Metronidazole is an antimicrobial drug used widely across the world. The most significant adverse reactions reported include such gastrointestinal symptoms as nausea, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain. The central and peripheral nervous system can also be affected, although these reactions are less well known.

We describe the case of a 19-year-old man who underwent ileocecal resection to treat Crohn disease, and has since been under treatment with omeprazole at 20 mg/day, mesalazine at 2 g/12 hours, and metronidazole at 250 mg/8 hours. He visited the emergency department due to a 3-week history of progressive paraesthesia in the lower limbs, initially affecting the toes and ascending to the knees; unsteady gait; and glove-and-stocking paraesthesia. He had also developed impaired speech production in the days preceding consultation. Neurological examination identified scanning dysarthria; generalised hyperreflexia; wide-based gait, with the patient requiring assistance to walk; and reduced distal tactile sensitivity in all 4 limbs. There were no signs of cranial nerve involvement or motor deficits. Physical examination yielded normal results.

A complete blood count and biochemistry study identified no abnormalities, with the exception of AST, ALT, and GGT levels (55 U/L, 105 U/L, and 126 U/L, respectively). Alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin levels were within normal ranges. We also ordered ANA and ANCA antibody tests, HIV and syphilis serology studies, and urine toxicology testing; all results were normal. Anti-NMO and anti-MOG antibody tests were not requested. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasound identified no relevant alterations.

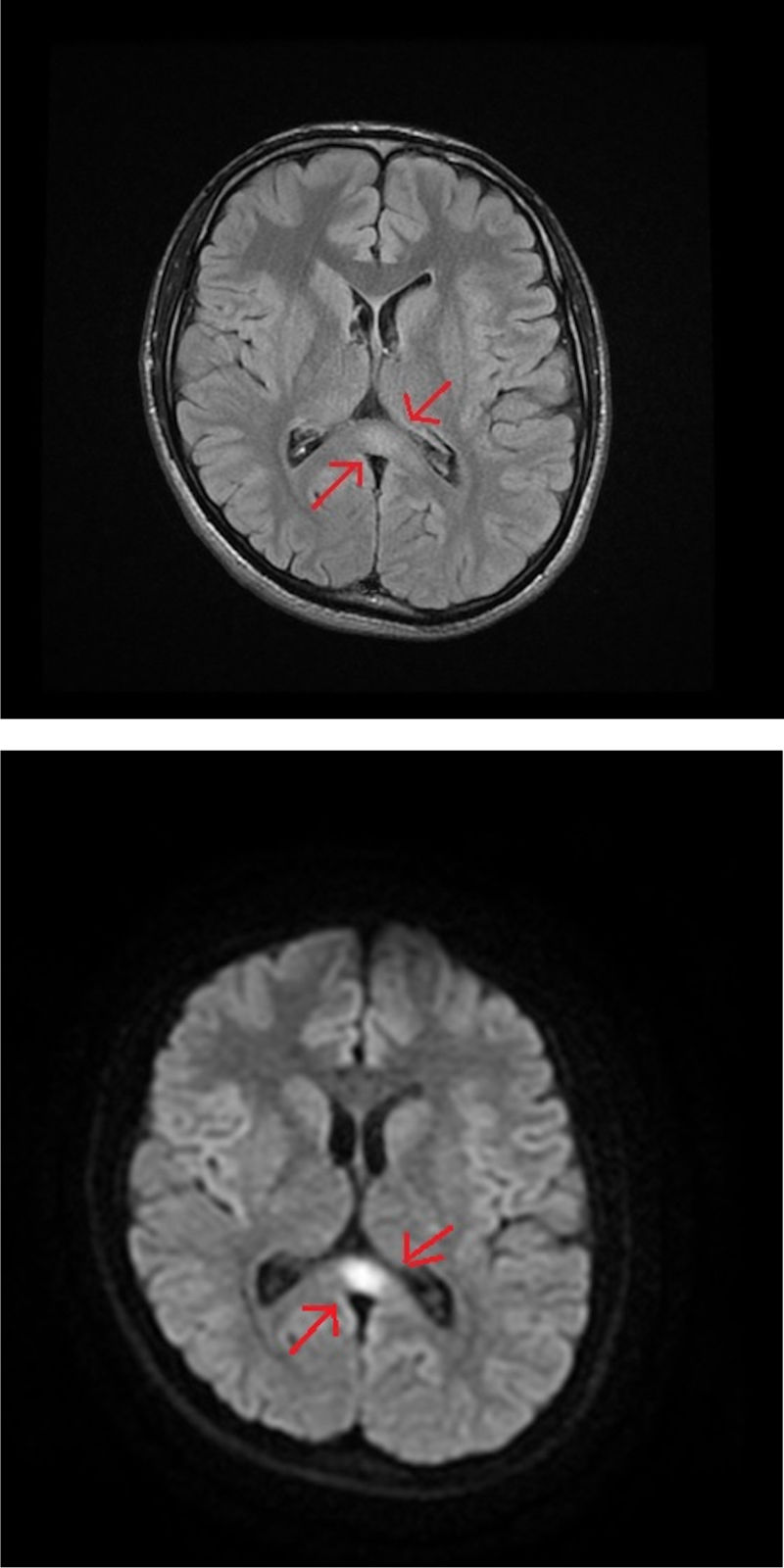

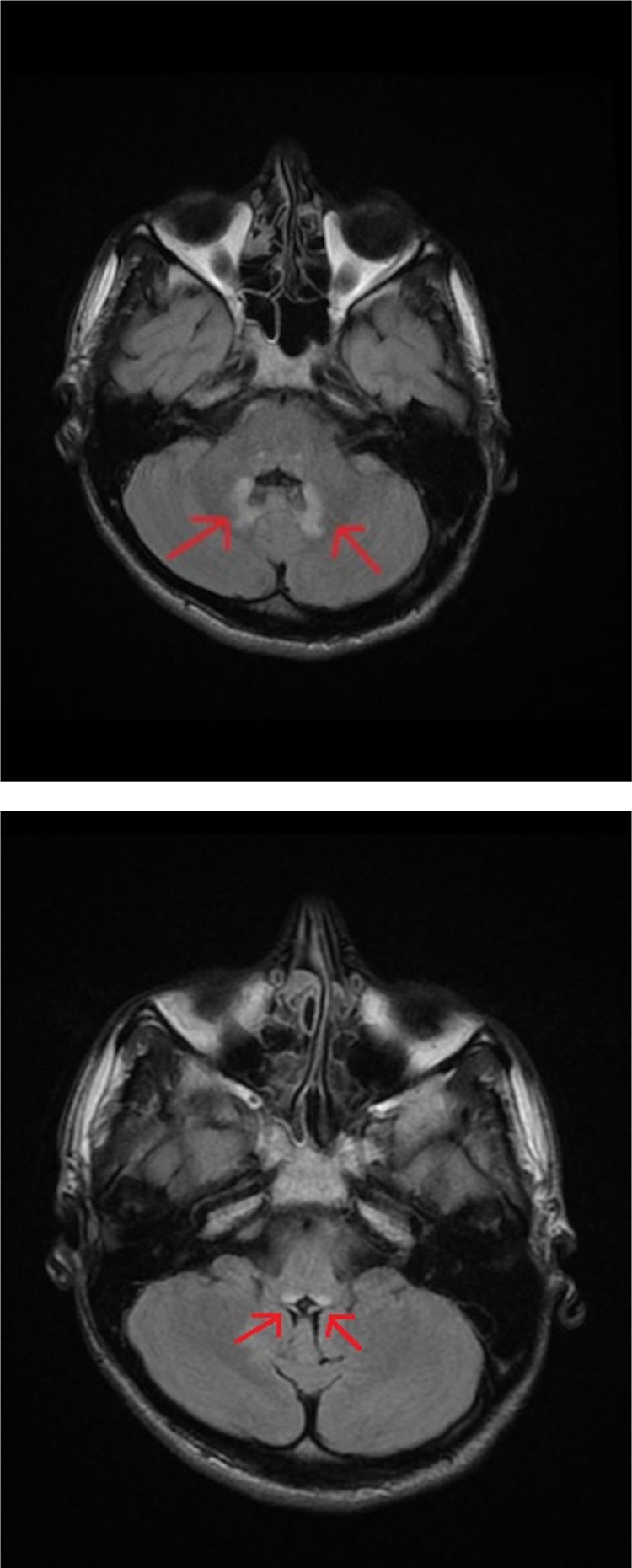

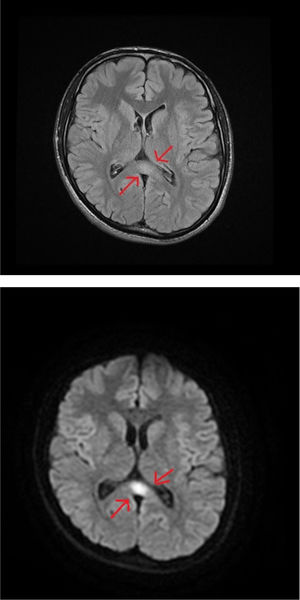

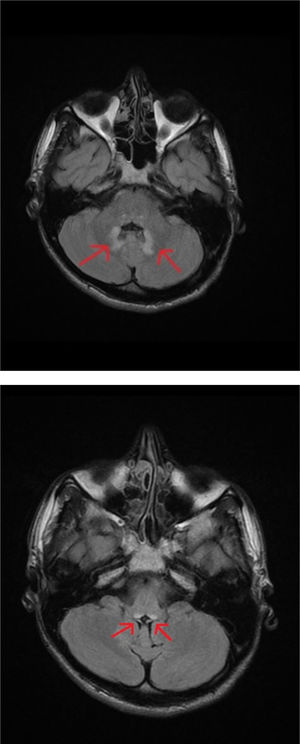

An MRI study of the brain and cervical/thoracic spinal cord detected a poorly-delimited lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum, measuring 1.5 cm. The lesion was discreetly hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, isointense on T1-weighted sequences, and markedly hyperintense on diffusion-weighted sequences, without contrast administration (Fig. 1A and B). T2-weighted sequences also displayed small lesions in the posterior part of the medulla oblongata and the dentate nuclei, showing symmetrical distribution (Fig. 2A and B). These findings are suggestive of toxic/metabolic aetiology. A further clinical history interview was performed, and the patient denied having consumed any type of toxic substance. We reviewed the medications he was receiving and noted the continued use of metronidazole at 250 mg/8 hours between May and October of that year. The patient had not attended the postoperative follow-up consultation, and therefore had been taking metronidazole for a 5-month period. The drug was suspended, and symptoms progressively improved in the first week, particularly the language alterations and unsteady gait; at discharge, he continued to present paraesthesia in the lower limbs, from the knees to the feet, and slight paraesthesia in the fingers. An electroneurography study was performed, revealing moderate, bilateral sensorimotor polyneuropathy, which was predominantly axonal and affected the sensory nerves. A brain MRI scan performed 4 months later showed complete resolution of the lesions; a follow-up electroneurography study showed persistence of the axonal alterations affecting the sensory nerves.

While the precise mechanism of metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity is not fully understood, the main hypothesis is that the drug causes vascular spasm, leading to mild, reversible ischaemia presenting as hyperintense lesions on diffusion sequences, as was the case with the lesion we observed in the splenium of the corpus callosum. These lesions are also observed in Marchiafava-Bignami disease; this entity must therefore be considered in differential diagnosis. However, the cause of the other MRI findings is unclear. Other pathophysiological mechanisms may include the modulation of GABA receptors, particularly in the cerebellar and vestibular system,1,2 and reduced thiamine levels due to the conversion of metronidazole into an analogous metabolite.3 Neurological complications are typically observed in patients receiving doses greater than 2 g/day for prolonged periods4 or with poor nutritional status or chronic diseases, which may increase susceptibility to toxicity.5

Radiology studies may detect lesions in various locations. The area most frequently involved is the dentate nucleus, followed by the splenium of the corpus callosum, the basal ganglia, the thalamus, and the cerebellar peduncles. Lesions are characterised by symmetrical distribution, hyperintensity on T2-weighted or FLAIR sequences, hypointensity on T1-weighted sequences, and isointensity or hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted sequences.6 Symptoms usually include various forms of progressive neurological impairment, such as cerebellar syndromes (gait disorders, dysarthria, and dysmetria); encephalopathy; seizures; and autonomic, optic, or peripheral neuropathy. Differential diagnosis should consider inflammatory diseases (neuromyelitis optica, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis), autoimmune diseases (systematic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome), infection (tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, HIV, syphilis), and metabolic causes (Wernicke encephalopathy, Marchiafava-Bignami disease).7 The reversible nature of clinical and radiological signs after suspension of the drug distinguishes this entity from other diseases; however, strong clinical suspicion is needed given the low incidence of this adverse reaction. Early diagnosis with brain MRI studies and rapid suspension of the drug are beneficial in most cases.

Please cite this article as: Augustín-Bandera V, Aguilar-García JA, Aparicio-Camberos J, Romero-Gómez C. Neurotoxicidad inducida por metronidazol. Nefrologia. 2020;35:655–657.