Given the high prevalence of primary headache in the young population, and the rate of pregnancy in this age group, it is unsurprising that pregnant women present a high likelihood of consulting due to headache.

ObjectivesThis study seeks to determine the main aetiologies and predictors of headache and the usefulness of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (third edition-beta; ICHD-3 beta) for differentiating primary from non-primary headaches in pregnant women at the emergency department.

Patients and methodsWe performed a cross-sectional study comparing the prevalence of patients meeting the ICHD-3 beta criteria, associated symptoms, history of headache, and demographic features between primary and non-primary headaches.

ResultsHeadache was responsible for 142 out of 2952 admissions (4.8%). Headache was primary, non-primary, or unclassified in 66.9%, 27.4%, and 5.6% of cases, respectively. Migraine and headache associated with hypertensive disorders were the most frequent aetiologies for primary and non-primary headaches: 91.6% and 31.4% of cases, respectively. The factors associated with primary headache were fulfilling the ICHD-3 beta criteria (OR: 23.5; 95% CI, 12.5–34.5; p<0.001), history of migraine (OR: 2.85; 95% CI, 1.18–5.94; p=0.013), history of similar episodes (OR: 6.4; 95% CI, 2.78–14.0; p<0.001), and description of phosphenes (OR: 4.2; 95% CI, 1.5–11.68; p=0.02). The factors associated with non-primary headaches were fever (OR: 12.8; 95% CI, 1.38–119; p=0.016) and mean arterial blood pressure greater than 106.6 (OR: 2.6; 95% CI, 1.7–3.5; p=0.03).

ConclusionIn our study, the ICHD-3 beta criteria were useful for differentiating primary from non-primary headaches in pregnant women. History of migraine, history of similar episodes, phosphenes, fever, and high arterial blood pressure were also valuable predictors.

Debido a la alta prevalencia de cefaleas primarias en la población general joven y la tasa de embarazos en este rango de edad, no sorprende encontrar una alta probabilidad de consultas por dolor de cabeza durante el periodo gestacional.

ObjetivosDeterminar etiologías, predictores y utilidad de los criterios ICHD-3 beta para diferenciar cefaleas primarias de las no primarias en mujeres embarazadas en Urgencias.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio transversal que compara la prevalencia de pacientes que reúnen criterios ICHD-3 beta, síntomas asociados, antecedentes de cefalea y características demográficas entre la cefalea primaria y la no primaria.

ResultadosLa cefalea fue responsable de 142 (4,8%) de 2.952 admisiones. La cefalea primaria, la no primaria y la no clasificada fueron del 66,9, 27,4 y 5,6%, respectivamente. La migraña y la cefalea asociada con trastornos hipertensivos fueron las etiologías más frecuentes para los grupos primarios y no primarios: 91,6 y 31,4%, respectivamente. Fueron factores asociados con la cefalea primaria: reunir criterios ICHD-3 beta (OR 23,5; IC 95% 12,5-34,5; p<0,001), antecedente de migraña (OR 2,85; IC 95% 1,18-5,94; p=0,013), haber presentado episodios similares (OR 6,4; IC 95% 2,78-14,0; p<0,001) y fosfenos (OR 4,2; IC 95% 1,5-11,68; p=0,02). Fueron factores asociados con etiologías no primarias: fiebre (OR 12,8; IC 95% 1,38-119; p=0,016) y presión arterial media superior a 106,6 (OR 2,6; IC 95% 1,7-3,5; p=0,03).

ConclusiónLos criterios ICHD-3 beta fueron útiles para diferenciar las cefaleas primarias de las no primarias. Esto también es válido para antecedentes de migraña, episodios similares, fosfenos, fiebre y presión arterial alta.

Taking into account the estimated pregnancy rate of 105.5 pregnancies per 1000 women aged 15–441 and that the prevalence of headache disorders calculated between 86 and 97% in the general population aged 18–49,2 it is unsurprising that a high proportion of pregnant women visit the Emergency Department with headache as the main complain, especially considering that most of the headache syndromes are more frequent in middle-aged women.3

Pregnancy is a natural stage in which several physiological changes can occur. Some of these changes involve the immunological,4 hematological5 and endocrine systems6 and could modify homeostatic variables, contributing to the occurrence of infectious, tumoral or vascular conditions in which headache could be one of the clinical manifestations.7 In spite of primary headaches being more prevalent, secondary conditions are always considered when pregnant women visit the Emergency Department with headache as chief complain. The previous statements, along with warnings related to diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions encourage us to find tools that allow clinicians to differentiate those cases in which it is necessary an extended work up from those cases in which a symptomatic treatment is enough.

Due to the absence of biological markers to perform an accurate diagnosis, especially for primary headaches, the International Headache Society (IHS) recommends the international classification for headache disorders (ICHD)8 as a useful tool to determine the most precise diagnosis. This classification is reliable when applied in the clinical setting9,10 and, in consideration that traditional red flags (immunosuppression, age over 50, abnormal neuro exam, sudden onset headache, among others) could be absent in these patients, we sought to establish the usefulness of this classification, in its latest version, ICHD3b, to differentiate primary vs non primary headaches in pregnant women.

Patients and methodsDuring eight weeks, we enrolled all the patients who visited the obstetric emergency room-triage area consulting with headache as chief complaint. We excluded patients with recent history of cranial trauma or neurological conditions which could affect their capability to provide information. All the patients were interviewed in order to obtain clinical information with respect to duration, number of episodes, type of pain, associated symptoms, alleviating and aggravating factors, and medical history in order to determine variables included in the International Headache Society's Classification criteria (ICHD 3). To facilitate the statistical approach, patients were classified as primary vs non-primary headaches, the last group included secondary etiologies and neuralgias. A Headache specialist performed a physical exam, emphasizing on neurological exploration. Following ICHD 3 classification parameters, patients were classified as primary or non-primary (secondary and neuralgias) headaches. Written informed consent was required. Those patients with a primary headache diagnosis were treated according to institutional protocols and were followed up as outpatients by means of phone call communication after 48h to assure improvement in symptoms. Those with persistence of symptoms were asked to visit to the ED again. The group with diagnosis of non-primary headaches was followed up in the hospital for further evaluation and treatment in order to determine the precise etiology of the headache. The work up process varied according to the clinical suspicion in every case. Follow up was made until resolution of pain was confirmed in the primary group and when a diagnosis was determined in the subjects with non-primary etiologies; those cases in which ICHD3 criteria were not successfully fulfilled, lumbar puncture, including pressure, brain MRI, brain MRV were normal, and regardless the outcome, were considered unclassified cases. We compared the prevalence of associated factors in order to determine the likelihood of primary vs non-primary headaches. These factors were age over 50, onset characteristics and associated symptoms, history of immunological disorders, history of migraine, tension type headache or similar episodes to the current pain. We also compared the prevalence of any analgesic treatment before consultation and fulfilling ICHD 3 criteria between both groups. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

A statistical analysis using descriptive statistics by means of frequencies was performed. Association measures were showed using relative risks, confidence intervals and p values, which were considered significant when they were lower than 0.05. Mean differences were calculated by using T test. Analysis were performed using STATA 14.

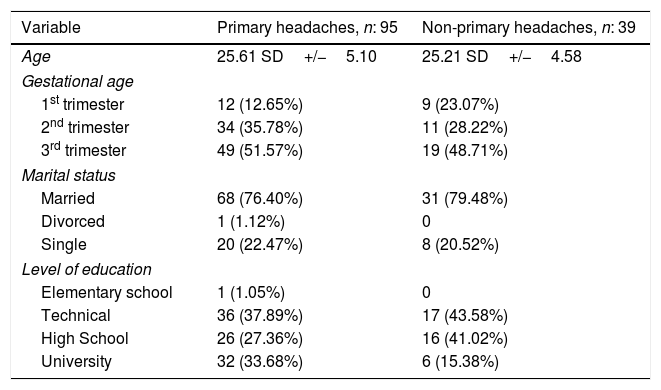

ResultsHeadache was responsible for 142(4.8%) out of 2952 admissions over a period of 8 weeks. Middle-aged women were the most affected group. Most of them were at the third trimester of pregnancy. Magnetic Resonance Imaging was performed in 51 cases, 25 of those were complemented with venography, and lumbar puncture was performed in 10 cases. In 48.2% of the cases patients used analgesics before visiting the ED and 11.5% had consulted before due to the same headache episode. None of these variables was statistically significant when comparing primary vs non-primary headaches (p<0.05) for all cases. Duration of Headache episode at the visit was longer in non-primary headaches vs primary headaches: 48.6h vs 28.5h, p: 0.04.

With respect to etiologies, primary Headaches were the most frequent causes followed by secondary etiologies and neuralgias, respectively. 5.6% of the cases could not be classified following ICHD 3 criteria, Table 1. 10 patients could not be accounted for during follow up.

Demographic characteristics.

| Variable | Primary headaches, n: 95 | Non-primary headaches, n: 39 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 25.61 SD+/−5.10 | 25.21 SD+/−4.58 |

| Gestational age | ||

| 1st trimester | 12 (12.65%) | 9 (23.07%) |

| 2nd trimester | 34 (35.78%) | 11 (28.22%) |

| 3rd trimester | 49 (51.57%) | 19 (48.71%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 68 (76.40%) | 31 (79.48%) |

| Divorced | 1 (1.12%) | 0 |

| Single | 20 (22.47%) | 8 (20.52%) |

| Level of education | ||

| Elementary school | 1 (1.05%) | 0 |

| Technical | 36 (37.89%) | 17 (43.58%) |

| High School | 26 (27.36%) | 16 (41.02%) |

| University | 32 (33.68%) | 6 (15.38%) |

SD: Standard Deviation. Unclassified cases were excluded from this table.

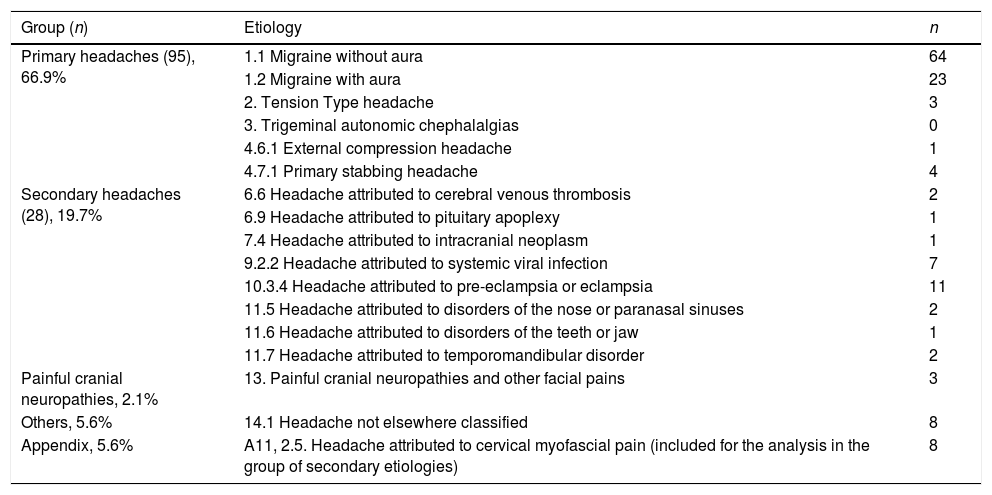

Migraine accounted for the main etiologies in the primary group. Tension type headache (TTH) was a low frequency group and in neither case trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) were diagnosed. In the group of non-primary headaches (secondary etiologies and neuralgias) the 3 main conditions were Headache attributed to preeclampsia, cervical myofascial pain and headache associated with systemic infections, Table 2.

Etiologies according to ICHD 3 classification.

| Group (n) | Etiology | n |

|---|---|---|

| Primary headaches (95), 66.9% | 1.1 Migraine without aura | 64 |

| 1.2 Migraine with aura | 23 | |

| 2. Tension Type headache | 3 | |

| 3. Trigeminal autonomic chephalalgias | 0 | |

| 4.6.1 External compression headache | 1 | |

| 4.7.1 Primary stabbing headache | 4 | |

| Secondary headaches (28), 19.7% | 6.6 Headache attributed to cerebral venous thrombosis | 2 |

| 6.9 Headache attributed to pituitary apoplexy | 1 | |

| 7.4 Headache attributed to intracranial neoplasm | 1 | |

| 9.2.2 Headache attributed to systemic viral infection | 7 | |

| 10.3.4 Headache attributed to pre-eclampsia or eclampsia | 11 | |

| 11.5 Headache attributed to disorders of the nose or paranasal sinuses | 2 | |

| 11.6 Headache attributed to disorders of the teeth or jaw | 1 | |

| 11.7 Headache attributed to temporomandibular disorder | 2 | |

| Painful cranial neuropathies, 2.1% | 13. Painful cranial neuropathies and other facial pains | 3 |

| Others, 5.6% | 14.1 Headache not elsewhere classified | 8 |

| Appendix, 5.6% | A11, 2.5. Headache attributed to cervical myofascial pain (included for the analysis in the group of secondary etiologies) | 8 |

Regarding risk, we found that 89% of the cases were non-life-threatening conditions (migraine, tension type headache, cervical myofascial, neuralgias/painful neuropathies, temporomandibular joint disorder, systemic infections) and the remaining number were conditions that can result in death (intracranial tumors, intravascular lesions and pre-eclampsia).

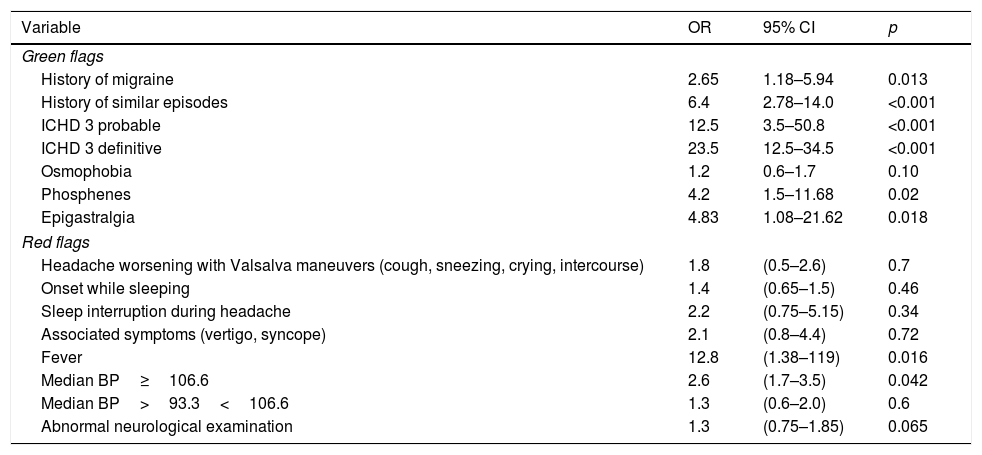

Fever and Blood median pressure over 106.6mmHg were predictors of non-primary headaches. Although immunosuppression was considered as a factor related to non-primary headaches, we did not find cases to be part of this research. On the other hand, a history of migraine, similar episodes of headache, phosphenes, and epigastralgia were more likely in patients whose headache was of primary origin. Regarding the ICHD 3 criteria, the likelihood for primary etiologies was statistically significant even when they were found probable, Table 3. The diagnostic test values for the ICHD 3 criteria were Specificity: 97.1% (95% CI, 95.1–99.1), Sensitivity: 83.4% (95% CI, 73.2–93.6), PPV 95.8% (95% CI, 92.8–98.8) and NPV 87.7% (95% CI, 82.5–92.7).

Green flags and red flags.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green flags | |||

| History of migraine | 2.65 | 1.18–5.94 | 0.013 |

| History of similar episodes | 6.4 | 2.78–14.0 | <0.001 |

| ICHD 3 probable | 12.5 | 3.5–50.8 | <0.001 |

| ICHD 3 definitive | 23.5 | 12.5–34.5 | <0.001 |

| Osmophobia | 1.2 | 0.6–1.7 | 0.10 |

| Phosphenes | 4.2 | 1.5–11.68 | 0.02 |

| Epigastralgia | 4.83 | 1.08–21.62 | 0.018 |

| Red flags | |||

| Headache worsening with Valsalva maneuvers (cough, sneezing, crying, intercourse) | 1.8 | (0.5–2.6) | 0.7 |

| Onset while sleeping | 1.4 | (0.65–1.5) | 0.46 |

| Sleep interruption during headache | 2.2 | (0.75–5.15) | 0.34 |

| Associated symptoms (vertigo, syncope) | 2.1 | (0.8–4.4) | 0.72 |

| Fever | 12.8 | (1.38–119) | 0.016 |

| Median BP≥106.6 | 2.6 | (1.7–3.5) | 0.042 |

| Median BP>93.3<106.6 | 1.3 | (0.6–2.0) | 0.6 |

| Abnormal neurological examination | 1.3 | (0.75–1.85) | 0.065 |

Headache in pregnant women, ICHD: International Headache Criteria. BP: blood pressure.

1 out 20 patients who visits the obstetric emergency room undergoes headache as the main complain. Primary headaches are more frequent than non-primary etiologies being migraine and preeclampsia the most prevalent entities in each group respectively. As expected fever, high blood pressure and abnormalities at the neuro exam presented as predictors of non-primary causes. On the other hand having history of migraine and fulfilling the ICHD criteria for primary etiologies became the most reliable elements to consider this group of headaches. The present clinical-based study showed that the incidence of headache at the emergency department in pregnant women is 4,8%. In spite of the epidemiological differences related to pregnancy this result is in certain extent comparable to the 2.3–3% reported in general emergencies by Knox et al.11

Our study showed that 85% of primary headache cases consulted during the second and third trimester. These results could be explained by the probability that cases in first trimester pregnancy could have been attended at general emergency room due to their unknown condition of pregnancy, modifying the expected proportion of headache etiologies during this period.

In our report the main etiological group was determined by primary headaches with 69% of the cases, this finding is similar with the data reported by Robins et al who found in a similar population that 65% of the cases were part of this group.12 This proportion could be justified by the high prevalence of migraine in the general population, especially in women at reproductive age along with the disability associated to this condition2 which is the main factor leading to consultation at the emergency service. Migraine in our study was the most prevalent primary headache with 61.2% of the cases, this result coincided with the 59.3% reported by Robins et al.12

The low incidence of the other members of the primary group headaches described in this study is justified by the non-debilitating character of TTH and the low prevalence of TACs and group IV headaches in the general population and therefore at the clinical setting.13

Headache is reported in 38.2% of the patients with preeclampsia.14 This percentage could explains why this hypertensive disorder represented the most frequent etiology for secondary headaches in this study 11/28 cases (39,2%) and 11/142 cases of the whole group (7.7%). Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to mention that, according to our results, HBP was only significant when median measure was higher than 106.6mmHg, meaning that headache probably is not a good indicator of preeclampsia when mean blood pressure is abnormal, but lower than this value. This finding probably correlates with the preeclampsia pathophysiology and the severity of endothelial dysfunction along with hemodynamic changes which could be directly related to the likelihood of headache in this patients.15

Taking into account that ICHD 3 criteria were not successfully fulfilled for tension type headache with pericranial tenderness (2.1.1, 2.2.1, 2.3.1) or cervicogenic headache (11.2.1) our study reports that 5.6% fulfilled the criteria for Headache attributed to cervical myofascial (A11.2.5), this finding coincides with a similar series in general emergencies.16 These data give arguments in order to justify the transfer of this entity to the main body of international headache classification.

Following the International Headache Society's criteria, 5.6% of the patients were labeled as unclassified, which is similar to the 6.6% showed in the study by Melhado et al,17 this result is related to the sensitivity and specificity reported in this study, 83.4% and 97.1% respectively, suggesting that the ICHD 3B criteria is reliable when applied in a real clinical setting.

In addition to high median blood pressure, the analysis of predictors for primary vs non-primary etiologies depicted fever in the role of inflammation or infection marker as a predictor of underlying etiologies. This finding, nevertheless, does not represent a high impact factor because, although it has been described in rare primary headaches,18 when present, almost instinctively leads the clinician to look for secondary etiologies. Our analysis failed to demonstrate statistical significance for other potential factors for non-primary headaches such as sleep interruption, associated symptoms (vertigo, syncope and diplopia) and relation to valsalva maneuver, which were present in similar proportion in both groups. Likewise, in spite of immunosuppression being a clear predictor of secondary etiologies, there was no cases in any group.

With respect to predictors of primary etiologies, fulfilling the ICHD 3 criteria was the most significant factor even in probable cases, this finding could be explained by the multivariable component of this tool.

In this part of the analysis we hypothesize that the number of episodes (criteria A) along with the duration of the pain (criteria B) represent the factors in the emergency setting with the highest specificity and sensitivity to establish a difference between primary vs non-primary headaches. On the other hand, we believe that criteria C, characteristics of the pain and D, nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia are non-specific nor sensitive because, although they are useful at the outpatient setting19 they could be present in several medical conditions in which headache is present, regardless if the origin is primary or secondary. Although osmophobia has been described in 74–8420 of migranous patients we were not able to find statistical significance in this group, this finding could be explained by the physiological changes during pregnancy which can increase the prevalence of this symptom during this period.

This study shows the practicality of using clinical tools as an indicator of when to consider further studies for the clinical approach of pregnant women complaining of headache, stablishing additional factors and integrating these results to models of probability models could be the hypothetical base for future research.

The main strengths of this study are using the triage as the primary source of information, along with the application of the ICHD3 criteria, which allow certainty in the type of diagnosis and its real proportion in the reported casuistry. This statement is supported as well by the prospective design of this study.

Some of the limitations of this research are related to the high proportion of migraine patients, meaning that the high likelihood of the ICHD criteria to predict a primary etiology are in some extent more applicable for migraine than for the general group of primary headaches. It is worthwhile to mention that this study did not consider analysis related to the headache frequency. One additional weakness of this study is associated with the fact that the ICHD3 components were not statistically assessed individually. However, in the clinical practice they are applied as a group. Having differences between every component would bring about relevant information which could derive in further hypothesis.

ConclusionIn the absence of reliable and practical biological markers the International Headache criteria along with clinical signs becomes a useful tool in order to diagnose and classify headache syndromes at the obstetric emergency room.

FundingUnidad de Neurología, Hospital MÉDERI.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

To the patients who participated in this study.