The lack of accepted homogeneous criteria for the definition of some demyelinating diseases makes diagnostic characterization difficult and limits data interpretation and therapeutic recommendations. Recurrent encephalomyelitis (ADE-R) along with borderline cases of neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is especially controversial.

ObjectiveTo describe the clinical and radiological evolution of an adult-onset ADE-R versus NMO case throughout 9 years of follow-up.

Patient and methodsOur patient presented with severe symptoms of rhombencephalomyelitis and the cranial and spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed large lesions, with gadolinium enhancement in brainstem and spinal cord, correlating with the clinical picture. Infectious aetiology was excluded, IgG index was normal and NMO antibodies were negative. After treatment with intravenous corticosteroids and plasmapheresis, there was excellent recovery in the acute phase. During follow-up, seven relapses have occurred, mainly in the spinal cord, with good recovery and the same symptomatology, albeit with different severity. Immunosuppressive treatment was introduced since the beginning.

ConclusionsOur case shares common features of both ADE-R and NMO, illustrating that diagnostic characterization is not easy in spite of current criteria.

La falta de criterios homogéneos aceptados para la definición de algunas de las patologías desmielinizantes dificulta la caracterización diagnóstica limitando la reproducibilidad de los resultados y las recomendaciones terapéuticas. Especialmente controvertidas son las formas de encefalomielitis recurrentes (EAD-RR) y otras formas infrecuentes de neuromielitis óptica (NMO).

ObjetivoDescribimos la evolución clínico-radiológica de un caso de EAD-RR del adulto versus NMO, seguida durante 9 años.

Paciente y métodosLa paciente debutó con síntomas severos de rombencefalomielitis y la resonancia magnética (RM) craneal y medular mostraron lesiones extensas, con captación de gadolinio en el tronco encefálico y de la médula, acorde con los síntomas clínicos de la paciente. Se excluyó etiología infecciosa, el índice IgG fue normal y fueron negativos los anticuerpos para NMO. Tras tratamiento con corticoides por vía intravenosa y plasmaféresis la recuperación del episodio fue excelente. Durante el seguimiento ha presentado 7 recurrencias, preferentemente medulares, con buena recuperación, que reproducen con severidad variable los mismos síntomas. Desde el inicio ha recibido tratamiento inmunosupresor.

ConclusionesNuestro caso comparte características clínicas con EAD-RR y NMO e ilustra que, pese a los criterios vigentes, la caracterización diagnóstica de estas entidades no es fácil.

Idiopathic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease. It primarily affects children and is usually preceded by viral infections or vaccines, with a latency between 2 and 30 days and a higher incidence in winter.1–4 Its causes do not include infections5–7 or neoplasms.8 The aetiopathogenic hypothesis explains it as an inadequate immune response against antigens of the central nervous system (CNS), released after damage by neurotropic agents or by molecular analogy.3,4 The neurological manifestations of ADEM are often polysymptomatic,1,9 cerebral and, less commonly, medullar. The most common signs of ADEM in children4 are alterations in level of consciousness or behaviour,10 fever, meningism and epileptic crises.1–3,11,12 In adults it is rare and the most prevalent symptoms are motor, sensory, ataxia and alterations in speech or level of consciousness.2,4,9,13 ADEM is usually monophasic,3 although 5.5%–25% of cases present recurrences.10 These may occur in the same initial topography (ADEM-R) and, for some authors, in other locations (multiphasic ADEM).1,2,4,10 Both of them, especially the multiphasic form, are the subject of much controversy since the differential diagnosis with MS3,10,11 carries prognostic and therapeutic implications.4

Radiologically, ADEM usually exhibits more extensive lesions in the cerebral white matter than those caused by MS.1,9 Gadolinium uptake is variable,3 but a simultaneous uptake points more towards ADEM.9 Gray matter lesions, mainly in the basal ganglia, may be bilateral and occur in up to 60% of cases,9 while they are infrequent in the first demyelinating event in MS. The presence of “Dawson's fingers” in T1-weighted sequences should direct towards an alternative diagnosis to ADEM.3,11 Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may be normal or present lymphocytic pleocytosis and hyperproteinorrachia.1 Oligoclonal bands (OCB) are often absent or disappear during follow-up, contrary to what has been described in MS.1 Histopathologically, ADEM can be distinguished from MS by the existence in the former of perivenular demyelination “bands” with prominent inflammatory infiltrate at the expense of macrophages. Lesion margins are poorly defined.14,15 Typically, patients are treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (ivMTP) at high doses3 during acute episodes. Plasmapheresis16,17 and intravenous immunoglobulins18 are therapeutic alternatives9 in severe cases that are unresponsive to corticosteroids. The prognosis of monophasic ADEM is variable; 37%–81% of patients present a complete resolution of symptoms.2,11 Mortality (5%–25%) is associated with respiratory failure due to bulbar involvement.4 There is little experience regarding the treatment of ADEM-R; some authors have proposed immunosuppressors,12 cyclophosphamide2,11,12 and mitoxantrone.4,12

For its part, neuromyelitis optica (NMO) or Devic's disease is characterised by recurrent episodes of optic neuritis and myelitis, which are usually disabling.15,19 Infrequently, NMO may present bulbar symptoms, such as hyperemesis and respiratory dysfunction, or even appear as a transverse myelitis.20 The MRI scan of NMO usually reveals extensive medullar lesions of more than vertebral 3 segments18,20 and, in most cases, the cerebral white matter is normal. Determination of the anti-aquaporin 4 antibody in 200421 enabled differentiation between this entity and MS and the detection of intermediate or “NMO spectrum” forms whose evolution is still to be determined.19,20 However, false negatives can reach 30%–45% of the total, especially in cases treated with immunosuppressive drugs.19 Therapeutic options during the acute phase include intravenous methylprednisolone (ivMTP)20 and occasionally plasmapheresis17 or intravenous immunoglobulins (ivIg).18 As in ADEM-R, there are currently no randomised trials evaluating the treatment of recurrent NMO to prevent recurrences.1,20

ObjectiveThe aim of this study is to describe the clinical and radiological characteristics of a 21-year-old female patient with recurrent rhombencephalomyelitis who was monitored for 9 years, as well as to discuss diagnostic options and therapeutic considerations.

Patient and methodsThe patient was a 21-year-old female with no prior history of systemic or autoimmune disease, diagnosed with gastritis at the emergency department in February 2003, due to a 2-day history of vomiting, fever and mesogastric pain. Eight days later she reported progressive difficulty swallowing odynophagia, and uncontrollable vomiting. A thoracoabdominal CT scan and an urgent endoscopy were both normal.

Subsequently, the patient was again examined due to dyspnoea, pharyngeal foreign body sensation, phonatory difficulty and choking, with lancinating pain and painful dysesthesia throughout a broad band in the thoracolumbar region. She had no history of vaccination or infection prior to these symptoms. The general physical examination was normal. Upon exploration by a neurologist she presented limitation of left eye abduction and multidirectional nystagmus in all gaze positions, abolition of the gag reflex, significant dysarthria and breathing difficulty. Barre's manoeuvre was positive in the right upper limb and osteotendinous reflexes were hypoactive. She presented a band of hypoalgesia at the level of D4–L1, altered proprioceptive sensitivity in all four limbs, and dysmetria in the left upper limb. Visual acuity and fundus were normal.

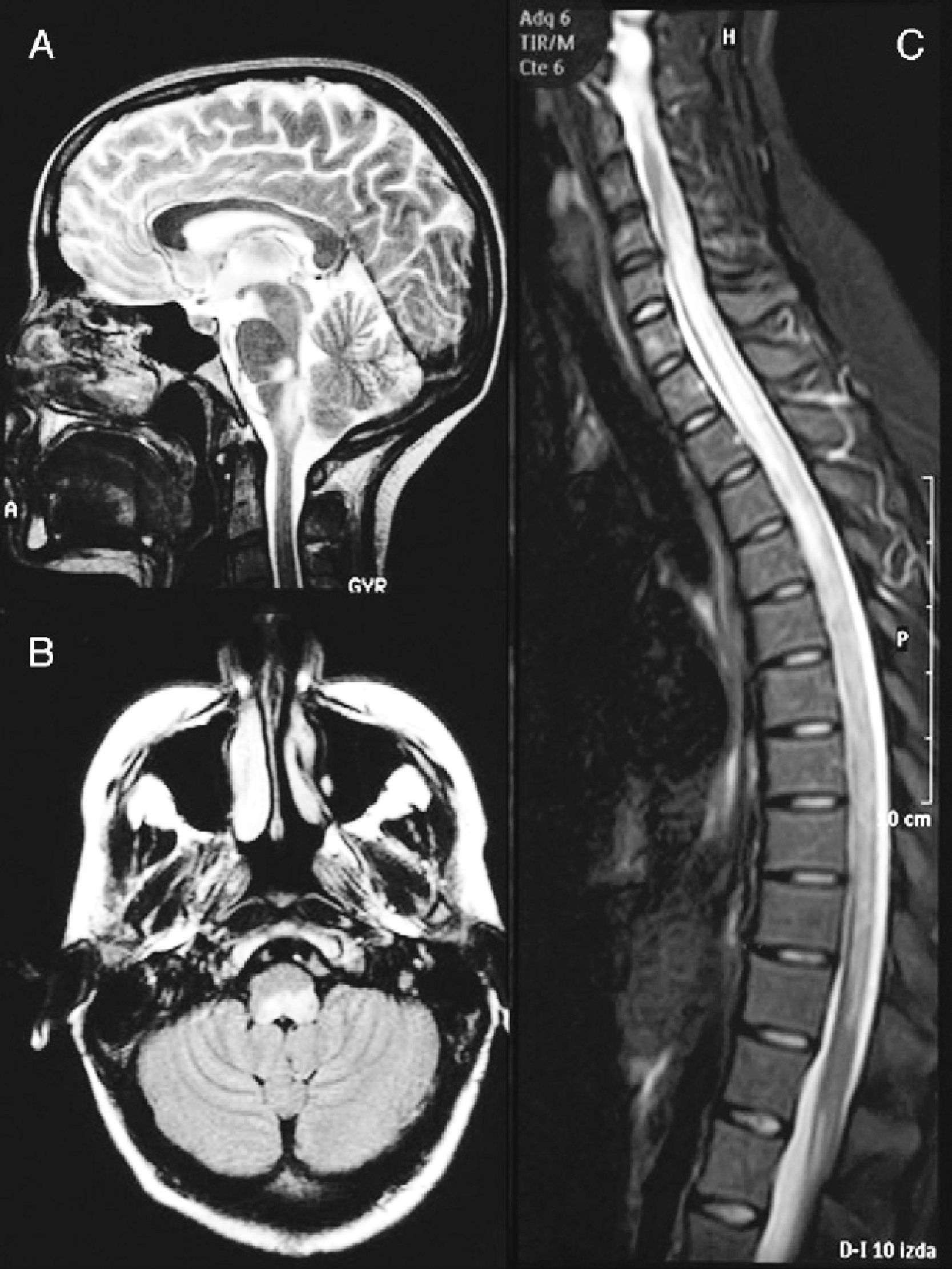

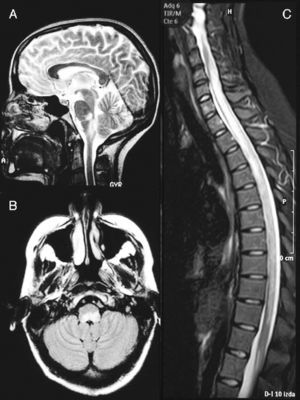

A cranial MRI scan (Fig. 1A) showed hyperintense lesions in T2 sequences in two-thirds of the dorsal bulb, with compression of the fourth ventricle and left cerebellar peduncle. A spinal MRI scan (Fig. 1B) revealed a hyperintense band from C4 to L1 in T2-weighted sequences. The CSF presented pleocytosis (50/μl) with monocyte predominance, sterility, proteins at 62mg/dl and glucose at 84mg/dl. The IgG index was normal and OCBs were not obtained. The microbiological study ruled out infectious aetiologies (Borrelia, Brucella, Mycoplasma, parvovirus, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, toxoplasmosis, enteroviruses, mycobacteria, acquired immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C and HBV virus, Listeria, Gram, auramine). The serological study ruled out autoimmune or tumoural causes.

Brain MRI image at the time of diagnosis (February 2003). Sagittal section in T2 (A) and axial FLAIR (B) sequences, revealing an altered signal at the level of the dorsal bulb, exerting a mass effect on the fourth ventricle. (C) Medullar MRI image in STIR sequence without contrast, showing an extensive signal alteration from C4 to L1, with slight mass effect.

The initial diagnosis was autoimmune rhombencephalomyelitis. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with respiratory distress secondary to aspiration pneumonia. She was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and ivMTP for 5 days. Due to her poor response to corticosteroids, she was treated with 5 cycles of plasmapheresis followed by iv Ig at doses of 0.4mg/kg/day for 5 days. At discharge, 1 month after admission, she presented paresis of the left sixth cranial nerve, multidirectional nystagmus and walked unaided, but was unsteady.

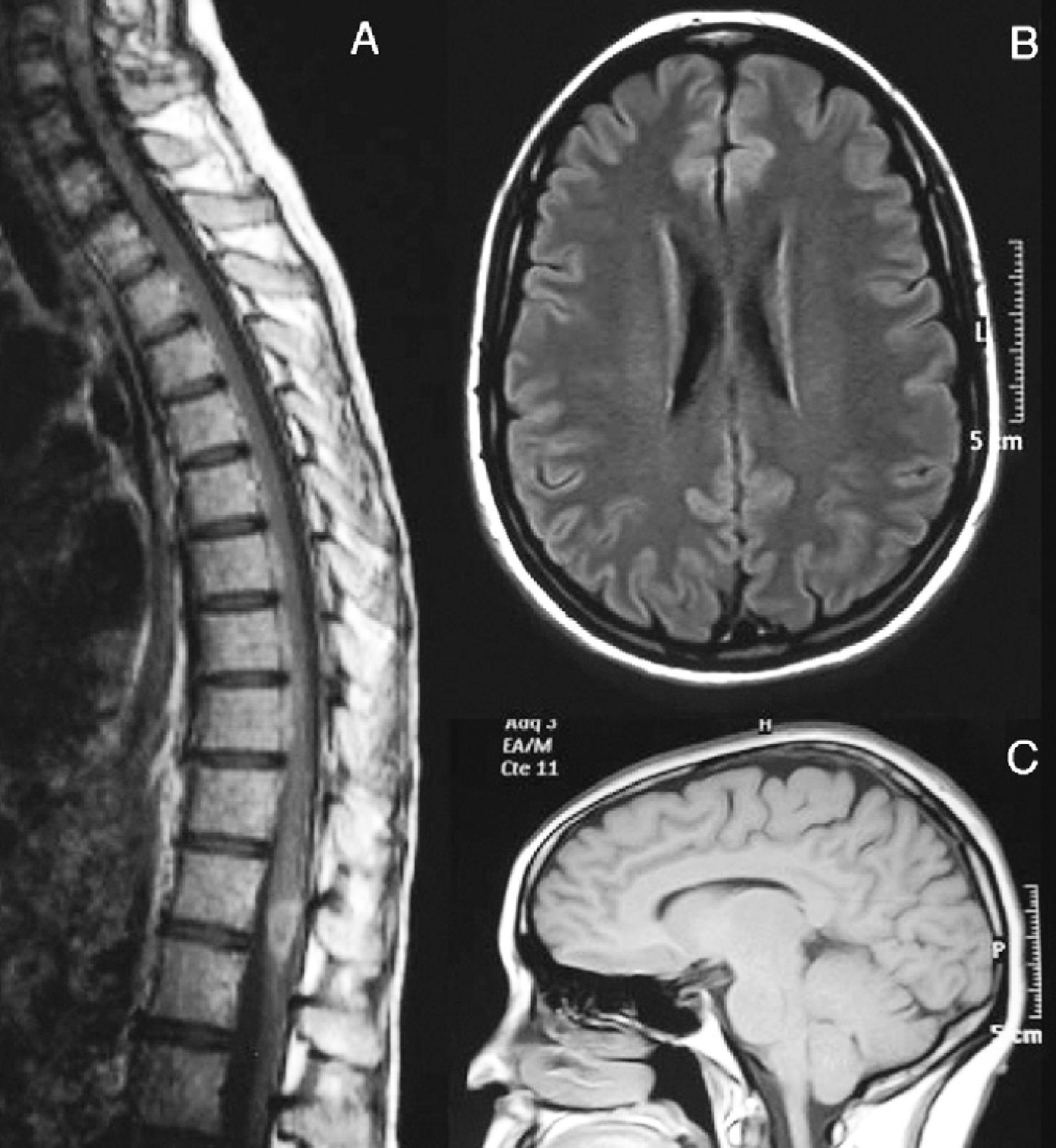

Subsequently, the patient presented 7 spontaneous relapses (Table 1). Of these 7 relapses, 4 consisted in mild-moderate myelitis with motor and/or sensory involvement, all at the dorsal level, from which she recovered after a few days. The first relapse coincided with removal of glucocorticoids. Treatment with azathioprine was started. The remaining relapses consisted of bilateral, paroxysmal pain in a half-band, associated with bilateral metameric hypoalgesia at the level of D5–D10. During the clinical course, visual evoked potentials were normal and serologies for HTLV-1 and anti-aquaporin 4, conducted during one of the relapses (May 2007), were negative. Regarding the MRI scan, the medullar lesion showed gadolinium uptake during various clinical relapses, whilst no other cranial or spinal injuries or signs of axonal damage were observed (Fig. 2).

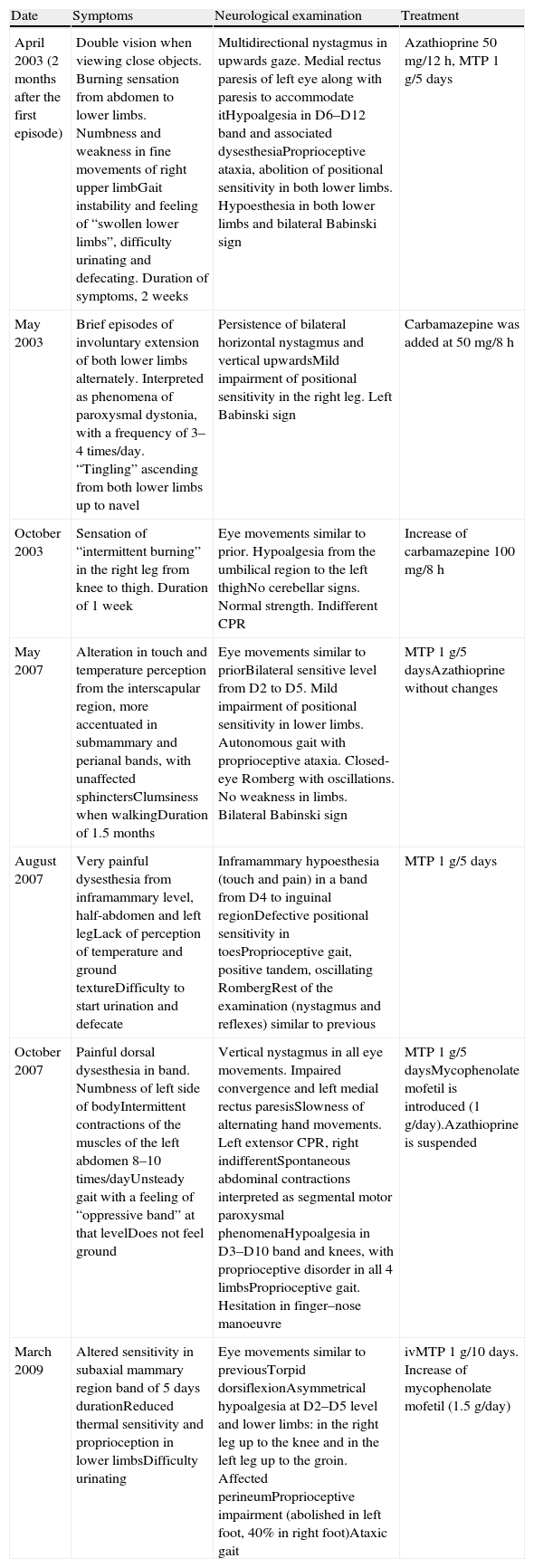

Clinical recurrences and treatment.

| Date | Symptoms | Neurological examination | Treatment |

| April 2003 (2 months after the first episode) | Double vision when viewing close objects. Burning sensation from abdomen to lower limbs. Numbness and weakness in fine movements of right upper limbGait instability and feeling of “swollen lower limbs”, difficulty urinating and defecating. Duration of symptoms, 2 weeks | Multidirectional nystagmus in upwards gaze. Medial rectus paresis of left eye along with paresis to accommodate itHypoalgesia in D6–D12 band and associated dysesthesiaProprioceptive ataxia, abolition of positional sensitivity in both lower limbs. Hypoesthesia in both lower limbs and bilateral Babinski sign | Azathioprine 50mg/12h, MTP 1g/5 days |

| May 2003 | Brief episodes of involuntary extension of both lower limbs alternately. Interpreted as phenomena of paroxysmal dystonia, with a frequency of 3–4 times/day. “Tingling” ascending from both lower limbs up to navel | Persistence of bilateral horizontal nystagmus and vertical upwardsMild impairment of positional sensitivity in the right leg. Left Babinski sign | Carbamazepine was added at 50mg/8h |

| October 2003 | Sensation of “intermittent burning” in the right leg from knee to thigh. Duration of 1 week | Eye movements similar to prior. Hypoalgesia from the umbilical region to the left thighNo cerebellar signs. Normal strength. Indifferent CPR | Increase of carbamazepine 100mg/8h |

| May 2007 | Alteration in touch and temperature perception from the interscapular region, more accentuated in submammary and perianal bands, with unaffected sphinctersClumsiness when walkingDuration of 1.5 months | Eye movements similar to priorBilateral sensitive level from D2 to D5. Mild impairment of positional sensitivity in lower limbs. Autonomous gait with proprioceptive ataxia. Closed-eye Romberg with oscillations. No weakness in limbs. Bilateral Babinski sign | MTP 1g/5 daysAzathioprine without changes |

| August 2007 | Very painful dysesthesia from inframammary level, half-abdomen and left legLack of perception of temperature and ground textureDifficulty to start urination and defecate | Inframammary hypoesthesia (touch and pain) in a band from D4 to inguinal regionDefective positional sensitivity in toesProprioceptive gait, positive tandem, oscillating RombergRest of the examination (nystagmus and reflexes) similar to previous | MTP 1g/5 days |

| October 2007 | Painful dorsal dysesthesia in band. Numbness of left side of bodyIntermittent contractions of the muscles of the left abdomen 8–10 times/dayUnsteady gait with a feeling of “oppressive band” at that levelDoes not feel ground | Vertical nystagmus in all eye movements. Impaired convergence and left medial rectus paresisSlowness of alternating hand movements. Left extensor CPR, right indifferentSpontaneous abdominal contractions interpreted as segmental motor paroxysmal phenomenaHypoalgesia in D3–D10 band and knees, with proprioceptive disorder in all 4 limbsProprioceptive gait. Hesitation in finger–nose manoeuvre | MTP 1g/5 daysMycophenolate mofetil is introduced (1g/day).Azathioprine is suspended |

| March 2009 | Altered sensitivity in subaxial mammary region band of 5 days durationReduced thermal sensitivity and proprioception in lower limbsDifficulty urinating | Eye movements similar to previousTorpid dorsiflexionAsymmetrical hypoalgesia at D2–D5 level and lower limbs: in the right leg up to the knee and in the left leg up to the groin. Affected perineumProprioceptive impairment (abolished in left foot, 40% in right foot)Ataxic gait | ivMTP 1g/10 days. Increase of mycophenolate mofetil (1.5g/day) |

CPR: cutaneous-plantar reflex; MTP: methylprednisolone.

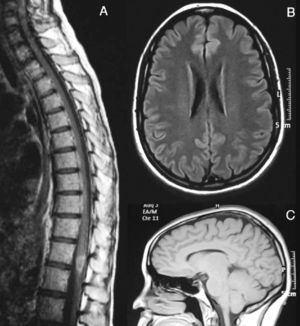

August 2007. (A) Medullar MRI image with intravenous gadolinium. There is a hypodense lesion in T1 sequences, from C2 to D10, with contrast uptake at the level of D8–D9. At the brain level, axial FLAIR (B) and sagittal T1 (C) sequences show no white matter lesions or signs of atrophy.

The patient was chronically treated with azathioprine at doses of 50mg/12h and, given the persistence of relapses, azathioprine was replaced by mycophenolate mofetil at doses of 1–1.5g/day. At present, the patient has not suffered relapses for 3 years, she can walk and jump normally and exploration has only revealed the persistence of upwards vertical and bilateral horizontal nystagmus, without functional interference.

DiscussionThis case suggests a form of recurrent rhombencephalomyelitis compatible with ADEM-R by clinical and radiological criteria, with a good clinical course and therapeutic response to immunosuppressors. At present, the patient is clinically asymptomatic after 7 relapses, despite having presented moderate disability during 3 of them. Notably, all relapses were in the same location as the initial event, although with different severity, and only the first relapse could be attributed to the gradual withdrawal of glucocorticoids.

Images from the brain and medullar MRI scans were extensive, with medullar thickening similar to that described in exceptional cases of ADEM,2,10 and unusual for MS. The medullar images captured contrast on at least 2 occasions, coinciding with an exacerbation of symptoms. It is striking that after 7 recurrences, there were no observations of medullar necrosis or black holes in the brain MRI, suggesting the absence of axonal lesions, more typical in MS. The evolution of the case and the data presented excluded the diagnosis of MS.22

The boundary with NMO is even more controversial.23 From the clinical standpoint, our patient did not present the visual symptoms typical of NMO at any time during her evolution, and her evoked potentials were normal. Full recovery of the episodes without disability is rare in NMO.15,19,23,24 Although in our patient the medullar images resembled those described for NMO,24 they did not show evidence of tissue necrosis, as is usual in NMO.15,24 Nevertheless, there have recently been reports of cases in which radiographic abnormalities improved or even disappeared between episodes.20 The determination of IgG versus AQP4 was negative, although this determination was conducted under immunosuppressive treatment, so we cannot definitively rule out the possibility that our patient suffered an uncommon form of recurrent NMO according to the current criteria.20,24

The clinical evolution and negative result of microbiological and immunological tests conducted at the onset and during several of the episodes excluded other entities which could mimic these symptoms.

There is no clear consensus regarding treatment. During the initial outbreak, the patient was treated with ivMTP at high doses. Due to the severity of the outbreak and the incomplete response, she was subsequently treated with plasmapheresis and iv Ig, with marked clinical improvement.16,17 Treatment with azathioprine was established after the first relapse, following reports of good response to this drug.12,24,25 The outbreaks persisted, so it was switched to mycophenolate mofetil, useful in other autoimmune diseases including NMO and MS.25 This drug acts by inducing apoptosis of reactive T cells and decreasing humoral reactivity.26 The patient has remained asymptomatic for two and a half years.

ConclusionsOur study illustrates the observation that in certain cases of demyelinating diseases, diagnostic characterisation is not easy, despite the current criteria. We believe that our case presents clinical and radiological data matching both adult onset ADEM-R and an unusual form of NMO. The excellent medium-term prognosis with immunosuppressive therapy is more suggestive of a rare form of ADEM-R. Treatment with mycophenolate mofetil may be an alternative therapy for these patients.

FinancingThis article has not been elaborated with any external financing.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: García Domínguez JM, et al. ¿Rombencefalomielitis aguda recurrente del adulto o neuromielitis óptica? A propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2012;27: 154–60.