Depression affect individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) more frequently compared with the general population. It can worsen the symptoms of MS, influence disability progression, and significantly reduce the quality of life (QoL).

MethodWe investigated the prevalence of depressive symptoms in a cohort of 200 patients with MS (76% women) and their association with sleep patterns, fatigue, QoL, demographics, and other clinical characteristics in real-world settings. The study was conducted through clinical evaluations and questionnaires related to depression: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS); fatigue: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; sleep quality: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Epworth Sleepiness Scale; and QoL: Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQOL-54).

ResultsAccording to the BDI and HDRS, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 40.5 and 28.27%, respectively. Patients with depressive symptoms exhibited higher disability scores, longer ambulation times, worse cognitive function in the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, and poorer sleep quality. They also had significantly higher fatigue and daytime somnolence scores, as well as lower scores on the MSQOL-54: physical (40.55 vs. 62.3; P<.001) and mental (44.49 vs. 71.89; P<.001) health composites. We demonstrated the correlation between depression and fatigue, as well as their negative impact on QoL in patients with MS.

ConclusionThis study underscores the prevalence and impact of depression in MS, emphasizing the importance of routine screening and active management of psychiatric comorbidities in individuals with MS. These findings contribute valuable insights into the complex interplay between mental health, disease variables, and QoL in MS.

La depresión afecta a los individuos con esclerosis múltiple (EM) con mayor frecuencia en comparación con la población general. Puede agravar los síntomas de la EM, influir en la progresión de la discapacidad y reducir significativamente la calidad de vida (QoL).

MétodoInvestigamos la prevalencia de los síntomas depresivos en una cohorte de 200 pacientes con EM (76% mujeres) y su asociación con los patrones de sueño, fatiga, QoL, características demográficas y otras características clínicas. El estudio se llevó a cabo a través de evaluaciones clínicas y cuestionarios relacionados con la depresión: Inventario de Depresión de Beck (BDI) y Escala de Depresión de Hamilton (HDRS); fatiga: Escala de Impacto de Fatiga Modificada (MFIS); calidad del sueño: Índice de Calidad del Sueño de Pittsburgh (PSQI) y Escala de Somnolencia de Epworth (ESS); y QoL: Cuestionario de Calidad de Vida en Esclerosis Múltiple-54 (MSQOL-54).

ResultadosSegún el BDI y la HDRS, la prevalencia de síntomas depresivos fue del 40,5% y del 28,27%, respectivamente. Los pacientes con síntomas depresivos mostraron puntuaciones de discapacidad más altas, tiempos de ambulación más largos, peor función cognitiva en la SDMT y una peor calidad del sueño. También presentaron puntuaciones significativamente más altas de fatiga y somnolencia diurna, así como puntuaciones más bajas en el MSQOL-54: componentes de salud física (40,55 vs. 62,3; p&#¿;<&#¿;0,001) y mental (44,49 vs. 71,89; p&#¿;<&#¿;0,001). Demostramos la correlación entre la depresión y la fatiga, así como su impacto negativo en la QoL en pacientes con EM.

ConclusiónEste estudio subraya la prevalencia e impacto de la depresión en la EM, enfatizando la importancia del cribado rutinario y la gestión activa de las comorbilidades psiquiátricas en individuos con EM. Estos hallazgos aportan valiosas ideas sobre la compleja interacción entre la salud mental, las variables de la enfermedad y la QoL en la EM.

The prevalence of depression is higher in patients with multiple sclerosis (pwMS) than in the general population or those with other neurological and chronic conditions, and the lifetime risk of developing a major depressive disorder in pwMS can be greater than 50%.1–4 This close association could be explained for several factors: psychological reactions to an unpredictable and potentially disabling disease; structural damage in specific areas of the brain; inflammation-related changes; imbalance of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; genetic factors; and common psychosocial risk factors.5–10

The relevance of studying depression in MS stem from the fact that depression could be associated with disability progression,11,12 delay in the diagnosis of MS,13 decreased health-related quality of life (QoL),14,15 compromised cognitive functions,16 increased risk of death by suicide,17 higher use of healthcare resources,18 affected decisions to initiate disease-modifying therapies (DMTs),19 and poor adherence to DMT.20,21

The association between depression, and MS-associated symptoms, such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive dysfunction,10,22–24 suggests that while investigating depression in MS, all these conditions need to be evaluated collectively.

In this study, we aimed to examine the prevalence of depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbances in a cohort of individuals with MS. We also explored the relationship between these factors and clinical and demographic variables, and assessed their impact on QoL of pwMS.

Materials and methodsStudy design and participantsThis was a retrospective, cross-sectional, multicenter clinical study. The participants were recruited from a cohort of pwMS ≥18&#¿;years of age and with a definite diagnosis of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), secondary-progressive, or primary-progressive MS according to the McDonald criteria,25 who attended consultations at two Spanish MS clinics. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association, approved by the local ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All patients, besides their clinical evaluation, performed a Timed 25-Foot Walk Test (T25FW),26 a 9-Hole Peg Test (9HPT),26 a Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT),27 and completed the following questionnaires: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS),28 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),29 Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS),30 Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQOL-54),31 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS),32 and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)33 as part of standardized evaluation.

Qualification criteriaConsecutive patients who visited the hospitals between January 2021 and December 2022 were offered the opportunity to participate in this study. The exclusion criteria were age <18&#¿;years, insufficient Spanish language proficiency, patients who were unable to correctly complete the clinical scales, and those who did not have Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) or relapse data for at least 1&#¿;year previously. The first 200 patients who consecutively attended and met the inclusion criteria with none of the exclusion criteria, and agreed to participate in the study, were selected.

Evaluation of patient characteristicsDemographic and disease-related factors were retrieved from patient record files. Neurological disability was measured using the EDSS.34 Functional status was evaluated using the T25FW and 9-HPT, while cognitive function was evaluated using oral SDMT. To evaluate depression symptoms, data were obtained from the HDRS and BDI. Data from the MFIS, PSQI, ESS and MSQOL-54 were also obtained.

The MFIS yields 4 scores related to the patient's total, physical, psychosocial, and cognitive fatigue in the month prior to the assessment. It categorizes patients as having significant fatigue when total MFIS score is ≥38.28

The PSQI29 yields a score indicative of sleep quality. Patients were classified as follows: <5 points, no sleep problems; 5–7 points, need for medical attention; 8–14 points, need for medical attention and treatment for sleep problems; and >14 points, severe sleep problems.

ESS30 assesses the degree of sleepiness in different situations. A score >10 indicated an abnormal level of daytime sleepiness.35

The MSQOL-5431 is a multidimensional questionnaire comprising 54 items, which allows for obtaining scores in several dimensions that are finally combined to form 2 composite scores: a MSQOL-54 physical health composite score (MSQOL-54phcs) and a MSQOL-54 Mental Health composite score (MSQOL-54mhcs). The composite scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a better QoL.

The BDI consists of 21 items and yields a total score indicative of the severity of depressive symptoms. It classifies patients as follows: 0–13 points, no or minimal depression; 14–19 points, mild depression; 20–28 points, moderate depression; and >28 points, severe depression.33,36

The HDRS32 evaluates the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. It classifies patients as follows37: a score <10, absence of depression; 10–13 points, mild depression; 14–17 points, mild-to-moderate depression; and 18–51 points, moderate-to-severe depression.

When the obtained BDI and HDRS scores indicated severe depressive symptoms, or if the neurologist suspected the existence of severe depression, the patient was referred to an experienced psychiatrist in MS (A–C, E) who, through a structured clinical interview and in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria,38 classified the patients into no depression/other non-depressive psychiatric disorders, mild, moderate, or severe depression, and determined the need for treatment.

Statistical analysesBaseline characteristics were reported as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequency for categorical variables and the mean±standard deviation (SD), or median, minimum, maximum. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Chi-squared test, Student's t-test, or the Mann–Whitney U test. Associations between categorical variables were described using the relative risk (RR) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For the analysis of the relationship between quantitative variables, the Pearson or Spearman's correlation coefficient was applied depending on the nature of the data (r) and interpreted according to: <0.10 indicating negligible association, 0.10–0.29 low association, 0.30–0.49 moderate association, and ≥0.50 high association.

Multivariate predictive linear regression models were performed using scores on depression and anxiety measures as dependent variables, and scores on variables showing significant associations in bivariate analysis as predictors.

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS software (version 27.0; Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsStudy populationTable 1 presents the demographic and disease-related characteristics of the patients. The mean age of the 200 included patients was 44.2±10.3&#¿;years and 76% (n=152) were women (Table 1). HDRS data were missing for 9 patients.

Baseline characteristics of study participants.

| Patient characteristics | n | Mean/median | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (women/men) | 152/48 | ||||

| Type of MS (RRMS/SPMS/PPMS) | 181/13/6 | ||||

| Age (years) | 200 | 44.22/45 | 10.3 | 20 | 67 |

| EDSS | 200 | 2.06/1.5 | 1.8 | 0 | 7.5 |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 200 | 10.52/9.8 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 38.9 |

| Number of previous relapses | 200 | 3.68/3 | 2.4 | 1 | 15 |

| Time since last relapse (years) | 200 | 5.24/4 | 4.3 | 0 | 23 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 170 | 24.96/24 | 4.5 | 18 | 43.7 |

| Physical comorbid disease (%) | 97 (48.5) | ||||

| Psychiatric history (%) | 22 (11) | ||||

| Antidepressant medication (%) | 62 (31) | ||||

| T25FW | 191 | 6.02/5.23 | 2.64 | 3 | 19.47 |

| SDMT | 193 | 45.75/46 | 12.32 | 10 | 75 |

| Dominant 9HPT | 194 | 23.33/21.23 | 8.14 | 14.1 | 73.81 |

| Non dominant 9HPT | 194 | 24.73/22.13 | 8.76 | 14 | 65.18 |

MS: multiple sclerosis; RRMS, recurrent–remittent MS; SPMS: secondary progressive MS; PPMS: primary progressive MS; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; BMI: body mass index; T25FW: Timed 25-Foot Walk; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; 9HPT: 9-Hole Peg Test; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2 presents the means and SD for depression, fatigue, QoL, and sleep disorders according to the questionnaires and scales used.

Means and standard deviations of anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep disorders according to the questionaries and scales used.

| Questionnaire | n | Mean | SD | Min | Max | % above cutoff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI | 200 | 13.04 | 10.5 | 0 | 50 | 40.5 |

| HDRS | 191 | 12.69 | 8.65 | 0 | 38 | 58.6 |

| Total MFIS | 197 | 36.8 | 22.1 | 0 | 83 | 48.2 |

| Physical MFIS | 197 | 17.98 | 10.7 | 0 | 36 | |

| Cognitive MFIS | 197 | 15.4 | 10.6 | 0 | 40 | |

| Psychosocial MFIS | 197 | 3.84 | 3.3 | 0 | 31 | |

| ESS | 197 | 7.94 | 4.7 | 0 | 22 | 34.5 |

| PSQI | 197 | 8.25 | 4.7 | 0 | 24 | 75.7 |

| MSQOL-54 physical health composite | 177 | 53.2 | 21.4 | 5.8 | 100 | |

| MSQOL-54 mental health composite | 177 | 60.76 | 21.77 | 3.3 | 95 |

SD: standard deviation; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; MSQOL-54: Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54.

The mean depression score was 13.04 (SD 10.5) according to BDI and 12.69 (SD 8.65) according to HDRS. Eighty-one patients (40.5%) had a BDI score above the cutoff (≥14), and 58.6% of the 191 who completed the HDRS had a score above the cutoff (≥10). A score indicative of severe depression was observed in 20 patients (10%) according to BDI (BDI≥29), and 54 (28.27%) obtained a score indicative of moderate-to-severe depression according to HDRS (HDRS≥18).

Nineteen patients with a BDI score indicative of severe depression and an HDRS score suggesting moderate-to-severe depression along with 5 others who were considered by their neurologist to potentially have severe depression (average BDI 26.2, average HDRS 25.4) were clinically evaluated by a psychiatrist, who confirmed depression in 16 (84.2%) of the 19 cases identified as severe depression by BDI.

Thirty-one percent of patients were receiving antidepressant treatment at the time of assessment. The proportion was significantly higher among those with greater disability (EDSS >2) (P=.016), as well as those experiencing depressive symptoms (BDI and HARS) (P<.001), fatigue (MFIS) (P<.001), and sleep disturbances (PSQI) (P=.003). However, 46.8% of patients with depression and 22.22% of those with severe depression according to BDI were not taking antidepressants at the time of the assessment.

The mean fatigue score according to total MFIS was 36.8 (SD 22.1). The proportion of patients with a total MFIS score above the cutoff value was 48.2%.

The mean ESS score was 7.94 (SD 4.7), and 34.5% of participants had a score indicative of pathological sleepiness. Meanwhile, according to PSQI, only 24.3% of participants included in the cohort lacked sleep problems, 29.95% required medical attention for a sleep problem, 32.49% required attention and treatment, and 13.7% had severe sleep problems.

Patients with depression according to the BDI had significantly higher mean EDSS scores, longer ambulation time, non-dominant upper extremity function results, lower SDMT scores, higher fatigue scores, worse sleep quality, and higher daytime sleepiness (Table 3).

Disability markers, cognitive function, fatigue, and sleep based on the presence or absence of depression according to BDI.

| BDI no depression (n=119) | BDI depression (n=81) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| EDSS | 1.78 | 1.61 | 2.48 | 1.92 | .006 |

| T25FW | 5.63 | 2.07 | 6.60 | 3.24 | .022 |

| Dominant 9HPT | 22.44 | 7.37 | 24.65 | 9.05 | .063 |

| Non dominant 9HPT | 23.54 | 7.59 | 26.51 | 10.04 | .028 |

| SDMT | 48.36 | 12.15 | 41.72 | 11.54 | <.001 |

| Total MFIS | 26.81 | 18.30 | 52.04 | 18.15 | <.001 |

| Physical MFIS | 13.58 | 9.73 | 24.53 | 8.46 | <.001 |

| Cognitive MFIS | 10.97 | 8.61 | 22.03 | 9.75 | <.001 |

| Psychosocial MFIS | 2.43 | 2.07 | 5.51 | 2.17 | <.001 |

| PSQI | 6.40 | 3.85 | 10.98 | 4.45 | <.001 |

| ESS | 7.16 | 4.26 | 9.07 | 5.10 | .006 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; T25FW: Timed 25-Foot Walk; 9HPT: 9-Hole Peg Test; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation.

Patients with progressive forms of MS had significantly higher EDSS, BDI, total, physical, and psychosocial MFIS scores; lower SDMT scores; and longer T25FW and 9HPT times than those with RRMS. No differences were observed in ESS, PSQI, HARS, or HDRS scores (Table 4).

Demographic, disability markers, depression, cognitive function, fatigue, and sleep according to type of MS.

| Variable (n RMS/n PMS) | RRMS | PMS | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) (181/19) | 43.21 | 10.21 | 53.79 | 5.9 | <.001 |

| Time since diagnosis (years) (181/19) | 10.46 | 7.16 | 11.07 | 6.1 | .585 |

| EDSS (181/19) | 1.71 | 1.36 | 5.39 | 1.79 | <.001 |

| T25FW (181/15) | 5.74 | 2.32 | 9.34 | 3.76 | <.001 |

| Dominant 9HPT (181/17) | 22.92 | 8.1 | 27.59 | 7.42 | .002 |

| Non dominant 9HPT (181/17) | 24.12 | 8.22 | 31.04 | 11.56 | .004 |

| SDMT (181/17) | 46.55 | 12.04 | 37.47 | 12.41 | .007 |

| BDI (181/19) | 12.66 | 10.52 | 16.63 | 9.81 | .046 |

| HDRS (174/17) | 12.36 | 8.54 | 16.12 | 9.24 | .096 |

| Total MFIS (181/17) | 35.81 | 22.11 | 48.12 | 19.44 | .026 |

| Physical MFIS (181/17) | 17.20 | 10.52 | 26.29 | 9.64 | .001 |

| Cognitive MFIS (181/17) | 15.32 | 10.64 | 16.41 | 10.74 | .645 |

| Psychosocial MFIS (181/17) | 3.7 | 3.33 | 5.41 | 2.39 | .006 |

| PSQI (181/19) | 8.01 | 4.52 | 10.15 | 5.01 | .075 |

| ESS (181/19) | 7.98 | 4.68 | 7.53 | 4.95 | .622 |

MS: multiple sclerosis; RRMS: recurrent–remittent MS; PMS: progressive MS; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; T25FW: Timed 25-Foot Walk; 9HPT: 9-Hole Peg Test; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; MFIS: Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; SD: standard deviation.

No differences were found in the proportion of depression according to the BDI or HDRS or in the proportion of excessive daytime somnolence, anxiety, fatigue, or poor sleep quality between men and women.

The presence of fatigue increased the RR of pathological depression by 4.51 times (95% CI: 2.77–7.35) according to the BDI and 2.36 times (95% CI: 1.77–3.14) according to the HDRS. The presence of sleep problems increased the RR of pathological depression by 3.34 times (95% CI: 1.65–6.75) according to the BDI.

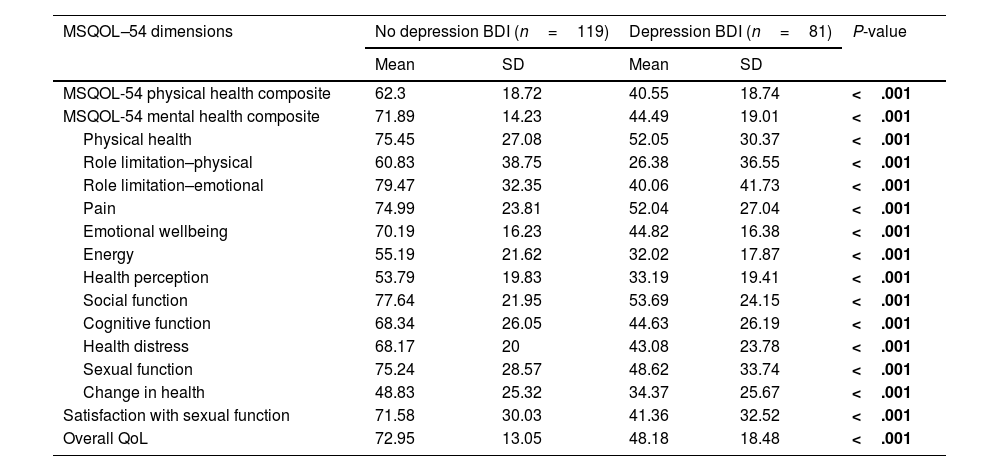

Quality of lifeThe results of the MSQOL-54 are presented in Table 2 and those of MSQOL-54 sub-scales in Table 5. The mean MSQOL-54phcs and MSQOL-54mhcs were 53.2 (SD 21.4) and 60.76 (SD 21.77), respectively. Patients with progressive forms of MS obtained significantly lower scores on the MSQOL-54phcs (32.9 vs. 55.68; P<.001) but not on the MSQOL-54mhcs (53.75 vs. 61.5; P=.115). The mean MSQOL-54phcs and MSQOL-54mhcs, and all MSQOL-54 subscales differed significantly between patients with or without depression according to the BDI (Table 6).

MSQOL-54 scores (mean and standard deviation) of the total study population and according to type of MS.

| MSQOL-54 | Mean overall | SD | Mean RRMS | Mean PMS | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSQOL-54 physical health composite | 53.2 | 21.4 | 55.68 | 32.9 | <.001 |

| MSQOL-54 mental health composite | 60.76 | 21.77 | 61.5 | 53.75 | .115 |

| MSQOL-54 sub-scales | Mean overall | SD | Mean RRMS | Mean PMS | P-value |

| Physical health | 65.9 | 30.6 | 70.14 | 28 | <.001 |

| Role limitation–physical | 46.9 | 41.4 | 50.45 | 13.2 | <.001 |

| Role limitation–emotional | 63.53 | 41.17 | 66.1 | 39.2 | .02 |

| Pain | 65.63 | 27.53 | 68 | 43.8 | .002 |

| Emotional wellbeing | 59.85 | 20.5 | 63.1 | 59.5 | .478 |

| Energy | 45.74 | 23.14 | 47.36 | 31.4 | .005 |

| Health perception | 45.39 | 22.08 | 46.95 | 31.4 | .004 |

| Social function | 67.87 | 25.68 | 70 | 48.6 | .001 |

| Cognitive function | 58.67 | 28.54 | 64.4 | 58 | .507 |

| Health distress | 57.94 | 24.86 | 59.4 | 44.7 | .022 |

| Sexual function | 64.32 | 33.4 | 66.4 | 45.8 | .026 |

| Change in health | 42.98 | 26.37 | 44.4 | 29.4 | .022 |

| Satisfaction with sexual function | 59.29 | 34.37 | 60.6 | 47 | .186 |

| Overall QoL | 62.85 | 19.69 | 63.6 | 56.3 | .076 |

MS: multiple sclerosis; RRMS: recurrent–remittent MS; PMS: progressive MS; MSQOL-54: Multiple sclerosis Quality of Life-54; SD: standard deviation.

MSQOL-54 scores in patients with or without depression according to BDI.

| MSQOL–54 dimensions | No depression BDI (n=119) | Depression BDI (n=81) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| MSQOL-54 physical health composite | 62.3 | 18.72 | 40.55 | 18.74 | <.001 |

| MSQOL-54 mental health composite | 71.89 | 14.23 | 44.49 | 19.01 | <.001 |

| Physical health | 75.45 | 27.08 | 52.05 | 30.37 | <.001 |

| Role limitation–physical | 60.83 | 38.75 | 26.38 | 36.55 | <.001 |

| Role limitation–emotional | 79.47 | 32.35 | 40.06 | 41.73 | <.001 |

| Pain | 74.99 | 23.81 | 52.04 | 27.04 | <.001 |

| Emotional wellbeing | 70.19 | 16.23 | 44.82 | 16.38 | <.001 |

| Energy | 55.19 | 21.62 | 32.02 | 17.87 | <.001 |

| Health perception | 53.79 | 19.83 | 33.19 | 19.41 | <.001 |

| Social function | 77.64 | 21.95 | 53.69 | 24.15 | <.001 |

| Cognitive function | 68.34 | 26.05 | 44.63 | 26.19 | <.001 |

| Health distress | 68.17 | 20 | 43.08 | 23.78 | <.001 |

| Sexual function | 75.24 | 28.57 | 48.62 | 33.74 | <.001 |

| Change in health | 48.83 | 25.32 | 34.37 | 25.67 | <.001 |

| Satisfaction with sexual function | 71.58 | 30.03 | 41.36 | 32.52 | <.001 |

| Overall QoL | 72.95 | 13.05 | 48.18 | 18.48 | <.001 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; MSQOL-54: Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54; SD: standard deviation.

No differences were found in the different QOL dimensions between men and women, except for the emotional well-being dimension (65.46 vs. 58.18; P=.046).

Correlation analysis-bivariate analysisA significant, strong positive correlation was observed between the HDRS and BDI (r&#¿;=&#¿;0.8; P<.001). The scores on the depression scales (BDI and HDRS) were strongly and significantly (P<.001) correlated with total MFIS (0.72 and 0.7, respectively), as well as with sleep quality (0.56 and 0.61). They were inversely and moderately correlated (P<.001) with cognitive performance (−0.33 and −0.4). BDI and HDRS showed a weak or moderate correlation (P<.001) with EDSS (0.32 and 0.31).

A strong negative correlation (P<.001) was found between the physical and mental scores of the MSQoL-54 and the BDI (r = −0.77), HDRS (r = −0.71), MFIS (r = −0.74), and PSQI (r = −0.53) scores.

Regression analyses–multivariable analysisHigher levels of fatigue, poorer sleep quality, and cognitive functioning were significant predictors of depression, as identified by the HDRS (F = 80.91; P<.001) and yielded an explained variance proportion of R2=0.58. Higher levels of fatigue and poorer sleep quality were significant predictors of depression, as identified by the BDI (F=118.80; P<.001), and yielded an explained variance proportion of R2=0.56.

DiscussionIn this study, we aimed to examine the prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms in a cohort of 200 pwMS and their relationship with sleep quality, fatigue, QoL, demographics, and other clinical characteristics relevant to MS in real-world conditions. Patient demographics were comparable to those in other studies on MS,15,39 and the questionnaires and scales used in our study have been validated and widely used in MS evaluations.40–45

The manifestations of depression in MS could be attributed to a primary depressive disorder, or the depressive symptoms could be related to the inflammatory processes inherent in MS, due to the effects of MS medications, or as an adaptive disorder with a depressed mood resulting from the patient's emotional response to MS. Distinguishing between these potential diagnoses involves high complexity and requires thorough analysis of the medical history, physical examination, clinical interview, imaging, and laboratory tests.2

Depression is the most common comorbidity in pwMS,46 although its prevalence is highly variable in the different studies reported depending on, among other factors, the number of participants, the assessment tools used, and whether a diagnosis of depressive disorder was established by a semi-structured review or the presence of depressive symptoms detected by different questionnaires.2,45 A prevalence ranging from 4.98% to 58.9% (mean 23.7%) has been estimated in a systematic review,1 and 30.5% in a recent study.47 In this study, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 40.5% according to BDI and 58.6% according to HDRS. These values are higher than those in other studies20,39 but lower than those in another Spanish study.48 Similar to other reports, our study found that the mean EDSS score was higher in patients with depressive symptoms, and that depressive symptoms were more frequent in patients with progressive forms of the disease.48 This suggests that more neurological damage implies greater disruption of neurological pathways and could support the hypothesis of a structural origin of depressive symptoms in MS. However, even in a cohort with a relatively low mean EDSS score and a low proportion of progressive forms of MS, such as ours, the proportion of depressive symptoms was high, which suggests that emotional or psychological reactions to the diagnosis cannot be excluded.

The high prevalence of depressive symptoms found in our study can be explained, at least in part, by the assessment tools used. Screening tools assess the most recent symptoms of MS and may overestimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms and many items may be influenced by MS symptoms. Therefore, it is recommended to use scales that minimally reflect physical symptoms, including the BDI.2,49 It has been suggested that pwMS were psychosocially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.50 We cannot exclude the possibility that this factor could have contributed to the high rates of depressive symptoms observed, as the assessment was conducted close to the onset of the pandemic.

Unlike in the general population, depression in MS is not more common in women,4 and no significant differences were found in the average BDI and HDRS scores or the percentage of patients with depressive symptoms according to sex in the present study.

In DSM-5, diagnostic criteria for depression include, among other conditions, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue or loss of energy, and diminished ability to think or concentrate.38 These symptoms are common in individuals with MS, making it challenging to differentiate between true depression and disease-related symptoms. Consequently, depression in MS may be obscured by fatigue, cognitive issues, and sleep disturbances, often resulting in either a delayed or missed diagnosis.51

In up to 42% of pwMS, moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms are not diagnosed,52 although an increased rate of antidepressant treatment in pwMS compared to the general population has been reported.53 In our study, even though 31% of patients were on antidepressant treatment at the time of assessment, which is higher than what has been reported by some,39 it is noteworthy that 46.75% of patients with BDI scores above the cutoff were not receiving antidepressant treatment. On the other hand, 21% of patients with severe depressive symptoms, according to BDI, were not on antidepressant treatment; this suggests that depression in MS is likely underdiagnosed and undertreated.54

Self-reporting of depressive symptoms may be influenced by the presence of fatigue or sleep disturbances, which are highly prevalent in pwMS. Therefore, the detection of depressive symptoms using these scales should not be interpreted as a direct indicator of depression. Those patients, identified as having severe depression by the scales or their neurologists, were re-evaluated by a psychiatrist, and 16% of them did not meet the criteria for clinical depression. Thus, while the HDRS and BDI accurately identified 84% of patients with depressive symptoms, only 47% of those diagnosed with moderate-to-severe symptoms of depression were validated by a psychiatrist. Therefore, we conclude that while the BDI and HDRS are useful screening tools for detecting symptoms of depressive disorders, they are not suitable for diagnosing severe depression.

Fatigue is one of the most frequent symptoms associated with MS and affects 35%–97% of pwMS.10,23,39,42 Prevalence of cognitive impairment in adults with MS ranges from 34% to 65%,55 and sleep problems affect up to 68% of patients.24,35 In our study, 48.2% of pwMS experienced fatigue, 34.5% severe daytime somnolence, and 75.7% sleep problems. Therefore, the coexistence of depression with fatigue, cognitive impairment, and/or sleep disturbance is common in pwMS. In our study, 31.97% of patients were diagnosed to have fatigue and depression concurrently according to MFIS and BDI criteria, with over 80% of patients having BDI scores above the cutoff value also have MFIS scores indicative of pathological fatigue. These findings demonstrate a strong correlation between fatigue and depression, which is greater than that reported in other studies that found strong56 or moderate correlations.28,48 The strongest indicator of increased fatigue, according to reports, is an increase in BDI scores,57 and fatigue is unlikely to resolve while depression is present.58 The close relationship between fatigue and depression could indicate a common pathogenic mechanism of both conditions (proinflammatory cytokines, microglial activation, impairment of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, and neurodegeneration, among others)10 or the existence of other causes that could contribute to both conditions, such as sleep disturbances, pain, emotional stress, medications, and other comorbidities.59 Patients with higher disability scores also scored higher for depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance. This observation suggests that a severe disruption of neural pathways can lead to a myriad of symptoms beyond physical disability.

The presence of fatigue in individuals with MS should serve as a warning to clinicians to consider the possibility of depression.60 In our study, both fatigue and sleep disturbance significantly increased the risk of depression. Not only is depression directly associated with fatigue in MS, but it also indirectly influences HRQoL dimensions; antidepression therapy can improve fatigue61 as well as HRQoL. Therefore, it is essential to simultaneously assess depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbances in pwMS to initiate specific symptomatic treatments. This is crucial because, both individually and interindividually, these conditions negatively impact QoL.39,42,61

Poor sleep quality and excessive daytime somnolence are more common in pwMS than in the general population, with a previously reported range of prevalence of poor sleep quality being 48%–68%.24,35,62 The largest study on excessive daytime sleepiness in MS, in more than 2300 patients, found a prevalence of 30%.63 In our study, an even higher prevalence of poor sleep quality (75.7%) and daytime somnolence (34.5%) was found. Additionally, we demonstrated a significant correlation between sleep quality and depression, anxiety, and HRQoL, as previously described.35

pwMS generally have a lower HRQoL compared to the general population and individuals with other chronic conditions.64–66 In our study, the mean MSQOL-54phcs was similar to the scores reported in a limited sample of Spanish patients in a study involving several European countries67 and was lower than those in most other reports.40,68,69 The significant association of HRQoL with depression, sleep quality, and fatigue, and to a lesser extent, with disability, could also explain the differences between the studies. In our sample, despite the low disability (mean EDSS=2), the MSQOLphcs could be considered low, suggesting that perhaps EDSS does not accurately reflect self-perceived disability or that other factors such as fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbances directly or indirectly influence QoL, as observed in the regression analysis. Therefore, we contemplate that when HRQoL is studied in MS, these factors should be added to the sociodemographic and disability variables. Studies on the QoL in pwMS considering fatigue or depression are scarce, and the rates of depression found were lower than those observed in our study.40,42 The higher prevalence of depression in our sample may explain lower HRQoL. Few studies have examined the influence of poor sleep quality on HRQoL in pwMS, except for one study that indicated a strong correlation between poor sleep quality and worse HRQoL.35 The high proportion of poor sleep quality found in our cohort could also explain the lower HRQoL than that in other studies, despite a relatively low level of disability.

In summary, this cross-sectional study revealed a substantial burden of depressive symptoms among pwMS. Many patients with depressive symptoms do not receive appropriate and timely treatment, highlighting the potential underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression in the MS population. Notably, this study also identified a significant correlation between depression and factors such as fatigue, sleep disturbances. Fatigue and sleep disturbance are highly prevalent in pwMS and have been identified as predictors of depression. This highlights the importance of considering these factors concurrently during clinical assessments. Depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance were associated with lower HRQoL and higher disability scores.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations, among which clinical variables of MS that would a priori be related to depression, and QoL such as pain, spasticity, and sphincter involvement were not considered. Additionally, socioeconomic variables such as employment, social support, availability of caregivers, economic and educational levels, and/or alcohol consumption were not considered.

ConclusionsDepressive symptoms are highly prevalent among patients with MS, with rates up to 40.5% as indicated by the BDI. Our study demonstrates that MS patients experiencing depressive symptoms have higher disability scores, longer ambulation times, worse cognitive function, and poorer sleep quality. They also exhibit significantly increased fatigue and daytime sleepiness, leading to substantially lower physical and mental QoL scores. These findings underscore the critical need for routine screening and comprehensive management of depression in individuals with MS.

FundingThis research received no external funding.

Disclosure statementThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Author contributionsEA-C and RV-G contributed to the study design and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AC-M and CM S contributed to acquisition of data. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Patient consentPatients were informed that their files could be used retrospectively and anonymously for research purposes unless they objected, and after reading an information sheet, all provided written informed consent.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and approved by the local ethics committee.

None.