To update the Spanish Society of Neurology’s guidelines for stroke prevention in patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, analysing the available evidence on the effect of metabolic control and the potential benefit of antidiabetic drugs with known vascular benefits in addition to conventional antidiabetic treatments in stroke prevention.

MethodsPICO-type questions (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) were developed to identify practical issues in the management of stroke patients and to establish specific recommendations for each of them. Subsequently, we conducted systematic reviews of the PubMed database and selected those randomised clinical trials evaluating stroke as an independent variable (primary or secondary). Finally, for each of the PICO questions we developed a meta-analysis to support the final recommendations.

ConclusionsWhile there is no evidence that metabolic control reduces the risk of stroke, some families of antidiabetic drugs with vascular benefits have been shown to reduce these effects when added to conventional treatments, both in the field of primary prevention in patients presenting type 2 diabetes and high vascular risk or established atherosclerosis (GLP-1 agonists) and in secondary stroke prevention in patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes (pioglitazone).

Actualizar las recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Neurología para la prevención del ictus en pacientes con DM-2 o prediabetes, analizando las evidencias disponibles sobre el efecto del control metabólico y posible beneficio de los antidiabéticos con beneficio vascular añadidos al tratamiento antidiabético estándar en la prevención de ictus.

DesarrolloSe han elaborado preguntas tipo PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) para identificar cuestiones prácticas para el manejo de pacientes con ictus y poder realizar recomendaciones específicas en cada una de ellas. Posteriormente se han realizado revisiones sistemáticas en Pubmed y se han seleccionado los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados que han evaluado ictus como variable independiente (principal o secundaria). Finalmente se ha elaborado metaanálisis para cada una de las preguntas PICO y se han redactado unas recomendaciones en respuesta a cada una de ellas.

ConclusionesAunque no hay evidencia de que un mejor control metabólico reduzca el riesgo de ictus, algunas familias de antidiabéticos con beneficio vascular han mostrado reducción en el riesgo de ictus cuando se añaden al tratamiento convencional, tanto en el ámbito de prevención primaria en pacientes con DM-2 de alto riesgo vascular o con enfermedad vascular aterosclerosa establecida (agonistas GLP-1) como en prevención secundaria de ictus en pacientes con DM-2 y prediabetes (pioglitazona).

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) and prediabetes increase the risk of vascular diseases in the context of hyperglycaemia and poor metabolic control.1–6 Around 60%-70% of patients with stroke present history of DM2 or prediabetes,7,8 which, in turn, are associated with increased risk of recurrence.9–12 In patients with DM2, vascular prevention strategies focus on introducing lifestyle changes (healthy diet, regular physical activity, and smoking cessation), managing the associated vascular risk factors (particularly dyslipidaemia and arterial hypertension), and promoting the use of antiplatelet drugs.13,14

Several clinical trials conducted in recent decades have concluded that tight glycaemic control (HbA1c < 6%-6.5%, as compared to HbA1c < 7%-8%) is associated with a decrease in the risk of microvascular damage and a small decrease in the risk of non-fatal coronary events, particularly myocardial infarction, although it does not decrease the risk of death or stroke but does increase the risk of symptomatic hypoglycaemia.14–18 These observations have had a considerable impact on the recommendations issued by different diabetes associations; for most patients with DM2, HbA1c < 7% is considered a reasonable target for reducing the risk of microvascular events.14,19

Furthermore, since the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established the need to assess the vascular safety of antidiabetic drugs, significant advances have been made in our understanding of the vascular benefits of some of these agents, such as sodium-glucose linked transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, which have been shown to reduce the risk of the composite endpoint of vascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in patients with established atherosclerotic vascular disease or high vascular risk.20 This evidence has led the American Diabetes Association to recommend adding a GLP-1 receptor agonist or an SGLT2 inhibitor to the first-line treatment (metformin) in patients with established vascular disease or high vascular risk.14 The Spanish Diabetes Society also recommends adding thiazolidinediones,19 since pioglitazone has also shown vascular benefits.

In the light of these advances, the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Stroke Study Group has decided to update its guidelines on stroke prevention and treatment,21 including a chapter on stroke prevention in patients with DM2 or prediabetes. The first part of this consensus document focuses on the effects of metabolic control (decrease in HbA1c levels), whereas the second part analyses the potential benefits of adding pioglitazone, SGLT2 inhibitors, or GLP-1 receptor agonists to standard antidiabetic treatment in patients with stroke and DM2 or prediabetes. The document does not analyse the effects of other antidiabetic drugs including dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, which have failed to show overall vascular benefits or a decrease in the risk of stroke in the clinical trials conducted to date.20

MethodsWe initially formulated patient, intervention, comparison, and outcome questions (PICO strategy) to identify practical issues in the management of patients with stroke that may enable us to issue specific recommendations. To evaluate the effects of tight glycaemic control on the risk of stroke, we performed a systematic literature search on PubMed (conducted between 18 August 2019 and 1 October 2019) using the following search strategy: (((intensive blood glucose control) OR glycated hemoglobin) AND randomized trial) AND stroke AND diabetes; ((((Tiazolidinediones) OR glitazones) OR pioglitazone) AND trial) AND stroke AND diabetes; (((((((Sglt2 Inhibitor) OR Empagliflozin) OR Canagliflozin) OR Dapagliflozin) AND Diabetes) AND Trial) AND Stroke) AND Diabetes; ((((((((GLP-1 Agonist) OR dulaglutide) OR albiglutide) OR semaglutide) OR liraglutide) OR exenatide) OR lixisenatide) AND trial) AND stroke AND diabetes; ((((Prediabetes) OR Insulin Resistance) AND Antidiabetic Drug) AND Stroke) AND Trial.

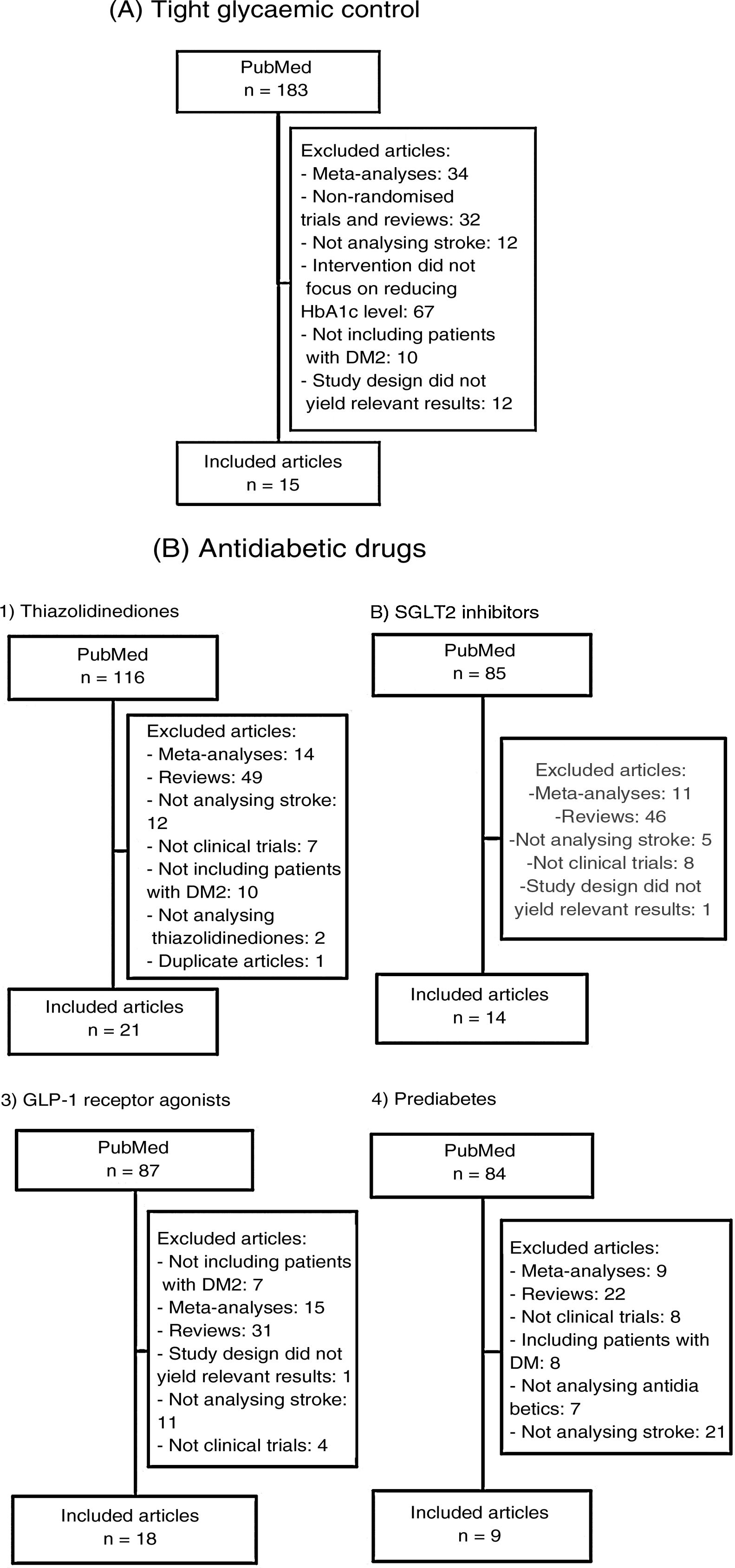

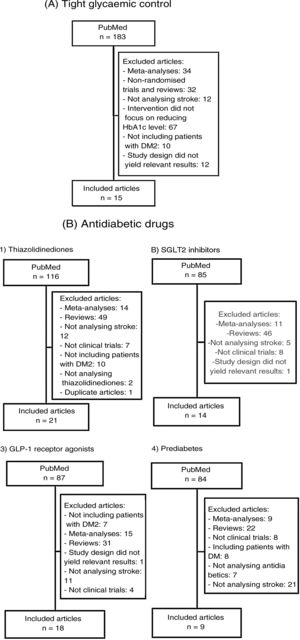

We subsequently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the articles identified in the literature search and selected those meeting the following criteria: 1) reporting a randomised clinical trial, and 2) including stroke as an independent variable (primary or secondary). We excluded meta-analyses, non-systematic literature reviews, clinical trials including populations other than patients with DM2 or prediabetes, and clinical trials not including stroke as an outcome variable. Fig. 1A and B summarise the article selection process; meta-analyses were performed using version 5.3.5 of the Review Manager 5 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014; Copenhagen, Denmark). The data included in the meta-analyses were preferentially drawn from the primary publication for each clinical trial; in some cases, supplementary material or secondary publications were also consulted. Based on the results of our meta-analyses, we drafted a series of recommendations addressing each of the questions proposed, considering the strength of recommendation as follows: class I (strong; benefit clearly outweighs the risk), class IIa (moderate; benefit outweighs the risk), class IIb (weak), and class III (no benefit; benefit is equal to the risk).22 To analyse the safety profile of each drug, we gathered data on the main severe adverse reactions of each antidiabetic drug family reported in the clinical trials; when these data were not provided in the primary publication or its supplementary material, we consulted the published meta-analyses. Evidence was classified as level A (high-quality evidence from more than one randomised trial, meta-analyses of high-quality clinical trials, or randomised clinical trial data corroborated by high-quality registry studies), level B (moderate-quality evidence, based on one or more randomised clinical trials; one or more non-randomised, observational, or high-quality registry studies; meta-analyses of moderate-quality clinical trials; or meta-analyses of non-randomised studies), or level C (limited evidence, with data from observational studies or registry studies presenting methodological limitations in design or execution).22 We made additional comments to contextualise the recommendations. Tables 1 and 2 summarise the main characteristics of the clinical trials included in the study.

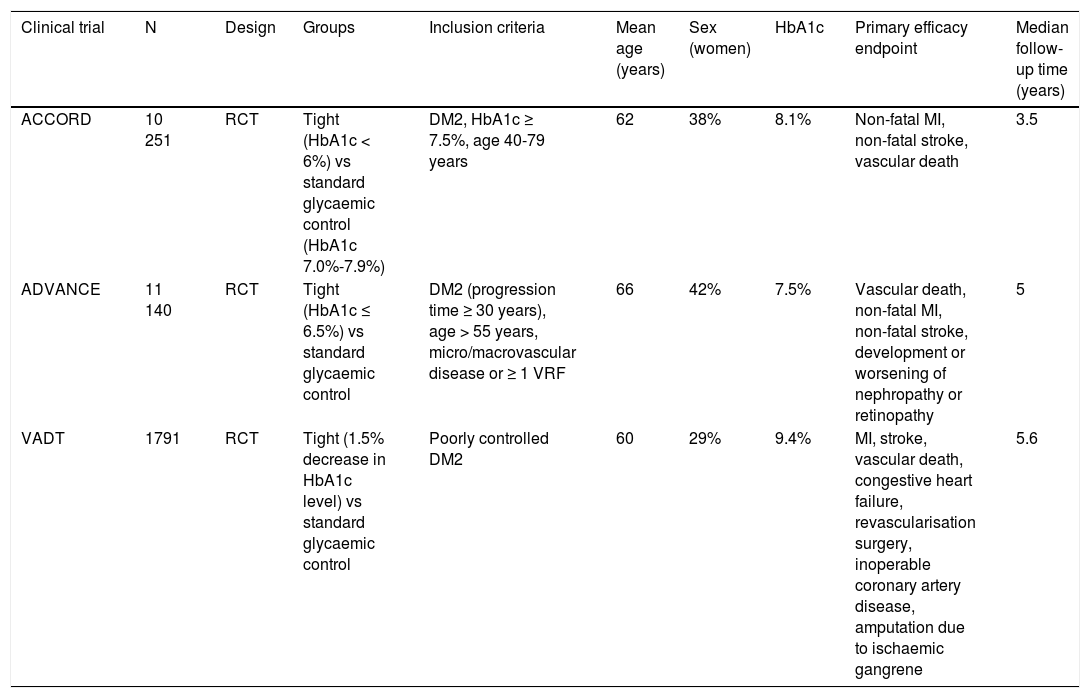

Main characteristics of the clinical trials evaluating the benefits of tight glycaemic control (target HbA1c level).

| Clinical trial | N | Design | Groups | Inclusion criteria | Mean age (years) | Sex (women) | HbA1c | Primary efficacy endpoint | Median follow-up time (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACCORD | 10 251 | RCT | Tight (HbA1c < 6%) vs standard glycaemic control (HbA1c 7.0%-7.9%) | DM2, HbA1c ≥ 7.5%, age 40-79 years | 62 | 38% | 8.1% | Non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, vascular death | 3.5 |

| ADVANCE | 11 140 | RCT | Tight (HbA1c ≤ 6.5%) vs standard glycaemic control | DM2 (progression time ≥ 30 years), age > 55 years, micro/macrovascular disease or ≥ 1 VRF | 66 | 42% | 7.5% | Vascular death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, development or worsening of nephropathy or retinopathy | 5 |

| VADT | 1791 | RCT | Tight (1.5% decrease in HbA1c level) vs standard glycaemic control | Poorly controlled DM2 | 60 | 29% | 9.4% | MI, stroke, vascular death, congestive heart failure, revascularisation surgery, inoperable coronary artery disease, amputation due to ischaemic gangrene | 5.6 |

DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; MI: myocardial infarction; RCT: randomised clinical trial; VRF: vascular risk factor.

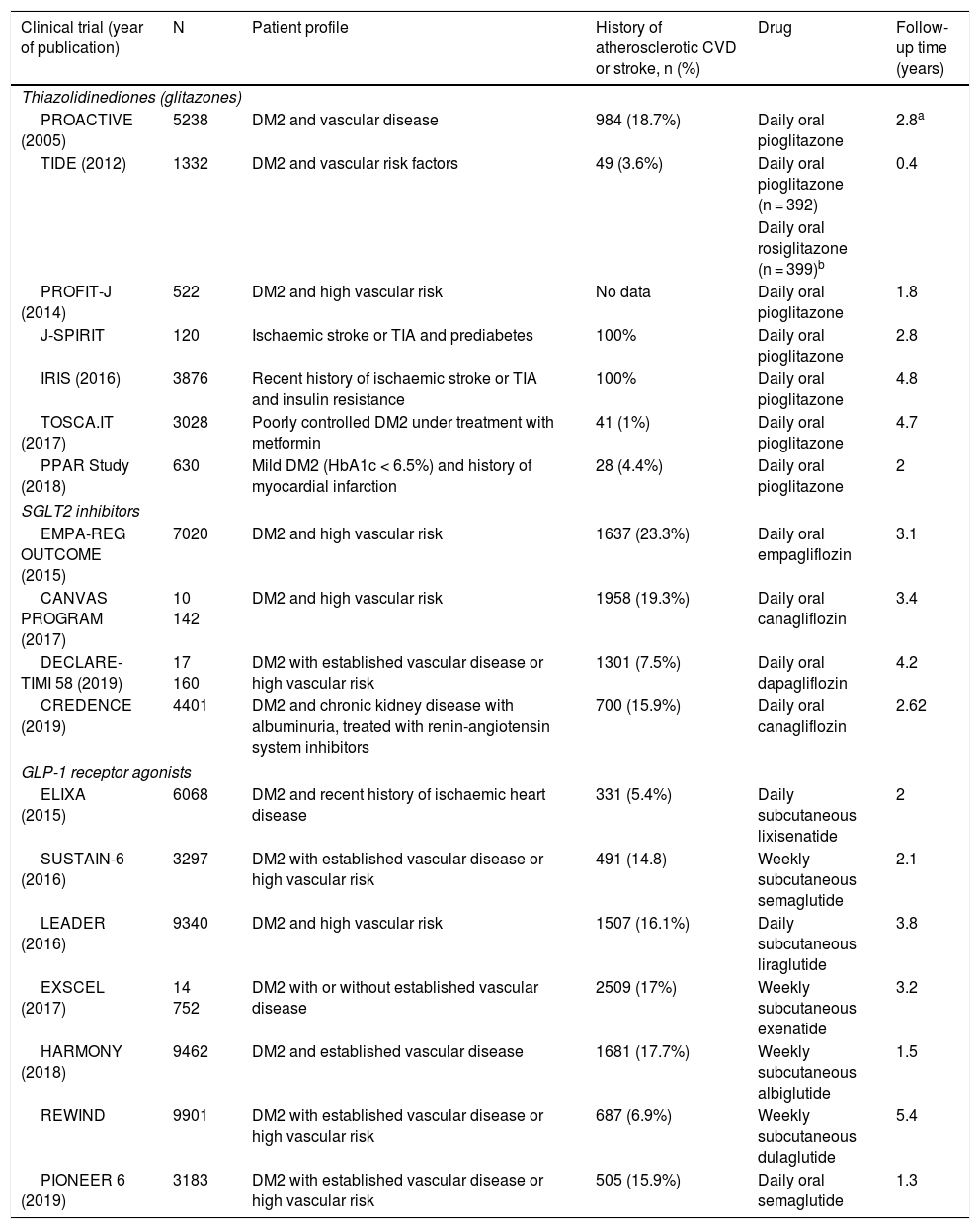

Main characteristics of the included clinical trials evaluating the benefits of antidiabetic drugs for stroke prevention.

| Clinical trial (year of publication) | N | Patient profile | History of atherosclerotic CVD or stroke, n (%) | Drug | Follow-up time (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiazolidinediones (glitazones) | |||||

| PROACTIVE (2005) | 5238 | DM2 and vascular disease | 984 (18.7%) | Daily oral pioglitazone | 2.8a |

| TIDE (2012) | 1332 | DM2 and vascular risk factors | 49 (3.6%) | Daily oral pioglitazone (n = 392) | 0.4 |

| Daily oral rosiglitazone (n = 399)b | |||||

| PROFIT-J (2014) | 522 | DM2 and high vascular risk | No data | Daily oral pioglitazone | 1.8 |

| J-SPIRIT | 120 | Ischaemic stroke or TIA and prediabetes | 100% | Daily oral pioglitazone | 2.8 |

| IRIS (2016) | 3876 | Recent history of ischaemic stroke or TIA and insulin resistance | 100% | Daily oral pioglitazone | 4.8 |

| TOSCA.IT (2017) | 3028 | Poorly controlled DM2 under treatment with metformin | 41 (1%) | Daily oral pioglitazone | 4.7 |

| PPAR Study (2018) | 630 | Mild DM2 (HbA1c < 6.5%) and history of myocardial infarction | 28 (4.4%) | Daily oral pioglitazone | 2 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | |||||

| EMPA-REG OUTCOME (2015) | 7020 | DM2 and high vascular risk | 1637 (23.3%) | Daily oral empagliflozin | 3.1 |

| CANVAS PROGRAM (2017) | 10 142 | DM2 and high vascular risk | 1958 (19.3%) | Daily oral canagliflozin | 3.4 |

| DECLARE-TIMI 58 (2019) | 17 160 | DM2 with established vascular disease or high vascular risk | 1301 (7.5%) | Daily oral dapagliflozin | 4.2 |

| CREDENCE (2019) | 4401 | DM2 and chronic kidney disease with albuminuria, treated with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors | 700 (15.9%) | Daily oral canagliflozin | 2.62 |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | |||||

| ELIXA (2015) | 6068 | DM2 and recent history of ischaemic heart disease | 331 (5.4%) | Daily subcutaneous lixisenatide | 2 |

| SUSTAIN-6 (2016) | 3297 | DM2 with established vascular disease or high vascular risk | 491 (14.8) | Weekly subcutaneous semaglutide | 2.1 |

| LEADER (2016) | 9340 | DM2 and high vascular risk | 1507 (16.1%) | Daily subcutaneous liraglutide | 3.8 |

| EXSCEL (2017) | 14 752 | DM2 with or without established vascular disease | 2509 (17%) | Weekly subcutaneous exenatide | 3.2 |

| HARMONY (2018) | 9462 | DM2 and established vascular disease | 1681 (17.7%) | Weekly subcutaneous albiglutide | 1.5 |

| REWIND | 9901 | DM2 with established vascular disease or high vascular risk | 687 (6.9%) | Weekly subcutaneous dulaglutide | 5.4 |

| PIONEER 6 (2019) | 3183 | DM2 with established vascular disease or high vascular risk | 505 (15.9%) | Daily oral semaglutide | 1.3 |

CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

We identified 3 randomised clinical trials whose main objective was to evaluate the effect of tight glycaemic control on the risk of vascular events as compared to standard treatment. Glycaemic targets (absolute or relative threshold HbA1c values) and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies used differed between trials.

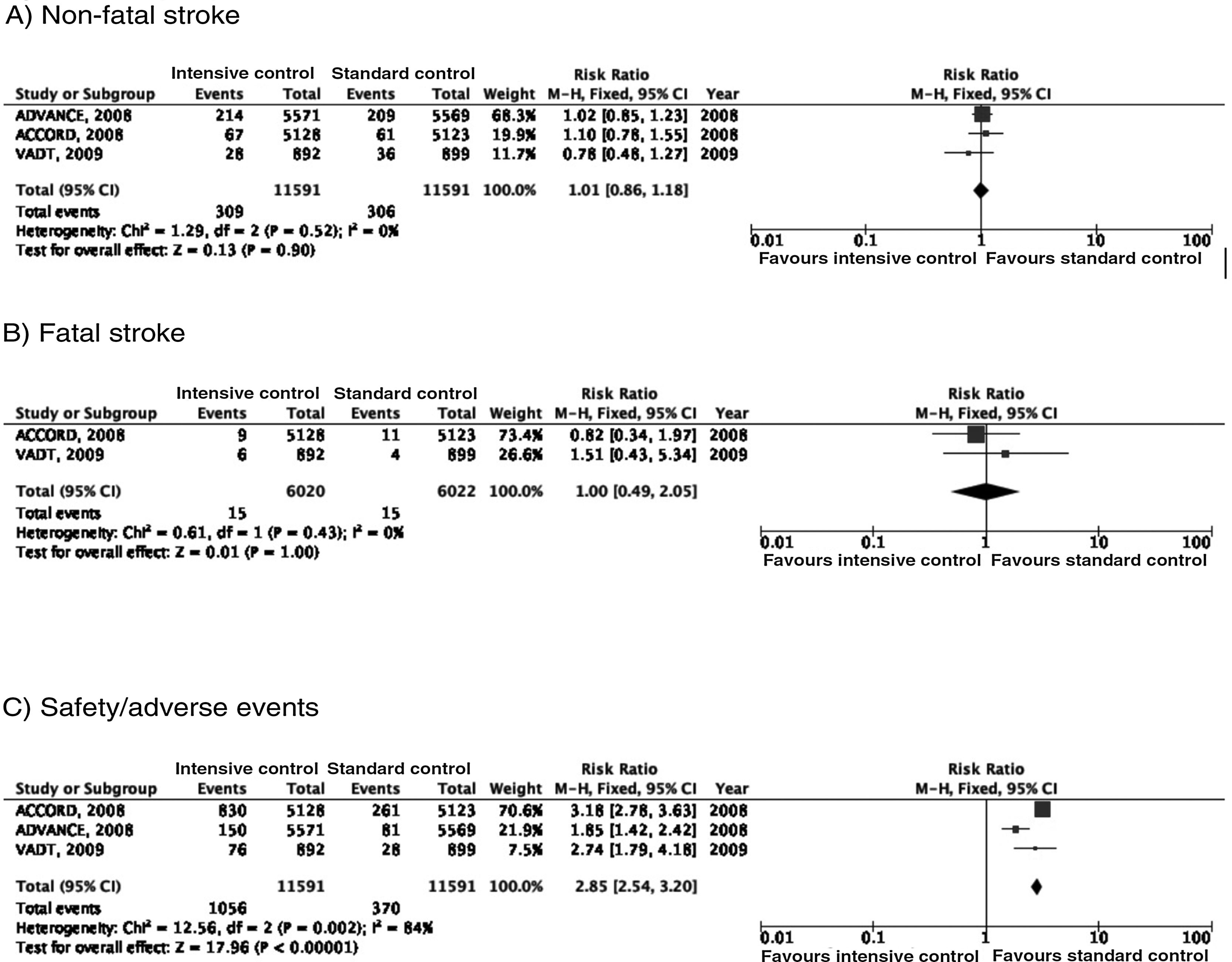

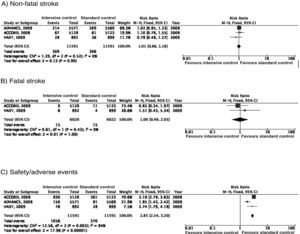

In the ACCORD trial,23–28 tight glycaemic control (target: HbA1c < 6%) was associated with greater mortality as compared to standard glycaemic targets; this led to suspension of the trial after 3.5 years of follow-up. In the intensive glycaemic treatment group, 67 of 5128 patients (1.3%) presented non-fatal stroke during follow-up, as compared to 61 cases among the 5123 patients (1.2%) included in the standard glycaemic treatment group; the incidence of fatal stroke was identical in both groups (0.2%) (Fig. 2). In the trial, the primary outcome of efficacy was defined as presentation of non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and/or vascular death; no differences were observed between groups (HR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.78-1.04; P = .16). Both the mortality rate and the incidence of symptomatic hypoglycaemia were greater in the group receiving intensive glycaemic treatment.

In the ADVANCE trial,17,29–31 214 of the 5571 (3.8%) patients randomised to receive intensive glycaemic treatment (HbA1c target < 6.5%) presented non-fatal stroke during follow-up (median of 5 years), compared to 209 of 5569 patients in the standard glycaemic treatment group (3.8%) (Fig. 2). The primary outcome of efficacy was defined as vascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and/or occurrence or worsening of such microvascular complications as nephropathy and retinopathy. Intensive glycaemic treatment decreased the incidence of macrovascular and microvascular disease in combination (HR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.98; P = .01) and microvascular disease alone (HR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77-0.97; P = .01), especially due to its protective effects against kidney damage (HR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P = ¡.006). However, no differences were observed in the incidence of macrovascular disease alone or in mortality rates. Severe hypoglycaemia was more frequent in the group receiving intensive glycaemic treatment.

The VATD study also found no differences in the incidence of stroke between patients receiving intensive glycaemic treatment (1.5% reduction in HbA1c) and those receiving standard treatment.18,32–34 The primary outcome of efficacy was defined as incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, vascular death, congestive heart failure, revascularisation surgery, peripheral vasculopathy, inoperable coronary artery disease, and/or amputation due to ischaemic gangrene; no significant differences were observed between groups (HR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74-1.05; P = .14). No significant inter-group differences were observed in mortality or incidence of microvascular disease, with the exception of progression of microalbuminuria, which was less marked in the intensive glycaemic treatment group.

RecommendationsTight glycaemic control is not recommended for stroke prevention in patients with DM2 (class III recommendation, level of evidence B).

Additional commentsIn an open-label study including 10 years of follow-up of the patients included in the UKPDS study, no significant differences were observed in the risk of stroke between the group receiving intensive glycaemic treatment (target fasting plasma glucose level < 6 mmol/L, or < 108 mg/dL) and those receiving non-intensive glycaemic treatment (6.3 vs 6.9 cases per 1000 patient-years; relative risk [RR] = 0.91; 95% CI, 0.73-1.13; P = .39).35,36 Furthermore, in the group of patients receiving intensive treatment, no significant differences were identified in the risk of stroke between patients treated and not treated with metformin (6.0 vs 6.8 cases per 1000 patient-years; RR = 0.80; 95% CI, 050-1.27; P = .35). However, the intensive glycaemic treatment group did show a significant decrease in the risk of vascular events associated with DM2, particularly in the incidence of microvascular disease, myocardial infarction, or death due to any cause. Therefore, for most patients with DM2, an HbA1c level < 7% represents a reasonable target for reducing the risk of microvascular events. More or less intensive glycaemic control (HbA1c < 6.5% or > 8%) may be indicated on an individual basis.

PICO 2: In patients with DM2 and history of stroke, does good glycaemic control (HbA1c < 7%) reduce the risk of stroke recurrence as compared to poor glycaemic control (HbA1c > 7%)?Our systematic review did not identify any clinical trials specifically evaluating how the intensity of metabolic control affects patients with stroke; we are therefore unable to issue specific recommendations regarding the secondary prevention of stroke.

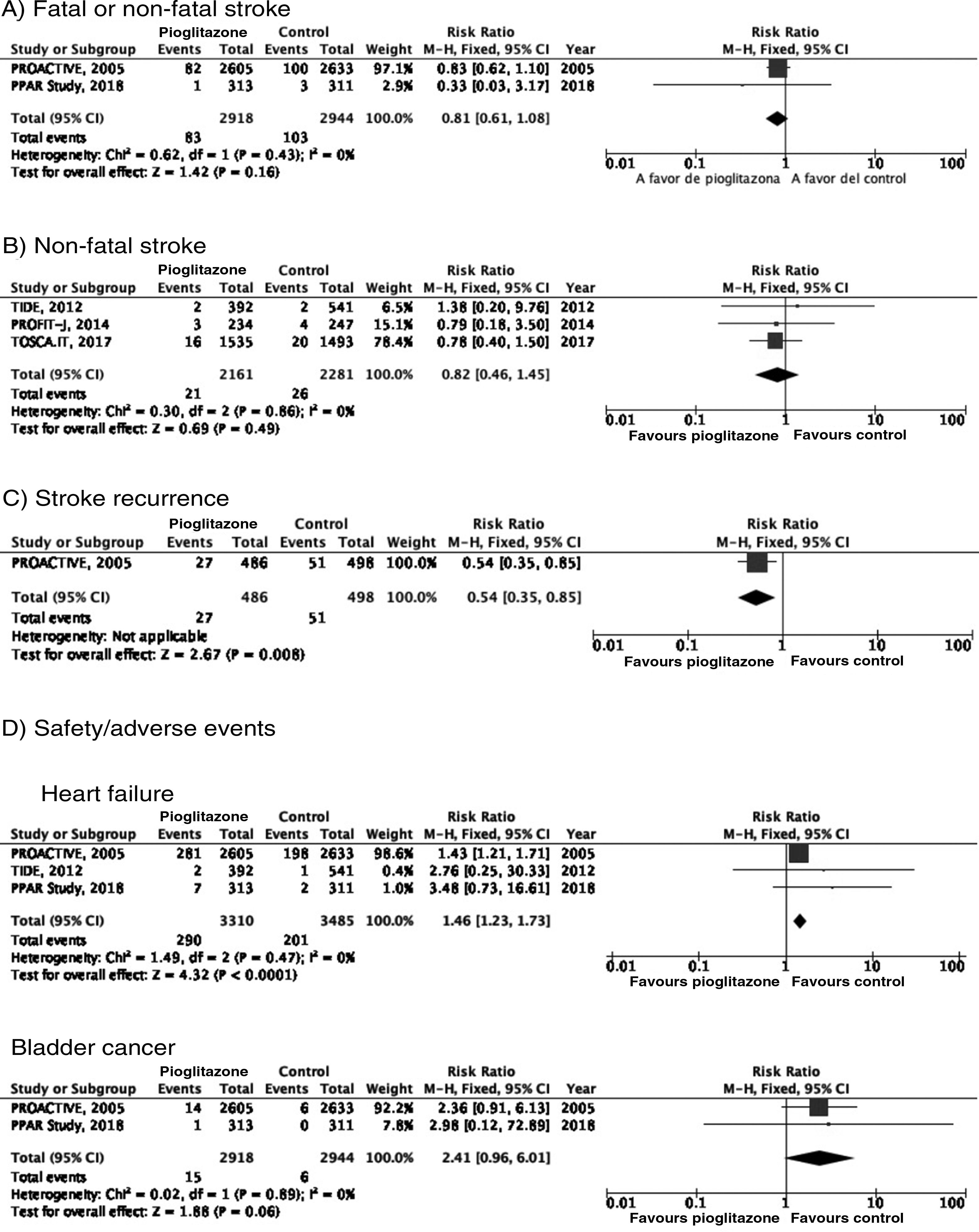

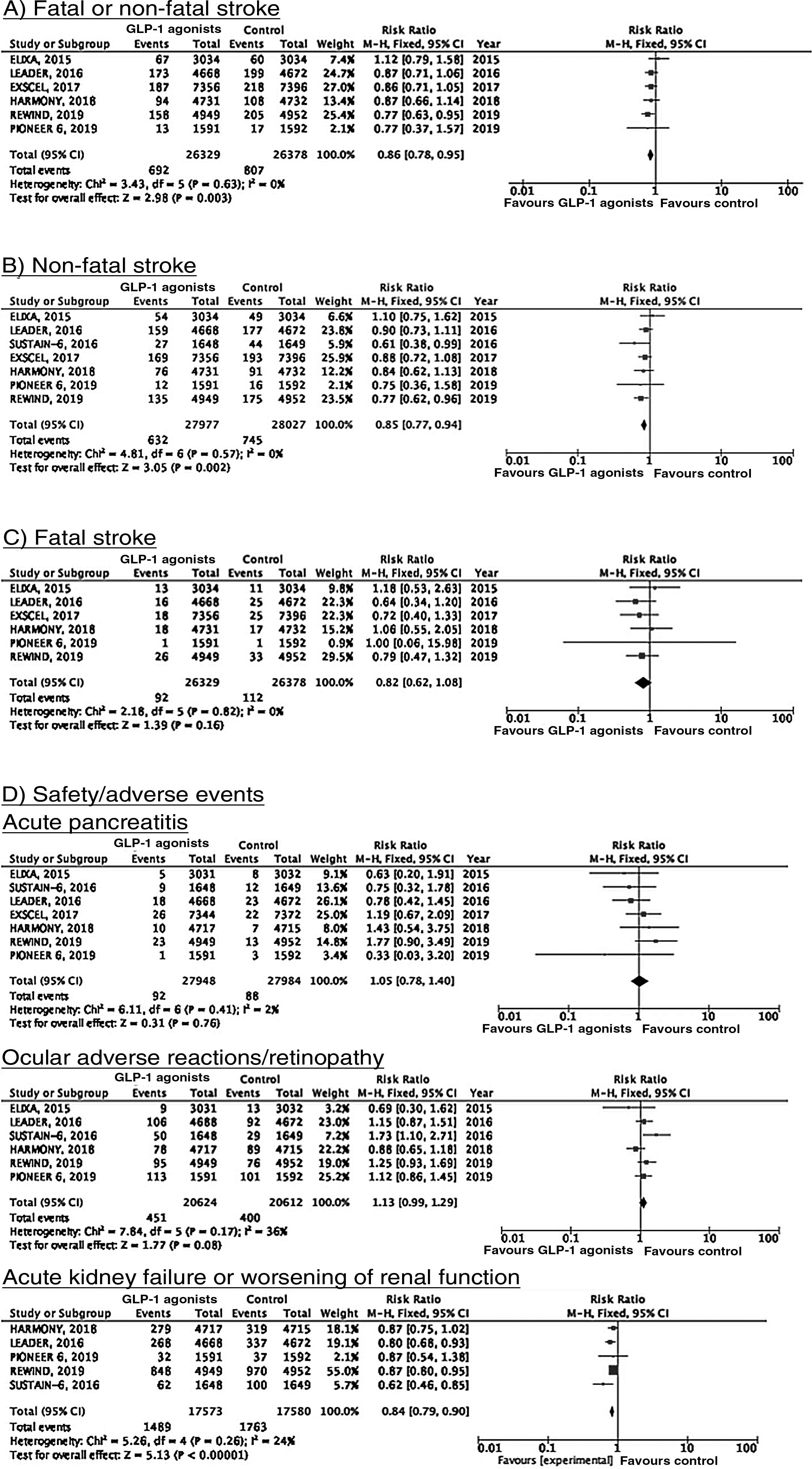

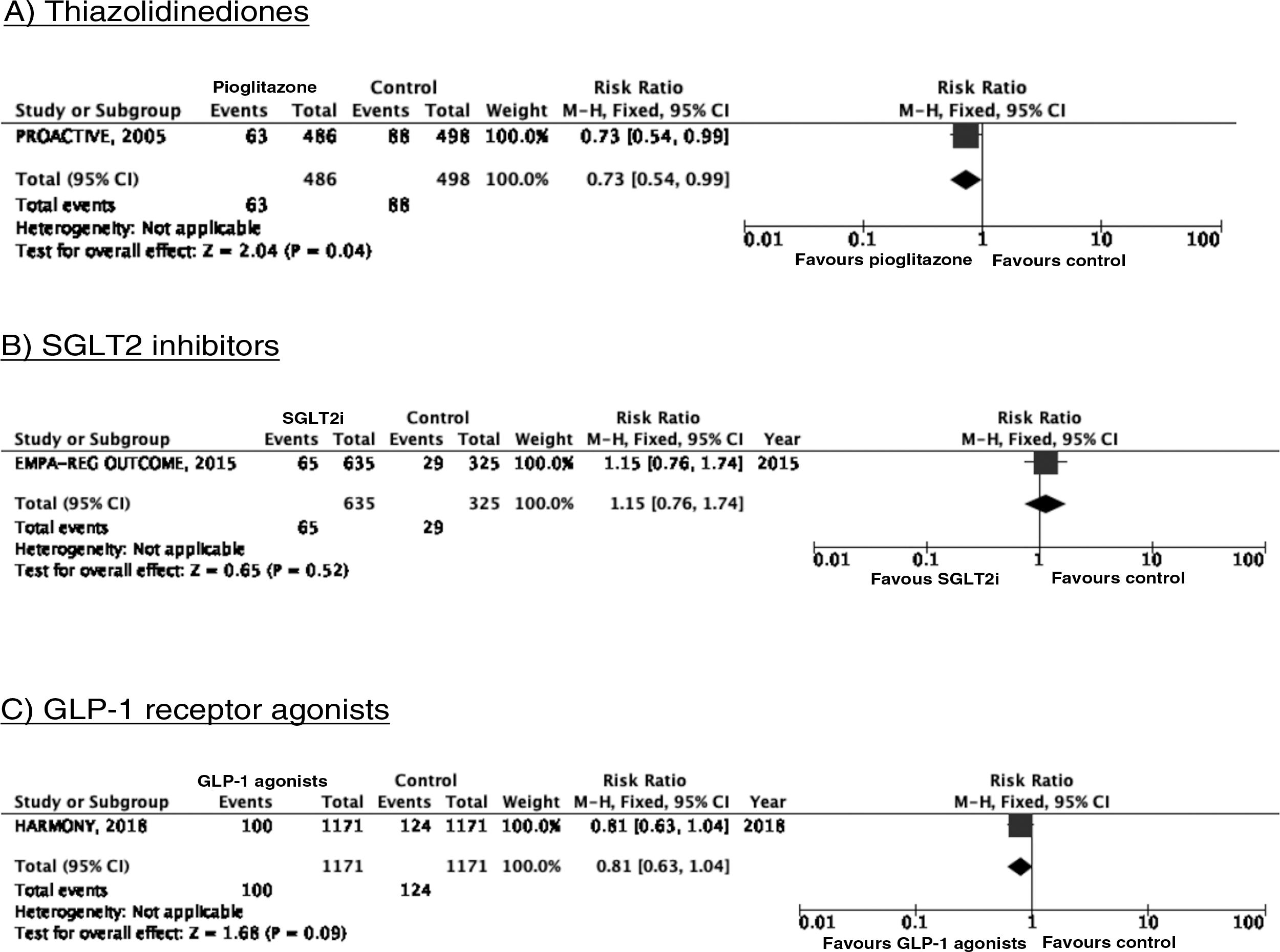

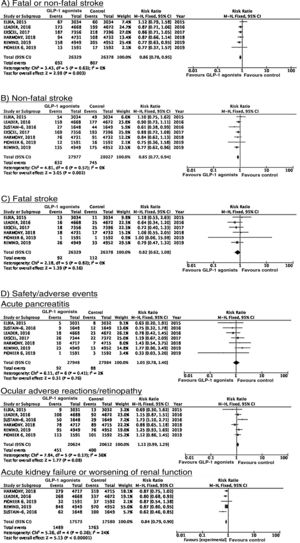

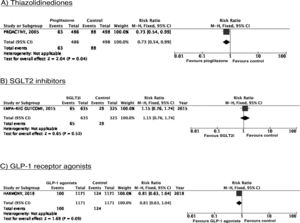

PICO 3: In patients with DM2, does adding antidiabetic drugs with cardiovascular benefits to standard antidiabetic treatment reduce the risk of stroke as compared to administering standard antidiabetic treatment alone?ThiazolidinedionesOf the 7 clinical trials included among the 21 articles identified in our systematic search, 4 evaluated the effects of pioglitazone (PROactive,37–47 PROFIT-J,48 TOSCA.IT,49–51 and PPAR52), 2 evaluated rosiglitazone (RECORD53,54 and BARI 2D55,56), and one (TIDE57) included a control group and 2 active treatment arms (pioglitazone and rosiglitazone), but had to be prematurely terminated at 162 days due to regulatory issues. As rosiglitazone has been withdrawn from the market due to safety concerns, we excluded the RECORD and BARI 2D trials from our meta-analyses, and only gathered data on pioglitazone from the TIDE trial. As shown in Fig. 3, pioglitazone was associated with a non-significant decrease in the RR of stroke (fatal or non-fatal) and non-fatal stroke. The main adverse effect of the drug was heart failure.

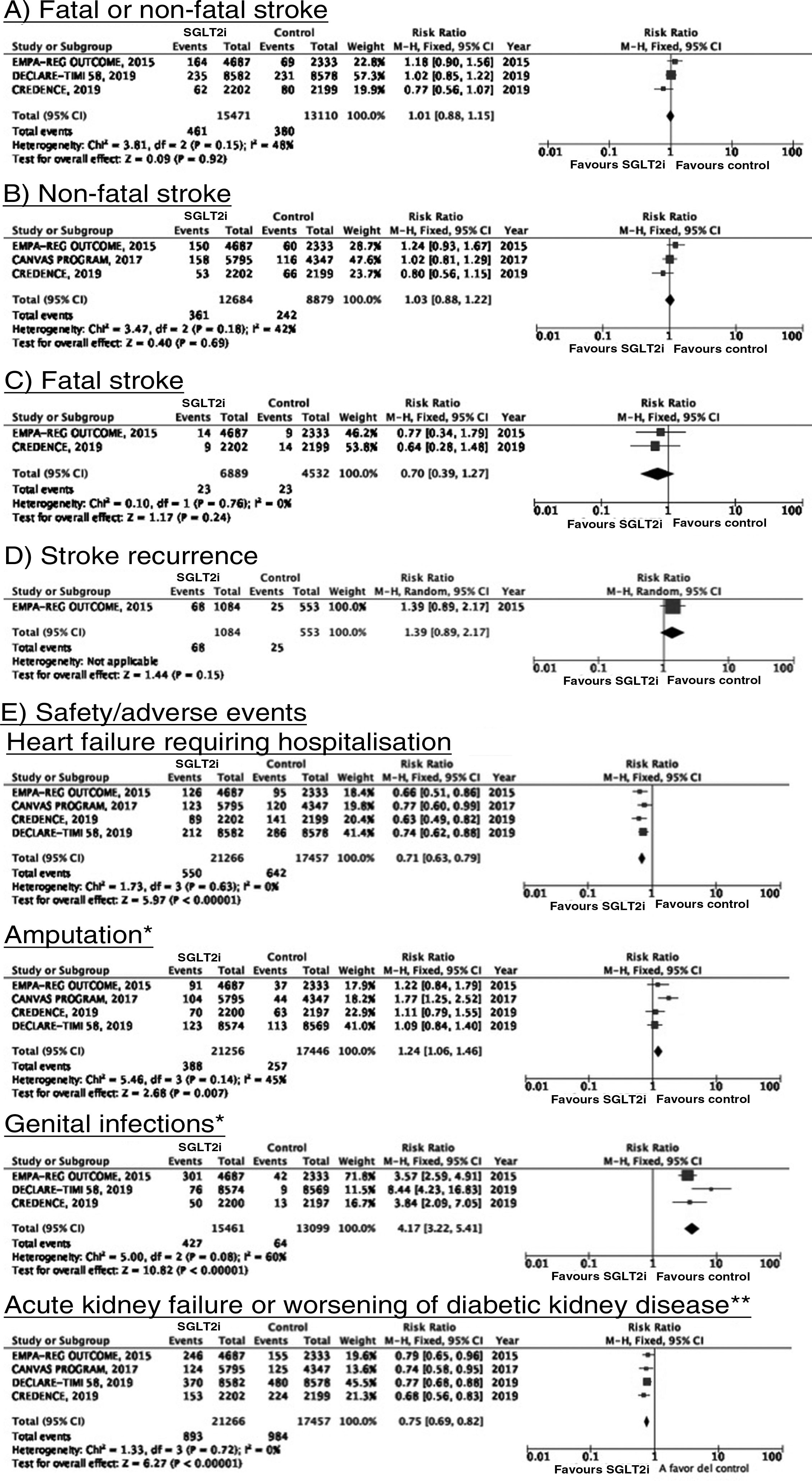

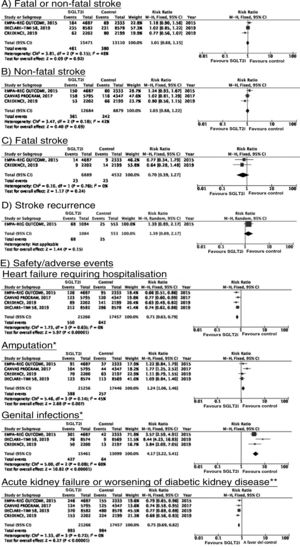

SGLT2 inhibitorsWe identified 4 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of SGLT2 in patients with DM2 and including stroke as a secondary outcome: EMPA-REG OUTCOME (oral empagliflozin),58–62 CANVAS (oral canagliflozin),63–66 CREDENCE (oral canagliflozin),67,68 and DECLARE-TIMI 58 (oral dapagliflozin),69–71 including a total of 38 723 patients, 5596 of whom had history of stroke or atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease (Table 1). The VERTIS-CV trial72 evaluates the safety and efficacy of ertugliflozin. At the time of writing, only the design and baseline patient characteristics have been published; this trial has therefore been excluded from our meta-analysis. Treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors was not associated with a decrease in the RR of fatal stroke, non-fatal stroke, or fatal or non-fatal stroke. The safety analysis revealed significant decreases in the rate of hospitalisations due to heart failure and in the incidence of acute kidney failure or progression of diabetic kidney disease, and an increase in the incidence of amputation associated with use of canagliflozin (CANVAS73) and of genital infections (Fig. 4).

SGLT2 inhibitors for stroke prevention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

*Data on the number of amputations in the CANVAS programme and the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial were gathered from the meta-analysis conducted by Dicembrini et al.73 The analysis of genital infections does not include data from the CANVAS programme since that study expressed data as number of cases per 1000 patient-years; however, this study also reported a significant increase in the incidence of genital infections.

**Diagnostic criteria varied between trials.

To date, 7 randomised clinical trials have assessed the efficacy of GLP-1 receptor agonists for stroke prevention in patients with DM2 and established vascular disease or high vascular risk: ELIXA (daily oral lixisenatide),74–76 SUSTAIN 6 (weekly subcutaneous semaglutide),77,78 LEADER (daily subcutaneous liraglutide),79–82 EXSCEL (weekly subcutaneous exenatide),83–85 HARMONY (weekly subcutaneous albiglutide),86,87 REWIND (weekly subcutaneous dulaglutide),88,89 and PIONEER 6 (daily oral semaglutide)90,91; these trials include a total of 56 004 patients. Of these, 7711 (13.7%) presented history of cerebrovascular disease or stroke (Table 1). Treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists was associated with a 14% decrease in the RR of fatal or non-fatal stroke (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.95) and a 15% decrease in the RR of non-fatal stroke (RR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.94), and no significant difference in the RR of fatal stroke (RR = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.62-1.08). The safety analysis found no significant increases in the risk of pancreatitis or diabetic retinopathy, with the added benefit of a decrease in the risk of acute kidney failure or worsening of kidney function (Fig. 5).

RecommendationsIn patients with DM2 and established vascular disease or high vascular risk, we recommend adding GLP-1 receptor agonists to standard antidiabetic treatment for fatal and non-fatal stroke prevention (class I recommendation, level of evidence B).

In patients with DM2 and established vascular disease or high vascular risk, adding pioglitazone or SGLT2 inhibitors to standard antidiabetic treatment is not recommended for stroke prevention (class III recommendation, level of evidence B).

Additional commentsAlthough a non-significant trend toward a decrease in stroke (fatal or non-fatal) and in non-fatal stroke was observed in the meta-analysis of the 5 clinical trials of plioglitazone, the 6- and 10-year follow-up of the PROactive trial revealed no difference in the long-term risk of stroke.39,47

PICO 4: In patients with DM2 and history of stroke, does adding antidiabetic drugs with cardiovascular benefits to standard antidiabetic treatment reduce the risk of stroke recurrence as compared to administering standard antidiabetic treatment alone?ThiazolidinedionesNo clinical trial has evaluated the effects of thiazolidinediones for the secondary prevention of stroke in patients with DM2. The PROactive trial is the only clinical trial of pioglitazone for which a post-hoc analysis has been published assessing the prevention of stroke recurrence in the subgroup of patients with history of stroke; the analysis identified a 46% decrease in the risk of recurrent stroke (Fig. 3).40

SGLT2 inhibitorsTo date, no clinical trials have studied the use of SGLT2 inhibitors for the secondary prevention of stroke. The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial (Fig. 4) and the CANVAS programme have published data on the risk of stroke in patients with history of cerebrovascular disease.61,64 Neither study found SGLT2 inhibitors to have a significant effect on stroke recurrence. The CANVAS programme expresses data in patient-years and does not provide the number of patients with recurrent stroke per study group; this study was therefore not included in our meta-analysis. In any case, the drug was found to have no significant effect on the risk of recurrent stroke (HR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.61-1.26).64 A post-hoc analysis of the CREDENCE trial, studying the effects of canagliflozin for the primary and secondary prevention of established vascular disease (history of myocardial infarction or stroke) provides no specific data on stroke recurrence in patients with history of stroke.68 The DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial has not yet provided any data on the effects of dapagliflozin on stroke recurrence.

GLP-1 receptor agonistsNo clinical trial has analysed the effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists for secondary stroke prevention; however, post-hoc analyses of the LEADER and SUSTAIN 6 trials evaluated the effects of liraglutide and semaglutide in the subgroup of patients with history of stroke or myocardial infarction78,82 and found no significant decreases in the risk of non-fatal stroke, except for liraglutide in patients with glomerular filtration rates < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.81 The LEADER trial also published a post-hoc analysis of patients with DM2 and polyvascular disease (defined as atherosclerosis involving 2 or more of the following vascular territories: coronary arteries, cerebral arteries, or peripheral arteries), and found no significant differences in the risk of non-fatal stroke between the liraglutide and the placebo groups.92 This study was not included in our meta-analysis of recurrent stroke prevention since it does not provide specific data for the subgroup of patients with history of stroke. To date, no secondary analyses have been conducted to study the effects of dulaglutide, exenatide, lixisenatide, albiglutide, or oral semaglutide for recurrent stroke prevention.

RecommendationsIn patients with DM2 and history of stroke, pioglitazone may be added to standard antidiabetic treatment to prevent stroke recurrence (class IIb recommendation, level of evidence B).

The available evidence is insufficient to recommend adding SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists to standard antidiabetic treatment in patients with DM2 and history of stroke to prevent stroke recurrence.

Additional commentsThe risk of heart failure should be assessed in patients with DM2 and history of stroke who are eligible for treatment with pioglitazone. Furthermore, randomised clinical trials evaluating the global vascular benefits of antidiabetic drugs, including a total of 7711 patients with history of cerebrovascular disease or stroke (13.7% of the total population included in these studies) have shown that GLP-1 receptor agonists significantly decrease the risk of stroke; it therefore seems reasonable to add GLP-1 receptor agonists to standard antidiabetic treatment in patients with DM2 and history of stroke.

PICO 5: In patients with DM2 and history of stroke, does adding antidiabetic drugs with cardiovascular benefits to standard antidiabetic treatment reduce the overall risk of vascular complications as compared to administering standard antidiabetic treatment alone?ThiazolidinedionesThe PROactive trial is the only clinical trial of pioglitazone that has published data on the effects of the drug in the subgroup of patients with history of stroke,40 reporting a 27% decrease in the RR of vascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke (Fig. 6).

SGLT2 inhibitorsIn the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, empagliflozin did not provide significant benefits in the prevention of vascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal stroke in the subgroup of patients with history of cerebrovascular disease.59 A secondary publication of the CANVAS programme, analysing the effects of canagliflozin in patients with history of cerebrovascular disease, observed no benefit on the composite endpoint of vascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke (HR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.75-1.23).64 This trial was not included in our meta-analysis since raw numerical data are not provided. The CREDENCE and DECLARE TIMI 58 trials have not reported specific data on the effects of canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, respectively, on the overall risk of vascular events in patients with history of stroke.

GLP-1 receptor agonistsThe HARMONY trial87 is the only clinical trial providing data on the analysis of global vascular benefit (decrease in the risk of vascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke) in the subgroup of patients with history of stroke, showing a trend toward a decrease in the risk of the composite endpoint (Fig. 6).

Post-hoc analyses of the LEADER, SUSTAIN 6, and REWIND trials have evaluated the effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide in the subgroup of patients with history of stroke or myocardial infarction.78,82,89 Both liraglutide (HR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.99)82 and dulaglutide (HR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.96)89 were found to significantly reduce the risk of vascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke in patients with history of stroke or myocardial infarction.

RecommendationsIn patients with DM2 and history of stroke, pioglitazone may be added to standard antidiabetic treatment to prevent vascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (class IIa recommendation, level of evidence B).

In patients with DM2 and history of stroke, GLP-1 receptor agonists may be added to standard antidiabetic treatment to prevent vascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (class IIb recommendation, level of evidence B).

In patients with DM2 and history of stroke, we do not recommend adding SGLT2 inhibitors to standard antidiabetic treatment for the prevention of vascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (class III recommendation, level of evidence B).

Additional commentsRandomised clinical trials evaluating the global vascular benefits of antidiabetic drugs, including a total of 7711 patients with history of cerebrovascular disease or stroke (13.7% of the total population included in these studies), have shown that GLP-1 receptor agonists significantly decrease the risk of vascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke. Furthermore, post-hoc analyses of the HARMONY, LEADER, and REWIND trials report a global vascular benefit in patients with history of stroke or myocardial infarction. It therefore seems reasonable to add GLP-1 receptor agonists to standard antidiabetic treatment in patients with DM2 and history of stroke.

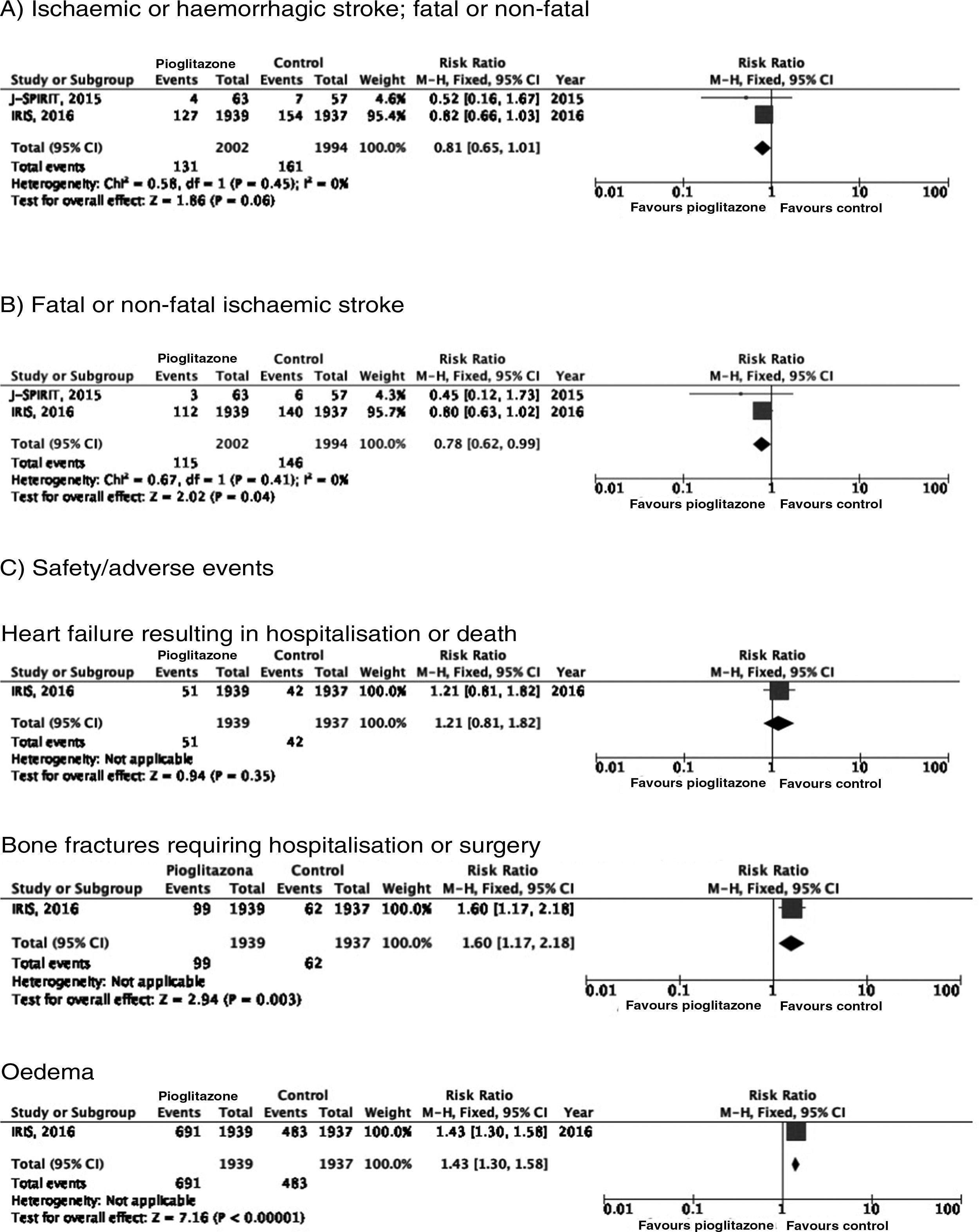

PICO 6: In patients with history of stroke and insulin resistance or prediabetes, do antidiabetic drugs with global vascular benefit reduce the risk of stroke recurrence as compared to placebo?We identified 2 clinical trials including patients with history of stroke and insulin resistance or prediabetes and analysing whether treatment with an antidiabetic drug modifies the risk of stroke recurrence: the J-SPIRIT93 and IRIS trials.94–96 Both trials analysed the effects of pioglitazone; to date, no clinical trials have assessed the use of other antidiabetic drugs for secondary stroke prevention in patients with prediabetes or insulin resistance. The criteria used for defining insulin resistance differed between trials. In the J-SPIRIT trial, the definition was based on the results of an oral glucose tolerance test, whereas the IRIS trial evaluated insulin resistance using the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR). The open-label J-SPIRIT trial failed to reach the pre-established sample size; with only 120 participants, it did not achieve the necessary statistical power to provide definitive conclusions.93 The IRIS trial included 3876 patients; the primary outcome was fatal or non-fatal stroke or myocardial infarction, and stroke recurrence was studied as a secondary outcome.95 The meta-analysis of the results of both trials shows a non-significant decrease in the RR of ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke in this population; nevertheless, when the analysis only considered recurrence of ischaemic stroke, pioglitazone did significantly reduce the RR to 22%. Regarding safety, a significant increase was observed in the risk of oedema and bone fractures requiring surgery or hospitalisation, whereas no significant differences were observed in the risk of heart failure resulting in hospitalisation or death (Fig. 7).

In patients with prediabetes or insulin resistance and history of stroke, pioglitazone may be added to standard antidiabetic treatment to prevent recurrence of ischaemic stroke (class IIb recommendation, level of evidence B).

In patients with prediabetes or insulin resistance and history of stroke, the available evidence is insufficient to recommend the administration of SLGT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists due to a lack of clinical trials in this population.

Additional commentsOur meta-analysis only included data from the original publication of the IRIS trial. However, a secondary analysis applied different criteria for identifying cases of stroke, and also included all patients with neurological symptoms of less than 24 hours’ progression but presenting lesions on neuroimaging studies; this resulted in an additional 48 cases of ischaemic stroke (14 in the pioglitazone group and 34 in the control group). An updated analysis with these data showed that the drug was associated with a significant decrease of 25% for the RR of stroke of any cause and 28% for ischaemic stroke, but had no effect on the risk of haemorrhagic stroke.96 As an additional benefit in patients with insulin resistance or prediabetes and history of stroke, pioglitazone has been found to reduce the RR of developing DM2 at 5 years by 53%.97 The IRIS trial also analysed the effect of pioglitazone on the risk of cognitive impairment, reporting no impact on cognitive function at 5 years.98 A secondary publication of the IRIS trial reported a RR of 47% for bone fractures attributable to pioglitazone use, with an absolute risk of 1.6 at 5 years; patients starting treatment with pioglitazone should be advised about this adverse effect to prevent falls, and should undergo screening and treatment for osteoporosis.99

DiscussionIn this systematic review and meta-analysis, we posed a series of questions that we deemed relevant for guiding stroke prevention strategies in patients with DM2 or prediabetes. Firstly, we evaluated the available evidence on the effect of tight glycaemic control on stroke prevention. Secondly, we analysed the available data on the use of antidiabetic drugs for reducing the risk of stroke.

Both the target values for intensive glycaemic treatment (decreasing HbA1c levels below an absolute or relative threshold) and the strategies used differed between the 3 trials evaluating the effect of glycaemic control. This complicated the task of establishing recommendations based on a single HbA1c threshold; therefore, our meta-analysis classified patients according to whether they were assigned to receive intensive or standard glycaemic treatment. According to the results of each of the clinical trials included in our analysis and data from our meta-analysis, tight glycaemic control does not seem to reduce the risk of stroke. However, in view of the benefits of glycaemic control for preventing microvascular events, different diabetes associations recommend a glycaemic target of HbA1c < 7% in patients with DM2 and no history of severe hypoglycaemia, without severe macrovascular disease or associated comorbidities, with good life expectancy, or without difficulties achieving tight glycaemic control.14,19 Lastly, our systematic review did not identify any study specifically analysing the effect of tight glycaemic control on the prevention of stroke recurrence in patients with DM2 and history of stroke; we are therefore unable to issue specific recommendations for secondary stroke prevention.

The FDA requirement of evaluating the vascular risk of antidiabetic drugs has brought to light their benefits for reducing the risk of stroke and other vascular complications in patients with DM2 and high vascular risk or established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. GLP-1 receptor agonists have been shown to be useful for primary prevention of stroke, whereas pioglitazone seems to help prevent stroke recurrence or other vascular complications in patients with history of stroke. However, our systematic review is not without limitations. Firstly, no clinical trial has been designed specifically to evaluate the effect of antidiabetic drugs on the risk of stroke; our recommendations are therefore based on the analysis of stroke risk as a secondary outcome of the included clinical trials or on post-hoc analyses of these trials. Furthermore, no data are available for some families of antidiabetic drugs, and their effects in some of the scenarios presented in this document therefore could not be evaluated. Lastly, for patients with prediabetes and history of stroke, the only available data come from clinical trials of pioglitazone; we are therefore unable to conclude whether other drug groups are efficacious in these patients.

In conclusion, while there is no evidence that tight metabolic control reduces the risk of stroke, some families of antidiabetic drugs with vascular benefits have been shown to reduce the risk of stroke when added to standard antidiabetic treatment, showing efficacy both for primary prevention, in patients with DM2 and high vascular risk or established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and for secondary prevention of stroke in patients with DM2 or prediabetes. Neurologists should be familiar with the characteristics and benefit/risk ratios of antidiabetic drugs with a view to their inclusion in prevention strategies for stroke and other vascular complications in patients with DM2 or prediabetes.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestBlanca Fuentes has received lecture honoraria and consulting fees from Novonordisk. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Fuentes B, Amaro S, Alonso de Leciñana M, Arenillas JF, Ayo-Martín O, Castellanos M, et al. Prevención de ictus en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 o prediabetes. Recomendaciones del Grupo de Estudio de Enfermedades Cerebrovasculares de la Sociedad Española de Neurología. Neurología. 2021;36:305–323.