Primary central nervous system vasculitis (PCNSV) is a rare disease affecting medium- and small-calibre blood vessels of the central nervous system.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to analyse clinical findings and diagnostic aspects, with special attention to histopathological findings, as well as the treatments used and treatment response in patients diagnosed with PCNSV at our hospital.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a retrospective descriptive analysis of patients with a diagnosis of PCNSV at discharge from our centre and meeting the 1988 Calabrese criteria. To this end, we analysed the hospital discharge records of Hospital General Universitario de Castellón between January 2000 and May 2020.

ResultsWe analysed a series of 7 patients who were admitted with transient focal alterations and other less specific symptoms such as headache or dizziness; diagnosis was based on histological findings in 5 cases and on suggestive arteriographic findings in the remaining 2. Neuroimaging results were pathological in all cases, and CSF analysis detected alterations in 3 of the 5 patients who underwent lumbar puncture. All patients received initial treatment with megadoses of corticosteroids followed by immunosuppressive treatment. Progression was unfavourable in 6 cases, with fatal outcomes in 4.

ConclusionsDespite the diagnostic challenge of PCNSV, it is essential to attempt to reach a definitive diagnosis using such tools as histopathology and/or arteriography studies, in order to promptly establish appropriate treatment and thus reduce the morbidity and mortality of this condition.

La vasculitis primaria del sistema nervioso central (VPSNC) representa una enfermedad rara que afecta a los vasos sanguíneos de mediano y pequeño calibre del sistema nervioso central.

ObjetivoRealizar una descripción de los hallazgos clínicos y aspectos diagnósticos, con especial atención a los hallazgos histopatológicos, así como los tratamientos utilizados y la respuesta a los mismos en pacientes diagnosticados de VPSNC en nuestro centro.

Pacientes y métodosPresentamos un análisis descriptivo retrospectivo. Se ha analizado el registro de altas hospitalarias del Hospital General Universitario de Castellón entre enero de 2000 y mayo de 2020, escogiéndose aquellos con diagnóstico al alta de VPSNC que reunían los criterios de Calabrese en 1988, una vez revisada la historia clínica.

ResultadosSe analiza una serie de siete pacientes que ingresaron con cuadros de alteraciones focales transitorias y otros más inespecíficos como cefalea o mareo, alcanzándose el diagnóstico mediante histología en cinco de ellos y mediante angiografía sugestiva en los dos restantes. La neuroimagen fue patológica en todos los casos y el estudio de LCR resultó alterado en tres de los cinco casos practicados. Todos ellos recibieron tratamiento inicial con megadosis de corticoides seguido de tratamiento inmunosupresor. La evolución fue desfavorable en seis casos, resultando éxitus cuatro de ellos.

ConclusionesA pesar del reto diagnóstico que representa la VPSNC, es fundamental tratar de aproximarse al máximo al diagnóstico definitivo, valiéndonos de herramientas como la histopatología y/o angiografía para establecer un tratamiento adecuado de manera precoz y reducir así la morbi-mortalidad de esta entidad.

Primary central nervous system vasculitis (PCNSV) is a rare disease resulting from the inflammation and subsequent destruction of small- and medium-calibre vessels of the brain parenchyma, spinal cord, and meninges, with no involvement of other organs.1,2 This process results in ischaemic and haemorrhagic events in nearby tissues, causing a wide range of clinical manifestations.3,4

PCNSV is more frequent in men, and presents an incidence of 2.4 cases per million person-years and a mean age at diagnosis of 50 years.2,4–7

The wide spectrum of clinical manifestations and the lack of specific diagnostic tests hinder the diagnosis of this condition.1,2,4–6,8

Serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) laboratory test results and electroencephalography findings are not specific for PCNSV.1,6,8

Neuroimaging is useful to rule out other diagnoses, with MRI being the technique of choice due to its high sensitivity and specificity.1,4,6 Computed tomography (CT) angiography, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) are useful in assessing vascular involvement.1,9

Although DSA has traditionally been considered the neuroimaging technique of choice, revealing alternating narrowing and dilation of blood vessels in the absence of atheromatosis or other vascular anomalies,3,10 recent improvements in the resolution of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques have led some authors to suggest that MRA may be diagnostic in a high percentage of cases, with angiography providing no additional information.9

The gold standard technique for the diagnosis of PCNSV is the histopathological study of the brain and leptomeninges,2 which shows transmural vascular inflammation of cerebral or leptomeningeal blood vessels, with or without vessel wall necrosis.3,5–8,11,12 However, in clinical practice, there is still debate as to whether arteriography or biopsy should be used to achieve diagnostic certainty,8,11–17 with some authors considering typical arteriography findings to be sufficient to start early treatment.

Great controversy remains about the diagnostic criteria and technique to be used to establish a definitive diagnosis of PCNSV, due to a lack of real consensus; this further complicates the diagnostic process.8,13–15

Despite their rareness, all types of cerebral vasculitis are severe, disabling, and potentially fatal.5,8,15,17 Relapses occur in nearly one-third of patients,2 with mortality reaching 10% despite treatment.18,19

It is important to differentiate PCNSV from other entities presenting with similar characteristics, with a view to providing early, appropriate treatment, as other diseases may be resistant to or even exacerbated by immunosuppressive therapy.4,10

ObjectiveThe purpose of this study is to describe the clinical findings and diagnostic characteristics of PCNSV, with particular emphasis on the utility of histopathological studies and the treatment tools used, in patients diagnosed with PCNSV in our centre over the last 20 years. We also analysed treatment response and complications.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a retrospective, descriptive, observational study to analyse the discharge records of Hospital General Universitario de Castellón, in Spain, between January 2000 and May 2020.

We selected patients with a diagnosis of PCNSV at discharge and meeting the criteria established by Calabrese and Mallek in 1988: 1) clinical findings of a new-onset acquired neurological or psychiatric deficit, whose origin remained unexplained after the initial evaluation; 2) angiographic or histopathological features of PCNSV; and 3) no evidence of systemic disease associated with the findings.20

Lastly, we retrospectively studied the patients’ medical histories to gather data on clinical characteristics, diagnostic tests, treatment, and progression.

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive statistical analysis; continuous quantitative variables are expressed as mean or median and qualitative variables as frequency and percentage. We used the SPSS software for statistical analysis.

Ethics approvalWe did not collect personal data allowing patient identification. All the data collected were anonymised.

The study was classified as a non-post-authorisation observational study by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices, and was also approved by our hospital’s drug research ethics committee.

ResultsClinical presentationWe included 7 patients who were admitted to our centre due to focal neurological signs and other nonspecific findings, such as dizziness or headache; a definitive diagnosis of PCNSV was established based on histological findings in 5 patients (71.4%) and angiography findings in the remaining 2 (28.6%).

The male-to-female ratio was 6:1, with a mean age at diagnosis of 62.1 years (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical features, and comorbidities in the sample.

| Age (years) | Sex | Symptoms at onset | Comorbidities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 74 | Man | Stroke: loss of strength and poor coordination of the arm, dizziness | AHT, DL, DM type 2, CKD treated with HD |

| Patient 2 | 81 | Man | Recurrent focal symptoms: recurrent episodes of dizziness, memory loss, mood swings | Atrial fibrillation |

| Patient 3 | 72 | Man | Stroke: gait instability and speech alterations | AHT, DL, OSAS, prostate cancer |

| Patient 4 | 66 | Woman | Recurrent focal symptoms: recurrent episodes of visual alterations, poor coordination, speech alterations | AHT, DL |

| Patient 5 | 43 | Man | Headache and recurrent focal neurological signs: recurrent episodes of transient visual alterations and diplopia | – |

| Patient 6 | 47 | Man | Headache | DL |

| Patient 7 | 52 | Man | Recurrent focal neurological signs: recurrent episodes of speech and behavioural alterations | AHT, DL, atrial fibrillation, smoking |

AHT: arterial hypertension; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DL: dyslipidaemia; DM: diabetes mellitus; HD: haemodyalisis; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome.

The most frequent clinical manifestations at onset were focal neurological signs (eg, visual, behavioural, or cognitive alterations) in 4 patients (57.1%). The behavioural and cognitive symptoms observed were memory alterations, emotional lability, and verbal aggressiveness. Two patients (28.6%) presented headache as the initial manifestation, and another 2 presented symptoms suggestive of stroke, including motor symptoms and speech alterations (Table 1). Symptom onset was acute in 2 patients, who presented symptoms compatible with stroke, subacute (several weeks’ progression) in 4, and chronic progressive (several months’ progression) in one.

The following comorbidities were recorded: dyslipidaemia (5 patients; 71.4%), arterial hypertension (4; 57.1%), atrial fibrillation (2; 28.6%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (1; 14.3%), chronic kidney disease treated with haemodialysis (1), smoking (1), obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (1), and neoplasia (1) (Table 1).

Complementary testsBlood analysis results were normal in all cases, including levels of acute phase reactants, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

Serology and autoimmunity tests performed during hospitalisation to rule out other processes also yielded negative results in all cases. As part of the expanded study and to rule out tumours or vasculitis at other locations, we conducted chest-abdomen-pelvis CT scans in 5 patients and positron emission tomography in one; results were negative in all cases.

Five patients underwent lumbar puncture for CSF analysis, with 3 (60%) presenting CSF alterations (elevated protein levels in all cases, predominantly mononuclear pleocytosis in 2, and predominantly polynuclear pleocytosis in 1). IgG oligoclonal bands were positive in one patient.

Four patients (57.1%) underwent electroencephalography studies, which in all cases revealed nonspecific findings, such as slowing of brain activity, focal irritative activity, or diffuse dysfunction.

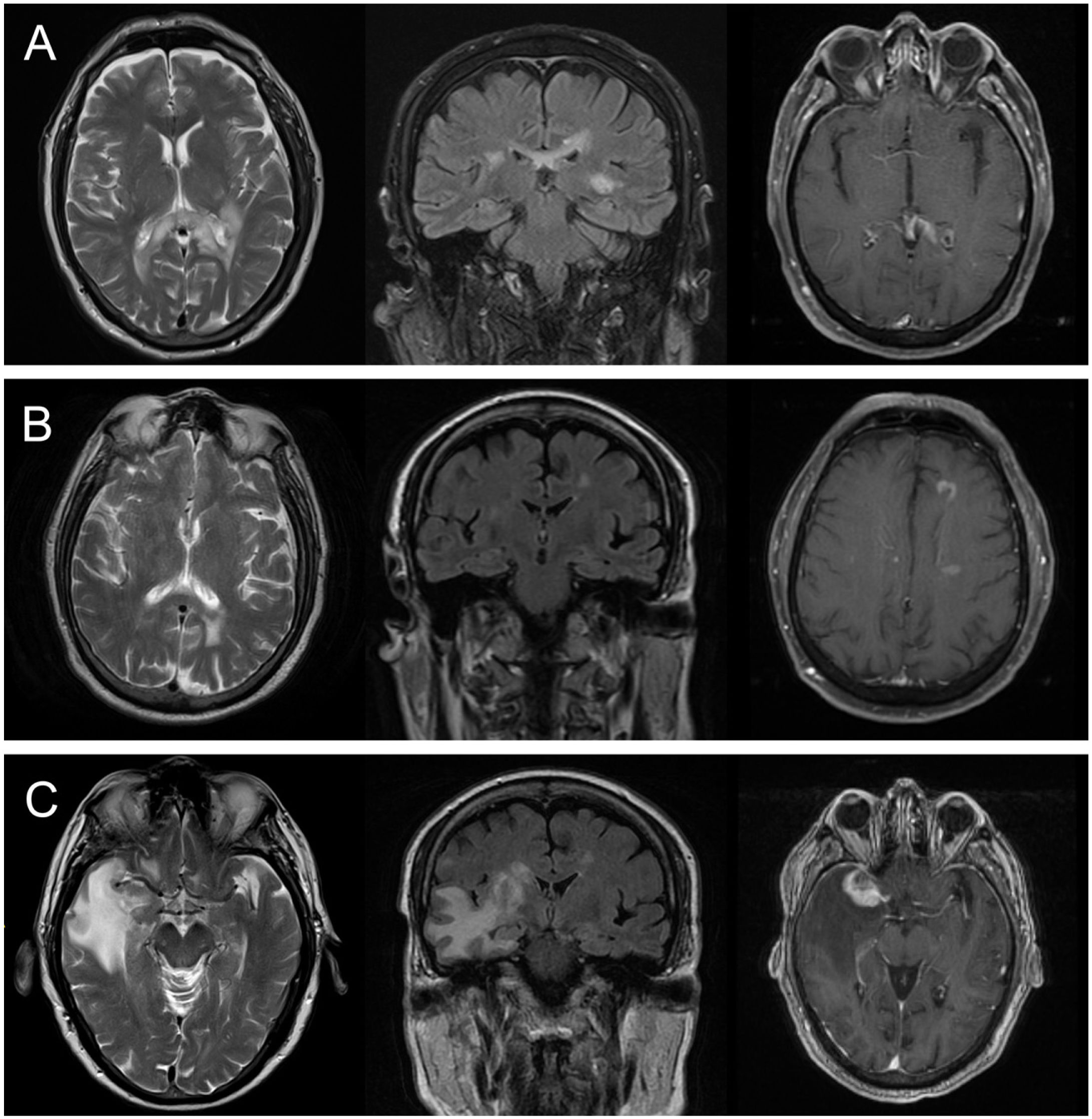

MRI studies were conducted for all 7 patients, revealing alterations in all cases (Table 2). Four patients (57.1%) presented vascular lesions and the remaining 3 (42.9%) presented inflammatory lesions. Fig. 1 presents the main neuroimaging findings from one of the patients in our series.21

Results from brain neuroimaging and biopsy studies.

| Brain MRI | Brain MRA | Cerebral angiography | Brain biopsy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesions | Location | Histopathological findings | Time to study | |||

| Patient 1 | Multiple haemorrhagic lesions | Supra- and infratentorial | SAT and circle of Willis with preserved morphology and calibre | – | Perivascular infiltrates with polymorphonuclear cells and CD68+ histiocyte accumulation | 41 days |

| Patient 2 | Multiple hyperintense lesions on FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences, with no alterations on DWI, and showing contrast uptake | Supra- and infratentorial | SAT and circle of Willis with preserved morphology and calibre | – | Perivascular inflammatory lymphocytic infiltration Increase in macrophages Chronic inflammatory changes with perivascular tissue destruction | 13 days |

| Patient 3 | Multiple ischaemic lesions with signs of haemorrhagic transformation | Supratentorial | Right M2 occlusion Irregularities in both MCA | Right M2 occlusion and significant left M2 stenosis Significant stenosis in left MCA territory | – | |

| Patient 4 | Multiple hyperintense lesions on FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences, with no alterations on DWI, and showing contrast uptake | Supratentorial | Intracranial arterial anomalies, with no evidence of occlusion | – | Vascular and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates with T cells, few B cells, and some histiocytes, and vascular damage | 56 days |

| Patient 5 | Multiple hyperintense lesions on FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences, with no alterations on DWI, and showing contrast uptake | Supra- and infratentorial | – | – | Meningoencephalitis with a major component of lymphocytic vasculitis, with occasional thrombosis and perivascular granulomatous lesions | 19 days |

| Patient 6 | Leptomeningeal uptakeMultiple ischaemic lesions | Supra- and infratentorial | Intracranial arterial anomalies in the circle of Willis | – | Post mortem examination: lymphocytic infiltrates, mainly T cells, showing an irregular, perivascular distribution | |

| Patient 7 | Multiple ischaemic lesions | Supra- and infratentorial | Intracranial arterial anomalies in the circle of Willis: 50% stenosis of right P1 and distal branches, 50% stenosis of left M1, stenosis of distal segments of right MCA | Stenosing vascular lesions in medium-calibre arteries in both ACA, MCA, and PCA, resulting in string-of-pearls configuration of the distal arteries | – | |

ACA: anterior cerebral artery; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MCA: middle cerebral artery; MRA: magnetic resonance angiography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PCA: posterior cerebral artery; SAT: supra-aortic trunks.

Brain MRI scan from patient 1. A) T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences showing a hyperintense lesion in the corpus callosum. B) Decrease in the size of the lesion at 6 months of follow-up. C) Development of a new lesion in the right temporal lobe, showing contrast uptake and increased intensity on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, at 18 months of follow-up.21

Regarding lesion location in radiology images, all patients presented supratentorial lesions, and 5 (71.4%) also presented infratentorial involvement; none of the patients presented spinal cord involvement. Lesions were bilateral in all 7 patients.

Six patients underwent MRA, which revealed alterations in the arteries of the circle of Willis in 4 cases (66.6%) (Table 2).

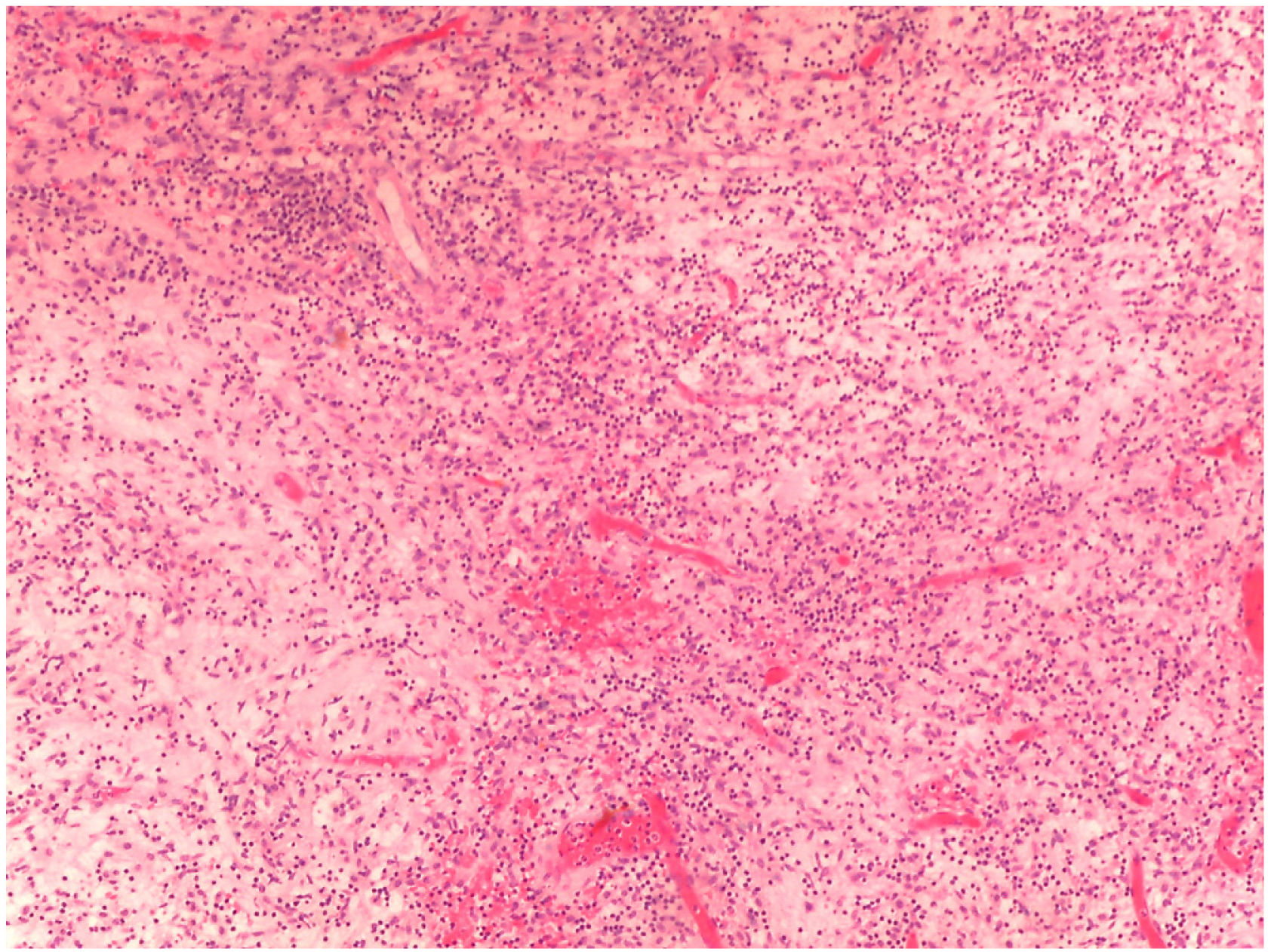

As explained previously, definitive diagnosis was established according to brain biopsy results in 5 patients (71.4%) and to angiography findings in the remaining 2 (28.6%) (Table 2). Figs. 2 and 3 show the histopathological findings from one of the patients in our series.21

Histopathological findings from a brain biopsy of patient 1. Chronic inflammation of intracerebral and leptomeningeal vessels, in and around the vascular walls.21

Histopathological findings from a brain biopsy of patient 1. Chronic inflammation of intracerebral and leptomeningeal vessels, around the vascular walls.21

In all patients, histopathological findings pointed to PCNSV as the principal diagnosis.

The mean time from admission to the neurology department to performance of a brain biopsy was 32.25 days.

In one patient, a post mortem examination was performed due to the lack of definitive diagnosis based on the results of a previous brain biopsy.

TreatmentAll 7 patients were initially treated with megadose corticosteroid therapy, followed by immunosuppressants (Table 3). Five patients (71.4%) received cyclophosphamide, 2 received rituximab (as the first-line treatment in one and as a second-line treatment following cyclophosphamide in the other), and one received methotrexate.

Treatment, complications, and follow-up time.

| Treatment | Complications | Follow-up time | mRS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of follow-up | ||||

| Patient 1 | Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (1 cycle) | Increased blood glucose level requiring an insulin pumpBilateral CMV pneumonia and thrombocytopenia secondary to infectionClostridium difficile–associated diarrhoeaUTI due to ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniaeAcute right lower limb ischaemia | 6 months | 0 | 6 (death) |

| Patient 2 | Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (3 cycles)Rituximab (2nd line) | Neurological deterioration despite treatmentUrinary sepsisClostridium difficile–associated diarrhoea | 9 months | 1 | 6 (death) |

| Patient 3 | Corticosteroids and rituximab (3 cycles) | Acute RSV bronchiolitisUTI due to Escherichia coli | 11 months | 0 | 4 |

| Patient 4 | Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (4 cycles) | Listeriosis in the context of immunosuppression | 94 months | 0 | 1 |

| Patient 5 | Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (4 cycles) | Neurological deterioration despite treatmentSecond brain biopsy: cerebral lymphoma | 25 months | 0 | 6 (death) |

| Patient 6 | Corticosteroids and methotrexate | Slow progression with subacute massive stroke | 2 months | 0 | 6 (death) |

| Patient 7 | Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (4 cycles) | Recurrent sepsis caused by a UTI due to ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae | 14 months | 0 | 5 |

CMV: cytomegalovirus; ESBL: extended-spectrum β-lactamase; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus; UTI: urinary tract infection.

Patients were followed up for a mean of 23 months. Four patients (57.1%) presented complications secondary to immunosuppressive therapy, associated with opportunistic infections in all cases (Table 3). Two patients presented urinary tract infection with extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, one patient presented Listeria monocytogenes infection, and another presented bilateral cytomegalovirus pneumonia.

Regarding quality of life, all patients presented a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0 before symptom onset.

Progression was unfavourable in 6 patients (85.7%), with clinical and/or radiological worsening despite treatment, which translated into higher mRS scores. Four patients (57.1%) died (mRS = 6), one within a short period of time (Table 3).

One of the patients was finally diagnosed with another condition: a second biopsy performed due to clinical worsening detected primary cerebral lymphoma.

DiscussionPCNSV continues to represent a major diagnostic challenge for clinical neurologists due to the great variability of clinical manifestations and the low specificity of standard complementary tests.1,2,9

No pathognomonic signs or symptoms have been described; rather, the condition presents with a wide range of clinical manifestations depending on the vessels involved.1,2

In our series, the clinical presentation of PCNSV was similar to that described in the literature; the only differences were the older mean age at diagnosis and the higher rate of patients presenting with focal neurological signs.1,2,5,7,10,17,22

Complementary tests should be performed to rule out other entities included in the differential diagnosis of PCNSV, including inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, infections, toxicity, and tumours.1 Brain MRI is the neuroimaging technique of choice when PCNSV is suspected; such alterations as intramural contrast uptake are highly suggestive of the condition.1 However, the most frequently used techniques for the assessment of brain blood vessels are MRA and DSA.1,9

In our series, no remarkable differences were observed in the results from blood and CSF analyses, neurophysiological tests, and neuroimaging studies with CT, MRI, and DSA.1,2,10,17,22,23

There is great controversy regarding the most appropriate diagnostic test for the final diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis.1 In fact, some authors support the use of diagnostic criteria based on angiography, while others consider histopathological studies to be more appropriate for definitive diagnosis; however, the 2 techniques cannot be considered equivalent due to the lack of agreement between their results.15 In fact, very few of the cases reported in the literature were evaluated with both techniques.15

DSA presents sensitivity of 40%–90% and specificity of 25%–35%, whereas the sensitivity of MRA is slightly lower.2 Due to the invasiveness of brain biopsy and the usefulness of brain DSA for the diagnosis of PCNSV in patients with compatible symptoms, many studies have opted for DSA to confirm the diagnosis and start immunosuppressive therapy.1,9,10

We would like to address some of the issues associated with the use of angiography as the main pillar of diagnosis. Firstly, today’s angiography equipment may yield normal results if the affected arteries are not sufficiently large.1,2 Some studies report normal angiography results in a considerable percentage of cases of histopathologically confirmed PCNSV.15 Thus, negative angiography results do not rule out PCNSV.4,5,7 Furthermore, the stenoses and irregularities in medium- and small-calibre cerebral arteries that are frequently detected with this technique may also be observed in other diseases affecting the anatomy of the cerebral arterial system,2,7,9 such as atherosclerosis, subarachnoid haemorrhage, migraine, trauma, infection, arterial hypertension, or drug abuse. Several published series have shown that some cases in which cerebral vasculitis is suspected due to compatible symptoms and angiographic alterations did not present histological findings typical of vasculitis in the biopsy.15

The main differential diagnosis is reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, which presents a similar pattern of artery involvement to that observed in vasculitis.1,2,14 This is probably explained by the fact that angiography reveals changes in vessel walls but does not provide data on the pathological process or the underlying mechanism. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome typically affects middle-aged women and presents with recurrent episodes of thunderclap headache, with or without associated neurological symptoms. Due to an alteration in the control of cerebral vascular tone, patients may present ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage, or brain oedema. Brain angiography reveals such vascular alterations as multifocal segmental cerebral artery vasoconstriction, which is more typically symmetrical and proximal, and resolves within 12 weeks of onset.

However, other authors assert that the risk of stroke associated with DSA, though low, is not negligible.9 According to this view, when MRA reveals more than 2 stenoses in at least 2 separate segments, DSA is not expected to add a significant diagnostic contribution in a patient with suspected cerebral vasculitis. Thus, these authors argue that DSA is only necessary when MRA yields normal results or when fewer than 3 stenoses are observed.1,9

The sensitivity of brain biopsy is estimated at 50%–70%. Other difficulties in establishing a definitive diagnosis are those resulting from the limitations of the anatomical pathology study. Physicians are naturally reluctant to perform invasive procedures; however, several studies have shown the relative safety of biopsy, with very low rates of adverse reactions to the procedure.1 However, we should bear in mind that biopsy may yield false negative results due to the segmental nature of this entity.1,2 To improve the performance of the test, cortical and leptomeningeal tissue samples should be taken,1,2 as well as samples from areas displaying abnormal neuroimaging results.

One of the factors contributing to the standstill in the diagnosis of PCNSV and the lack of clear diagnostic criteria is the fact that most of the published cases lack histopathological data.17 Despite this, there is broad consensus on establishing a diagnosis of probable PCNSV in cases lacking histopathological confirmation and definite PCNSV in the presence of histopathological evidence of the disease.

Given the nature of PCNSV and the high associated morbidity and mortality rates, we support the use of biopsy and consider anatomical pathology studies to be the only tool capable of providing a definitive diagnosis.1,2 Furthermore, as other authors have postulated, histopathological studies should be performed whenever possible given the higher rate of complications associated with immunosuppressive therapy than with biopsy.1 Differential diagnosis should be performed as soon as possible to establish a reliable diagnosis and start early treatment.4,10

We should highlight the high proportion of histopathology studies performed in our series (5 out of 7 cases), which was useful in establishing a definite diagnosis of PCNSV in 4 patients.

PCNSV is widely believed to be a heterogeneous syndrome encompassing a broad spectrum of diseases characterised by vascular inflammation, with reported cases of vasculitis associated with primary cerebral lymphoma.1,2,5 This may explain the false negative results of the first biopsy in one of our patients.

All our patients received immunosuppressive therapy, as megadose corticosteroid therapy was insufficient to control the disease in all cases. The most frequently used immunosuppressant was cyclophosphamide, followed by rituximab. These findings are similar to those of other published series, as few changes have been introduced in treatment recommendations in the last decades.1,2,7,10,17,23

Unlike in other published series,7,10,16,19,22,24 such as the one by De Boysson,17 who reported a high rate of remission, a mortality rate of only 8%, and an mRS score ≤ 2 at the end of follow up in half of the sample, in our series prognosis was poor despite treatment, with a large proportion of patients presenting clinical and/or radiological worsening, leading to fatal outcomes. There are several possible explanations for these results. On the one hand, they may be due to factors traditionally associated with poor prognosis, such as older age at diagnosis, evidence of stroke on MRI, and involvement of large-calibre vessels.7,14 These unfavourable results may also be due to multimorbidity, as our patients were older.

Despite the small size of our sample, which limits our ability to draw conclusions, we would like to highlight the importance of biopsy-based histopathological diagnosis in selected cases, in order to shorten diagnostic delays and provide early treatment with a view to improving prognosis and reducing the degree of functional disability.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.