Our hospital is working on a plan to improve the quality of its Emergency Service through the setting up protocols for paediatric pathologies1–6 to unify performance criteria and optimise teaching and clinical practice. The protocols follow methodology and format standards established by the Commission on Technology and Adequacy of Resources and are periodically updated and evaluated to ensure their correct application. This study reviews epidemiological data and compliance with the indicators of the protocol for acute ataxia in the Emergency Service.

Acute ataxia is a rare complaint in the paediatric Emergency Service. Its most frequent origin is usually a trivial pathology caused by drugs, infections or toxic substances, but it can occasionally be a sign of a serious pathology that should be ruled by an accurate medical history, physical examination and complementary tests. For this reason, in accordance with the literature reviewed,7,8 our protocol established the performance of emergency neuroimaging studies (CT, MRI if available), as well as admission for patients presenting papilloedema or other data pointing to intracranial hypertension, clear neurological focality, impaired level of consciousness or no clear aetiological diagnosis after the first few hours. The performance of an MRI was recommended in cases not resolved after this initial investigation.

The protocol for acute ataxia was developed jointly by paediatric neurologists and specialists in paediatric emergencies in October 2004 and was subsequently reviewed in December 2006 to include quality criteria and indicators. It was then updated again after a literature review in January 2009, also proposing a response algorithm.

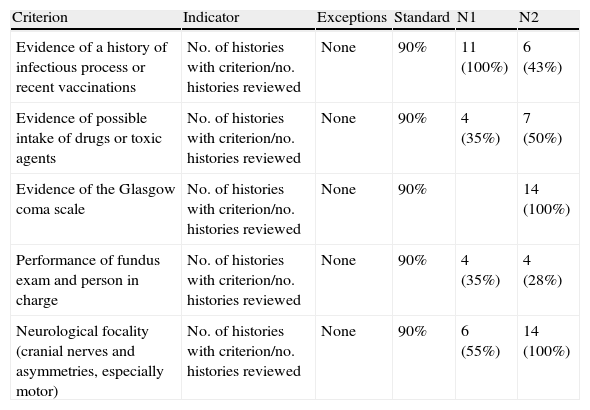

Quality criteria have been established to evaluate the performance and usefulness of the protocol and propose improvement actions (Table 1), comparing them with the previous assessment carried out in 2006.

Quality indicators and compliance rate.

| Criterion | Indicator | Exceptions | Standard | N1 | N2 |

| Evidence of a history of infectious process or recent vaccinations | No. of histories with criterion/no. histories reviewed | None | 90% | 11 (100%) | 6 (43%) |

| Evidence of possible intake of drugs or toxic agents | No. of histories with criterion/no. histories reviewed | None | 90% | 4 (35%) | 7 (50%) |

| Evidence of the Glasgow coma scale | No. of histories with criterion/no. histories reviewed | None | 90% | 14 (100%) | |

| Performance of fundus exam and person in charge | No. of histories with criterion/no. histories reviewed | None | 90% | 4 (35%) | 4 (28%) |

| Neurological focality (cranial nerves and asymmetries, especially motor) | No. of histories with criterion/no. histories reviewed | None | 90% | 6 (55%) | 14 (100%) |

Total cases: N1 (review of cases diagnosed between January 2005 and January 2007) 11; N2 (review of cases diagnosed between January 2007 and January 2009) 14.

The present data were obtained by reviewing the reports of patients registered in the Emergency Service observation unit due to consultation or diagnosis of ataxia or instability, as well as those with discharge diagnoses including acute ataxia, abnormal gait, post-varicella ataxia9 and locomotor ataxia (ICD 9: 781.3, 781.2, 052.7 and 094.0, respectively) between January 2007 and January 2009.

We reviewed the age of presentation, time of evolution until arrival at the Emergency Service, presence of associated symptoms, complementary tests performed, need for hospital or intensive care unit admission, final diagnosis, subsequent control in paediatric neurology consultation and compliance with quality indicators.

A total of 451,413 children were attended by the paediatrics Emergency Service between January 2007 and January 2009. Among these there were 14 cases of acute ataxia, of which 6 were males and 8 were females.

The mean age of presentation was 5.3 years, with 8 (57%) patients being younger than 3. Most patients attended the Emergency Service in the first 24h after the start of symptoms. Two cases presenting a longer evolution, approximately 72h until emergency care, were an acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and a posterior fossa tumour. Of the 14 patients, 7 suffered isolated ataxia, 2 presented associated neurological focality and the remaining 5, vegetative manifestations.

An urgent CT scan was performed in 10 patients, with 8 being normal (whose final diagnoses were 2 intoxications, by ingestion of air freshener and benzodiazepines, respectively, 1 traumatic brain injury, 1 conversion syndrome and 3 cases of ataxia whose origin could not be established). The 2 cases, which presented an altered CT, were the posterior fossa tumour and a case of triventricular hydrocephalus, probably due to aqueductal stenosis, which showed signs of ataxia associated with intracranial hypertension. In both cases, the study was complemented with MRI, which was also performed and was diagnostic in the ADEM case.

The 4 cases in which no neuroimaging tests were carried out were 1 post-varicella ataxia, 1 intoxication, 1 presyncopal case and 1 episode of vertigo.

All patients were admitted, except for 2. One was a case of intoxication presenting transient symptoms, discharged from the Emergency Service observation unit once it remitted; the other was an episode of vertigo. Neither was admitted to the intensive care unit. The cases of ataxia secondary to ADEM, TBI, air freshener intake and those that could not be assigned a cause during admission were monitored in paediatric neurology consultation after discharge.

The results of the fulfilment of quality criteria in the first and second periods are shown in Table 1. After the first review, we emphasised the importance of making written reports of the quality criteria, especially cases of drug or toxic agent intake, the performance of a fundus or the presence of neurological focality, all of which presented a low rate of compliance. Evidence of using the Glasgow coma scale was also introduced as a quality criterion.

In the second self-assessment, we observed a low level of compliance in the evidence of fundus exam completion and relevant anamnesis data, such as intake of drugs or toxic agents, or history of infection or vaccination. However, we believe that this information was gathered in our routine practice but not reflected in writing. In any case, the update of the protocol was presented during a clinical session at our hospital, paying particular attention to the criteria with less compliance or recording.

After comparing both groups, we highlighted the improvement in the recording within clinical histories of the presence or absence of neurological focality. Although the evidence of using the Glasgow coma scale was a new criterion, its compliance was analysed retrospectively and was of 100% in both cases.

The use of protocols and their self-assessment are a means to reduce variability and optimise health care practice. They represent a first-order method in medical training10,11; the evidence suggests that audit and feedback based on these indicators can be effective in changing professional practice.12,13 In our case, this is handled by presenting the results during a clinical session with subsequent proposals for improvement. This evaluation and continuous monitoring process requires a periodic update of bibliography, as well as a review of the latest existing evidence. Protocolization is an important aspect of quality and its evaluation has led us into an open-ended cycle of learning and improvement.