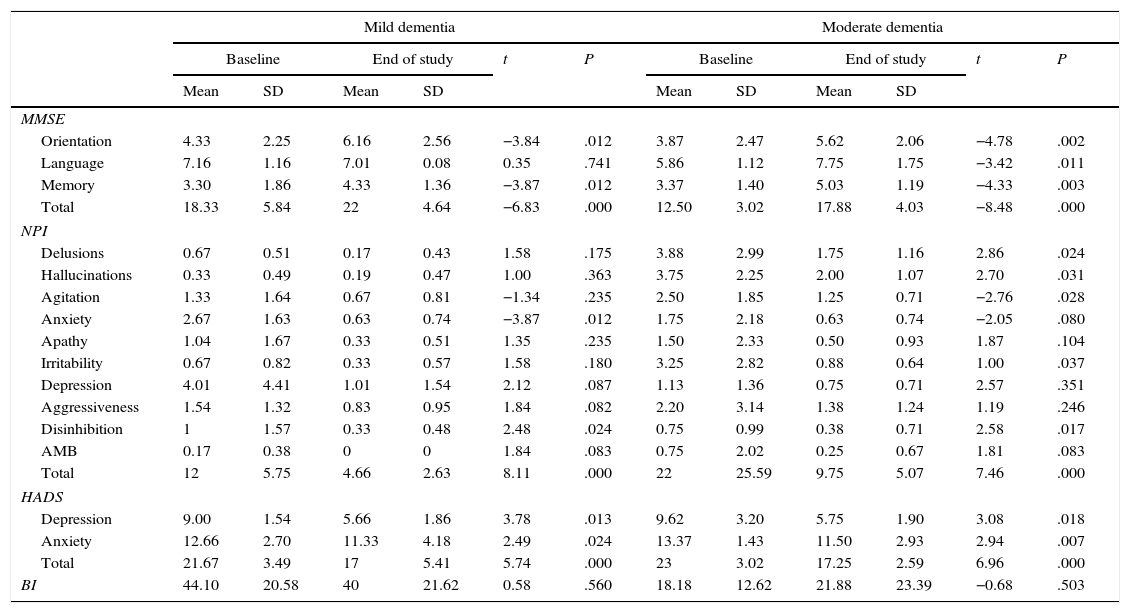

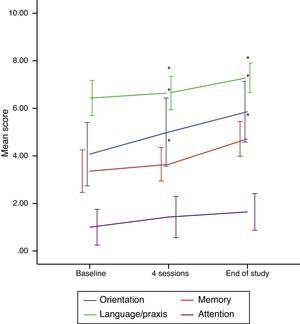

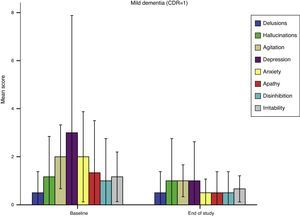

ResultsOur sample included 42 patients (27 women) with a mean age of 77.5±8.3 years. Dementia was mild in 25 patients (CDR=1) and moderate in 17 (CDR=2). Regarding our patients’ education level, 3 had no schooling, 32 had completed primary school, and 7 had finished secondary school. The most frequent comorbidities were bone diseases (83.33%), heart diseases (21.42% heart failure and 14.28% ischaemic heart disease), endocrine and metabolic disorders (71.42% arterial hypertension, 33.33% diabetes mellitus, and 52.38% dyslipidaemia), and 28.57% chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for our sample, including drugs for AD. No significant differences in drug use were found between groups (CDR1 and CDR2) (P>.1). Table 2 shows the results of the repeated measures ANOVA. Music therapy significantly increased MMSE scores, especially in the domains of orientation, language, and memory. Effect size was large for orientation and memory. Cognitive function improved progressively throughout the study period (Fig. 1). Regarding language, differences were significant only between baseline and final scores (P=.047). We observed a marked decrease in total NPI scores, with scores decreasing in most of the domains (Table 2). However, decreases between baseline and follow-up scores were not significant for any of the symptoms assessed with the NPI (P>.05 for all symptoms). Scores on the anxiety and depression subscales of the HADS improved; the effect size was large in the latter case. Depression did not improve after 6 sessions (P>.05). Music therapy had no significant effects on BI scores (P=.338). Significant differences were also detected in total MMSE scores and in the domains of memory and orientation between groups CDR1 and CDR2 (Table 3). Only the group with moderate dementia displayed significant improvements in language. Regarding neuropsychiatric symptoms, delusions, hallucinations, irritability, and agitation improved significantly in the group with moderate dementia (Table 3). Patients in the CDR2 group displayed higher baseline scores in the domains of delusions, hallucinations, and irritability than did those in the CDR1 group (P<.005); the effect on disinhibition was significant in both groups. According to HADS scores, music therapy had a positive effect on anxiety and depression in both groups. Anxiety as measured on the NPI improved significantly in the mild dementia group; improvements were less marked in the group with moderate dementia (P=.080). Depression did not improve significantly in patients with moderate dementia and lessened only slightly in those with mild dementia (P=.087) (Figs. 2 and 3).

Descriptive statistics for our sample.

| CDR=1 n=25 | CDR=2 n=17 | Total N=42 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | % | Mean±SD | % | Mean±SD | % | |

| Age (years) | 84±8.30 | 83.87±7.75 | 77.5±8.3 | |||

| Sex (women) | 60 | 70.58 | 64.28 | |||

| Education level | ||||||

| No schooling | 0 | 17.64 | 7.14 | |||

| Primary education | 80 | 70.58 | 76.19 | |||

| Secondary education | 20 | 11.76 | 16.66 | |||

| MMSE | ||||||

| Attention | 0.50±0.51 | 1.37±1.52 | 1.02±1.30 | |||

| Orientation | 4.33±2.25 | 3.87±2.47 | 6.42±2.30 | |||

| Language | 7.16±1.16 | 5.86±1.12 | 3.35±1.28 | |||

| Memory | 3.30±1.86 | 3.37±1.40 | 1.02±1.54 | |||

| Total | 18.33±5.84 | 12.50±3.02 | 15.02±5.40 | |||

| NPI | ||||||

| Delusions | 0.67±0.51 | 3.88±2.99 | 2.29±2.92 | |||

| Hallucinations | 0.33±0.49 | 3.75±2.25 | 2.29±2.43 | |||

| Agitation | 1.33±1.64 | 2.50±1.85 | 2.00±1.79 | |||

| Anxiety | 2.67±1.63 | 1.75±2.18 | 2.14±1.95 | |||

| Apathy | 1.04±1.67 | 1.50±2.33 | 1.29±2.01 | |||

| Irritability | 0.67±0.82 | 3.25±2.82 | 2.14±2.55 | |||

| Depression | 4.01±4.41 | 1.13±1.36 | 2.21±3.19 | |||

| AMB | 0.17±0.38 | 0.75±2.02 | 0.50±1.60 | |||

| Disinhibition | 1.00±1.57 | 9.75±0.98 | 0.86±1.29 | |||

| Aggressiveness | 1.54±1.32 | 2.20±3.14 | 1.86±2.62 | |||

| Total | 12±5.75 | 22±12.59 | 17.71±11.59 | |||

| HADS | ||||||

| Depression | 9.00±1.54 | 9.62±3.20 | 9.35±2.56 | |||

| Anxiety | 12.66±2.70 | 13.37±1.43 | 13.07±2.17 | |||

| Total | 21.67±3.02 | 23.00±1.52 | 22.43±3.34 | |||

| BI | 44.10±20.58 | 18.18±12.62 | 29.29±25.18 | |||

| Medications | ||||||

| Anticholinesterase drugs | 64 | 82.35 | 71.42 | |||

| Memantine | 16 | 11.76 | 14.28 | |||

| Neuroleptics | 24 | 23.53 | 23.80 | |||

| Antidepressants | 56 | 58.82 | 57.14 | |||

| Benzodiazepines | 48 | 52.94 | 50 | |||

AMB: aberrant motor behaviour; SD: standard deviation; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; BI: Barthel Index; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Changes in scores after 6 and 12 sessions of music therapy (repeated measures ANOVA).

| Baseline | 6 sessions | 12 sessions | Within-subjects effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | P | Partial η2 | |

| MMSE | |||||||||

| Orientation | 4.07 | 2.30 | 5.00 | 2.48 | 5.85 | 2.21 | 40.42 | .000 | 0.76 |

| Language | 6.42 | 1.28 | 6.64 | 1.23 | 7.43 | 1.34 | 4.79 | .047 | 0.27 |

| Memory | 3.35 | 1.54 | 3.64 | 1.21 | 4.71 | 1.26 | 29.89 | .000 | 0.69 |

| Attention | 1.02 | 1.30 | 1.43 | 1.50 | 1.64 | 1.33 | 2.98 | .108 | 0.19 |

| Total | 15.02 | 5.40 | 16.71 | 5.51 | 19.64 | 4.84 | 34.65 | .000 | 0.72 |

| NPI | |||||||||

| Delusions | 2.29 | 2.92 | 2.26 | 2.89 | 1.07 | 1.20 | 7.75 | .015 | 0.37 |

| Hallucinations | 2.29 | 2.43 | 2.21 | 2.42 | 1.21 | 1.25 | 6.34 | .026 | 0.33 |

| Agitation | 2.00 | 1.79 | 2.07 | 1.77 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 9.10 | .010 | 0.41 |

| Depression | 2.21 | 3.19 | 2.29 | 3.14 | 0.93 | 1.07 | 4.36 | .057 | 0.25 |

| Anxiety | 2.14 | 1.95 | 2.10 | 1.94 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 14.89 | .002 | 0.53 |

| Euphoria | 1.86 | 2.62 | 1.79 | 2.71 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 2.51 | .136 | 0.16 |

| Apathy | 1.29 | 2.01 | 1.20 | 2.08 | 0.43 | 0.75 | 5.63 | .034 | 0.30 |

| Disinhibition | 0.86 | 1.29 | 0.76 | 1.18 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 3.95 | .068 | 0.23 |

| Irritability | 2.14 | 2.55 | 2.09 | 2.37 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 6.44 | .025 | 0.33 |

| AMB | 0.50 | 1.60 | 0.32 | 1.62 | 0.14 | 0.53 | 1.52 | .239 | 0.10 |

| Total | 17.71 | 11.59 | 17.60 | 11.46 | 7.57 | 5.01 | 28.29 | .000 | 0.68 |

| HADS | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 13.07 | 2.17 | 11.57 | 2.65 | 10.71 | 3.49 | 15.98 | .000 | 0.28 |

| Depression | 9.35 | 2.56 | 8.07 | 2.16 | 5.71 | 1.81 | 21.33 | .000 | 0.62 |

| Total | 22.43 | 3.34 | 19.64 | 4.12 | 17.14 | 4.09 | 18.95 | .001 | 0.69 |

| BI | 29.29 | 25.18 | 29.64 | 24.76 | 33.21 | 28.52 | 1.13 | .338 | 0.08 |

AMB: aberrant motor behaviour; SD: standard deviation; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; BI: Barthel Index; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Changes in scores by disease severity.

| Mild dementia | Moderate dementia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of study | t | P | Baseline | End of study | t | P | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| MMSE | ||||||||||||

| Orientation | 4.33 | 2.25 | 6.16 | 2.56 | −3.84 | .012 | 3.87 | 2.47 | 5.62 | 2.06 | −4.78 | .002 |

| Language | 7.16 | 1.16 | 7.01 | 0.08 | 0.35 | .741 | 5.86 | 1.12 | 7.75 | 1.75 | −3.42 | .011 |

| Memory | 3.30 | 1.86 | 4.33 | 1.36 | −3.87 | .012 | 3.37 | 1.40 | 5.03 | 1.19 | −4.33 | .003 |

| Total | 18.33 | 5.84 | 22 | 4.64 | −6.83 | .000 | 12.50 | 3.02 | 17.88 | 4.03 | −8.48 | .000 |

| NPI | ||||||||||||

| Delusions | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 0.43 | 1.58 | .175 | 3.88 | 2.99 | 1.75 | 1.16 | 2.86 | .024 |

| Hallucinations | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 1.00 | .363 | 3.75 | 2.25 | 2.00 | 1.07 | 2.70 | .031 |

| Agitation | 1.33 | 1.64 | 0.67 | 0.81 | −1.34 | .235 | 2.50 | 1.85 | 1.25 | 0.71 | −2.76 | .028 |

| Anxiety | 2.67 | 1.63 | 0.63 | 0.74 | −3.87 | .012 | 1.75 | 2.18 | 0.63 | 0.74 | −2.05 | .080 |

| Apathy | 1.04 | 1.67 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 1.35 | .235 | 1.50 | 2.33 | 0.50 | 0.93 | 1.87 | .104 |

| Irritability | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.33 | 0.57 | 1.58 | .180 | 3.25 | 2.82 | 0.88 | 0.64 | 1.00 | .037 |

| Depression | 4.01 | 4.41 | 1.01 | 1.54 | 2.12 | .087 | 1.13 | 1.36 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 2.57 | .351 |

| Aggressiveness | 1.54 | 1.32 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 1.84 | .082 | 2.20 | 3.14 | 1.38 | 1.24 | 1.19 | .246 |

| Disinhibition | 1 | 1.57 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 2.48 | .024 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 0.38 | 0.71 | 2.58 | .017 |

| AMB | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 0 | 1.84 | .083 | 0.75 | 2.02 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 1.81 | .083 |

| Total | 12 | 5.75 | 4.66 | 2.63 | 8.11 | .000 | 22 | 25.59 | 9.75 | 5.07 | 7.46 | .000 |

| HADS | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 9.00 | 1.54 | 5.66 | 1.86 | 3.78 | .013 | 9.62 | 3.20 | 5.75 | 1.90 | 3.08 | .018 |

| Anxiety | 12.66 | 2.70 | 11.33 | 4.18 | 2.49 | .024 | 13.37 | 1.43 | 11.50 | 2.93 | 2.94 | .007 |

| Total | 21.67 | 3.49 | 17 | 5.41 | 5.74 | .000 | 23 | 3.02 | 17.25 | 2.59 | 6.96 | .000 |

| BI | 44.10 | 20.58 | 40 | 21.62 | 0.58 | .560 | 18.18 | 12.62 | 21.88 | 23.39 | −0.68 | .503 |

AMB: aberrant motor behaviour; SD: standard deviation; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; BI: Barthel Index; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

This study analysed the effects of music therapy on cognitive, psychological, and behavioural problems in patients with AD. According to our results, this type of intervention has a positive impact on symptoms in these patients. Music therapy lessened symptoms of most neuropsychiatric disorders, especially anxiety and depression; similar results have been reported in a recent study by Raglio et al.19 However, depression as measured on the NPI did not improve significantly. HADS and NPI measure different aspects of depression and were administered to different individuals (patients and carers, respectively). Furthermore, HADS focuses on symptoms of anhedonia and only evaluates symptom severity, whereas the NPI assesses frequency and intensity of physical symptoms.

Music therapy was found to improve delusions, hallucinations, irritability, and agitation in the group with moderate dementia, probably due to the higher intensity of symptoms in this group. This type of intervention has been found to reduce levels of agitation, leading to a decrease in the prescription of psychotropic drugs.20 According to Hall and Buckwalter,21 progressive cognitive impairment lowers the stress threshold. Thus, under stressful conditions, patients may display such behavioural problems as agitation or aggressiveness. Music therapy increases the level of tolerance to stressful environmental stimuli that may trigger such symptoms.22 In our study, music was found to have a major impact on anxiety and depression. Music is a pleasant stimulus, especially when it is adapted to one's personal preferences, and it can evoke positive emotions. It also affects the endocrine and autonomic nervous systems by decreasing stress-related activation of the adrenomedullary and parasympathetic nervous systems.23 Furthermore, holding interactive group sessions promote social relationships and improve the subjects’ moods.24 Groups were small in our study, which promoted participation, social interaction, and intimacy. Patients were familiar with the songs used during the intervention; as a result, they participated actively and their sense of competence increased.

Regarding cognitive function, orientation and memory improved regardless of dementia severity, which supports use of music therapy at different stages of the disease. Improvements in memory may have been favoured by using songs that were familiar to and appreciated by our patients. Recognition of the emotions associated with music seems to be preserved in patients with AD,25 which explains why these patients experience a rush of emotions and memories when they listen to familiar music.26 According to the literature, music enhances encoding of verbal information in healthy elderly individuals and in patients with AD.27,28 This may be explained by the fact that music alters the executive, associative, and auditory networks involved in brain plasticity and learning.29 Another possible explanation is that music increases arousal and reduces anxiety, states that promote attention and encoding in turn.30 Increased activation of brain plasticity mechanisms may also explain improved orientation in time and place. In line with this hypothesis, music has been suggested as a means of enhancing spatial reasoning skills.31 In addition, recalling music-associated memories is a technique used in reminiscence therapy.32 Our patients displayed language improvements, which is in line with results reported in the literature. Music has been observed to improve naming ability and speech fluency and content, as well as the drive to communicate, in patients with dementia.33,34 In fact, music training leads to recruitment of right hemisphere areas involved in speech processing, leading to improved language comprehension.35 We must stress that not all studies of music therapy for patients with dementia report significant improvements in cognitive function.24,36,37 Although some suggest that the effects of these interventions may remain in the long term,38 no studies have assessed whether gains persist after the intervention. Cognitive improvements may even be temporary and only present on the day following each music therapy session.39 In our study, cognitive function improved progressively throughout the intervention period; this finding may contradict the hypothesis that effects of music therapy are transient. Differences in results may stem from the type of intervention: active vs passive, individual vs group sessions, relaxation music vs pop music, etc. Further studies with large sample sizes and solid methodology should aim to explore the impact of these variables on treatment outcomes. Our results may have been influenced by the type of scale we used to assess cognitive function. The fact that we used short tests and administered them several times throughout the intervention period may have helped facilitate memory.

Despite changes in patients’ cognition and behaviour, music therapy had no impact on functional dependence, as the literature reports.40 Our results may be explained by the impact of certain factors. Our patients were severely dependent for activities of daily living. Combined motor and cognitive rehabilitation would therefore have been necessary to achieve any quantifiable improvements in function.

In summary, music therapy stimulates cognitive function, improves mood, and reduces behaviour problems triggered by stressful conditions. Music therapy, an inexpensive and pleasant intervention with no adverse effects, has emerged as a promising alternative for patients with dementia. Further controlled studies with homogeneous samples are necessary to support use of this technique. Results must be interpreted with caution due to the study's within-subjects design. Nevertheless, consistency and effect size underline the need for further controlled studies to rule out a placebo effect and analyse long-term residual benefits of music therapy sessions.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gómez Gallego M, Gómez García J. Musicoterapia en la enfermedad de Alzheimer: efectos cognitivos, psicológicos y conductuales. Neurología. 2017;32:300–308.