A new model permitting free choice of hospital has been introduced in the Region of Madrid. This may result in changes in how outpatient neurological care is provided and managed. The purpose of this study is to analyse initial visits to a general neurology department in the Region of Madrid and record the health district corresponding to each patient's residence.

MethodsObservational and prospective study of a cohort of patients making initial outpatient visits to a neurology department between 16 September 2013 and 16 January 2014.

ResultsThe study included 1109 patients (63.8% women, mean age 55.2±20.5). The most frequent diagnostic groups were periodic headache, cognitive disorders, and neuromuscular diseases. Non-neurological diseases were diagnosed in 1.1% of the cases. The mean time of delay was 7.2±5.1 days. Residents within the hospital's health district made up 73.8% of the total, while 26.2% chose a hospital outside of the health district corresponding to their residences. In the latter group, 59.5% made the choice based on the level of care offered, while 39.7% changed hospitals due to shorter times to consultation. The patients who came from another health district were younger (50.7 vs. 57.3, P<.0001) and had a lower rate of discharges on the first visit (16.4% vs. 30.1%, P<.0001).

ConclusionThe model of free choice of hospital delivers significant changes in healthcare management and organisation. Reasons given for choosing another hospital are more ample experience and shorter delays with respect to the home district hospital. Management of patients from outside the health district is associated with greater complexity.

En la Comunidad de Madrid se ha desarrollado un nuevo sistema de libertad de elección de área sanitaria, que puede suponer un cambio en la asistencia sanitaria neurológica y su gestión. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar las primeras visitas de Neurología general atendidas en un área sanitaria de Madrid, teniendo en cuenta el área sanitaria de procedencia del paciente.

MétodosEstudio observacional, prospectivo, de una cohorte de primeras visitas de neurología ambulatoria realizadas entre el 16 de septiembre del 2013 y el 16 de enero del 2014.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 1.109 pacientes (63,8% mujeres, edad media 55,2±20,5 años). Las categorías diagnósticas más frecuentes fueron cefalea periódica, trastornos cognitivos y patología neuromuscular. El 1,1% se consideró patología no neurológica. El tiempo medio de demora fue de 7,2 ± 5,1 días. El 73,8% perteneció a la propia área sanitaria del hospital, mientras que el 26,2% procedió de otra área por libertad de elección. De estos, el 59,5% acudió por excelencia, mientras que el 39,7% por una menor demora. Los pacientes que acudieron por libre elección tuvieron una edad media menor (50,7 vs. 57,3 años; p<0,0001) y una menor tasa de altas en la primera visita (16,4% vs. 30,1%; p<0,0001).

ConclusiónEl modelo de libre elección de la asistencia neurológica implica un cambio relevante en la gestión sanitaria. La búsqueda de centros a los que se atribuye mayor excelencia y con menor demora son motivos para la libertad de elección, asociándose los pacientes de otra área a una mayor complejidad.

The last few years have witnessed significant improvements in outpatient and non-hospital neurological care.1–4 The rising frequency of neurological diseases, their growing social and care-related repercussions, and deeper knowledge of the diseases themselves all contribute to the higher demand for neurological consultations.5 In Spain, the General Law on Healthcare of 1986 established creating health care districts to serve as the basic building blocks of the healthcare system, whether for primary care or specialist care.6 Since then, several studies have examined outpatient neurological care in different regions of our country.7–22 These studies were conducted as a means to improving health planning and care.23,24

In 2010, the Region of Madrid implemented a system in which patients may freely choose their doctors and hospitals, including specialists; this change resulted in the unified health district of the Region of Madrid.25–27 This system differed greatly from the previous one that had been established by the General Law on Healthcare. Within the new framework, the patient may freely consult with specialists or a department from another health district, and this may mean major changes in health planning. These changes in turn may affect outpatient neurological care, which is a relevant consideration for healthcare management.

The purpose of this study was to analyse the first neurological consultations in one health district in Madrid to obtain demographic, diagnostic, and care-related data. We noted whether patients resided in the same health district in which the study was carried out, or if they had specifically chosen to seek care in that district.

Material and methodsSpecialist neurological care in the Region of Madrid is provided in 27 zones that are geographically equivalent to the health districts established by the previous system. Each health district is headed by a hospital, and care is provided in that hospital or in its corresponding specialist care centres.

Outpatient neurological care in District 7 is headed by Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Care is provided in that hospital's facilities, at the Modesto Lafuente specialist care centre, or at the Avenida de Portugal specialist care centre. Throughout 2013, care was provided to 38,214 patients; 6311 were seen by general neurologists for the first time following a referral from primary care doctors, and 1063 of them had opted to use our healthcare centres. The rest of the patients received care from more specific units within the neurology department.

This observational prospective study examined a cohort of patients receiving outpatient general neurology care for the first time. Patients seen between 16 September 2013 and 16 January 2014 were recruited consecutively. Our team recorded demographic and clinical variables (age, sex, diagnostic category) for all patients examined during this time period in the consulting rooms of 3 neurologists at either Hospital Clínico San Carlos (JAM, JM) or at the Modesto Lafuente specialist care centre (JAM, RG). Diagnostic categories included the following: periodic headache; acute headache; cognitive disorder; parkinsonism; tremor (excluding parkinsonism); other movement disorders, seizure, syncope, and epilepsy; stroke and other cerebrovascular diseases; multiple sclerosis; neuro-ophthalmic disease; neuropathic pain; lumbar and disc disorders; neuromuscular disease; dizziness, instability, and vertigo; brain tumours; phakomatoses, malformations, and genetic concerns; non-specific neurological symptoms; psychiatric disorders; administrative referrals; and non-neurological disease.

We also recorded the following care-related variables:

- –

Delay to care, defined as the time in days between the patient's referral and the date of his or her appointment with the neurologist, including non-working days. This entry reported the date on which the patient was evaluated by the referring primary care doctor or specialist, as well as the date of discharge from the emergency department or the hospital.

- –

The patient's referral route: primary care, specialist care, hospitalisation, or emergency department care.

- –

The patient's health district of residence. Patients who specifically chose our centre and those residing in the district served by Hospital Clínico. Patients who had opted for our district were asked whether their choice was based on the centre's reputation, greater delays elsewhere, or both reasons.

- –

Which patients were being monitored by the neurology department.

- –

Patients who had been referred for a second opinion following an examination of the same condition by primary care doctors.

- –

The patient's management outcome, recorded as one of the following options: referral to a specific unit within the neurology department, referral to the emergency department, ordering tests, referral to a different specialty, or discharge.

Results were analysed with IBM® SPSS® statistical software, version 20.0 for Mac. Data are given as means±standard deviation and as frequencies (percentages). Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square test for qualitative variables. The t test for independent samples was used to compare both qualitative and quantitative variables.

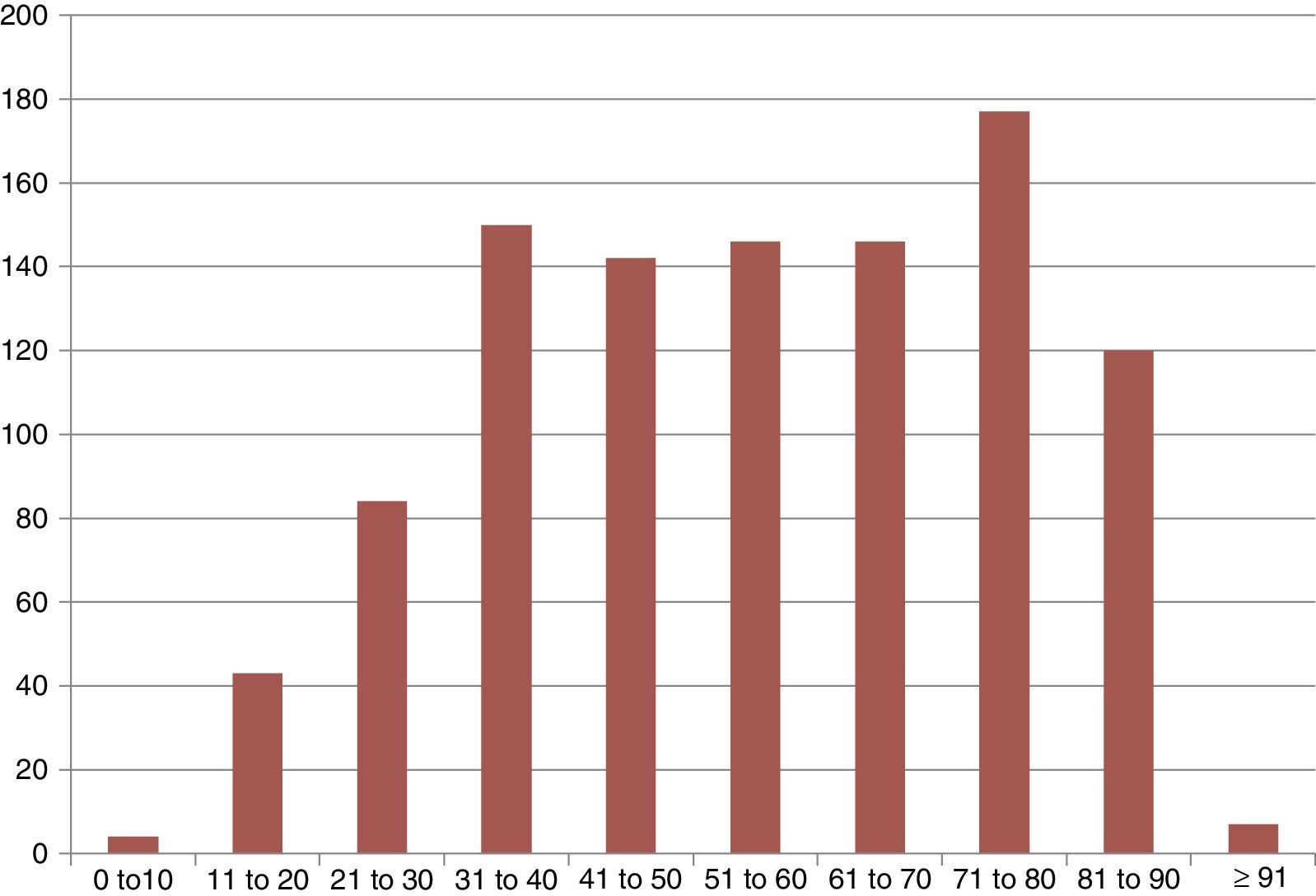

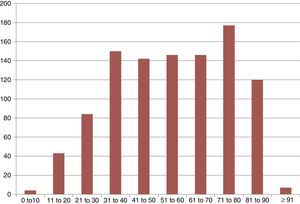

ResultsWe included 1109 patients with a mean age of 55.2±20.5 years; 707 were women (63.8%). The mean age of men was 55.6±20.6 years, whereas the mean age of women was 55.1±20.5 years (P=.689). Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the sample by age groups. Ninety patients (8.1%) did not show up for their appointments.

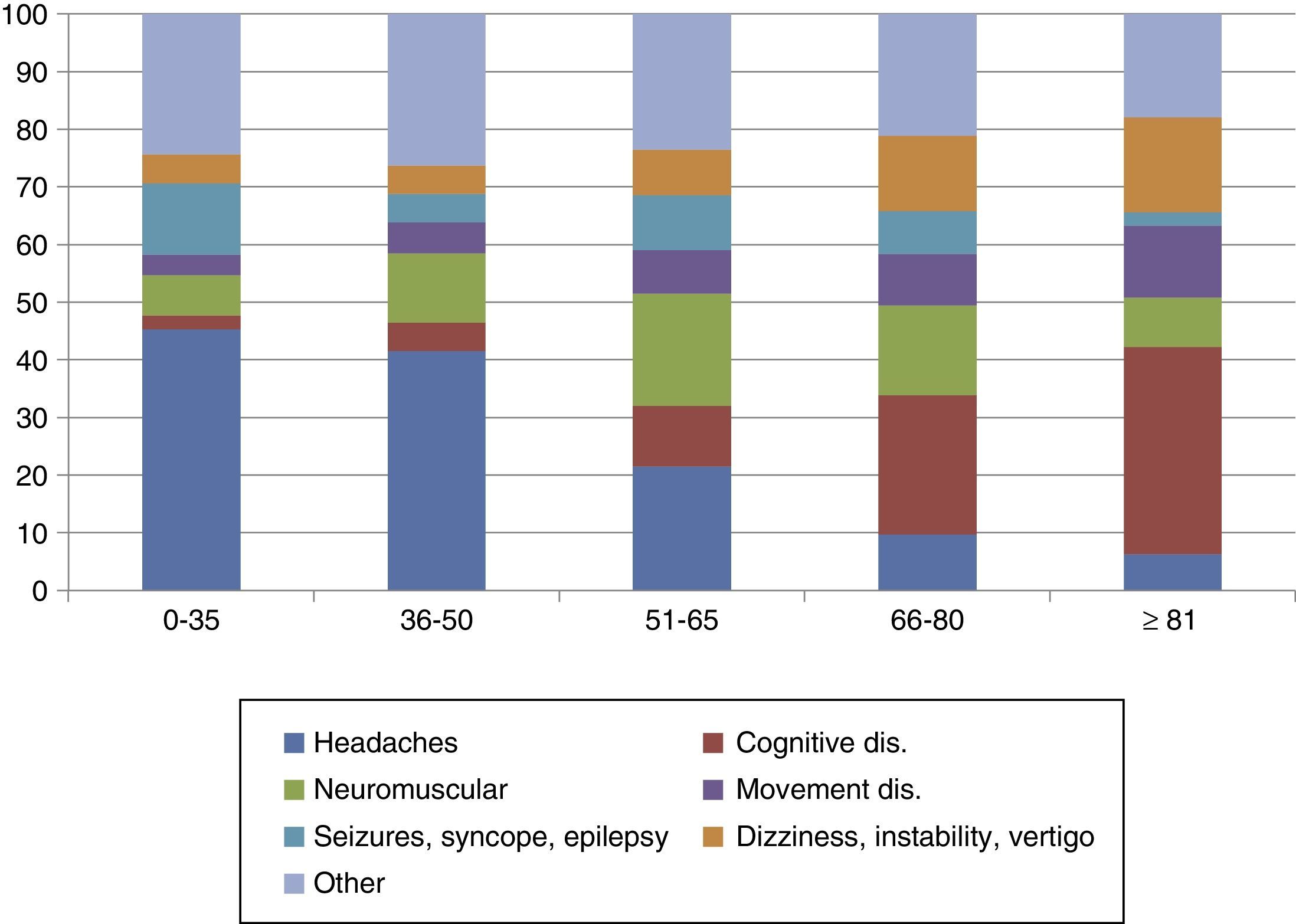

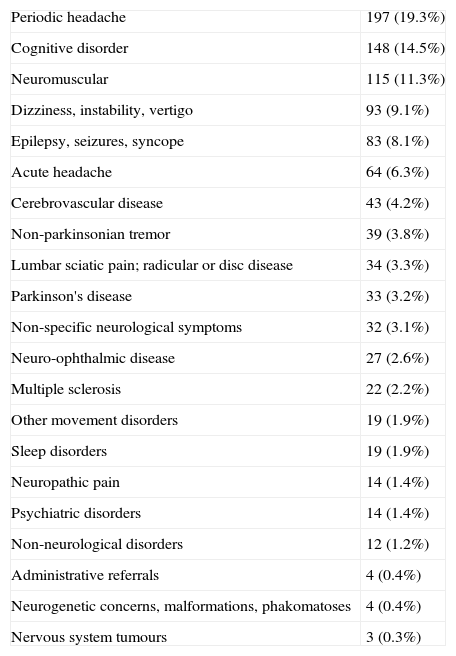

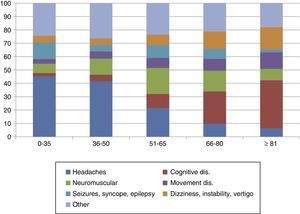

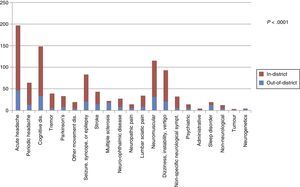

Among patients who did attend, the most common diagnostic categories were periodic headache (197; 19.3%); cognitive disorder (148; 14.5%); neuromuscular disease (115; 11.3%); dizziness, instability, or vertigo (93; 9.1%); seizures, syncope, and epilepsy (83; 8.1%); and acute headache (64; 6.3%). Other reasons for consultation are given in Table 1. A non-neurological disorder was diagnosed in 12 cases (1.1%). There was an association between diagnostic categories and patients’ ages, as can be observed in Fig. 2.

Diagnostic categories in the sample.

| Periodic headache | 197 (19.3%) |

| Cognitive disorder | 148 (14.5%) |

| Neuromuscular | 115 (11.3%) |

| Dizziness, instability, vertigo | 93 (9.1%) |

| Epilepsy, seizures, syncope | 83 (8.1%) |

| Acute headache | 64 (6.3%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 43 (4.2%) |

| Non-parkinsonian tremor | 39 (3.8%) |

| Lumbar sciatic pain; radicular or disc disease | 34 (3.3%) |

| Parkinson's disease | 33 (3.2%) |

| Non-specific neurological symptoms | 32 (3.1%) |

| Neuro-ophthalmic disease | 27 (2.6%) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 22 (2.2%) |

| Other movement disorders | 19 (1.9%) |

| Sleep disorders | 19 (1.9%) |

| Neuropathic pain | 14 (1.4%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 14 (1.4%) |

| Non-neurological disorders | 12 (1.2%) |

| Administrative referrals | 4 (0.4%) |

| Neurogenetic concerns, malformations, phakomatoses | 4 (0.4%) |

| Nervous system tumours | 3 (0.3%) |

Mean delay to care was 7.2±5.1 days. Primary care was responsible for referring 880 patients (86.4%); 92 (9.0%) were referred by specialists, 42 (4.1%) by the emergency department, and 5 (0.5%) by a different hospital ward. Thirty patients (2.9%) requested a second opinion after having consulted with a private doctor. Ninety patients (8.1%) did not attend the appointment, while 58 (5.2%) were already being monitored by our department. Regarding outcomes of the patients we examined, 271 were discharged (26.6%), 709 required an examination or consultation in a specific unit in the neurology department (69.5%), 32 were referred to another specialty (3.1%), and 7 were referred to the emergency department (0.7%). Additional tests were ordered for 313 cases (30.7%).

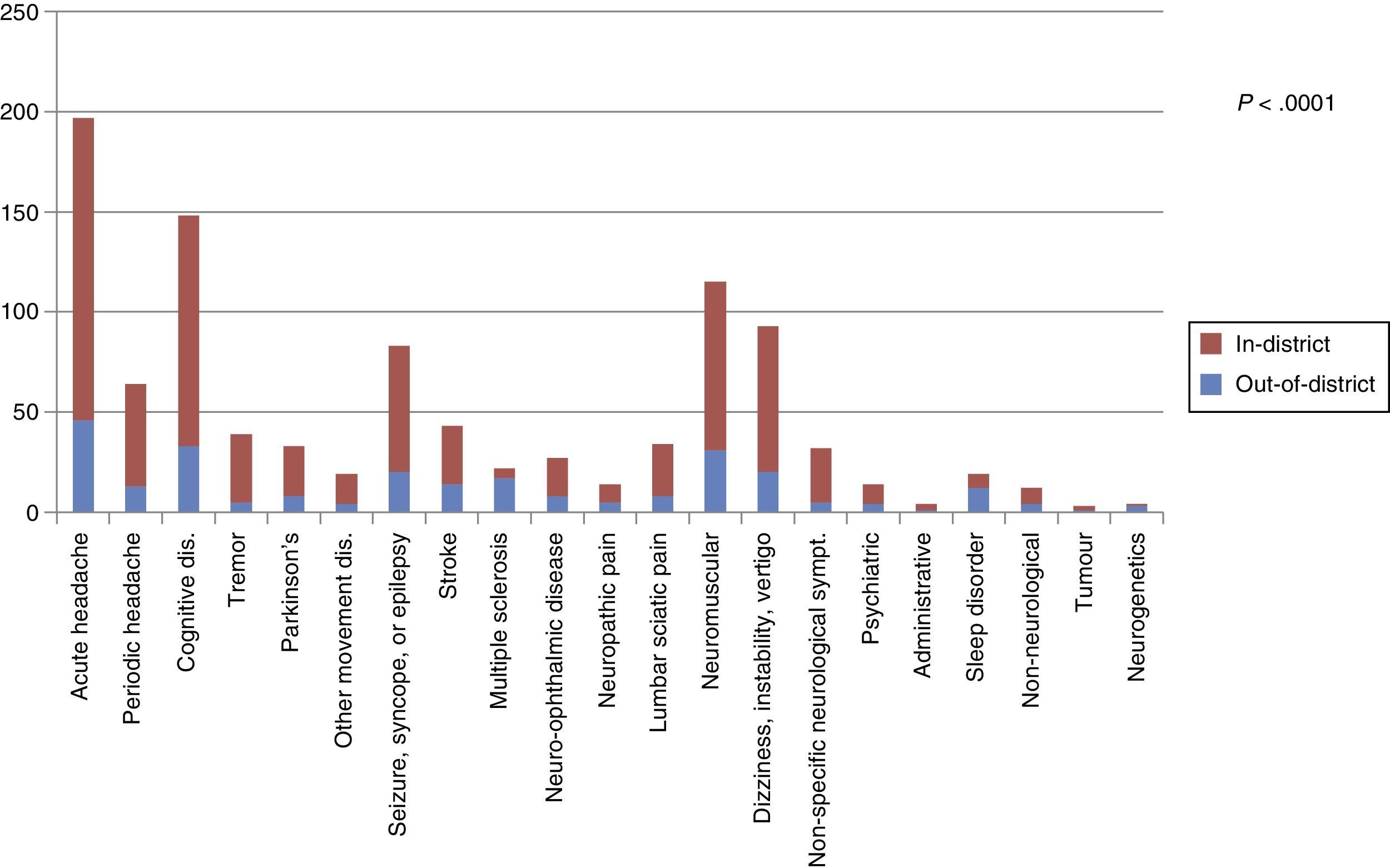

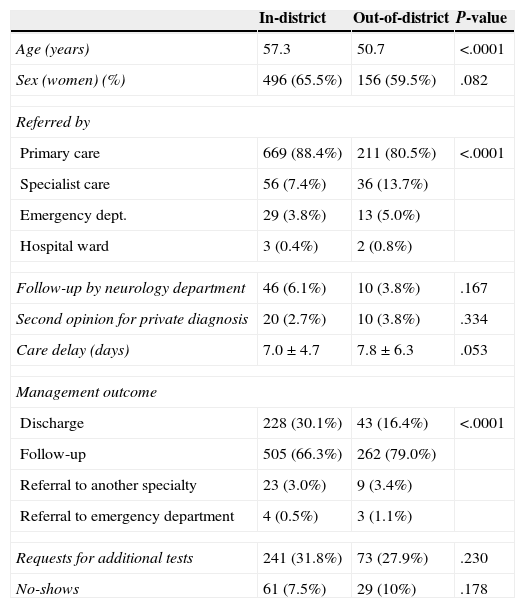

Broken down by health district, 818 of the total resided in the zone corresponding to the hospital (73.8%); 291 resided in another zone (26.2%). Of the patients who attended their appointments 262 specifically opted for our facilities (25.7%). Compared to patients residing in our zone, those who opted for our facilities were younger (mean age 50.7±20.2 out-of-district vs. 57.3±20.3 in-district; P=.0001). Out-of-district patients also showed a lower percentage of women (59.7% out-of-district vs. 65.5% in-district; P=.082). More patients in the out-of-district group had been referred by specialists and emergency departments than in the other group (80.5% referred by primary care for out-of-district vs. 88.4% in-district; 13.7% by specialists for out-of-district vs. 7.4% in-district; 5.0% by emergency departments for out-of-district vs. 3.8% in-district. P=.011). The percentage of no-shows was similar between out-of-district (10%) and in-district patients (7.5%), P=.178 (Table 2). The two groups showed statistically significant differences with regard to both diagnostic category and management outcome (Table 2).

Demographic and care-related factors for in-district vs. out-of-district patients.

| In-district | Out-of-district | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.3 | 50.7 | <.0001 |

| Sex (women) (%) | 496 (65.5%) | 156 (59.5%) | .082 |

| Referred by | |||

| Primary care | 669 (88.4%) | 211 (80.5%) | <.0001 |

| Specialist care | 56 (7.4%) | 36 (13.7%) | |

| Emergency dept. | 29 (3.8%) | 13 (5.0%) | |

| Hospital ward | 3 (0.4%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Follow-up by neurology department | 46 (6.1%) | 10 (3.8%) | .167 |

| Second opinion for private diagnosis | 20 (2.7%) | 10 (3.8%) | .334 |

| Care delay (days) | 7.0±4.7 | 7.8±6.3 | .053 |

| Management outcome | |||

| Discharge | 228 (30.1%) | 43 (16.4%) | <.0001 |

| Follow-up | 505 (66.3%) | 262 (79.0%) | |

| Referral to another specialty | 23 (3.0%) | 9 (3.4%) | |

| Referral to emergency department | 4 (0.5%) | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Requests for additional tests | 241 (31.8%) | 73 (27.9%) | .230 |

| No-shows | 61 (7.5%) | 29 (10%) | .178 |

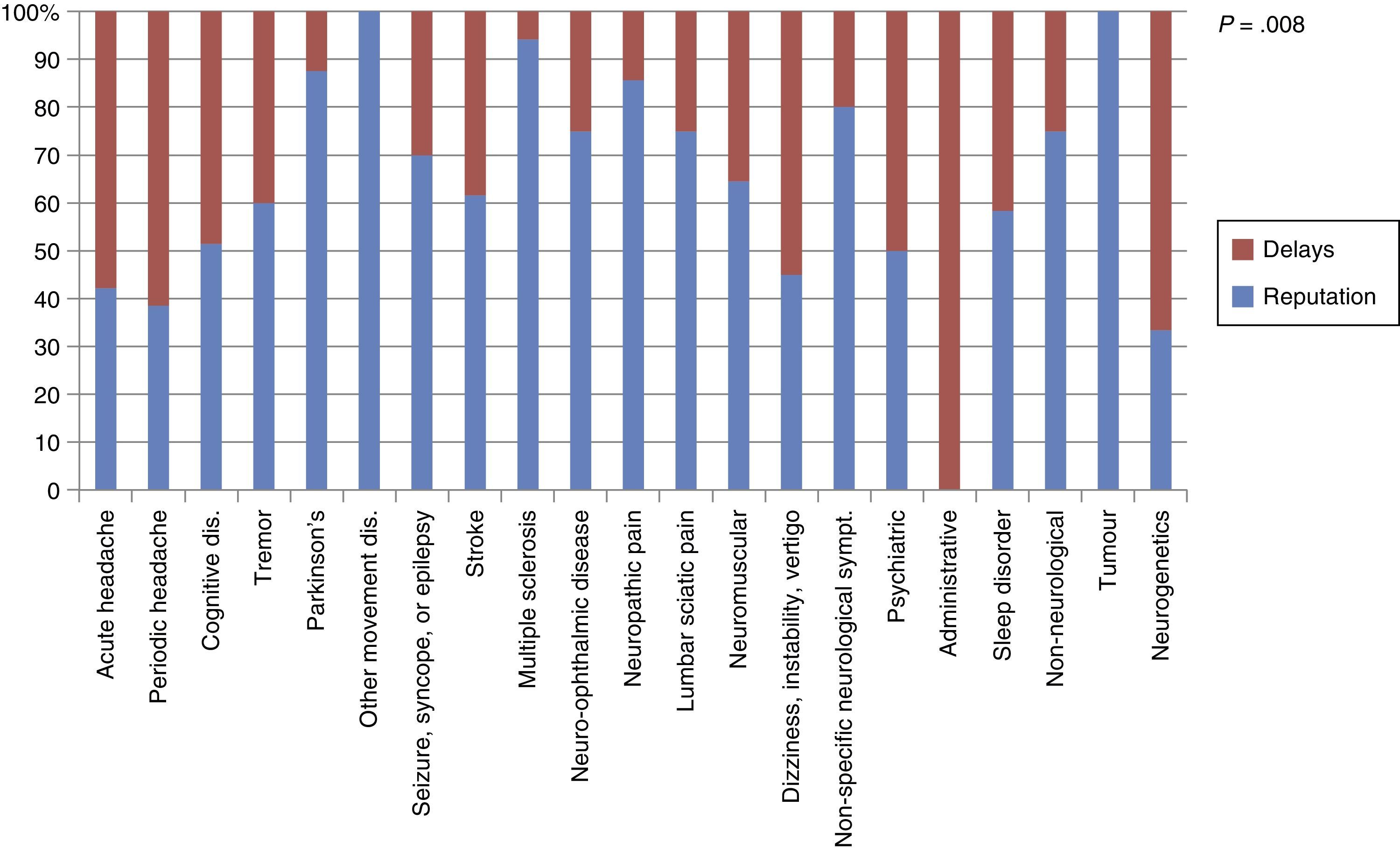

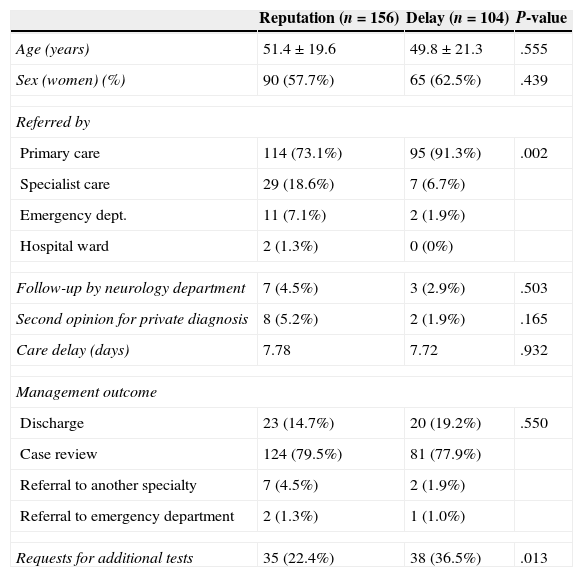

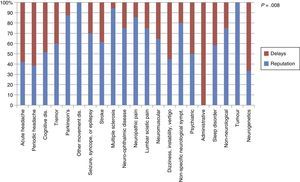

Of the out-of-district group, 156 patients (59.5%) stated that they had chosen the medical centre based on its reputation, whereas 104 patients (39.7%) indicated that delays were longer in their home health districts. Two patients (0.8%) stated that they had chosen neurological care in our district due to both reasons. In successive analyses comparing the group citing reputation and the one citing delay times, we excluded the 2 patients pointing to both motives. Results from comparing these groups are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3. Diagnostic categories also differed between the in-district and out-of-district groups (Fig. 4).

Demographic and care-related factors and reason for choosing our district.

| Reputation (n=156) | Delay (n=104) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.4±19.6 | 49.8±21.3 | .555 |

| Sex (women) (%) | 90 (57.7%) | 65 (62.5%) | .439 |

| Referred by | |||

| Primary care | 114 (73.1%) | 95 (91.3%) | .002 |

| Specialist care | 29 (18.6%) | 7 (6.7%) | |

| Emergency dept. | 11 (7.1%) | 2 (1.9%) | |

| Hospital ward | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Follow-up by neurology department | 7 (4.5%) | 3 (2.9%) | .503 |

| Second opinion for private diagnosis | 8 (5.2%) | 2 (1.9%) | .165 |

| Care delay (days) | 7.78 | 7.72 | .932 |

| Management outcome | |||

| Discharge | 23 (14.7%) | 20 (19.2%) | .550 |

| Case review | 124 (79.5%) | 81 (77.9%) | |

| Referral to another specialty | 7 (4.5%) | 2 (1.9%) | |

| Referral to emergency department | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Requests for additional tests | 35 (22.4%) | 38 (36.5%) | .013 |

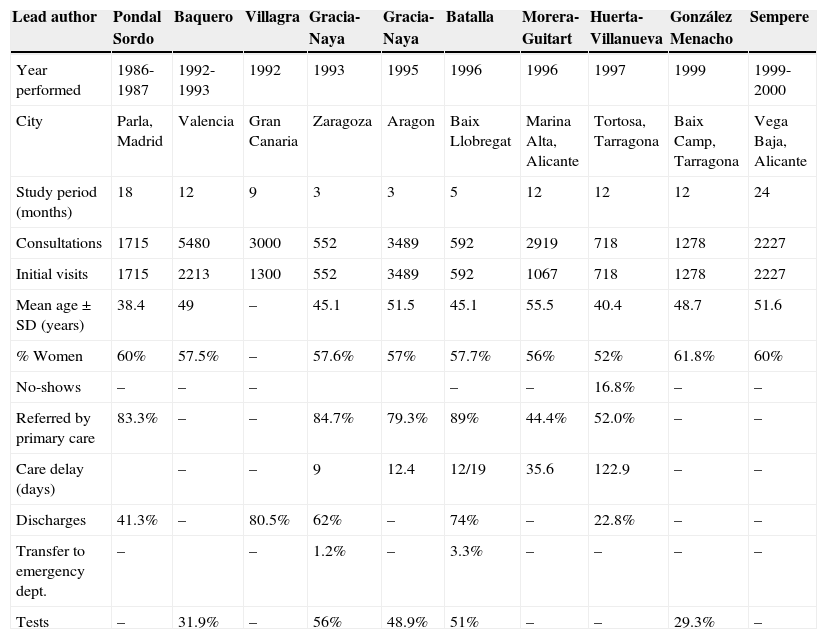

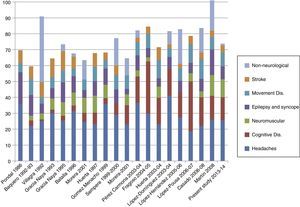

The demand for healthcare may fluctuate over time, and it responds to a series of sociodemographic, care-related, use-related and economic factors.24 These factors must be understood to foster good healthcare planning.28 Different studies carried out in Spain have examined activity within outpatient neurology clinics and recorded relevant demographic, clinical, and care-related factors. Mean age in our study is similar to that reported by other comparable studies performed in the past few years. These data suggest that mean patient age has risen with respect to studies performed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but also that mean age has remained stable since the late 1990s and early 2000s. The percentage of women underwent a similar change and has also stabilised at 60%-63% according to the most recent studies (Table 4).

Comparison of studies conducted in Spain.

| Lead author | Pondal Sordo | Baquero | Villagra | Gracia-Naya | Gracia-Naya | Batalla | Morera-Guitart | Huerta-Villanueva | González Menacho | Sempere |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year performed | 1986-1987 | 1992-1993 | 1992 | 1993 | 1995 | 1996 | 1996 | 1997 | 1999 | 1999-2000 |

| City | Parla, Madrid | Valencia | Gran Canaria | Zaragoza | Aragon | Baix Llobregat | Marina Alta, Alicante | Tortosa, Tarragona | Baix Camp, Tarragona | Vega Baja, Alicante |

| Study period (months) | 18 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Consultations | 1715 | 5480 | 3000 | 552 | 3489 | 592 | 2919 | 718 | 1278 | 2227 |

| Initial visits | 1715 | 2213 | 1300 | 552 | 3489 | 592 | 1067 | 718 | 1278 | 2227 |

| Mean age±SD (years) | 38.4 | 49 | – | 45.1 | 51.5 | 45.1 | 55.5 | 40.4 | 48.7 | 51.6 |

| % Women | 60% | 57.5% | – | 57.6% | 57% | 57.7% | 56% | 52% | 61.8% | 60% |

| No-shows | – | – | – | – | – | 16.8% | – | – | ||

| Referred by primary care | 83.3% | – | – | 84.7% | 79.3% | 89% | 44.4% | 52.0% | – | – |

| Care delay (days) | – | – | 9 | 12.4 | 12/19 | 35.6 | 122.9 | – | – | |

| Discharges | 41.3% | – | 80.5% | 62% | – | 74% | – | 22.8% | – | – |

| Transfer to emergency dept. | – | – | 1.2% | – | 3.3% | – | – | – | – | |

| Tests | – | 31.9% | – | 56% | 48.9% | 51% | – | – | 29.3% | – |

| Lead author | Morera-Guitart | Pérez-Carmona | Fragoso | Huerta-Villanueva | López-Domínguez | López-Hernández | López-Pousa | Casado Menéndez | Martín | Present study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year performed | 2001 | 2003-2004 | 2004-2005 | 2003-2004 | 2005-2006 | 2005-2006 | 2006-2007 | 2006-2008 | 2008 | 2013-2014 |

| City/Province | Marina Alta, Alicante | Marina Baixa, Alicante | Rubí, Barcelona | Tortosa, Tarragona | Huelva | Elche, Alicante | Girona | Gijón | Burgos | Madrid |

| Study period (months) | 12 | 2 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 18 | 12 | 4 |

| Consultations | 3301 | 1000 | 1460 | 1004 | 500 | 3937 | 1078 | 1000 | 1341 | 1109 |

| Initial visits | 1494 | 265 | 496 | 1004 | 500 | 3937 | 1078 | 1000 | 1341 | 1109 |

| Mean age (years) | 60.4 | 55.0 | – | 56.7 | 51 | 56.8 | 60.6 | 62.04 | 56.2 | 55.2 |

| % Women | 57% | 52.8% | – | 62% | 63.4% | 62% | 61.4% | 59.8% | 60.9% | 63.8 |

| No-shows | – | 9.8% | 23.79% | 20.8% | – | 18% | – | 16% | 12% | 8.1% |

| Referred by primary care | 51.6% | – | – | 69.3% | – | 93.9% | – | 61.5% | 76% | 86.4% |

| Care delay (days) | 43.8 | – | – | 165.4 | – | 30.6 | – | – | – | 7.2 |

| Discharges | – | 17.7% | 9.2% | 21.1% | 40.2% | 42% | – | 50.4% | 59% | 26.6 |

| Transfer to emergency dept. | – | – | – | – | 1% | – | – | – | 0.7% | |

| Tests | – | – | – | 55% | 34% | – | – | – | 30.7% |

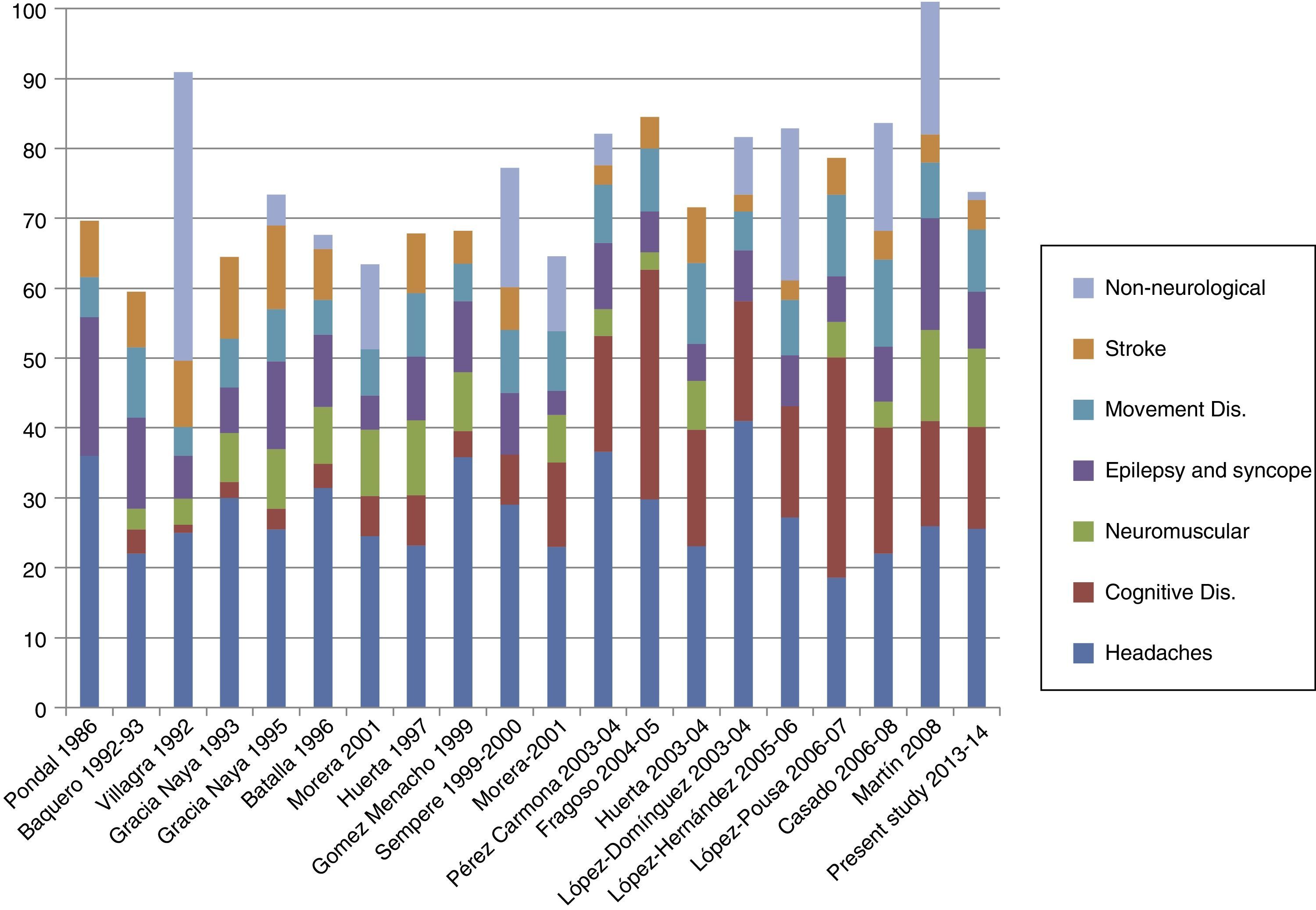

In our cohort, headaches were the most common motive for consultation, followed by cognitive disorders. Most of the similar studies performed in recent years also cite cognitive disorders as the second most common concern. The increased presence of cognitive disorders in neurology clinics has also been highlighted by studies performed in the same health district during 2 different time periods.5,17Fig. 5 displays a comparison of the most frequent diagnostic categories reported by different studies.

One of the most interesting results from our study was the low percentage of non-neurological diagnoses. In fact, this rate was far lower than those observed in other earlier studies,9,11,12,14,15,18,19,21,22,29 which is indicative of better selection of the neurological cases referred to us. Despite the above, we cannot rule out the possibility of discrepancies in the definition of ‘non-neurological disease’ between these very different studies. For example, other studies have included syncope or subjective memory loss within the non-neurological category14,18; nevertheless, these symptoms may require assessment by a neurologist in order to rule out neurological disease in differential diagnosis, so we have not classified them as non-neurological. In any case, this lower percentage of non-neurological disease may be responsible for the lower rate of re-referral after the initial consultation compared to some earlier studies (here, the rate reached 60% or even 80%). This suggests greater awareness of the criteria for referral to a neurologist.30

Another key aspect is the percentage of no-shows, which was also lower than in earlier studies providing these figures.31,32 As demonstrated in prior studies,32 fewer no-shows might be the result of shorter waiting times, which would decrease the number of patients forgetting appointments and finding alternative care providers.

In our study, 26.2% of the patient total resided out of our health district. This percentage is rather high and indicates that many patients take advantage of the option of choosing their medical centre. The 2 main motives given by patients opting for out-of-district care are the hospital's reputation, cited by 59.5%, and the waiting times in the case of the remaining 39.7%. Patients who chose the health district based on its reputation may also do so for a variety of motives. Examples include prior direct or indirect experience with the department or hospital, geographical convenience, the primary care doctor's recommendation, and the care delay compared to other centres, since there are several neurology departments operating in the Region of Madrid.

On the other hand, the out-of-district patients who choose our hospital have a lower rate of re-referrals on the first visit, but more referrals to specialised units and higher rates of follow-up within the same department. This tendency remains when we analyse only those patients opting for our district because of care delays elsewhere. This indicates that patients who decide to use another healthcare district, even those citing different motives, constitute a subgroup whose cases are more complex and may consequently require more resources.

In conclusion, having the option of choosing one's public provider of neurological care in the Region of Madrid implies major changes for healthcare management, since many patients do explore their care options out-of-district. Although care delays may affect the patient's decision, patients will also seek out centres said to have greater experience or better results in specific areas. As a result, out-of-district patients present more complex cases than do in-district patients. A comparison with similar published studies shows that our results indicate a higher rate of consultations for cognitive disorders and a lower rate of patients with non-neurological disease. The rate of no-shows was also lower, indicating that the patients seen in general neurological consultations must value this level of care.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Matías-Guiu JA, García-Azorín D, García-Ramos R, Basoco E, Elvira C, Matías-Guiu J. Estudio de la asistencia neurológica ambulatoria en la Comunidad de Madrid: impacto del modelo de libre elección de hospital. Neurología. 2015;30:479–487.