In recent years, telestroke programmes have been established as a fundamental tool for extending acute stroke care to hospitals that lack an on-call neurology service. The main objective of this study is to describe the existence and functioning of the different telestroke systems and networks (TS) in Spain.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study to analyse the current situation of TS in Spain using a structured survey distributed among the members of the Stroke Study Group of the Spanish Society of Neurology.

ResultsResponses were received from 12 of the 17 Spanish autonomous communities, of which 10 had implemented TS. In addition, a literature search revealed that 2 other systems were in operation. Twelve of the 17 regions in the country have TS, achieving coverage of at least 20% of the Spanish population. Of these 10 TS, organisation was regional in 7, provincial in 2, and hospital-based in one. Most TS (9) included at least simple CT and angio-CT studies; 4 also included perfusion imaging. Nine TS operated with professional videoconferencing equipment. However, the suboptimal quality of examination via videoconferencing scan was the main problem identified in 50% of TS. Other problems detected are difficulty obtaining data from registries and the transfer of images between hospitals.

ConclusionIn recent years, a significant expansion of telestroke programmes has taken place in Spain, which has improved the accessibility of specialised care in patients with symptoms of acute stroke. This study allows us to describe the different types of TS in Spain and to detect areas for improvement and expansion, and could contribute to defining regional telestroke implementation strategies to offer quality care to the whole population.

En los últimos años se ha establecido el uso del Teleictus como una herramienta fundamental para extender la atención a los pacientes con ictus agudo hasta hospitales que no disponen de neurólogos de guardia. El objetivo principal de este trabajo es describir la existencia y funcionamiento de los distintos sistemas y redes de Teleictus (ST) en España.

MétodoEstudio transversal de la situación actual del Teleictus en España mediante la realización de una encuesta estructurada dirigida a los miembros del Grupo de Estudio de Enfermedades Cerebrovasculares de la Sociedad Española de Neurología.

ResultadosHan respondido a la encuesta desde 12 de las 17 Comunidades Autónomas (CCAA), de las cuales 10 tenían ST. Además, en la búsqueda bibliográfica se han encontrado otros 2 sistemas funcionando. 12 de las 17 CCAA de España disponen de ST, consiguiendo una cobertura de al menos el 20% de la población española. De estos 10 ST, 7 tienen una organización regional, dos provinciales y otro hospitalario. En la mayoría de los ST (9) se realizan al menos TAC simple y AngioTc, y en 4 ST también imagen de perfusión. 9 ST funcionan con equipos de videoconferencia profesionales. Sin embargo, la calidad subóptima de la exploración por videoconferencia es el principal problema identificado en el 50% de ST. Otros problemas detectados son la dificultad en la obtención de datos de los registros y la transferencia de imágenes entre hospitales.

ConclusiónEn los últimos años, se ha observado una expansión significativa de los programas de Teleictus en España, lo que ha permitido mejorar la accesibilidad de la atención especializada en casos de síntomas de ictus agudo. Este estudio permite describir los diferentes tipos de sistemas de Teleictus en España, detectar áreas de mejora y crecimiento, y podría contribuir a definir estrategias regionales para implementar el Teleictus con el fin de ofrecer una atención de calidad a toda la población.

Stroke represents the second leading cause of death in Spain, the first in women,1 and the leading cause of acquired disability in adults, representing a significant social and healthcare burden.2

The first studies on the use of alteplase in ischaemic stroke and the relevance of its early administration were performed in the 1990s.3 Soon after, in 1999, the concept of telestroke was developed with the aim of bringing the experience of specialist teams to regions where stroke care was not available, enabling organisations to centralise specialists and populations to access them when necessary.4

The first telestroke centres in Spain fundamentally focused on establishing and consolidating this healthcare model. The first centres to implement telestroke for the remote assessment of patients included hospitals in the Balearic Islands, which delivered the first treatment in 2006,5 and the Vall d’Hebron and Vic hospitals in Barcelona, which started using the system in 2007.6 These centres demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the remote care of patients with stroke, establishing the foundations for the expansion of telestroke at the national level.

Since then, telestroke has been established as an essential tool to make diagnosis and treatment of acute stroke available in hospitals without an on-call neurologist on site. In fact, several studies have shown increased rates of treatment, with no differences in the safety or efficacy of these treatments with regard to the conventional model7; this translates into better long-term functional outcomes and mortality rates.8 Therefore, the use of telestroke is recommended with a class of recommendation I and level of evidence A in the latest guidelines for the acute management of ischaemic stroke.9 Furthermore, telestroke is included in the new action plan for stroke in Europe,10 for use in remote areas with no access to an on-site neurologist with expertise in stroke management.

In Spain, the Spanish National Health System’s stroke care strategy, approved by the Inter-regional Council in 2009, established as a key priority that every patient with stroke be afforded the same possibilities for improvement thanks to an efficient healthcare model, regardless of the place of residence or the situations surrounding the event.11 Therefore, Spain’s different autonomous communities adopted the recommendations of the National Health System in their regional plans, establishing different organisational systems that enable adaptation of the advances and novelties from clinical practice guidelines for everyday care. However, some of the differences in the mortality trends observed between autonomous communities may be related to differences in acute stroke treatment and care.12

The work of the Pre2Ictus project has enabled us to identify differences in the degrees of implementation of stroke care plans and the characteristics of stroke units and teams in Spain in 2018. Although only 44% of centres responded to the survey, the study showed that 12 of the 17 autonomous communities had telestroke systems in place, providing remote care to 65 hospitals without on-call neurologists on site.13 Since 2018, the use of telemedicine has increased in all areas, and has been increasingly accepted by professionals and patients. In this regard, a centralised regional network in Andalusia was shown to enable 93% of the population to access a healthcare system attended by vascular neurologists in less than 30 minutes, with 100% accessing the system within 60 minutes, from any point in the region14; alternative models have been developed in other Spanish regions.15–18

For this reason, the aim of this study is to describe the current state of telestroke implementation, the available resources, and the different protocols in Spain.

MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional study of the current situation of telestroke in Spain using a structured survey aimed at the members of the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Stroke Study Group (Estudio de la Situación Actual en España del Teleictus desde Andalucía [SAETA]).

The survey was designed as an online questionnaire including 30 items with multiple answers, single answers, and free answers, divided into different sections: 1) general situation, organisation, and operation of the telestroke programmes (n = 10); 2) technological resources and frequent problems (n = 6); 3) healthcare outcomes (n = 10); and 4) knowledge quality and management (n = 4).

Once designed, the questionnaire was reviewed and approved by 2 international experts in neurovascular disease. The administrative offices of the Spanish Society of Neurology sent the survey to the members of the Stroke Study Group in an invitation e-mail that explained the aim of the survey and requested that responses be submitted by one professional per organisation system, to avoid duplicate responses. Participation and completion of the survey were voluntary.

For the statistical analysis of the sample, answers were grouped per autonomous community, with the aim of performing a descriptive study with reliable outcomes, without statistically analysing data to identify significant differences. Items with closed-ended answers were analysed using absolute and relative frequencies, or by calculating the mean and standard deviation, depending on the type of variable (qualitative or quantitative). Free answers were analysed with the aim of detecting areas of complementarity or deepening our understanding of closed-ended answers. This analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 365. After completing the study and analysis, we informed interested participants about the outcomes.

The study was approved by the regional ethics committee, Portal de Ética de la Investigación Biomédica de Andalucía (protocol number: 1818-N-19).

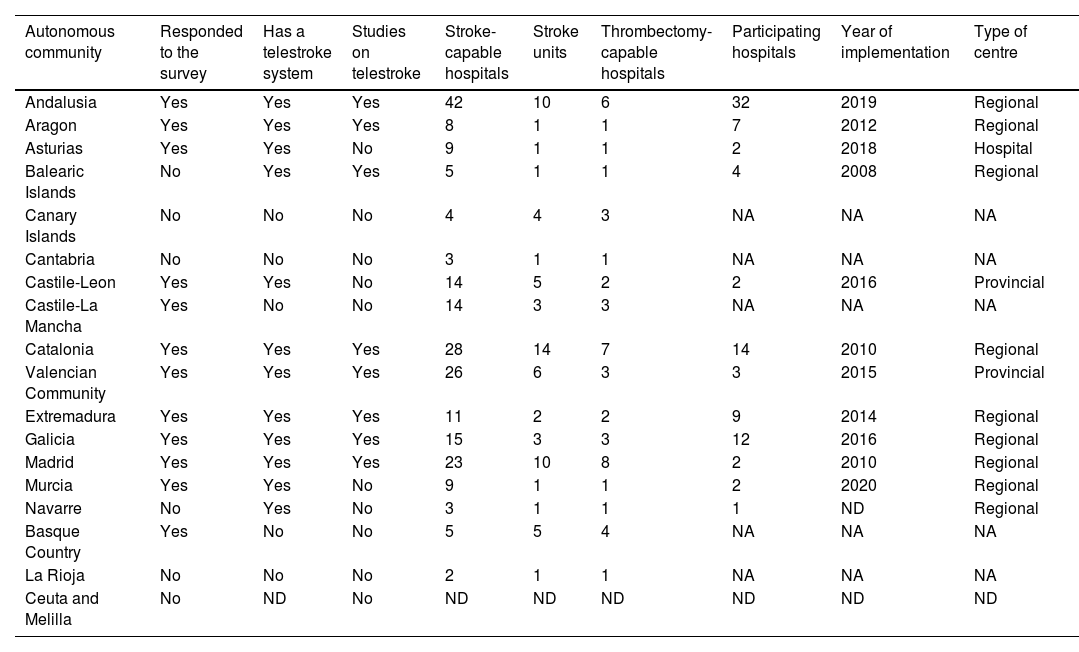

ResultsThe survey was conducted between January and June 2022. We obtained responses from 35 different hospitals, located in a total of 12 of Spain’s 17 autonomous communities, of which 10 (83%) had already implemented a telestroke programme. The number of responses per autonomous community ranged from one to 5. In addition to the 12 autonomous communities that responded to the survey, we found another 2 telestroke programmes in the Balearic Islands and Navarre in our literature search; therefore, a total of 14 Spanish autonomous communities have a telestroke system. The autonomous communities without telestroke programmes are the Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile-La Mancha, the Basque Country, and La Rioja. We obtained no response nor found data in the literature from the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla.

The different telestroke programmes started from 2010 (Catalonia and Madrid) and 2020 (Murcia), although the eldest was implemented in 2008 in the Balearic Islands (Table 1).

Description of the different telestroke programmes in Spain.

| Autonomous community | Responded to the survey | Has a telestroke system | Studies on telestroke | Stroke-capable hospitals | Stroke units | Thrombectomy-capable hospitals | Participating hospitals | Year of implementation | Type of centre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | Yes | Yes | Yes | 42 | 10 | 6 | 32 | 2019 | Regional |

| Aragon | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2012 | Regional |

| Asturias | Yes | Yes | No | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2018 | Hospital |

| Balearic Islands | No | Yes | Yes | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2008 | Regional |

| Canary Islands | No | No | No | 4 | 4 | 3 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cantabria | No | No | No | 3 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| Castile-Leon | Yes | Yes | No | 14 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2016 | Provincial |

| Castile-La Mancha | Yes | No | No | 14 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA |

| Catalonia | Yes | Yes | Yes | 28 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 2010 | Regional |

| Valencian Community | Yes | Yes | Yes | 26 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2015 | Provincial |

| Extremadura | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 2014 | Regional |

| Galicia | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 2016 | Regional |

| Madrid | Yes | Yes | Yes | 23 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 2010 | Regional |

| Murcia | Yes | Yes | No | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2020 | Regional |

| Navarre | No | Yes | No | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ND | Regional |

| Basque Country | Yes | No | No | 5 | 5 | 4 | NA | NA | NA |

| La Rioja | No | No | No | 2 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ceuta and Melilla | No | ND | No | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

NA: not applicable; ND: no data available.

According to the data obtained, a total of 221 hospitals have the capacity to treat acute stroke, with 90 of these using telemedicine systems and covering a total population of 10 043 870 inhabitants, which represents 22% of the total Spanish population.

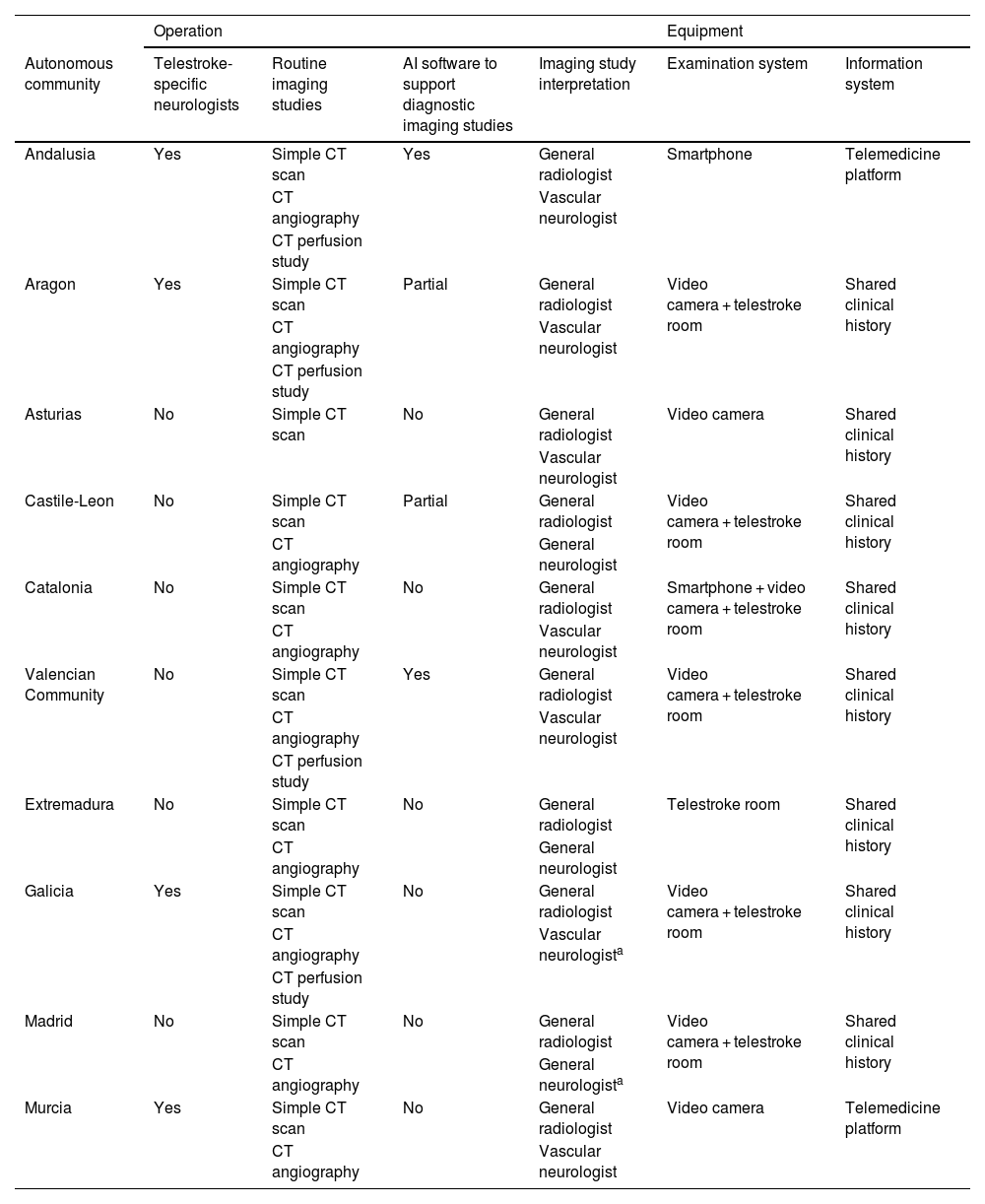

Organisation and operation of telestroke programmesOf the 10 telestroke programmes described in the survey, 7 are organised at the regional level, 2 at the provincial level, and one at the hospital level. Of the programmes operating at the regional level, 60% include neurologists working specifically in telestroke; in the remaining hospitals, this activity is the responsibility of the on-call general neurology service (Table 2).

Operation and technological equipment.

| Operation | Equipment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous community | Telestroke-specific neurologists | Routine imaging studies | AI software to support diagnostic imaging studies | Imaging study interpretation | Examination system | Information system |

| Andalusia | Yes | Simple CT scan | Yes | General radiologist | Smartphone | Telemedicine platform |

| CT angiography | Vascular neurologist | |||||

| CT perfusion study | ||||||

| Aragon | Yes | Simple CT scan | Partial | General radiologist | Video camera + telestroke room | Shared clinical history |

| CT angiography | Vascular neurologist | |||||

| CT perfusion study | ||||||

| Asturias | No | Simple CT scan | No | General radiologist | Video camera | Shared clinical history |

| Vascular neurologist | ||||||

| Castile-Leon | No | Simple CT scan | Partial | General radiologist | Video camera + telestroke room | Shared clinical history |

| CT angiography | General neurologist | |||||

| Catalonia | No | Simple CT scan | No | General radiologist | Smartphone + video camera + telestroke room | Shared clinical history |

| CT angiography | Vascular neurologist | |||||

| Valencian Community | No | Simple CT scan | Yes | General radiologist | Video camera + telestroke room | Shared clinical history |

| CT angiography | Vascular neurologist | |||||

| CT perfusion study | ||||||

| Extremadura | No | Simple CT scan | No | General radiologist | Telestroke room | Shared clinical history |

| CT angiography | General neurologist | |||||

| Galicia | Yes | Simple CT scan | No | General radiologist | Video camera + telestroke room | Shared clinical history |

| CT angiography | Vascular neurologista | |||||

| CT perfusion study | ||||||

| Madrid | No | Simple CT scan | No | General radiologist | Video camera + telestroke room | Shared clinical history |

| CT angiography | General neurologista | |||||

| Murcia | Yes | Simple CT scan | No | General radiologist | Video camera | Telemedicine platform |

| CT angiography | Vascular neurologist | |||||

AI: artificial intelligence; CT: computed tomography.

Regarding imaging studies, 6 programmes include simple CT scans and CT angiography; 3 programmes also include perfusion studies (Andalusia, Aragon, and the Valencian Community). One programme includes simple CT scans only (Asturias) and none performs routine MRI studies. In some exceptional cases, MRI studies may be performed in the hospital of origin to enable informed decision-making. In all cases, these imaging studies are interpreted by general radiologists and neurologists: general neurologists in 30% of cases (Castile-Leon, Extremadura, and Madrid), and vascular neurologists in 70%. Furthermore, 2 systems have artificial intelligence software (the e-Stroke® software by Brainomix Limited, and the RapidAI® software by iSchemaView, Inc.) to support the assessment of neuroimaging studies. One of these covered the whole population (Andalusia) and 3 covered part of the population (Aragon, Castile-Leon, and the Valencian Community).

Technological resources and frequent problemsThe technology used to perform the neurological examination and the application of the NIHSS scale varied between the different autonomous communities (Table 2). The majority of programmes (Aragon, Castile-Leon, the Valencian Community, Madrid, and Catalonia) reported using a system comprising video cameras and a telemedicine room. Some also used smartphones. In Extremadura, only a telemedicine room is used, whereas in Asturias, Galicia, and Murcia, only video cameras are used. Furthermore, in Andalusia, only smartphones are used for remote examination. It is important to highlight that examination is not performed exclusively by telephone in any of the autonomous communities; these systems are used only in cases of connection issues.

For the recording of cases in the information systems, 80% of autonomous communities use a shared medical history, and the remaining 20% (Andalusia and Murcia) have a specific telemedicine platform.

In general, IT problems were reported in almost all of the programmes assessed (except for Murcia and the Valencian Community), as well as video-conferencing or audio issues. However, these problems had already been solved in some programmes, such as in Catalonia and Galicia. In Catalonia, there had been problems viewing images and uploading studies, but these had already been solved. Furthermore, problems related to the lack of protocols and training at the hospitals of origin were reported in 2 programmes (Castile-Leon and Madrid).

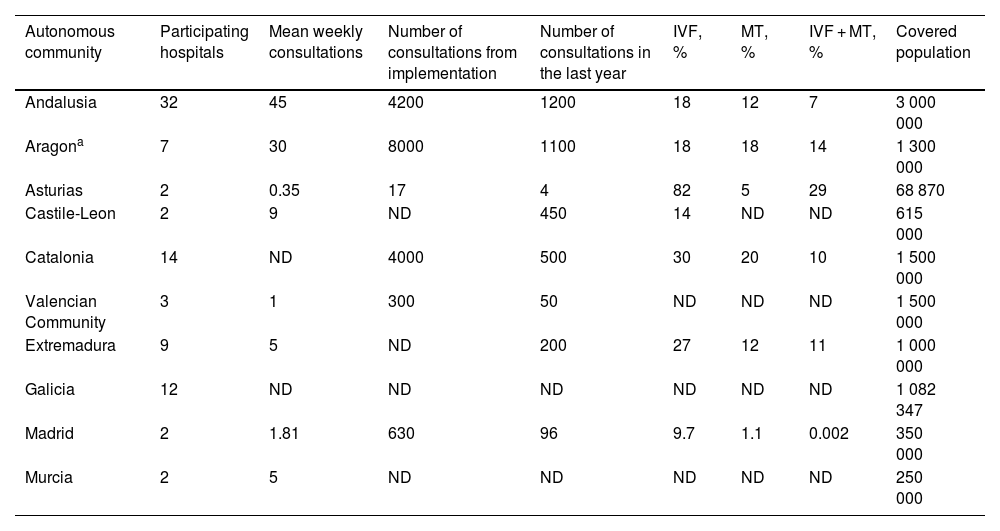

Healthcare outcomesThe survey included questions about care times, healthcare activities, and the treatments administered. This was the section with the least answers, given the difficulty of obtaining healthcare data in some systems (Table 3).

Healthcare outcomes.

| Autonomous community | Participating hospitals | Mean weekly consultations | Number of consultations from implementation | Number of consultations in the last year | IVF, % | MT, % | IVF + MT, % | Covered population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 32 | 45 | 4200 | 1200 | 18 | 12 | 7 | 3 000 000 |

| Aragona | 7 | 30 | 8000 | 1100 | 18 | 18 | 14 | 1 300 000 |

| Asturias | 2 | 0.35 | 17 | 4 | 82 | 5 | 29 | 68 870 |

| Castile-Leon | 2 | 9 | ND | 450 | 14 | ND | ND | 615 000 |

| Catalonia | 14 | ND | 4000 | 500 | 30 | 20 | 10 | 1 500 000 |

| Valencian Community | 3 | 1 | 300 | 50 | ND | ND | ND | 1 500 000 |

| Extremadura | 9 | 5 | ND | 200 | 27 | 12 | 11 | 1 000 000 |

| Galicia | 12 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 082 347 |

| Madrid | 2 | 1.81 | 630 | 96 | 9.7 | 1.1 | 0.002 | 350 000 |

| Murcia | 2 | 5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 250 000 |

IVF: intravenous fibrinolysis; MT: mechanical thrombectomy; ND: not described.

The mean number of consultations per week ranged from 0.35 in the programmes with the least hospitals included to 45 in the programmes with the most, with a median of 5 weekly consultations. The number of consultations since the systems were launched also presented great variability, ranging from 17 to 8000 with a median of 2315, as does the number of consultations in the last year, ranging from 4 to 1200 with a median of 325. Asturias reported very few connections, as the region uses a mothership model for severe strokes or strokes of undetermined time of onset.

Treatment rates also varied between systems. Fibrinolysis was administered in 9.7% to 82% of patients, endovascular treatment in 1.1% to 20%, and fibrinolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy in 0.002% to 29%.

Knowledge quality and managementAnother important question in telestroke systems is the measurement of knowledge quality and management. Six programmes have their own usable databases (Andalusia, Aragon, Catalonia, Extremadura, Galicia, and Madrid). Healthcare audits help in achieving the established aims. However, 50% of the programmes do not undergo periodic audits. In Andalusia and Extremadura, audits are performed every 6 months, and yearly in Aragon and Murcia. Audits are also performed in Catalonia, but with an undetermined frequency.

Regarding knowledge management, 90% of telestroke programmes have been reported, at least in presentations at conferences. Finally, an essential pillar is education and training in the consulting centres, which was provided in all systems at implementation and is periodically held in 40% of systems (Andalusia, Aragon, Madrid, and Murcia).

DiscussionThis study has enabled us to describe the functioning of telestroke systems in Spain. Although not all autonomous communities have responded, we observed considerable differences in the different aspects analysed in our survey.

We described and analysed different variables influencing telestroke quality and outcomes, which must be monitored to maintain optimal performance and ensure that patients receive the best treatment available. These variables include: organisational models, costs, process audits, outcomes and safety, satisfaction of patients and system users, use of information technologies, training, and documentation.19 Given the complexity of these systems, implementation guidelines20 and European recommendations have been developed to help in disseminating telestroke systems in the region,21 in which the use of larger telestroke networks for the treatment of stroke is still limited,22 with clear differences between countries, such as France, Italy, or Germany.23–25 These European recommendations include advice on the organisation of networks and the characteristics of hospitals, technical and equipment aspects, quality improvement, and data analysis.21

All programmes participating in the survey comply with the European recommendations for hospitals performing telestroke-guided treatment,21 despite differences in the organisation of systems. We may identify 3 types of organisation in the Spanish telestroke programmes: regional systems (such networks as those used in Catalonia, Galicia, and Andalusia14–16); provincial systems (such as those in Castile-Leon and the Valencian Community); or hospital systems (such as the one in Asturias, run by the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias). In one case, Aragon, a regional system is used that also includes the medical emergency services (061 or fire-fighters), who perform a triage to determine the destination of patients with acute stroke symptoms, thus covering the whole population of the autonomous community.18

Regarding the section on technical equipment, almost all autonomous communities met the European recommendations, although video-conferencing and image transfer were the main issues identified in the different programmes. In this regard, Andalusia was the only autonomous community lacking at least one remotely controlled video camera system, although published studies found no differences in assessment with the NIHSS scale using smartphones.26 This problem, which was common to all telestroke programmes would represent an overall area for improvement; for instance, the development of a reliable videoconferencing platform, ensuring a minimum level of 4G network coverage in hospital emergency departments, or the availability of a contingency plan in the event of failure of the main system used.

Regarding the diagnosis section, all programmes met the minimum criteria established, such as the 24/7 availability of simple CT studies. The assessment of imaging studies in telestroke networks is a controversial subject, although the literature reports strong interobserver concordance in the assessment of imaging studies for the treatment of acute stroke among expert neurologists and neuroradiologists.27,28 In the telestroke programmes analysed, imaging studies are assessed by radiologists at the hospitals of origin and neurologists working in the telestroke programme, although there are some exceptions in which the study is first interpreted by vascular neurologists, in centres without 24-h availability of on-call radiologists.

There was a generalised lack of data in the section about knowledge quality and management, as only 3 programmes provided complete data, including management times: Catalonia, Madrid, and Andalusia. Some regions automatically collect healthcare provision data in their different healthcare platforms, but these are only accessible upon request from the health authorities of each autonomous community. Due to the very limited representation of the sample, these data were not included in the analysis, which represents a significant limitation of our study. This difficulty of accessing healthcare data make audits and analysis of areas for improvement a challenge; these processes are performed in 50% of the participating programmes. To maintain healthcare quality, it is necessary to establish protocols and hold training sessions at the consulting centres, at least at the beginning of the system operation. Despite all this, the results from this last section diverge from the European recommendations,21 in which the creation of specific protocols, periodic training (at least twice a year), and the analysis of healthcare data play an essential role in improving stroke care quality; therefore, this may represent an area for further work and improvement in the future for the different groups.

To our knowledge, this is the first national survey on the functioning of telestroke in Spain. This article reflects a significant effort by the autonomous communities to meet the objectives of the Spanish National Health System’s stroke care strategy by implementing these telemedicine systems. However, despite this effort, the proposed objectives have not been reached. The advances made thanks to the autonomous communities, scientific societies, and professionals working in the code stroke healthcare network have enabled expansion of the existing coverage to rural areas with more difficulties in accessing treatment for acute stroke. In only 4 years, the number of hospitals providing telemedicine services has increased by 30. This increase means that a total of 90 hospitals provide care to patients with acute stroke through telestroke programmes, covering 22% of the Spanish population (Fig. 1). However, there are areas where this care is not available, most frequently due to the short distance from the different towns to a tertiary hospital with a stroke unit; therefore, a programme of this type was considered unnecessary. In the case of larger regions where the distance between towns and a stroke unit is more than 45 minutes, an analysis of accessibility may be considered, such as the ones performed in other autonomous communities14 to assess implementation needs and the most suitable type of system for each population.

Telestroke is a constantly progressing field, in which new lines of research arise to improve the care of patients with stroke. One of the most novel lines of research that is currently being consolidated is the implementation of new technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, with the aim of increasing diagnostic accuracy and optimising treatments. Another possible line of research would consist of exploring the impact of training and qualification of healthcare professionals on remote care quality, which may help in identifying good practices and efficient protocols. Regarding logistics and transfers, the strategies enabling optimal coordination between different healthcare levels may be assessed, in order to minimise response times and the resources used, therefore improving clinical outcomes. Finally, health economics studies in the context of telestroke may provide valuable information on cost-effectiveness and efficiency in the allocation of resources, supporting those responsible for decision-making in the implementation and expansion of these programmes.

Our study presents the limitations described above. The main limitation is the lack of information from all autonomous communities, as we received no responses from the Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Navarre, La Rioja, or the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla. Furthermore, we found no data in the literature on the latter 2 cities. Another limitation of our study, described shortly before, is the lack of access to data on healthcare quality, which are difficult to extract from the digital clinical history without the extra effort of providing information to an external database other than the patient clinical record. This hinders the identification of areas for improvement, such as shortening management times, improving diagnosis, or identifying centres requiring adaptation of protocols. Despite these limitations, this study represents a first approach to the different telestroke programmes in Spain, and has enabled us to identify areas for improvement to work on in the future.

ConclusionsThe past few years have witnessed a significant expansion of telestroke programmes in Spain, improving the population’s access to expert neurologists in the event of acute stroke symptoms.

Surveys like this one enable us to describe different types of systems in Spain as well as the differences between them, and may be useful for detecting areas for improvement and further development, such as, for example, the systematic recording of the activity performed.

Similar studies may be used to define the different regional strategies to implement a tool like telestroke, with class I recommendation and level of evidence A, and provide quality care to the whole population, thus achieving the objectives set out in the action plan for stroke in Europe 2018 to 2030.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, private, or non-profit organisation.

We would like to express our particular gratitude to all the responding participants.