Dear Sir,

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) encompasses dementia (essential for diagnosis) and core clinical features (fluctuating cognition/alertness, recurrent visual hallucinations, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, and parkinsonism).1 The prodromal phase of DLB includes mild cognitive impairment, delirium-onset, and psychiatric-onset presentations.2 In the early stages, prominent memory impairment may not occur, but attention deficits, executive dysfunction, and visuoperceptual disability may be prominent.1

Bálint syndrome (BS) is an uncommon and disabling higher-level visual cognitive disorder consisting of optic ataxia, oculomotor apraxia, and simultanagnosia.3 It is usually due to lesions involving bilateral parieto-occipital cortices, such as stroke, corticobasal degeneration, Alzheimer's disease, Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease, central nervous system infections, autoimmune encephalitis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, traumatic brain injury, neoplasms, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, among others.3 BS has rarely been associated with DLB,4 despite the fact that the topographic pattern of hypometabolism mainly includes the occipital areas, visual association cortices, and posterior parietotemporal regions.6

DLB and Parkinson's disease-associated cognitive impairment (PD-MCI, PDD) are included within the broader concept of dementias associated with Lewy bodies,7 classically differentiated by the so-called “one-year rule”.8 In DLB, cognitive symptoms should appear before, at the same time, or shortly after motor symptoms, while in PDD, dementia should occur at least 1 year after the onset of parkinsonism. The new criteria for the diagnosis of PD published by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society have proposed the abolition of the “one-year rule”, allowing the diagnosis of PD in patients with early onset of cognitive impairment.9

It is noteworthy to mention posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), a clinical–radiological syndrome characterized by the gradual deterioration of visual processing, including the presence of BS and other posterior cognitive functions, and atrophy of posterior brain regions.10 In early phases, memory and language remain relatively intact.6 While frequently regarded as a “visual variant” of Alzheimer's disease, several additional pathological substrates are identifiable, including DLB-PCA-Plus (DLB).11

Dorsal and ventral streams are 2 major pathways that emanate from the primary visual cortex and play pivotal roles in perceiving and interacting with the world. Both are crucial for understanding higher-order visual symptoms.12 In the BS context, higher-order visual symptoms involve both streams, predominantly the dorsal stream.13,14 Simultanagnosia is believed to result from bilateral damage to the dorsal stream, particularly parieto-occipital regions.12 Optic ataxia also implicates the dorsal stream.14

We herein report a novel video case of BS in the DLB setting, which would reinforce the occurrence of this rare phenotypic variant.

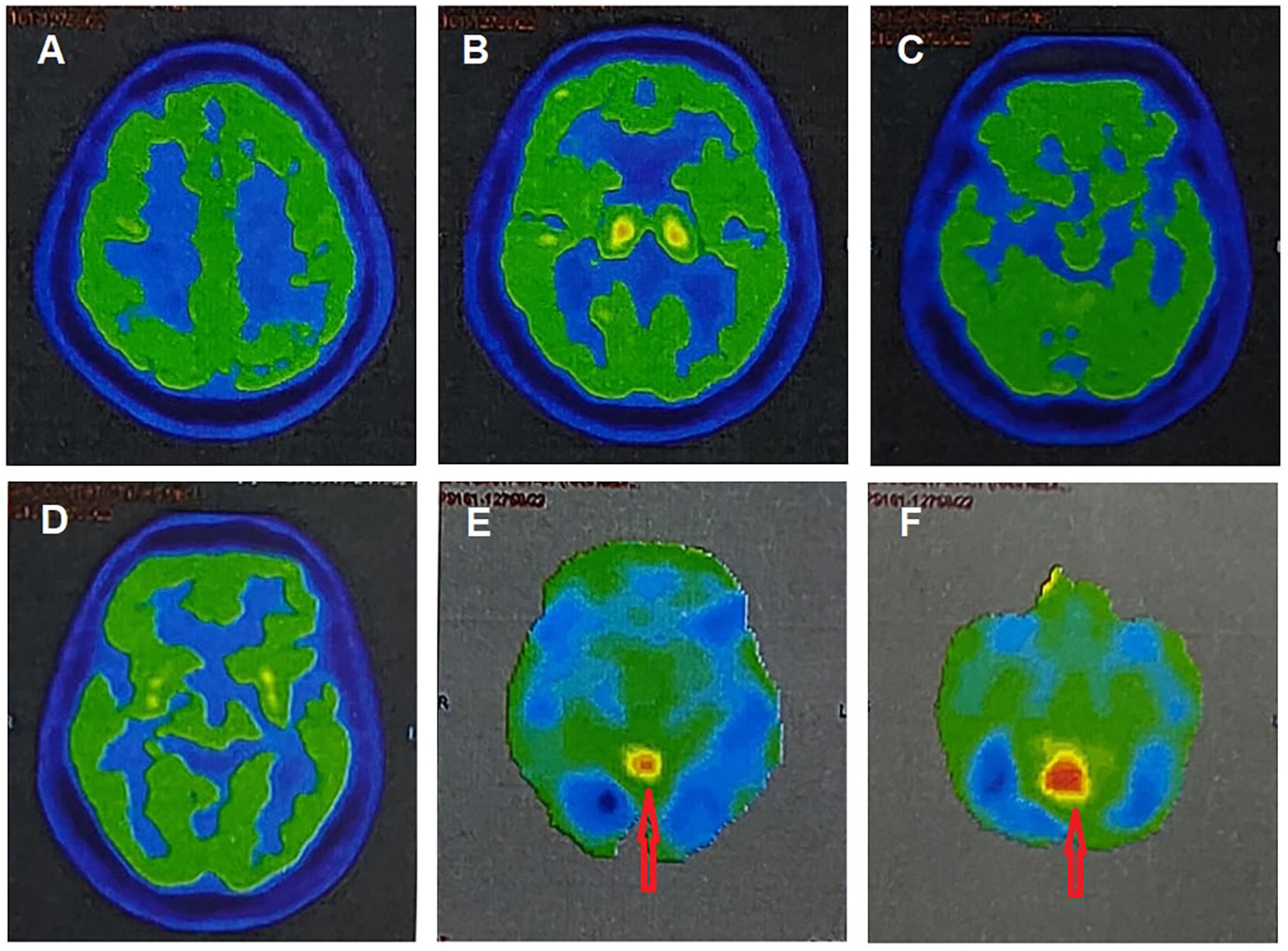

A 73-year-old male from rural West Bengal, India, with a history of well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension, had been diagnosed with PD 3 years ago in another center based on symmetric bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, multiple central pain symptoms, severe constipation, obsession, depression, anxiety, along with visual hallucinations, syncopal attacks, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD). He also presented vocal tics, bruxism, motor perseverance, and new-onset cognitive impairment (naming, calculation, navigational difficulties, and memory dysfunction). He had been prescribed levodopa–carbidopa (300–30 mg/day). After another 6 months of follow-up, he deteriorated in behavioral (obsessive features, nasal/vocal tics, and bruxism) and cognitive symptoms (decreased cognitive flexibility, memory impairment, executive dysfunction, fluctuating attention, difficulties in naming, calculation and navigation, and semantic paraphasias). After another 6 months of follow-up, the patient developed marked behavioral abnormalities, incoherent speech, visual hallucinations, profuse impulsivity, sundowning, and rapid parkinsonian features deterioration refractory to levodopa with significant gait impairment and recurrent falls, history of long-term clinical RBD, recurrent visual hallucinations, systemized delusions, recurrent syncopal attacks, and recent-onset higher-level visual symptoms combining optic ataxia, simultanagnosia, and oculomotor apraxia. All suggestive of BS in the backdrop of probable DLB (video). A brain computerized tomography scan revealed relative preservation of medial temporal lobe structures. Fluorine-18-labeled-fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT revealed a generalized hypometabolism (mainly in the bilateral parieto-temporal cortex, but also in decrescendo order, prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, cingulate cortex, and occipital cortex) with reduced occipital activity and a cingulate island as supportive DLB biomarker (Fig. 1E–F), contributing to DLB diagnosis.

Axial fluorine-18 labeled fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography of the brain showing a mild–moderate hypometabolism in the prefrontal (A), basal ganglia (B), cingulate and occipital cortices (C–D), and moderate–severe hypometabolism in the bilateral parieto-temporal cortex (C–D). Notice a cingulate island sign (red arrows) (E–F). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

It should be noted that although PD and DLB may be 2 phenotypic manifestations of the same disease, according to current classification systems in DLB, parkinsonism is usually late, less prominent, and more symmetrical.1,2,15 Besides, the sign of the cingulate island, although described as very specific to DLB, serves above all to differentiate DLB from Alzheimer's disease.6

As far as we know, this is the first reported BS video case in the DLB setting. In another DLB case, BS appeared at the beginning of the disease,4 and in a case series of 4 parkinsonism cases, BS appeared during the course, helping to diagnose DLB.5

While BS is not typically a DLB hallmark, if it does present in a DLB patient, it could offer insights into disease progression for the following reasons. First, BS in DLB suggests that Lewy body pathology involves the posterior parietal regions, indicating disease progression early in the course, but also later, as in this case.6 Second, DLB is often associated with visual hallucinations and other visual disturbances.1 BS could represent an evolution or intensification of these visual problems, thus worsening the underlying disease process. Third, both DLB and PD are alpha-synucleinopathies. Patients with PD can exhibit symptoms resembling BS, mainly when the disease affects posterior cortical areas.11 The appearance of BS might represent an overlap in pathological processes seen in both diseases, marking a more advanced stage of DLB. Fourth, BS makes it harder for patients to interact with their environment effectively as a marker of disease progression. Finally, significant parieto-occipital dysfunction onset (as seen in BS) could be indicative of overall cognitive decline.

Ours and previously published cases4,5 open the debate of whether the BS presentation in a DLB could be a novel phenotype. Finally, although BS is not a primary DLB feature, its presence in a patient with other DLB symptoms might aid in painting a more comprehensive clinical picture.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Video showing difficulties in simultaneous perception of objects, i.e., he cannot grasp or point accurately to objects within the range of his vision, suggestive of simultanagnosia. Also, optic ataxia, i.e., the patient cannot point to the tip of the percussion hammer, and oculomotor apraxia is noticed.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurop.2024.100171.

Ethical considerationsWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient participating in the study (consent for research).

Author contributionsAll authors contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript; each fulfilled the criterion as established by the ICMJE.

Study fundingNil.

J. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the European Commission (grant ICT-2011- 287739, NeuroTREMOR), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant RTC-2015-3967-1, NetMD—platform for the tracking of movement disorder), and the Spanish Health Research Agency (grant FIS PI12/01602 and grant FIS PI16/00451).