Identifying predictors of dementia and differences in mortality rates between dementia subtypes could contribute to the development of preventive strategies.

AimsTo identify risk factors for mortality in patients with dementia and to determine the incidence of mortality.

MethodologyWe conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, following the PRISMA 2020 statement. The search was performed on the PubMed/Medline, Embase, and BIREME/LILACS databases.

ResultsOur meta-analysis included 15 observational studies, reporting data from 177 663 patients with dementia. The following predictors of mortality were identified: male sex (OR: 1.40 [95% CI, 1.22–1.62]), white ethnicity (OR: 1.50 [95% CI, 1.30–1.73]), Alzheimer disease (OR: 1.26 [95% CI, 1.03–1.53]), diabetes mellitus (OR: 1.29 [95% CI, 1.21–1.39]), stroke (OR: 1.25 [95% CI, 1.10–1.41]), pneumonia (OR: 3.00 [95% CI, 2.26–4.00]), Charlson Comorbidity Index (standardised mean difference (SMD): 0.21 [95% CI, 0.18–0.23]), supplemental oxygen therapy (OR: 9.97 [95% CI, 9.49–10.46]), and number of medications (SMD: 0.24 [95% CI, 0.21–0.26]). In patients with Alzheimer disease, the mortality rate was 35% (95% CI, 23%–46%), with a mean follow-up time of 34 months. The incidence of mortality in patients with other types of dementia was 48% (95% CI, 38%–56%), with a mean follow-up time of 70 months.

ConclusionsThe incidence of mortality was higher in patients with dementia other than Alzheimer disease. The type of dementia and the risk factors described should be taken into account when developing prevention strategies.

Identificar factores predictivos y diferencias en las incidencias de mortalidad entre los subtipos de demencia podría ayudar a desarrollar estrategias preventivas.

ObjetivosIdentificar factores de riesgo de mortalidad en pacientes con demencia y determinar la incidencia de mortalidad.

MetodologíaSe realizó una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis según la declaración PRISMA 2020. La búsqueda se realizó en las bases de datos PubMed/Medline, Embase y BIREME/LILACS.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 15 estudios en el metaanálisis, que proporcionaron datos de 177.663 pacientes. Los predictores de mortalidad fueron: sexo masculino OR 1.40 [IC 95% 1.22;1.62], raza blanca OR 1.50 [IC 95% 1.30;1.73], enfermedad de Alzheimer OR 1.26 [IC 95% 1.03, 1.53], diabetes mellitus OR 1.29 [IC 95% 1.21;1.39], enfermedad cerebrovascular OR 1.25 [IC 95% 1.10;1.41], neumonía OR 3.00 [IC 95% 2.26;4.00], índice de comorbilidad de Charlson DME 0.21 [IC 95% 0.18;0.23], oxígeno suplementario OR 9.97 [IC 95% 9.49;10.46] y número de medicamentos DME 0.24 [IC 95% 0.21; 0.26]. En pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer la mortalidad fue del 35% (IC del 95%: 23;46) con una media de 34 meses de seguimiento. La incidencia de mortalidad en pacientes con otros tipos de demencias fue del 48% (IC del 95%: 38;56) a una media de 70 meses de seguimiento.

ConclusionesLa incidencia de mortalidad fue mayor en pacientes con demencias diferente a la enfermedad de Alzheimer. El tipo de demencia y los factores de riesgo descritos deben ser tenidos en cuenta para desarrollar estrategias de prevención.

Dementia is defined as a clinical syndrome characterised by progressive cognitive deterioration, which affects behaviour and impairs the patient's ability to independently perform daily living activities.1 The term dementia encompasses several related neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer disease (AD), vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia, among others.2 At present, nearly 55 million people worldwide have dementia, and the condition's incidence is expected to increase due to population ageing.3,4 In recent decades, there has been an alarming increase in the number of deaths related to dementia4,5; as a result, the condition has become the fifth leading cause of death worldwide, causing 2.4 million deaths per year.5 Dementia is a growing public health concern due to its significant economic burden in terms of both direct (medical care) and indirect costs (unrelated to healthcare provision).3 Therefore, understanding the association between dementia and mortality, as well as the factors involved in this interaction, is essential both for healthcare professionals and for public health policy-makers.6 Several factors involved in mortality burden have been identified, including sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, paraclinical findings, and neuroimaging findings, among others.7,8 Several review articles have been published on the subject.9 The purpose of the present review was to identify mortality risk factors in patients with dementia and to determine the incidence of mortality among these patients.

MethodsWe conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, following the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the 2020 PRISMA declaration (Supplementary Material 1). The research protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database under code CRD42023444526.

PopulationThe exposure group included deceased patients with a diagnosis of dementia and for whom data were available on different variables of interest, which may be predictors of mortality. Among others, these variables included sex, race, ethnicity, living arrangement, functional status, depression, malnutrition, arterial hypertension (AHT), diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE), Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, and Global Deterioration Scale (GDS). The control group included patients with dementia who had not died but for whom data were available on these potential predictors of mortality.

ObjectivesOur primary objective was to identify mortality risk factors in patients with dementia, whereas the secondary objective was to determine the incidence of mortality.

Electronic searchAn electronic search was conducted using the PubMed/MEDLINE, BIREME/LILACS, and Embase databases. We also searched for grey literature on the Google Scholar platform and gathered the studies cited in the references sections. The following search strategy was used: (Dementia) AND (Risk factors) AND (Mortality), gathering all articles regardless of language or year of publication. The literature search was conducted between 28 July and 4 August 2023.

Eligibility criteriaInclusion criteria were as follows: (a) studies including patients with a diagnosis of dementia, regardless of the type; (b) groups had to have been categorised according to mortality and survival; (c) analytic observational studies, such as cohort, case–control, and cross-sectional studies; (d) studies seeking to identify potential mortality risk factors. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) narrative reviews, case reports, case series, or abstracts from communications presented at congresses; (b) experimental or observational studies designed to evaluate the efficacy of a specific intervention or in which selection criteria required that participants were receiving some type of intervention, which may modify the effect of the predictor variables.

Search and selection processThe search and selection process was conducted using the Rayyan Beta platform. Three authors (PTMG, LMV, and APYS) read the titles and abstracts following a blind approach, classifying the studies into 3 categories: excluded, undetermined, and included. The studies initially classified as included or undetermined were read in full text, and were subsequently classified as either included or definitively excluded. Furthermore, 2 authors (LMV and APYS) reviewed the grey literature by reviewing bibliographic references and searching Google Scholar. In the event of disagreement, JSR made the final decision. The Cohen's kappa coefficient was subsequently calculated to determine the agreement of the final selection. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews was used to depict the literature search and study selection process.

Data extractionData extraction was blind, and was conducted by JSR, MASA, and MAOG using an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Office 2019). The following information was extracted: authors' names, year of publication, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, duration of follow-up, incidence of mortality, and mortality risk factors. Information was also gathered on the number of participants in the mortality and survival groups, frequency of events in each group, and mean and standard deviation for numerical variables. PTMG resolved any disagreements.

Evaluation of methodological quality and risk of biasRisk of bias and methodological quality assessment was performed by 3 researchers (LMV, JSR, and MAOG). PTMG resolved any discrepancies. Agreement was determined with the Cohen's kappa coefficient.

Risk of bias was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, a validated tool that is widely used for risk of bias assessment in observational or non-randomised studies.10 The scale evaluates 3 aspects: the selection of the study groups, the comparability of the groups, and the ascertainment of the exposure or outcome of interest.11 Methodological quality was classified as follows: (a) good: 3–4 stars in selection, 1–2 stars in comparability, and 2–3 stars in exposure/outcomes; (b) fair: 2 stars in selection, 1–2 stars in comparability, and 2–3 stars in exposure/outcomes; (c) poor: 0–1 stars in selection, 0 stars in comparability, and 0–1 stars in exposure/outcomes.

LMV, JSR, and MAOG assessed the certainty of evidence using the GRADEpro tool. For each outcome of interest, we analysed the following aspects: number of studies, study design, risk of bias, inconsistencies, indirect evidence, inaccuracy, other considerations, number of events in the mortality and survival groups, and odds ratio (OR) or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We classified the certainty of the evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low, and also classified the importance of each outcome into different categories, creating a table that summarised the GRADE evidence for the associated risk factors. Any disagreements were resolved by PTMG.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4. We used the Mantel–Haenszel test with the random-effects model to calculate the OR and 95% CI of qualitative variables. For numerical variables, we used the inverse variance method with the random effects model to determine the SMD and its 95% CI. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated with the I2 test (with values >50% considered to indicate statistical heterogeneity).12 We also performed a sensitivity analysis, and stratified studies according to type of dementia and such methodological factors as quality and epidemiological design. Results were represented graphically with a forest plot, and publication bias was evaluated with a funnel plot. For the meta-analysis of the cumulative incidence of mortality, we used MAVIS (Meta Analysis via Shiny) with the correlations template. Several forest plots were created to calculate global effect size in relation to the cumulative incidence and follow-up time in months.

ResultsThe article selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Fig. 1). We identified the titles and abstracts of 5829 articles, 1666 of which were duplicates. We read the titles and abstracts of 4163 studies, 4089 of which were excluded after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Seventy-four articles were read in full text, and 48 were excluded for the following reasons: 25 due to their methodological design, 15 due to the type of population, 3 due to the type of outcomes, and 5 due to the intervention. A total of 26 studies were finally included in the qualitative review,13–38 and 15 studies in the meta-analysis.15–18,20,25,27,28,31–34,36–38 Agreement in the final selection of studies was moderate (kappa coefficient=0.53).

The qualitative review analysed 26 studies, which provided data on 319 132 patients diagnosed with dementia, with a mean (SD) age of 79.8 (4.4) years.13–38 Participants showed a female predominance in 20 studies (76.9%).13,15,19–23,25–30,32–36,38,39 The 26 studies analysed included patients with the following types of dementia: any type in 15 studies (57.7%); AD in 6 (23.1%); AD and vascular dementia in 2 (7.7%); senile dementia, AD, and vascular dementia in 1 (3.3%); advanced dementia in 1 (3.3%), and Lewy body dementia in 1 (3.3%).13–38 The greatest numbers of studies were published in the following countries: Taiwan (3 studies; 11.5%), Sweden (3; 11.5%), the Netherlands (3; 11.5%), Spain (2; 7.7%), and the United States (2; 7.7%).13–38 By year, the greatest numbers of studies were published in 2020 (4 studies; 15.4%), 2019 (4; 15.4%), 2023 (3; 11.5%), and 2018 (3; 11.5%); the oldest study was published in 1991.13–38

The patients included in the studies were gathered from the hospital setting in 8 studies (30.7%),16,22,23,28,30–32,37 from population registries and large dementia databases in 7 (26.9%),14,18,19,21,29,33,39 from geriatric residences or long-term care institutions in 7 (26.9%),15,17,20,25,26,34,38 and population-based studies, recruitment centres, or primary care centres in 4 (15.5%).13,27,35,36 Diagnosis of dementia was based on the DSM-III criteria in 1 study (3.8%) and the DSM-IV criteria in 7 (26.9%).13,15,18–20,30,34,38 The remaining studies were based on clinical registries, registries of dementia databases, and ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes.19,21–23,25–30,32–36,39 Supplementary Material 2 presents the general characteristics of all the studies included in the qualitative review.

Risk of bias assessmentTwenty-five studies were cohort studies,13–31,33–38 56% of which were prospective.13–15,17–19,22,25,30,31,33,35,36,38 Regarding risk of bias, 80.7% of studies presented good methodological quality according to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, whereas 19.3% had fair methodological quality (Table 1).13–38 Inter-rater agreement was moderate (kappa coefficient=0.58).

Risk of bias assessment and methodological quality according to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

| Study | Type of study | Selection | Comparability | Exposure/outcomes | Methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mostafaei et al.,33 2023 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Kaur et al.,28 2023 | Retrospective cohort | +++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Kayahan and Naharci,37 2023 | Retrospective cohort | +++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Armstrong et al.,14 2022 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Meng et al.,32 2022 | Cross-sectional, analytical | ++ | + | + | Fair |

| Cullum et al.,19 2020 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Piovezan et al.,35 2020 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | + | +++ | Good |

| Golüke et al.,23 2020 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | + | ++ | Good |

| Huyer et al.,27 2020 | Retrospective cohort | +++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Golüke et al.,22 2019 | Retrospective cohort | ++ | + | ++ | Fair |

| Chen et al.,17 2019 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Haaksma et al.,24 2019 | Retrospective cohort | +++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Hsieh et al.,26 2019 | Retrospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Lewis et al.,29 2018 | Retrospective cohort | ++ | + | ++ | Fair |

| Chen et al.,16 2018 | Retrospective cohort | +++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Rhodius-Meester et al.,31 2018 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Mahmoudi et al.,30 2017 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | + | +++ | Good |

| Connors et al.,18 2016 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Roehr et al.,36 2015 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Garcia-Ptacek et al.,21 2014 | Retrospective cohort | +++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Navarro-Gil et al.,34 2014 | Retrospective cohort | ++ | + | ++ | Fair |

| Hicks et al.,25 2010 | Prospective cohort | ++++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Suh et al.,38 2005 | Prospective cohort | +++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Álvarez-Fernández et al.,13 2005 | Prospective cohort | +++ | ++ | +++ | Good |

| Gambassi et al.,20 1999 | Retrospective cohort | +++ | ++ | ++ | Good |

| Burns et al.,15 1991 | Prospective cohort | ++ | ++ | ++ | Fair |

Good: 3–4 stars in selection, 1–2 stars in comparability, and 2–3 stars in exposure/outcomes. Fair: 2 stars in selection, 1–2 stars in comparability, and 2–3 stars in exposure/outcomes. Poor: 0–1 stars in selection, 0 stars in comparability, and 0–1 stars in exposure/outcomes.

A number of risk factors were identified, including sociodemographic variables, dementia-related aspects, comorbidities, and treatments.13–38

Sociodemographic risk factors included advanced age,15,16,18–20,22,27–36,38,39 male sex,14–16,18,20–23,27,31,33,35,36,39 white ethnicity,14 non-Hispanic ethnicity,14 living with a partner,22 living alone, or institutionalisation.21,39 The following dementia-related aspects were analysed: age at symptom onset,14 AD progression time,38 different types of dementia (AD, vascular dementia, mixed dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, Parkinson's disease),14,21,36 neuropsychiatric symptoms,35,38 cognitive impairment,19,31,35 severity and changes in severity of dementia,18 lowest cognitive score since diagnosis, and functional dependence.28

The associated comorbidities included DM,16,20,27,32–34 AHT,34 COPD,27 chronic heart failure,16,27 chronic kidney disease,16,27 cerebrovascular accidents,16,27 coronary artery disease,16 dyslipidaemia,16 cirrhosis,16 cancer,16,33 pneumonia,13,28 pressure ulcers,16,20,26 dysphagia,28 malnutrition,17,20,30,35 depression,15,38 smoking,14 cardiovascular disease,20,23 digestive disorders,32 respiratory disorders,32 urinary disorders,32 and hydroelectrolytic alterations.26 Regarding diagnostic test results, alterations in serum levels of urea28 and albumin (<3.5 g/dL)28 and global and hippocampal atrophy on MRI were identified as predictors of mortality.31

The tools that served as predictors were the MMSE,14,15,21,29,39 Neuropsychiatric Inventory - Questionnaire,14 GDS,38 Geriatric Depression Scale,14 CDR,14,37 and CCI,17,33,39 whereas treatment-related predictors of mortality included supplemental oxygen therapy,16,26 number of medications,14,18,21,39 use of antipsychotics,18,19 use of a permanent urinary catheter,26 and use of a nasogastric tube.13,16 Other potential predictors of mortality were lack of participation in leisure activities34 and worsening of health status over the previous 12 months.34

Quantitative reviewThe quantitative review included 15 studies, reporting a total of 177 663 patients diagnosed with dementia, 98 342 of whom were deceased (Supplementary Material 3).15–18,20,25,27,28,31–34,36–38 The following variables presented a significant association with mortality in the meta-analysis (Supplementary Material 3).

Male sexMale sex was identified as a risk factor for mortality, with an OR of 1.40 (95% CI, 1.22–1.62).15,17,18,25,31,33,36,38 The global analysis revealed high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 99%),15–18,20,25,27,28,31,33,34,36–38 which was attributed to the epidemiological design (Supplementary Material 3). Therefore, when stratifying by prospective cohort studies, heterogeneity decreased significantly (I2 of 23%) (Fig. 2).15,17,18,25,31,33,36,38 Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis revealed that the findings were robust, and no publication bias was detected (Supplementary Material 3).

White ethnicityWhite ethnicity was identified as a risk factor for mortality in patients with dementia, with an OR of 1.5 (95% CI, 1.30–1.73); no statistical heterogeneity was observed (I2 of 0%) (Fig. 2).20,25 Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis revealed that the findings were robust, and no publication bias was detected (Supplementary Material 3).

Alzheimer diseasePresence of AD was identified as a significant risk factor for mortality, with an OR of 1.26 (95% CI, 1.03–1.53) (Fig. 2).18,25,33 No statistical heterogeneity was observed (I2 of 39%). However, the sensitivity analysis suggested that findings were not robust, although no publication bias was detected (Supplementary Material 3).

Cerebrovascular diseasePresence of cerebrovascular disease was identified as a significant risk factor for mortality, with an OR of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.10–1.41) (Fig. 2).17,20,36 The global analysis revealed high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 88%),16,17,20,27,36 which was attributed to the type of dementia and the epidemiological design (Supplementary Material 3). For that reason, heterogeneity decreased significantly when controlling for these factors (I2 of 0%).17,20,36 No publication bias was detected, and the sensitivity analysis suggested that findings were robust (Supplementary Material 3).

PneumoniaPneumonia was a risk factor for mortality in patients with dementia, with an OR of 3 (95% CI, 2.26–4.00).25,28 No statistical heterogeneity was observed (I2 of 0%) (Fig. 2). The sensitivity analysis revealed that the findings were robust, and no publication bias was detected (Supplementary Material 3).

Charlson Comorbidity IndexThe CCI was found to be a risk factor for mortality, with an SMD of 0.21 (95% CI, 0.18–0.23)17,33,37; no statistical heterogeneity was observed (Fig. 3). The sensitivity analysis revealed that the findings were robust, and no publication bias was detected (Supplementary Material 3).

Supplemental oxygen therapyPatients requiring supplemental oxygen therapy were at greater risk of mortality, with an OR of 9.97 (95% CI, 9.49–10.46).16 No statistical heterogeneity was observed (Fig. 2). Furthermore, no publication bias was detected, and the sensitivity analysis suggested that findings were robust (Supplementary Material 3).

Number of medicationsThe patients receiving greater numbers of medications present a higher risk of mortality, with an SMD of 0.24 (95% CI, 0.21–0.26) (Fig. 3).18,31,33 The sensitivity analysis revealed that the findings were robust, and no publication bias was detected (Supplementary Material 3).

Advanced age in Alzheimer diseaseAdvanced age was a risk factor for mortality in patients with AD, with an SMD of 0.49 (95% CI, 0.35–0.63) (Fig. 3).15,17,31,38 The sensitivity analysis revealed that the findings were robust, and no publication bias was detected (Supplementary Material 3).

Cardiovascular disease in patients with Alzheimer diseasePatients with AD and a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease presented greater risk of mortality, with an OR of 1.48 (95% CI, 1.36–1.62).17,20,31 The global analysis detected great statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 73%), which was explained by the type of dementia.17,20,31 No publication bias was detected, and the sensitivity analysis suggested that findings were robust (Supplementary Material 3).

Certainty of evidenceTable 2 presents the GRADE levels of evidence. AD was classed as a risk factor with a very low level of certainty. Male sex, white ethnicity, DM, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease in patients with AD, CCI, and number of medications were considered to have a low level of certainty. The level of certainty was moderate for pneumonia and advanced age in AD, and high for supplemental oxygen therapy.

Certainty of evidence (GRADE criteria) for risk factors for mortality in patients with dementia.

| Assessment of certainty | No. patients | Effect | Certainty | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Further considerations | Mortality | Survival | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||

| Male sex | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 8791/19858 (44.3%) | 4050/10720 (37.8%) | OR: 1.40 (1.22–1.62) | 82 more per 1000 (48 more to 118 more) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| White ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 4300/4662 (92.2%) | 4056/4561 (88.9%) | OR: 1.50 (1.30–1.73) | 34 more per 1000 (23 more to 44 more) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| Alzheimer disease | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Strong suspicion of publication bias | 5391/19116 (28.2%) | 2341/9809 (23.9%) | OR: 1.26 (1.03–1.53) | 44 more per 1000 (5 more to 85 more) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | Critical |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 3074/19280 (15.9%) | 1276/10089 (12.6%) | OR: 1.29 (1.20–1.38) | 31 more per 1000 (22 more to 40 more) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 524/5029 (10.4%) | 410/4842 (8.5%) | OR: 1.27 (1.11–1.46) | 20 more per 1000 (8 more to 34 more) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| Pneumonia | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Strong association | 148/411 (36.0%) | 132/789 (16.7%) | OR: 3.00 (2.26–4.00) | 209 more per 1000 (145 more to 278 more) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate | Critical |

| Supplemental oxygen therapy | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very strong association | 14 344/20542 (69.8%) | 3156/16747 (18.8%) | OR: 9.97 (9.49–10.46) | 510 more per 1000 (499 more to 520 more) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Critical |

| Cardiovascular disease in patients with AD | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1635/4875 (33.5%) | 1278/5089 (25.1%) | OR: 1.48 (1.36–1.62) | 81 more per 1000 (62 more to 101 more) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| CCI | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 18 630 | 9585 | – | SMD 0.21 SD higher (0.18 higher to 0.23 higher) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| No. medications | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 19 236 | 10 182 | – | SMD 0.24 SD higher (0.21 higher to 0.26 higher) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| Advanced age in patients with AD | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Dose–response gradient | 375 | 755 | – | SMD 0.49 SD higher (0.35 higher to 0.63 higher) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate | Critical |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AD: Alzheimer disease; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference.

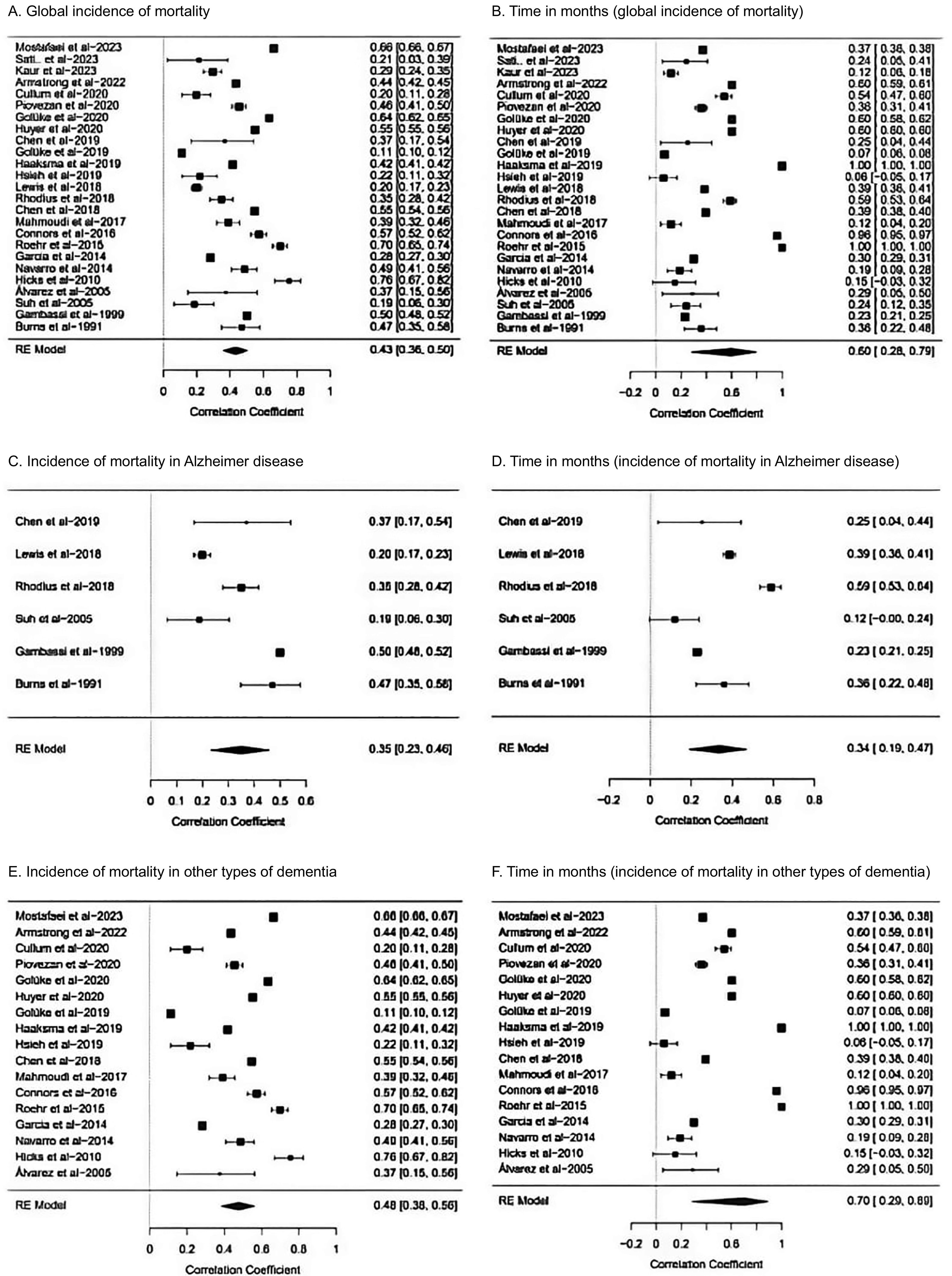

To evaluate the incidence of mortality, we analysed a total of 25 cohort studies.13–31,33–38 The cumulative incidence of global mortality in patients with dementia was 43% (95% CI, 36%–50%), with a mean follow-up time of 60 months (95% CI, 28–79) (Fig. 4A and B).13–31,33–38 When the analysis was limited to patients with AD, mortality was 35% (95% CI, 23%–46%), with a mean follow-up time of 34 months (95% CI, 19–47) (Fig. 4C and D).15,17,20,29,31,38 The studies including other types of dementia reported higher mortality rates, at 48% (95% CI, 38%–56%) at a mean follow-up time of 70 months (95% CI, 29–89) (Fig. 4E and F).13,14,16,18,19,21,22,25–27,30,33–36,39 These analyses presented great statistical heterogeneity, which was nonetheless controlled using a random effects model.

The reported data were insufficient to conduct a meta-analysis of each specific type of dementia (for dementias other than AD).

DiscussionOur findings suggest that several sociodemographic factors may act as predictors of mortality in patients with dementia; these include advanced age, male sex, and white ethnicity. These results are consistent with those reported in a systematic review by van de Vorst et al.9 and an observational study by Liang et al.,40 who also identified advanced age and male sex as predictors of mortality in this population.9,40 Such comorbidities as DM, cerebrovascular disease, and pneumonia were identified as predictors of mortality in the meta-analysis. These results are in line with those reported by Sakai et al.,41 Barba et al.,42 and van de Vorst et al.,9 who also underscored the relevance of these comorbidities as risk factors for mortality in patients with dementia.9,41,42

Cardiovascular diseases have traditionally been regarded as mortality risk factors in different populations.43 In the present review, we identified a significant association between cardiovascular diseases and mortality; this finding is also supported by Alonso et al.43 and Martín et al.44 Both studies evaluated patients with dementia and concluded that said comorbidities acted as predictors of mortality.43,44 CCI is a widely used tool for the quantification and assessment of comorbidity burden, and has been regarded as a significant predictor of mortality in our study, in line with the results reported previously by Tang et al.45

Polypharmacy is associated with a greater number of adverse reactions, increased economic costs, and a greater morbidity and mortality burden.46 Our review found that the participants with dementia who were taking a greater number of medications presented a greater risk of mortality. According to Russ et al.,47 patients with chronic respiratory diseases present greater risk of developing dementia in old age.47 In our study, patients with dementia and requiring supplemental oxygen therapy presented a higher mortality risk. Furthermore, the incidence of mortality was significantly higher in the studies including patients with types of dementia other than AD, but with a longer mean follow-up time. Similarly to these findings, Staekenborg et al.48 and Ono et al.49 also reported an increase in mortality in patients with other types of dementia.

Our study is not without limitations. Firstly, we found very few studies of certain types of dementia, such as Lewy body dementia or frontotemporal dementia.37 Secondly, the reviewed studies presented great heterogeneity, which we attempted to control for using different stratification methods and statistical analyses. Furthermore, in several studies included in this review, the diagnosis of dementia was based on clinical assessments that lack specificity.19,21–23,25–30,32–36,39 Therefore, future studies should establish clear diagnostic criteria for patient selection and analyse the results by type of dementia.

Lastly, our findings may encourage public health policy-makers to implement prevention programmes designed specifically for these populations. Further research should be conducted to identify the risk factors and mortality of each type of dementia, apart from AD. These strategies may significantly improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients with dementia.

ConclusionsThe incidence of mortality was greater among patients with types of dementia other than AD. It is essential to consider the type of dementia and the associated risk factors to design effective prevention strategies.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Ethical considerationsThis study complied with good clinical practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

This type of study does not require approval by an ethics committee.

Informed consentNo patient data were included, and therefore informed consent was not needed.