Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), first described in 1881, is caused by thiamine deficiency.1 The classic triad of symptoms is cognitive alterations, oculomotor dysfunction (nystagmus, ophthalmoplegia), and ataxia. Korsakoff syndrome is regarded as the final stage of WE and typically presents with anterograde amnesia and confabulation.2 WE may be associated with other deficiency diseases, such as scurvy, which require a high level of clinical suspicion and early treatment with vitamin supplementation.

We present the case of a 50-year-old female patient, a smoker, who came to the emergency department due to vertigo upon waking and gait instability, with a tendency to veer to the right. According to the patient's family, she had begun to display behavioural alterations a week previously, in the form of repetitive behaviour, confusion, and frequent memory deficits. She was afebrile and presented no other systemic symptoms. Examination of the patient revealed altered mental state (disorientation and confusion), anterograde amnesia, complete ophthalmoplegia of abduction bilaterally, multidirectional nystagmus, ataxic gait, and abolished stretch reflexes in the lower limbs. Suspecting WE, we administered thiamine supplementation and ophthalmoplegia resolved in 24h. A brain MRI scan revealed hyperintensities in the floor of the fourth ventricle, around the aqueduct of Sylvius at the level of the midbrain, the superior colliculus, and also the hypothalamus and medial region of both thalamic nuclei, the mammillary bodies, and the pillars of the fornices; the lesions showed contrast uptake. These findings are compatible with acute/subacute WE. The patient acknowledged regularly consuming large amounts of alcohol and a diet including no fruits or vegetables. A blood analysis revealed hypertransaminasaemia (GOT 454U/L [normal range, 4-32U/L]; GPT 315U/L [5-33]) and low prealbumin levels at 12mg/dL (normal range, 17-34mg/dL), indicating malnutrition; we decided to intensify treatment with intravenous thiamine dosed at 500mg every 8h.

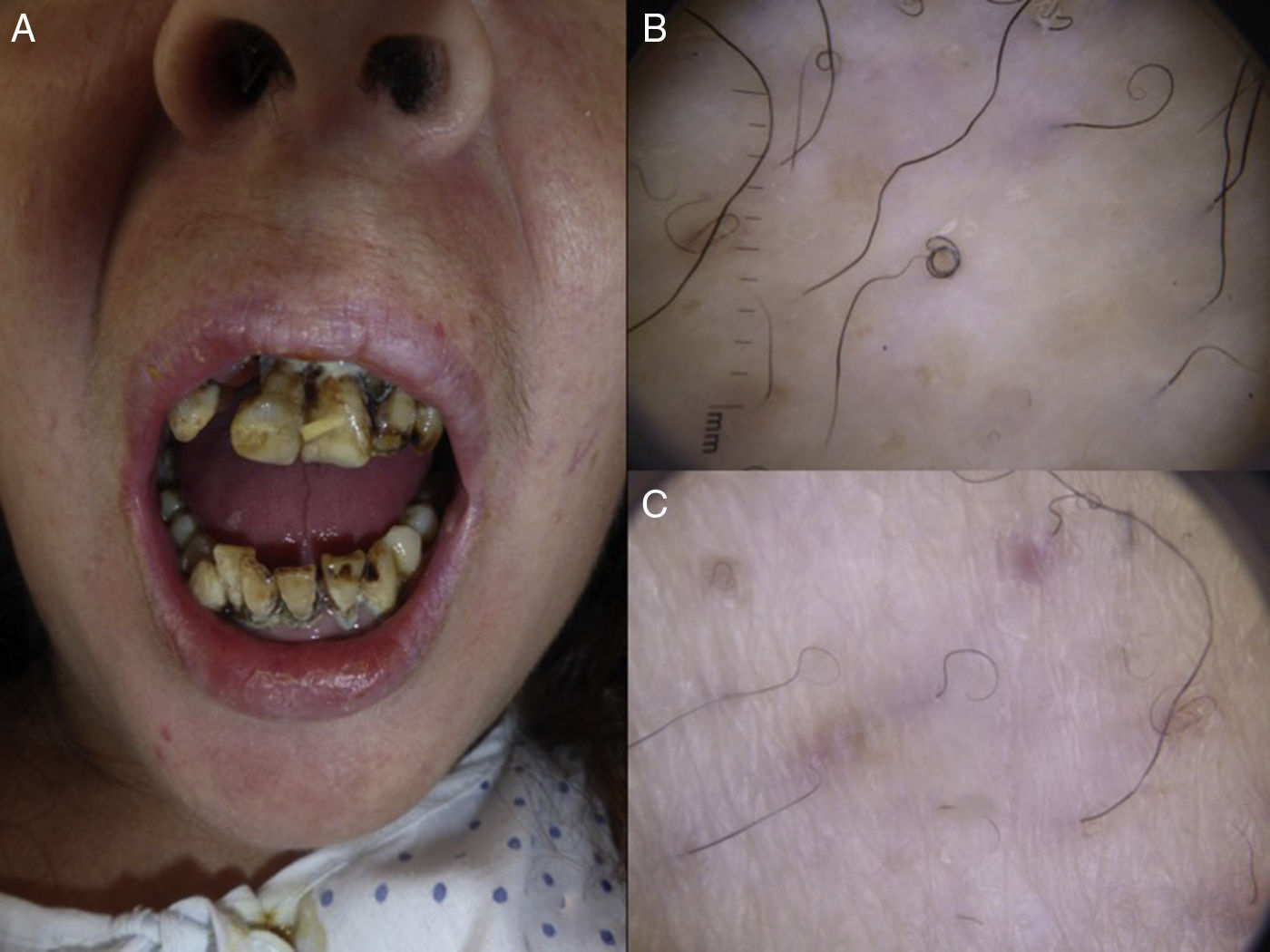

During hospitalisation, the patient was assessed by the dermatology department due to corkscrew hairs and perifollicular purpura on the pretibial area in both legs. The oral cavity showed generalised gingivitis, with the patient reporting frequent bleeding. Two skin biopsies revealed that the infundibula were dilated and filled with keratin plugs surrounded by fibrosis and chronic inflammation. Although we could not determine the plasma ascorbic acid level, we diagnosed scurvy based on the patient's clinical symptoms and started intravenous treatment with 1g vitamin C every 24h for 7 days, followed by oral vitamin C dosed at 200mg/day.

One month after treatment onset, the skin lesions had disappeared and gingival bleeding had stopped; the patient was eating a varied diet and abstaining from drinking alcohol.

At the 3-month follow-up consultation with the neurology department, ataxia had improved but anterograde amnesia persisted.

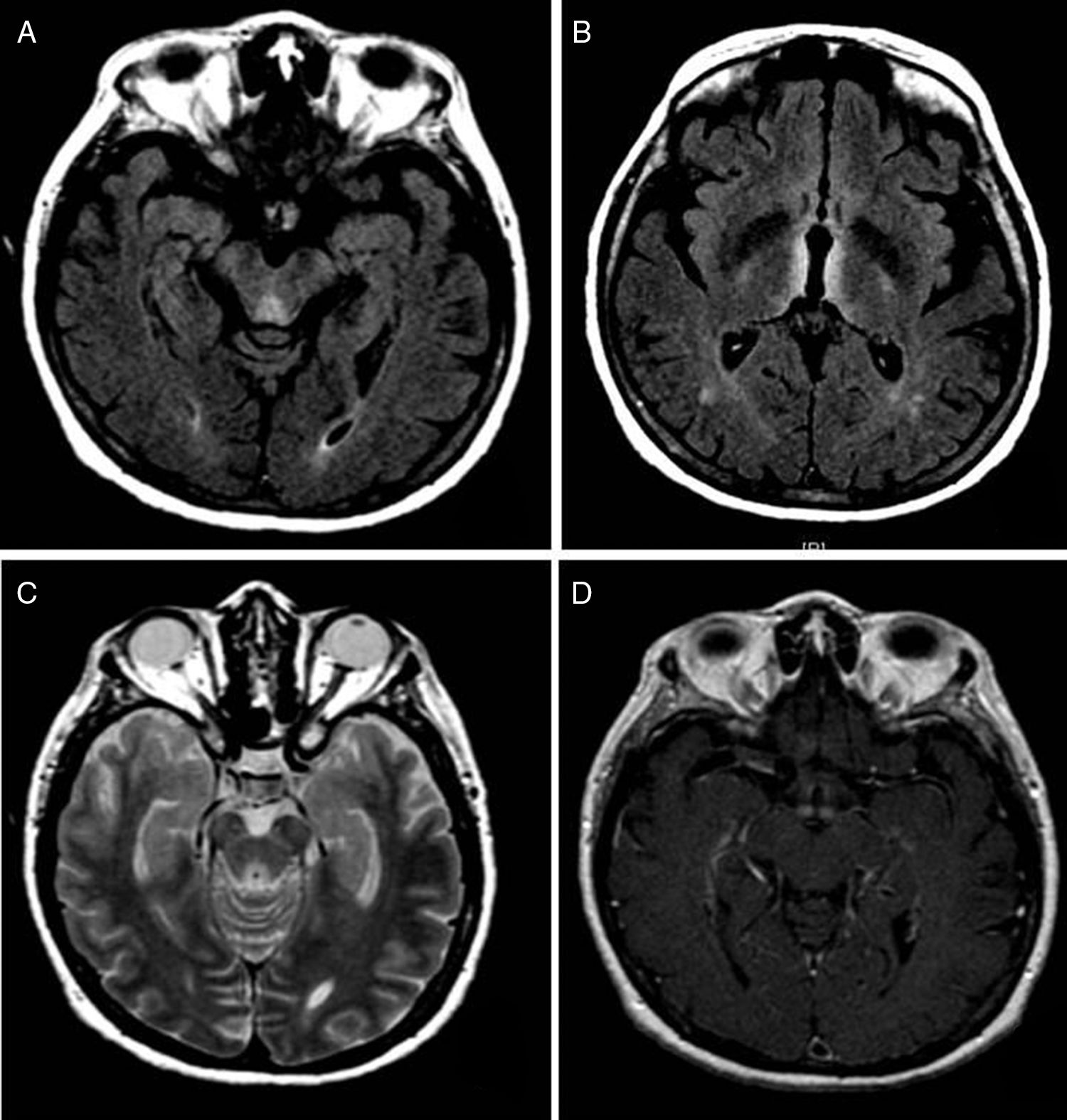

We present the case of a patient with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome with brain MRI findings typical of the acute/subacute phase. The patient also presented scurvy in the context of a multiple deficiency syndrome, which was diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and the improvements observed after vitamin C supplementation (although plasma vitamin C levels could not be determined). These 2 entities are diagnosed clinically and may be cured with appropriate vitamin supplementation. WE is a frequent and probably underdiagnosed disease requiring a high level of clinical suspicion. Imaging studies usually reveal alterations that are rarely observed in other diseases, such as hyperintensities in the medial area of the thalamus bilaterally, in the mamillary bodies, the tectum, and the periaqueductal grey matter on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences. Other atypical locations include the cranial nerve nuclei, cerebellar vermis, red nucleus, dentate nuclei, splenium, and cerebral cortex; these areas are more commonly involved in the non-alcoholic form of the disease. Imaging studies usually detect contrast uptake in the mammillary bodies; uptake is less frequent in other locations (Fig. 1).3–6

(A) Axial FLAIR sequence showing a hyperintense area in the tectum. (B) Axial FLAIR sequence showing bilateral, symmetrical hyperintensities in the thalamus and fornix. (C) Axial T2-weighted sequence revealing a periaqueductal hyperintense lesion. (D) T1-weighted sequence revealing contrast uptake in the mammillary bodies.

Scurvy is caused by ascorbic acid deficiency. Asthenia is the most common systemic symptom; normocytic normochromic anaemia is frequently detected in these patients. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations include gingivitis, follicular hyperkeratosis, follicular purpura, ecchymosis, xeroderma, and corkscrew hairs (Fig. 2).7 Diagnosis is essentially clinical and does not usually require complementary testing; scurvy is easily treated.8 Prevalence is relatively high in patients with nutritional deficiencies; the condition is probably underdiagnosed.9 To our knowledge, the association between scurvy and WE has only been described on 2 occasions. Plasma vitamin C levels were determined in both cases, although the patients received different doses of vitamin C (500mg/day vs 2g/day). One of the patients received the same dose of intravenous thiamine as our patient (500mg/8h); data on the exact dose administered to the other patient are not reported.10,11

The association between WE and scurvy is rare and may be under-reported. A high level of suspicion is therefore needed, since diagnosis is mainly clinical and the 2 entities are potentially curable with early, appropriate vitamin supplementation.

Please cite this article as: Villacieros-Álvarez J, Chicharro P, Trillo S, Barbosa A. Encefalopatía de Wernicke-escorbuto, ¿una asociación infradiagnosticada? Neurología. 2020;35:47–49.