We describe the key diagnostic and pathophysiological features of supplementary motor area (SMA) syndrome and the factors associated with good prognosis through 2 case reports.

SMA syndrome appears in patients undergoing surgery in areas close to the dorsomedial frontal lobe or SMA; it is characterised by immediate, transient contralateral motor deficits and may also be associated with language impairment.1,2

Although the incidence of SMA syndrome is approximately 50% of all cases of tumours at this location,1–3 and surgical treatment of parasagittal lesions is relatively frequent, SMA syndrome is extremely rare after surgery for extra-axial tumours.1,4–6

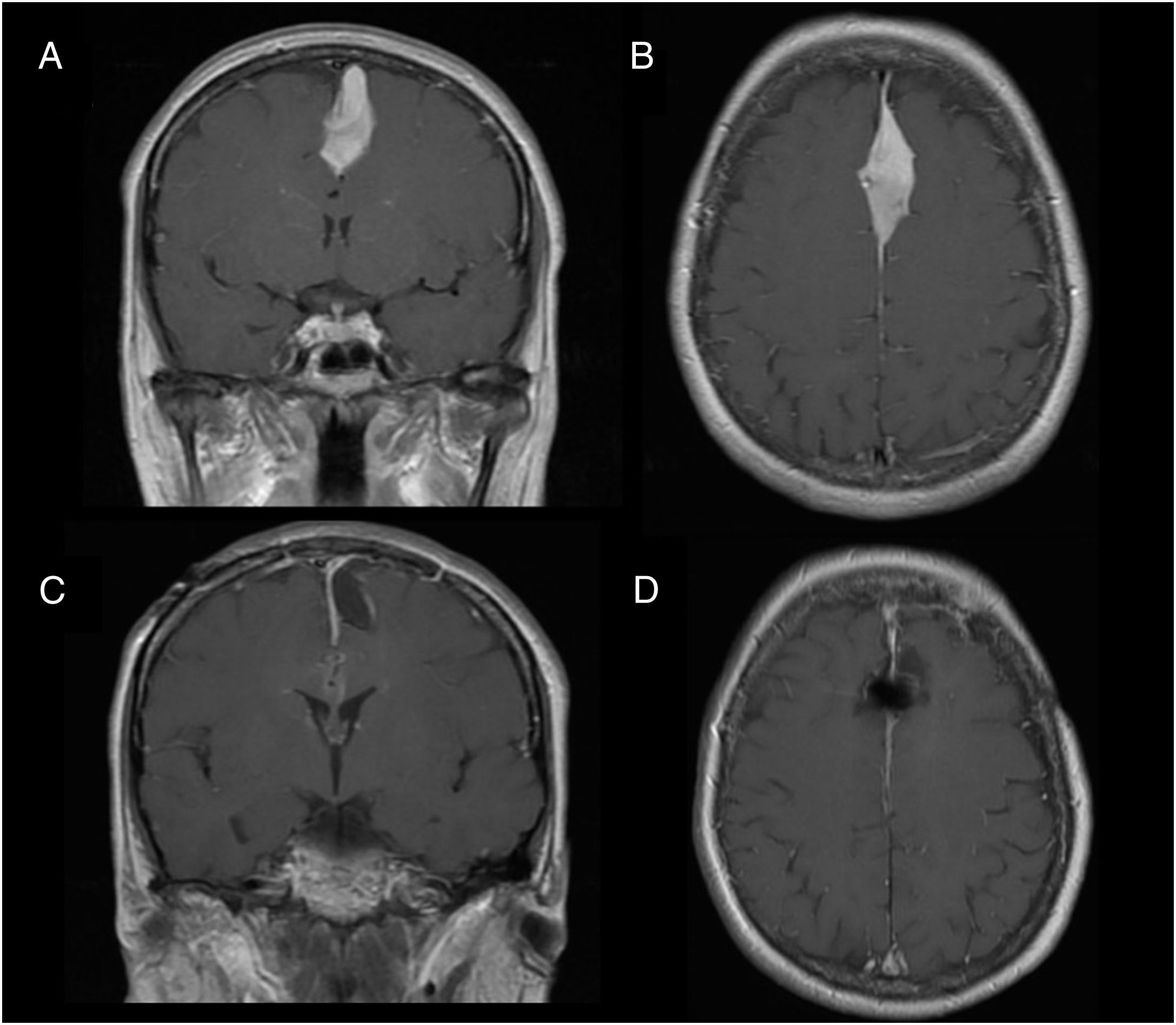

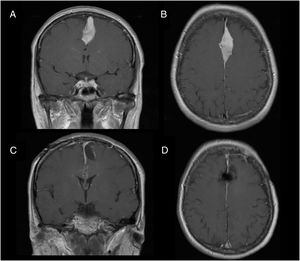

Illustrative case reportsPatient 1Our first patient was a 48-year-old woman with history of parasagittal meningioma; she had undergone surgery 10 years previously and subsequently presented tumour recurrence (Fig. 1A and B). The lesion was completely resected (Fig. 1C and D). After the procedure, the patient presented global aphasia and right hemiparesis (muscle strength 2/5). After a week receiving physical rehabilitation and speech therapy, she recovered strength in the right arm (5/5) and leg (4/5). Dysphasia resolved on day 6. Three weeks after the intervention, the patient was able to walk independently and had resumed work (modified Rankin Scale score of 0); she displayed 5/5 strength in all muscle groups.

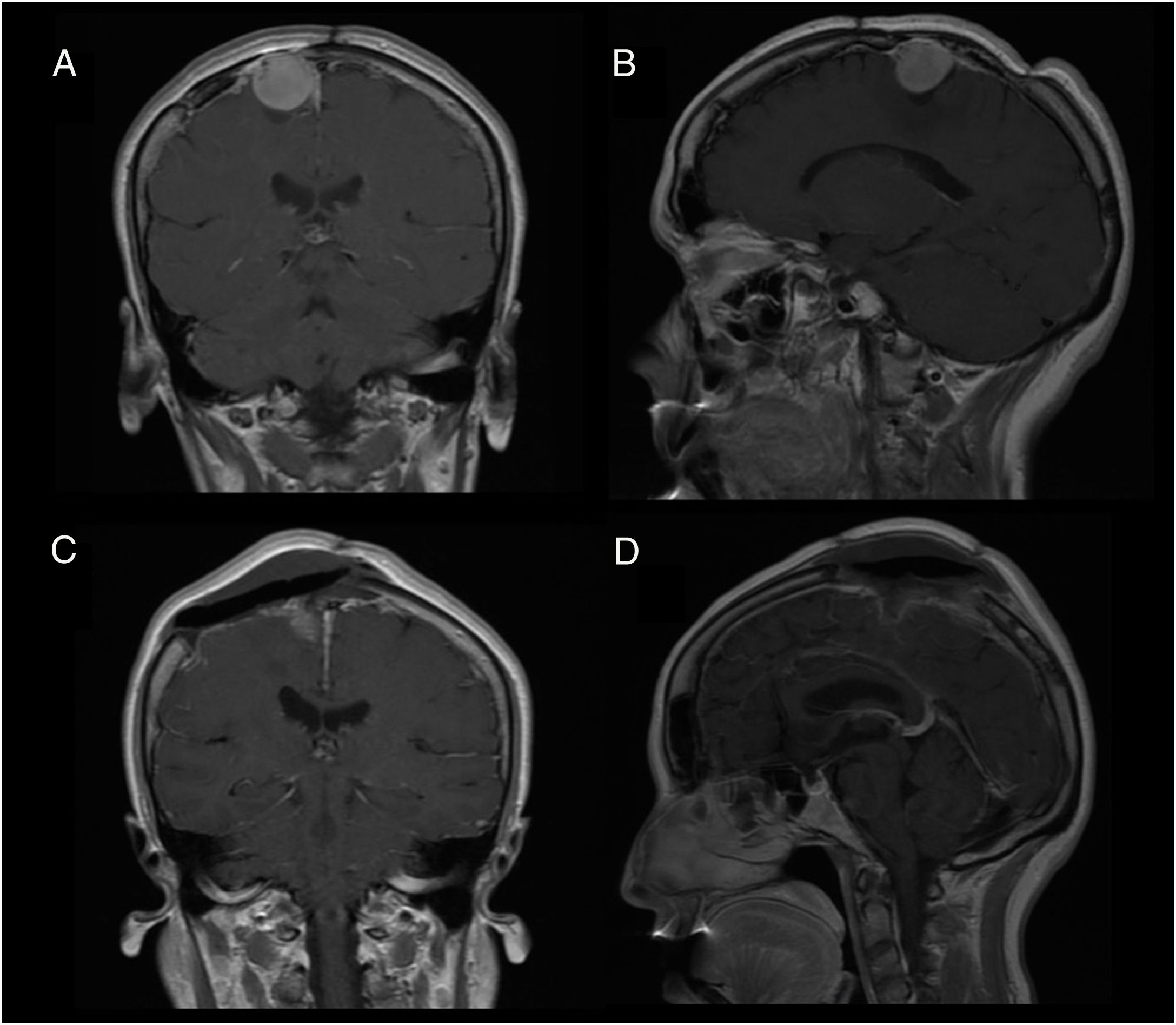

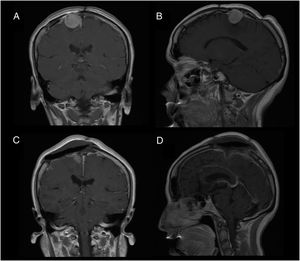

Patient 2Our second patient was a 49-year-old woman with history of interhemispheric meningioma, which was treated surgically 20 years previously. She underwent surgery after presenting tumour recurrence (Fig. 2A and B); the procedure was uneventful and complete tumour resection was achieved (Fig. 2C and D). Upon awakening, the patient presented normal consciousness but was unable to move the left side of her body (muscle strength 1/5). CT angiography ruled out complications of venous drainage. After a short rehabilitation period, the patient recovered baseline muscle strength (5/5); she was discharged after 10 days with no other complications.

DiscussionSurgery to the SMA may cause contralateral motor deficits and motor aphasia (the latter may appear when surgery is performed on the dominant hemisphere).4 Unlike lesions to the pyramidal tract, SMA syndrome is transient and has good prognosis, and patients do not lose muscle tone.6 This syndrome is distinct from the progressive, irreversible deficits that appear 24-48 hours after the procedure due to venous infarction secondary to a lesion to a parasagittal draining vein.6

SMA syndrome is extremely rare after surgery for parasagittal meningioma.1,6 The pathophysiological mechanism is yet to be understood. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and include local oedema, use of retractors, microvascular damage, and resection of healthy parenchyma. Studies using functional MRI scans support the idea that the transient nature of SMA syndrome is due to neuronal plasticity.7,8

The cases presented here are representative in that the patients presented SMA syndrome after surgical treatment of a recurrent tumour. Abel et al.7 reported 6 cases of intra-axial tumours located in the SMA that progressed with recurrent SMA syndrome after repeat surgery; this supports the hypothesis of neuronal reorganisation in the SMA around the previously resected areas.4 In the case of extra-axial tumours, where ideally no healthy parenchyma is resected, the hypothesis of neuronal plasticity does not seem to be plausible. We concur with Berg et al.,6 who argue that surgical manipulation is the main cause of SMA syndrome. This is particularly relevant in cases of more aggressive tumours or tumour recurrence, where preservation of the arachnoid mater is more challenging from a technical viewpoint.4 This suggests a certain predisposition to SMA syndrome among patients with history of surgery, who probably already present arachnoid damage, with symptoms triggered after repeat surgery.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Pérez R, Vergara C, Rayo N, Mura J. Recurrencia del síndrome de área motora suplementaria en meningiomas parasagitales recidivados: del evento al origen. Neurología. 2020;35:606–608.