Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a disorder characterised by an irresistible urge to move the legs, usually accompanied by unpleasant sensations. It is more frequent in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) than in the general population.

ObjectivesTo evaluate the prevalence of RLS, defined according to the 4 essential requirements included in the diagnostic criteria proposed by the International Restless Leg Syndrome Study Group, in a cohort of patients with MS; and to identify potential risk factors and the clinical impact of RLS.

ResultsThe sample included 120 patients with MS, with a mean age of symptom onset of 40 years and an average disease duration of 46 months. The prevalence rate of RLS was 23.3%. MS progression time was significantly shorter in patients with RLS (P=.001). A recent relapse, and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and neuropathic pain were significantly associated with risk of RLS (P=.001, P<.001, P<.001, and P=.001, respectively). In addition, patients with RLS had a greater risk of poor sleep quality, fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and poor quality of life than those without RLS (P=.002, P=.017, P=.013, and P=.009, respectively).

ConclusionsRLS should be considered in the neurological evaluation of patients with MS; early diagnosis and treatment would improve the quality of life of patients with MS presenting RLS.

El síndrome de piernas inquietas (SPI) es un trastorno caracterizado por la necesidad imperiosa de mover las piernas, estando a menudo acompañado de sensaciones desagradables. Su frecuencia es superior en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple (EM) que en la población general.

ObjetivosEvaluar la prevalencia del SPI, según el cumplimiento de los 4 requisitos esenciales incluidos en los criterios diagnósticos propuestos por la International Restless Leg Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG, 2003), en una cohorte de pacientes con EM e identificar posibles factores de riesgo y repercusión clínica.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 120 pacientes con EM, con una edad media de inicio de 40 años y un tiempo medio de evolución de 46 meses. La prevalencia de SPI, según el cumplimiento de criterios diagnósticos de la IRLSSG, fue del 23,3%. El tiempo de evolución de EM, desde la aparición de los primeros síntomas, fue significativamente menor en pacientes con SPI (p=0,001). La presencia de un brote reciente, así como de síntomas de ansiedad, depresión y dolor neuropático se asociaron de forma significativa con el riesgo de SPI (p=0,001, p<0,001, p<0,001 y p=0,001, respectivamente). Además, los pacientes con SPI y EM presentaron mayor riesgo de mala calidad de sueño, fatiga, somnolencia diurna y peor calidad de vida, que aquellos sin SPI (p=0,002, p=0,017, p=0,013 y p=0,009, respectivamente).

ConclusionesEl SPI debe ser considerado en la evaluación neurológica de pacientes con EM, cuyo diagnóstico y tratamiento precoz mejoraría la calidad de vida de estos sujetos.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most frequent chronic, multifocal, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system.1 It affects young adults, representing the second most frequent cause of disability in this population group.2 Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location of the lesions along the neuraxis.3 However, other symptoms cannot be localised, and are thought to have a multifactorial origin. These include cognitive impairment, pain, fatigue, and restless legs syndrome (RLS).4,5

RLS is a frequent disorder, with prevalence ranging from 4% to 10% in the general population,5,6 characterised by an uncontrollable urge to move the legs, generally accompanied by pain or discomfort. Symptoms present during periods of inactivity, predominantly at night, and improve with movement. The pathogenesis of RLS is unclear. The disorder is currently classified as idiopathic (familial or sporadic) or secondary (associated with conditions that induce iron deficiency or alterations in iron metabolism, pregnancy, chronic kidney disease, Parkinson's disease, etc).

The prevalence of RLS in patients with MS ranges from 12.1% to 57.5%, depending on the series.7–15 However, while numerous studies have reported higher prevalence among patients with MS, multiple sclerosis has yet not been considered a secondary cause of RLS.

In recent years, several studies have focused on identifying risk factors for RLS in patients with MS and evaluating the impact of the condition. RLS appears to be associated with female sex and older age, although these associations are not statistically significant.11,14,16 RLS has also been associated with more severe disability, particularly in patients with pyramidal and sensory involvement.11,17 Depression and anxiety are also considered risk factors for RLS in patients with MS.7 Greater use of antidepressants has been observed in patients with MS and RLS than in those without RLS.11 However, other researchers have been unable to replicate this finding.9 Furthermore, studies have consistently shown a higher prevalence of insomnia and daytime sleepiness among patients with MS and RLS.11

Despite growing interest in the potential association between RLS and MS, only one study to date has addressed this topic in our setting, and was unable to confirm the association.18 In this context, we aimed to analyse the prevalence of RLS in a cohort of Spanish patients with MS attended at our centre. This study also aims to evaluate the severity of RLS, to identify risk factors for RLS in patients with MS, and to analyse the clinical impact of the syndrome in these patients.

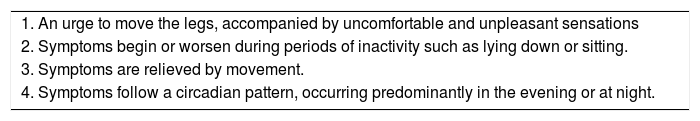

Patients and methodsWe conducted an observational, cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of patients diagnosed with MS according to the 2010 McDonald criteria19 and attended at the demyelinating diseases unit of Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío between October 2014 and April 2016. The study evaluated the prevalence of RLS according to the 4 diagnostic criteria proposed by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) in 2003, which are still in use (Table 1).5

Diagnostic criteria for restless legs syndrome proposed by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group in 2003.

| 1. An urge to move the legs, accompanied by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations |

| 2. Symptoms begin or worsen during periods of inactivity such as lying down or sitting. |

| 3. Symptoms are relieved by movement. |

| 4. Symptoms follow a circadian pattern, occurring predominantly in the evening or at night. |

We included patients with MS of both sexes, aged older than 14 years, and attended at our unit. We excluded patients with a recent diagnosis of MS (< 1month), presenting other neurological comorbidities, receiving dopaminergic or antidopaminergic drugs, or presenting conditions that may cause secondary RLS (iron deficiency, kidney failure, pregnancy, etc). Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and participants signed informed consent forms. The study was approved by our hospital's ethics committee.

During the initial consultation, we administered an ad hoc questionnaire to evaluate potential risk factors for RLS and the clinical impact of the condition. We analysed demographic variables (age at the time of inclusion, sex, tobacco use), MS-related clinical variables (age at disease onset, clinical course of MS, disease duration, occurrence of relapses in the previous 3 months, degree of disability according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), presence of neuropathic pain, corticosteroid treatment in the previous 3 months, disease-modifying treatments and administration schedule), and clinical variables associated with mood disorders. Severity of neuropathic pain was evaluated with a visual analogue scale, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst imaginable pain. Mood disorders were evaluated with the Beck Depression Inventory20 (cut-off score, 14 points) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory21 (cut-off score, 21 points). We also gathered data on the use of psychoactive drugs.

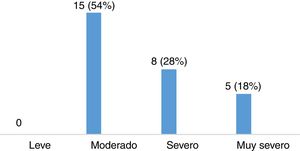

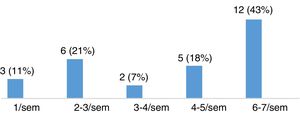

We evaluated the clinical impact of RLS using the International RLS Rating Scale,22,23 which assesses the subjective symptoms of RLS. The scale includes 10 items, each of which is scored from 0 to 4, and enquires about the following aspects: (1) severity of discomfort in legs and arms, (2) need to move around, (3) relief with movement, (4) sleep disturbances due to RLS, (5) fatigue and daytime sleepiness due to RLS, (6) severity of RLS, (7) symptom frequency, (8) duration of symptoms throughout the day, (9) impact of symptoms on daily activities, and (10) impact of symptoms on mood. Total score ranges from 0 to 40 points, and RLS is classified as mild (1-10 points), moderate (11-20), severe (21-–30), or very severe (31-40). We also recorded the weekly frequency of symptoms of RLS.

To analyse the impact of RLS on sleep, we used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)24; scores ≥ 5 points indicate poor sleep quality. Presence of excessive daytime sleepiness was evaluated with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS; cut-off score, 11 points).25 To detect fatigue, we used the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS; cut-off score, 38 points).26 Lastly, the impact of RLS on quality of life was analysed with the EuroQol-5D quality of life scale (EQ-5D),27 which evaluates 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression).

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics software, version 19. Continuous variables following a normal distribution are expressed as means and standard deviation (SD), whereas non–normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as medians and the 25th and 75th percentiles (p25-p75). Qualitative variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. We compared different demographic and clinical variables between patients with MS with and without RLS using the chi-square test for qualitative variables, the t test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test for non–normally distributed continuous variables. We calculated odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the variables identified as risk factors for RLS using a Cox univariate regression analysis. Lastly, to define the factors independently associated with RLS in patients with MS, we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis (Wald backward elimination) incorporating the variables showing a significant association in the univariate model. For all analyses, statistical significance was set at P<.05.

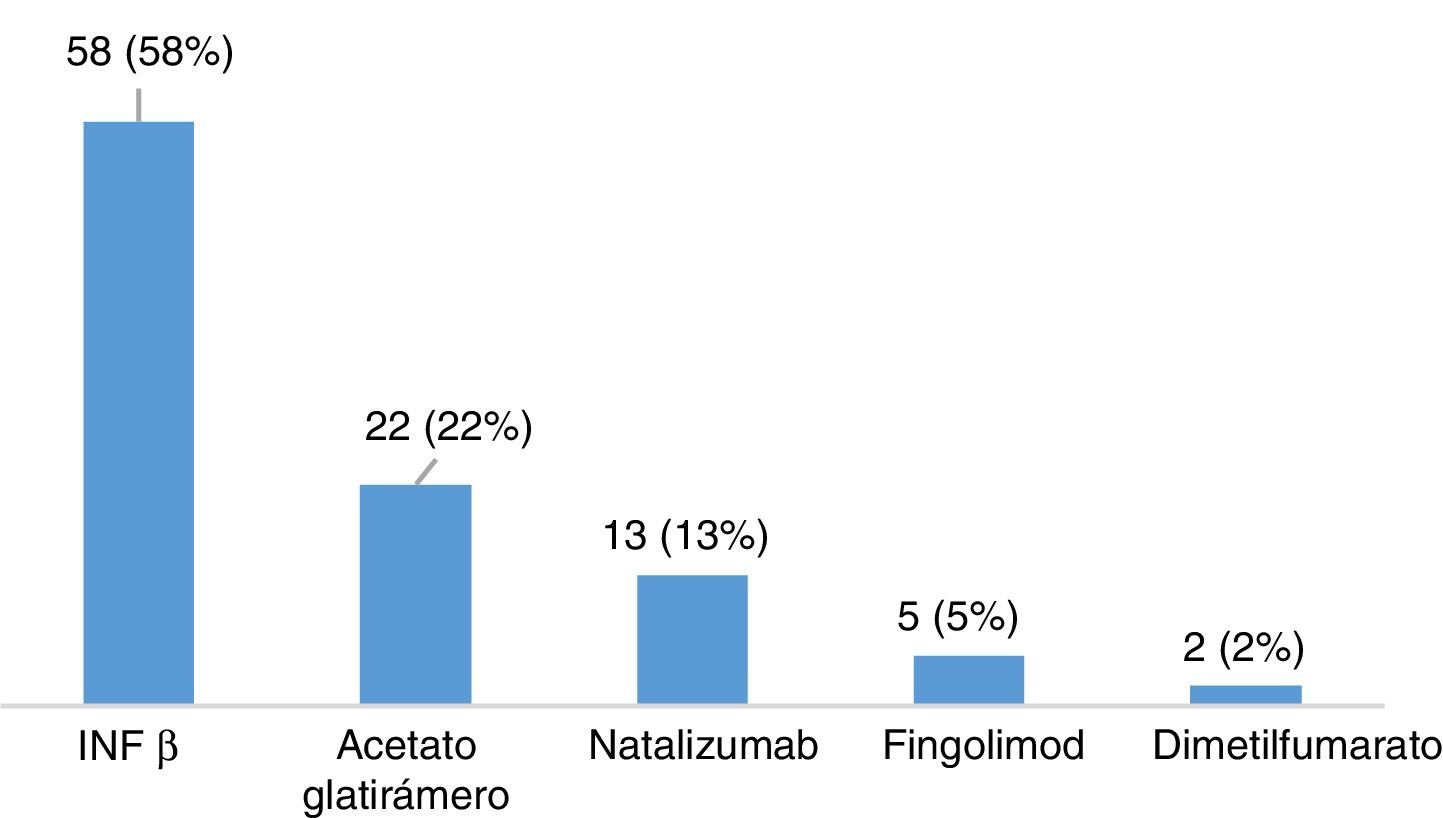

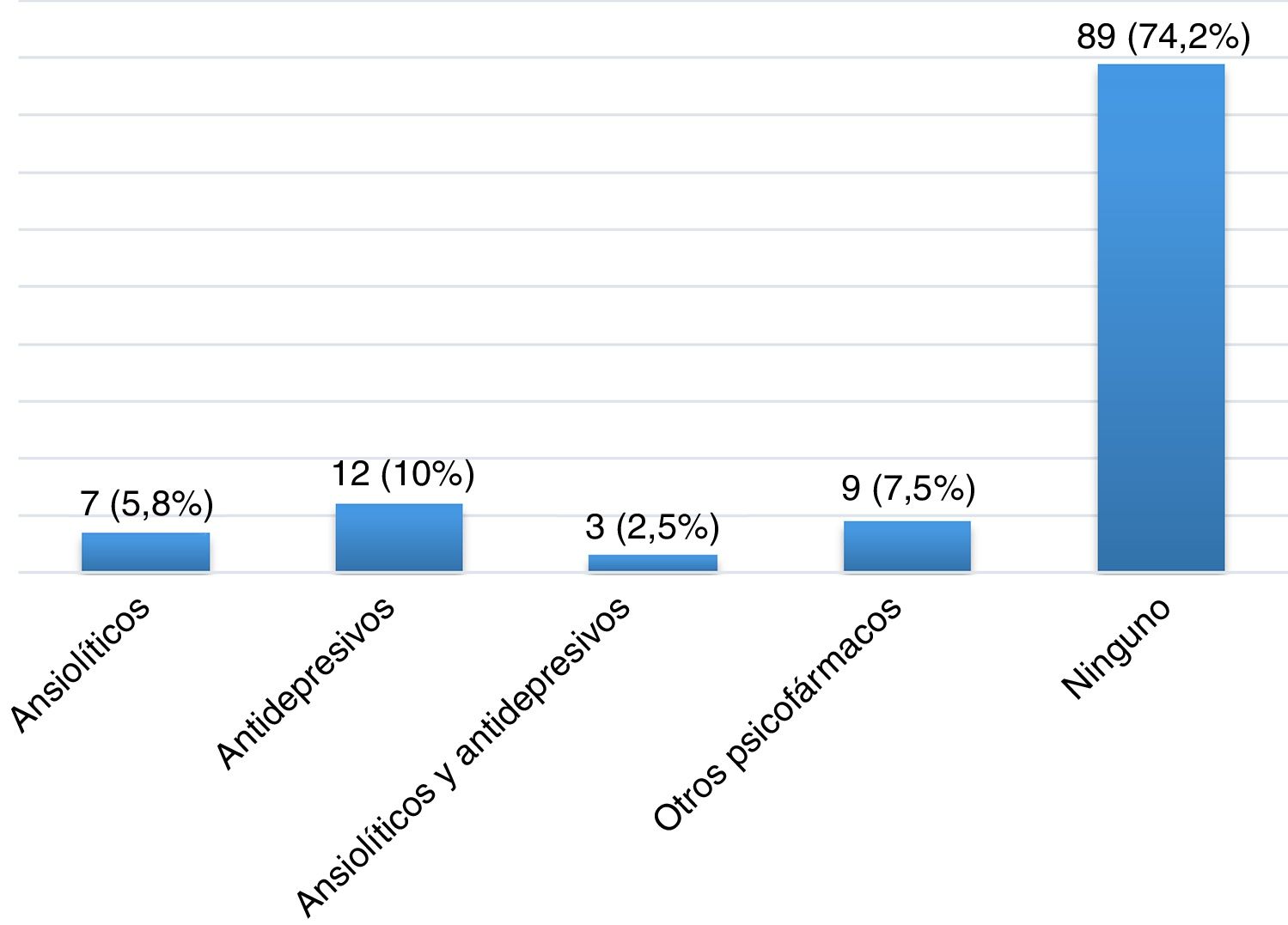

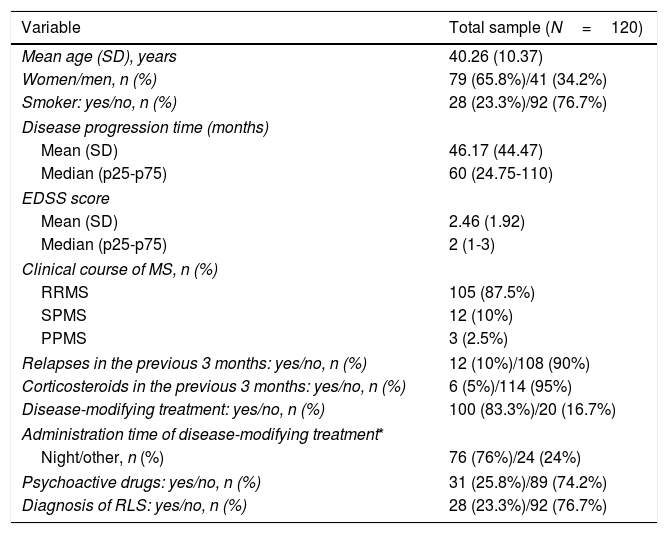

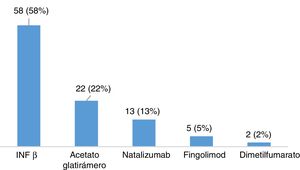

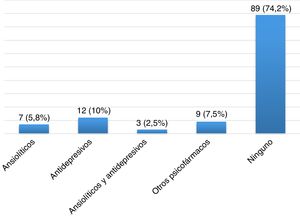

ResultsDescription of the sample and prevalence of restless legs syndromeOur sample included 120 patients with MS, most of whom were women (65.8%), with a mean (SD) age of 40.26 (10.37) years and a mean disease progression time of 46.17 (44.47) months at the time of inclusion (Table 2). Twenty-eight patients (23.3%) were smokers. A total of 105 patients (87.5%) had relapsing-remitting MS, 12 (10%) had secondary progressive MS, and 3 (2.5%) had primary progressive MS. Mean EDSS score at the time of inclusion was 2.46 (1.92). Twelve patients (10%) had presented relapses in the 3 months prior to inclusion in the study, 6 of whom were receiving corticosteroids. One hundred patients (83.3%) were taking disease-modifying drugs (Fig. 1), at night in most cases (76%), and 31 (25.83%) were receiving psychoactive drugs (Fig. 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of our sample.

| Variable | Total sample (N=120) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 40.26 (10.37) |

| Women/men, n (%) | 79 (65.8%)/41 (34.2%) |

| Smoker: yes/no, n (%) | 28 (23.3%)/92 (76.7%) |

| Disease progression time (months) | |

| Mean (SD) | 46.17 (44.47) |

| Median (p25-p75) | 60 (24.75-110) |

| EDSS score | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.46 (1.92) |

| Median (p25-p75) | 2 (1-3) |

| Clinical course of MS, n (%) | |

| RRMS | 105 (87.5%) |

| SPMS | 12 (10%) |

| PPMS | 3 (2.5%) |

| Relapses in the previous 3 months: yes/no, n (%) | 12 (10%)/108 (90%) |

| Corticosteroids in the previous 3 months: yes/no, n (%) | 6 (5%)/114 (95%) |

| Disease-modifying treatment: yes/no, n (%) | 100 (83.3%)/20 (16.7%) |

| Administration time of disease-modifying treatment* | |

| Night/other, n (%) | 76 (76%)/24 (24%) |

| Psychoactive drugs: yes/no, n (%) | 31 (25.8%)/89 (74.2%) |

| Diagnosis of RLS: yes/no, n (%) | 28 (23.3%)/92 (76.7%) |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS: multiple sclerosis; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RLS: restless legs syndrome; RRMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SD: standard deviation; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

The prevalence rate of RLS in our sample (patients meeting all 4 IRLSSG diagnostic criteria5) was 23.3% (28 cases).

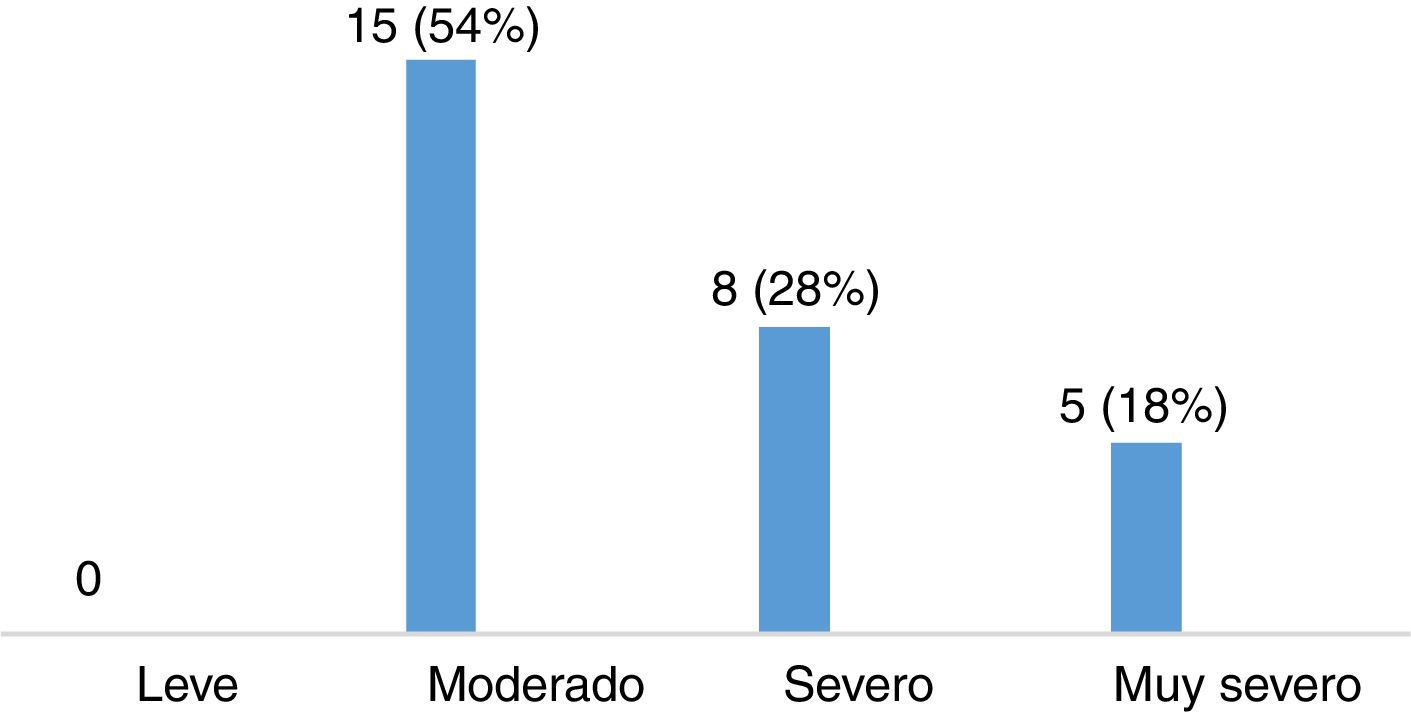

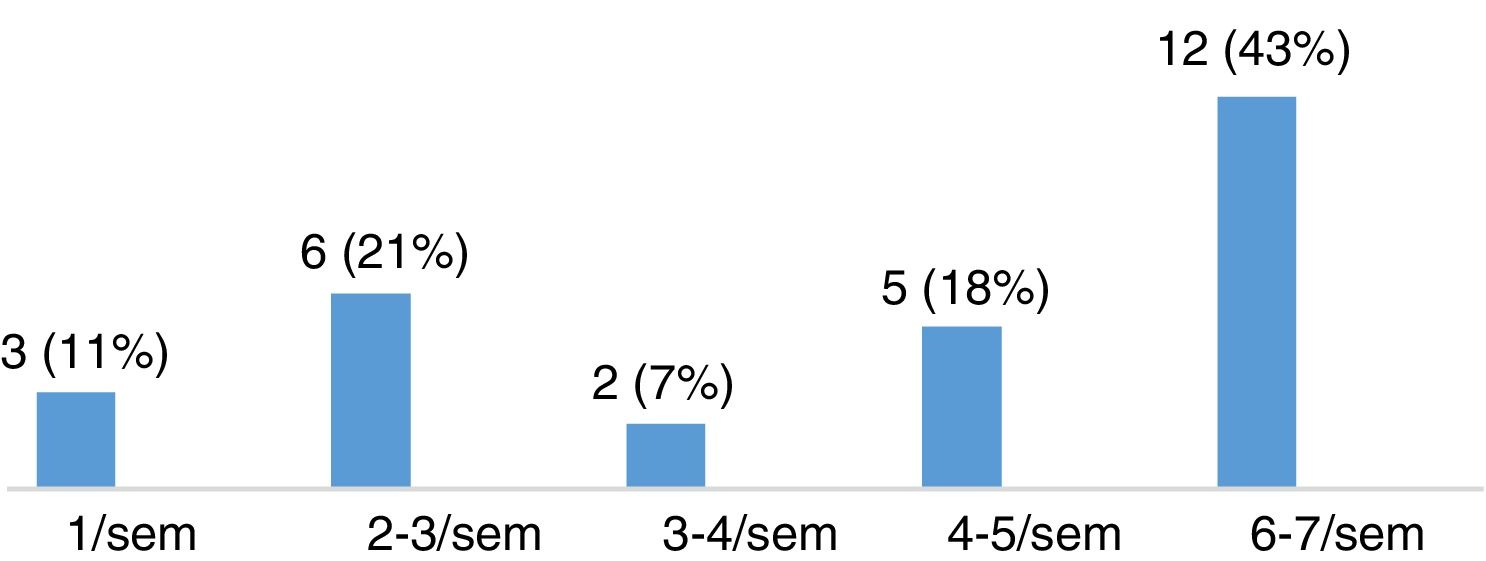

Severity of restless legs syndrome in patients with multiple sclerosisThe group of patients with MS and RLS (n=28) scored a mean (SD) of 22.11 (8.01) points on the International RLS Rating Scale. Fifteen of these patients (53.57%) presented moderate RLS, 8 (28.57%) had severe RLS, and 5 (17.86%) had very severe RLS (Fig. 3). Most patients presented symptoms of RLS on a daily basis, as shown in Fig. 4.

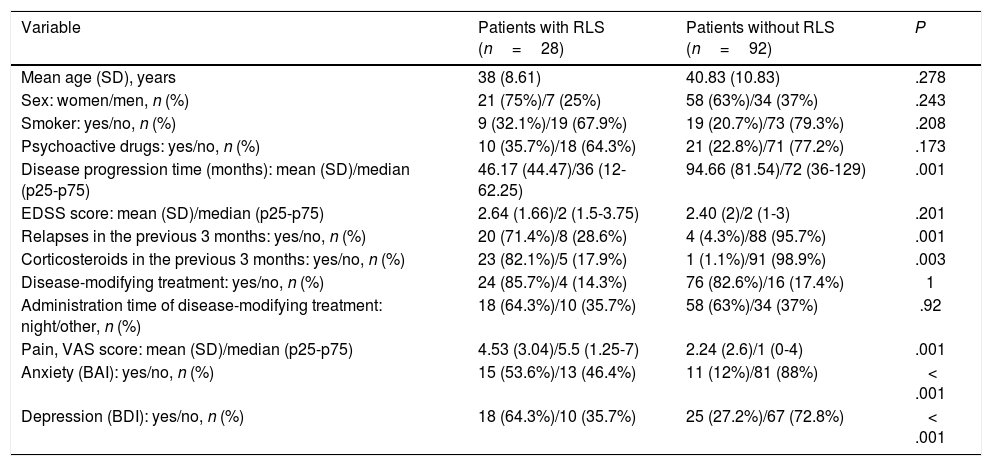

Potential risk factors for restless legs syndrome in patients with multiple sclerosisNo statistically significant differences were observed between patients with and without RLS in terms of age (P=.278), sex (P=.243), tobacco use (P=.208), or use of psychoactive drugs (P=.173) (Table 3).

Analysis of demographic and clinical variables potentially constituting risk factors for RLS in patients with MS.

| Variable | Patients with RLS (n=28) | Patients without RLS (n=92) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 38 (8.61) | 40.83 (10.83) | .278 |

| Sex: women/men, n (%) | 21 (75%)/7 (25%) | 58 (63%)/34 (37%) | .243 |

| Smoker: yes/no, n (%) | 9 (32.1%)/19 (67.9%) | 19 (20.7%)/73 (79.3%) | .208 |

| Psychoactive drugs: yes/no, n (%) | 10 (35.7%)/18 (64.3%) | 21 (22.8%)/71 (77.2%) | .173 |

| Disease progression time (months): mean (SD)/median (p25-p75) | 46.17 (44.47)/36 (12-62.25) | 94.66 (81.54)/72 (36-129) | .001 |

| EDSS score: mean (SD)/median (p25-p75) | 2.64 (1.66)/2 (1.5-3.75) | 2.40 (2)/2 (1-3) | .201 |

| Relapses in the previous 3 months: yes/no, n (%) | 20 (71.4%)/8 (28.6%) | 4 (4.3%)/88 (95.7%) | .001 |

| Corticosteroids in the previous 3 months: yes/no, n (%) | 23 (82.1%)/5 (17.9%) | 1 (1.1%)/91 (98.9%) | .003 |

| Disease-modifying treatment: yes/no, n (%) | 24 (85.7%)/4 (14.3%) | 76 (82.6%)/16 (17.4%) | 1 |

| Administration time of disease-modifying treatment: night/other, n (%) | 18 (64.3%)/10 (35.7%) | 58 (63%)/34 (37%) | .92 |

| Pain, VAS score: mean (SD)/median (p25-p75) | 4.53 (3.04)/5.5 (1.25-7) | 2.24 (2.6)/1 (0-4) | .001 |

| Anxiety (BAI): yes/no, n (%) | 15 (53.6%)/13 (46.4%) | 11 (12%)/81 (88%) | < .001 |

| Depression (BDI): yes/no, n (%) | 18 (64.3%)/10 (35.7%) | 25 (27.2%)/67 (72.8%) | < .001 |

BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; RLS: restless legs syndrome; SD: standard deviation; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

Regarding clinical variables, no significant differences were observed between patients with different clinical courses of MS. Disease progression time was significantly shorter in the group of patients with RLS (P=.001), but the OR was close to 1 (OR: 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97-0.99). EDSS scores were higher in the group of patients with RLS, although this difference was not statistically significant. Occurrence of relapses in the 3 months prior to inclusion in the study was significantly associated with risk of RLS (P=.001; OR: 8.8; 95% CI, 2.21-32.1), as was the use of corticosteroids in the previous 3 months (P=.003). We were unable to calculate the OR for corticosteroid use due to the small number of patients included in some of the analysis subgroups, which resulted in great dispersion of the data. Lastly, use of disease-modifying drugs and administration at night were not correlated with increased risk of RLS (P=1 and P=.92, respectively) (Table 3).

We also evaluated mood disorders and neuropathic pain as other potential independent risk factors for RLS. Higher scores on the Beck Anxiety Inventory (P<.001; OR: 8.49; 95% CI, 3.2-22.49) and the Beck Depression Inventory (P<.001; OR: 4.82; 95% CI, 1.96-11.85) were significantly correlated with higher risk of presenting RLS. We also observed a significant correlation between presence of RLS and pain as measured with the visual analogue scale (P=.001; OR: 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53).

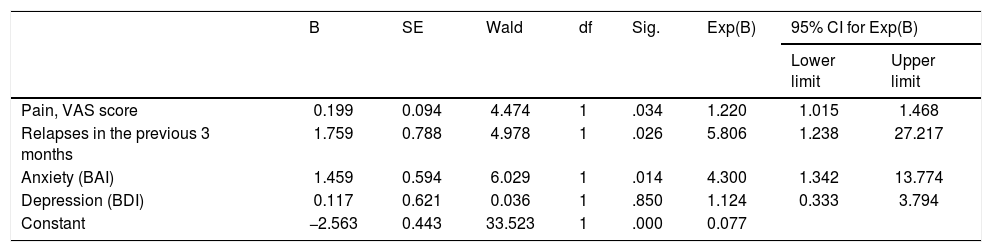

The multivariate logistic regression analysis used to create a predictive model of RLS in patients with MS included the variables “relapses in the 3 previous months,” “anxiety,” “depression,” and “pain,” which had all demonstrated a significant association with RLS in the univariate analysis. Of these, anxiety, occurrence of relapses in the previous 3 months, and severe pain were identified as independent predictors of RLS in patients with MS (P=.014, P=.026, and P=.034, respectively) (Table 4).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of independent predictors of RLS in patients with MS.

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| Pain, VAS score | 0.199 | 0.094 | 4.474 | 1 | .034 | 1.220 | 1.015 | 1.468 |

| Relapses in the previous 3 months | 1.759 | 0.788 | 4.978 | 1 | .026 | 5.806 | 1.238 | 27.217 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | 1.459 | 0.594 | 6.029 | 1 | .014 | 4.300 | 1.342 | 13.774 |

| Depression (BDI) | 0.117 | 0.621 | 0.036 | 1 | .850 | 1.124 | 0.333 | 3.794 |

| Constant | −2.563 | 0.443 | 33.523 | 1 | .000 | 0.077 | ||

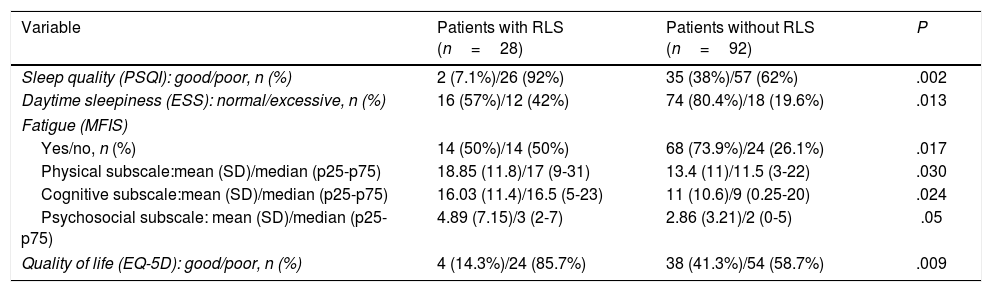

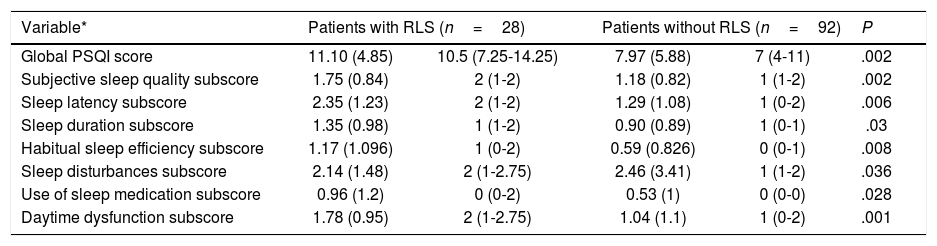

We observed statistically significant differences in sleep quality between patients with and without RLS. Global PSQI scores showed that poor sleep quality was significantly more frequent among patients with RLS than among those without the disorder (P=.002) (Table 5). As shown in Table 6, patients with MS and RLS scored significantly higher on all components of the PSQI except for “sleep disturbances.” According to the ESS, patients with MS and RLS presented greater daytime sleepiness (P=.013). Fatigue was also associated with presence of RLS, according to both global MFIS scores (P=.017) and to physical (P=.03), cognitive (P=.024), and psychosocial subscale scores (P=.05). Lastly, EQ-5D questionnaire scores revealed significantly poorer quality of life in patients with MS and RLS (P=.009) (Table 5).

Comparison of variables with clinical impact on the quality of life of patients with MS between patients with and without RLS.

| Variable | Patients with RLS (n=28) | Patients without RLS (n=92) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality (PSQI): good/poor, n (%) | 2 (7.1%)/26 (92%) | 35 (38%)/57 (62%) | .002 |

| Daytime sleepiness (ESS): normal/excessive, n (%) | 16 (57%)/12 (42%) | 74 (80.4%)/18 (19.6%) | .013 |

| Fatigue (MFIS) | |||

| Yes/no, n (%) | 14 (50%)/14 (50%) | 68 (73.9%)/24 (26.1%) | .017 |

| Physical subscale:mean (SD)/median (p25-p75) | 18.85 (11.8)/17 (9-31) | 13.4 (11)/11.5 (3-22) | .030 |

| Cognitive subscale:mean (SD)/median (p25-p75) | 16.03 (11.4)/16.5 (5-23) | 11 (10.6)/9 (0.25-20) | .024 |

| Psychosocial subscale: mean (SD)/median (p25-p75) | 4.89 (7.15)/3 (2-7) | 2.86 (3.21)/2 (0-5) | .05 |

| Quality of life (EQ-5D): good/poor, n (%) | 4 (14.3%)/24 (85.7%) | 38 (41.3%)/54 (58.7%) | .009 |

EQ-5D: EuroQol-5D; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; RLS: restless legs syndrome; SD: standard deviation.

Comparison of PSQI scores between patients with MS with and without RLS.

| Variable* | Patients with RLS (n=28) | Patients without RLS (n=92) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global PSQI score | 11.10 (4.85) | 10.5 (7.25-14.25) | 7.97 (5.88) | 7 (4-11) | .002 |

| Subjective sleep quality subscore | 1.75 (0.84) | 2 (1-2) | 1.18 (0.82) | 1 (1-2) | .002 |

| Sleep latency subscore | 2.35 (1.23) | 2 (1-2) | 1.29 (1.08) | 1 (0-2) | .006 |

| Sleep duration subscore | 1.35 (0.98) | 1 (1-2) | 0.90 (0.89) | 1 (0-1) | .03 |

| Habitual sleep efficiency subscore | 1.17 (1.096) | 1 (0-2) | 0.59 (0.826) | 0 (0-1) | .008 |

| Sleep disturbances subscore | 2.14 (1.48) | 2 (1-2.75) | 2.46 (3.41) | 1 (1-2) | .036 |

| Use of sleep medication subscore | 0.96 (1.2) | 0 (0-2) | 0.53 (1) | 0 (0-0) | .028 |

| Daytime dysfunction subscore | 1.78 (0.95) | 2 (1-2.75) | 1.04 (1.1) | 1 (0-2) | .001 |

PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; RLS: restless legs syndrome; SD: standard deviation.

RLS is common in patients with MS, and may considerably decrease their quality of life. In Spain, only one study has evaluated the prevalence of RLS in patients with MS; the study, conducted in Catalonia, found similar prevalence in patients with MS and in the general population (13.2% vs 9.3%), and with greater prevalence in women than in men.18

However, in line with studies from other independent groups, we found a higher prevalence of RLS in patients with MS than in the general population. We observed a prevalence rate of 23.3% among white patients with MS; this rate is similar to those reported in previous studies.7,9,11,15,16,28,29 Unlike other studies,18,23 ours did not include a control group of healthy individuals; rather, we referred to the reported prevalence rate of RLS in the general population.18,28 In our series, RLS was generally moderate-to-severe, as has also been reported by other researchers.7,10,30

We identified the following risk factors for RLS in our sample: recent history of relapses, shorter disease progression time, mood alterations, and severe pain. No significant differences in RLS prevalence were found in association with age and sex; this is consistent with previous studies.30 Likewise, no association was observed between clinical course of MS and risk of RLS, although we did observe an association with active forms of the disease, as reported in other series.7,11,14,17 RLS was more prevalent among patients presenting recent relapses. In contrast, we found no differences in the degree of disability between patients with and without RLS; this is consistent with results from similar series.9 Some studies have reported a greater risk of RLS in advanced stages of MS.11 However, we observed the opposite in our sample, with higher prevalence of RLS among patients with shorter progression times. This may suggest that RLS will present in the early stages of MS in susceptible patients.

Several studies have suggested that sleep disorders in MS may be explained at least in part by the effects of immunomodulatory drugs (especially when administered at bedtime) and corticosteroids.31,32 However, no study has yet evaluated the impact of these treatments on the risk of RLS in patients with MS. In our study, none of the disease-modifying drugs used by our patients was found to be significantly associated with greater prevalence of RLS. Corticosteroid treatment was associated with increased risk of RLS, but no definitive conclusions can be drawn since the small number of patients included in one of the groups prevented us from completing the confirmatory analysis.

Some mood disorders, including anxiety and depression, are known to be common among individuals with MS.7 In our sample, the prevalence of these mood disorders was higher in patients with RLS, with a close bidirectional relationship whereby patients with MS and more severe depression or anxiety presented a greater risk of developing RLS, and vice versa.7,11

Regarding the clinical impact of RLS, patients with the condition presented poorer sleep quality, more severe fatigue and excessive daytime sleepiness, and poorer quality of life than patients without the condition. Both global PSQI scores and component scores were higher in patients with RLS, with the exception of scores for the “sleep disturbances” component. As this subscale evaluates all kinds of disturbances that may cause night-time awakenings (going to the toilet, coughing, snoring, etc), we may assume that patients with RLS also present other comorbidities potentially causing sleep disturbances that were not included in our analysis. Several authors have reported higher prevalence of fatigue in patients with MS and RLS.7 Our results not only support this association but also reveal that RLS has a substantial impact on all 3 spheres of fatigue (physical, cognitive, and psychosocial subscales). Furthermore, as reported by other researchers,14 RLS is associated with more severe daytime sleepiness. Likewise, self-reported quality of life was significantly poorer in the group of patients with MS and RLS. We may therefore conclude that RLS has a negative impact on quality of life in patients with MS.

Some psychoactive drugs, particularly antidepressants and anxiolytics, are known to worsen the symptoms of RLS.11,33,34 In our sample, however, no significant association was observed between use of these drugs and development of RLS. This may be explained by greater use of psychoactive drugs by patients with MS as compared to the general population due to associated comorbidities that are not addressed in this study. Further research is needed to clarify this issue.

In conclusion, our results confirm the high prevalence of RLS in Spanish patients with MS, based on data from a sample of Andalusian patients with the disease. Our study did not identify any demographic variable or treatment as a risk factor for RLS. However, active forms of MS, with recent relapses, were associated with increased risk of presenting RLS. Mood disorders and presence of neuropathic pain have also been significantly associated with RLS. Lastly, our results also reveal a higher incidence of poor sleep quality, fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and poor quality of life in patients with MS and RLS than in those without RLS. The neurological examination of patients with MS should include screening for RLS to enable early detection and appropriate treatment; this may substantially improve overall quality of life in these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Lebrato Hernández L, Prieto León M, Cerdá Fuentes NA, Uclés Sánchez AJ, Casado Chocán JL, Díaz Sánchez M. Síndrome de piernas inquietas en esclerosis múltiple: evaluación de factores de riesgo y repercusión clínica. Neurología. 2022;37:83–90.