Canada’s healthcare system has gained great support in the country, but at the same time has sparked a big debate over its main challenges and sustainability. This article weighs both positive and negative aspects of the healthcare system, known as Medicare. It has three sections: the first presents a theoretical framework based on the political economy of healthcare, and a historical context, where the origins of Medicare are addressed. The second part assesses Medicare’s main achievements, and the third analyzes the system’s main challenges.

El sistema de salud de Canadá ha ganado gran apoyo en el país, pero al mismo tiempo ha desatado un gran debate respecto a sus principales retos y sustentabilidad. Este artículo pondera tanto los aspectos positivos como los negativos del sistema de salud conocido como Medicare. Consta de tres secciones: la primera presenta un marco teórico basado en la economía política del sistema de salud y un contexto histórico en el que se presentan los orígenes de Medicare; la segunda parte evalúa sus principales logros, y la tercera analiza los principales retos que enfrenta el sistema. Para terminar se presentan conclusiones y perspectivas.

Healthcare is one of the pillars of development. If Canada is compared with other highly industrialized countries, such as Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (oecd) members, it devotes a high percentage of its gdp to this sector. In Canada, as stated by Neil Stuart and Jim Adams (2007), a historical debate has taken place about the healthcare system’s sustainability; since the beginning, this debate has mostly been public and has become intertwined with opposing ideological positions on how the system should be financed and delivered. The right argues that healthcare costs have increased so much that reforms are needed, saying that privatization of some services is a solution so that patients can pay for their own care. The left, on the other hand, argues that the system is still sustainable and praises the history of a long-standing commitment to universal coverage (Stuart and Adams, 2007). Thus, the debate about the healthcare system has been ideological. The main goal of this article is to go beyond that, to present the main characteristics of the Canadian healthcare system, and to weigh its achievements and challenges from the mid-1990s until 2015. Likewise, it envisages perspectives for the system’s evolution.

State of the Art and Gaps in the LiteratureIn both the academic and non-academic literature related to the Canadian healthcare system, multiple voices support or criticize it. The government’s Health Canada shows positive information on the system, stressing the high percentage of healthcare that is publicly funded (Health Canada, 2016). Authors like Aaron E. Carroll (2012) and Sara Robinson (2008) defend the system against negative myths. On the other hand, organizations like The Commonwealth Fund compare Canada’s healthcare system to those of other industrialized countries, stressing its challenges. None of the analyses in these publications show any grey areas. A few exceptions to the rule exist, like Gregory Marchildon (2013), who offers a comprehensive assessment of Canada’s healthcare system, touching on both positive and negative aspects. The author presents historical information up to 2011, but his work needs to be updated. A similar case is the article written by Stephen Birch and Amiram Gafni (2005), “Achievements and Challenges of Medicare in Canada: Are We There Yet? Are We on Course?” These authors agree that a positive aspect of the Canadian healthcare system is the fact that public funding supports the provision of healthcare services free at the point of delivery, which is associated with increases in the proportional share of services used by the poor and in population distributions of services independent of income. The challenge they address is that services are distributed in accordance with need; and the objective of needs-based access to services remains elusive. Again, this article should be updated, as it was published in 2005. Toba Bryant (2006), David Coburn (2006), and Mary E. Wiktorowicz (2006) present critical theoretical approaches.

This article offers a theoretical stance, a historical analysis, and up-to-date information, and attempts to fill a gap in the literature on the Canadian healthcare system by presenting both positive aspects as well as areas where it could be improved.

The article is structured as follows: a first section presents a theoretical framework, based on political economy applied to health, and a historical context, addressing the origins of the Canadian healthcare system. The second part assesses Medicare’s main achievements. Here the reader will find an explanation of how the system is financed, organized, and regulated. Basic information on both the public and private system will be analyzed and special attention paid to the evolution of healthcare expenditures, both as a percentage of gdp and per capita, from 1975 to 2015. The third part evaluates Medicare’s main challenges: 1) geographical gaps that translate into social and health gaps; 2) limitations in public coverage that make private services costly; 3) the aging population and its consequence on the health budget; and, 4) the big problems caused by wait times. Conclusions and perspectives for the healthcare system follow.

Theoretical Stance and Historical ContextTheoretical Stance: The Political Economy of Healthcare Applied to the Canadian CaseIn theoretical terms, the Canadian healthcare system can be analyzed through the premises of political economy, which examines “the power relations, which mutually constitute the production, distribution, and consumption of resources” (Mosco, 2009: 2). This article evaluates how the Canadian healthcare system produces, distributes, and consumes health resources. The next section will explain the system’s organizational design, that is, its modes of financing and delivering services.

National healthcare systems are organized on three planes: 1) financing: how services are paid for, publicly or privately; 2) delivery: how services are delivered: publicly or privately; and, 3) allocation: how funds are allocated to service providers (Wiktorowicz, 2006: 247). One of the positive aspects of the Canadian system is that it is a single-payer system, in which 70 percent is financed with public funds. Wiktorowicz considers that “in a publicly funded healthcare system, all citizens contribute to and pay for the system of health insurance through their personal income and taxes. Important advantages include: 1) spreading the risk of illness across the entire population so that insurance is affordable to all citizens, even those with greater risk of falling ill; 2) more effective cost control over health care services; and, 3) universal coverage” (Wiktorowicz, 2006: 247). For analyzing Canadian healthcare, it is natural to contrast it to its neighbor’s, since healthcare in the United States is based on a system of private insurance. These differences are embedded in different ideological premises and political authority, as expressed by Wiktorowicz: “At the close of the twentieth century, Canada and the United States reflected diverging patterns in the organization and delivery of their healthcare systems. Each nation’s healthcare system was founded on different ideological premises and political authority, and these same forces continue to shape their evolution” (Wiktorowicz, 2006: 241-242). Apart from these differences, the two countries also have different perspectives for the healthcare system’s development and reform, and consequently debates about this are highly politicized. “These debates are based on different opinions about the role of government in health care, which arise from different values and national traditions” (Wiktorowicz, 2006: 242). These differences have arisen throughout history in Canada. As the next sub-section on the origins of Canada’s healthcare system explains in more detail, the founder of Medicare was and continues to be a very respected and popular Canadian, Tommy Douglas. He created full health coverage in his province, Saskatchewan, and this model was then expanded nationwide. As Coburn writes, “In Canada, the formation of a socialist or social democratic party, which attained power in Saskatchewan at the end of the Second World War, was crucial. This party first introduced hospital insurance, and later health insurance for hospital and doctor care. This example haunted the federal government and the other provinces. Pressure from various sources —many but not all of these originating with working-class movements— eventually led to its enactment on the federal level” (2006: 76).

Nevertheless, this welfare state policy has not been supported during the whole twentieth century. As Bryant explained, “Within the typology of welfare states, there is room for national variation. Both global and national political, economic, and social forces influence public policy and the shape of the welfare state in Canada. Within the Canadian system, these dynamics include political ideologies of the government of the day and competing interests. The rise of neo-liberalism has influenced welfare state policies in Canada” (Bryant, 2006: 203). The rise of neo-liberalism in Canada could be perceived especially during the 1990s. Bryant, citing Scarth (2004), states, The rise of neo-liberalism in liberal political economies (for example, Thatcherism in the United Kingdom; Reaganism in the United States; and Mulroneyism in Canada) has created increased income inequalities and the weakening of social provision. Certainly, policies followed by Finance Minister Paul Martin during the 1990s reflect both a neo-liberal approach and a distinct threat to the Canadian welfare state. (2006, p. 204)

These inequalities and weak social provisions will be assessed in section three of this article, which addresses the drawbacks of the Canadian healthcare system. This article will also make comparisons with other industrialized countries. It is important to note, then, that under neoliberalism, countries increase their level of inequalities. As Coburn writes, In the developed nations the onset of neo-liberalism has been associated with increasing within-nation inequalities. Increases in inequality have been particularly pronounced in those nations adopting more stringent neo-liberal or market-oriented politics and policies. In the early 1990s the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom stood at the top of the income inequality ladder, while Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands were the lowest (although by 1994 Canada had moved more toward the middle). (2006: 69-70)

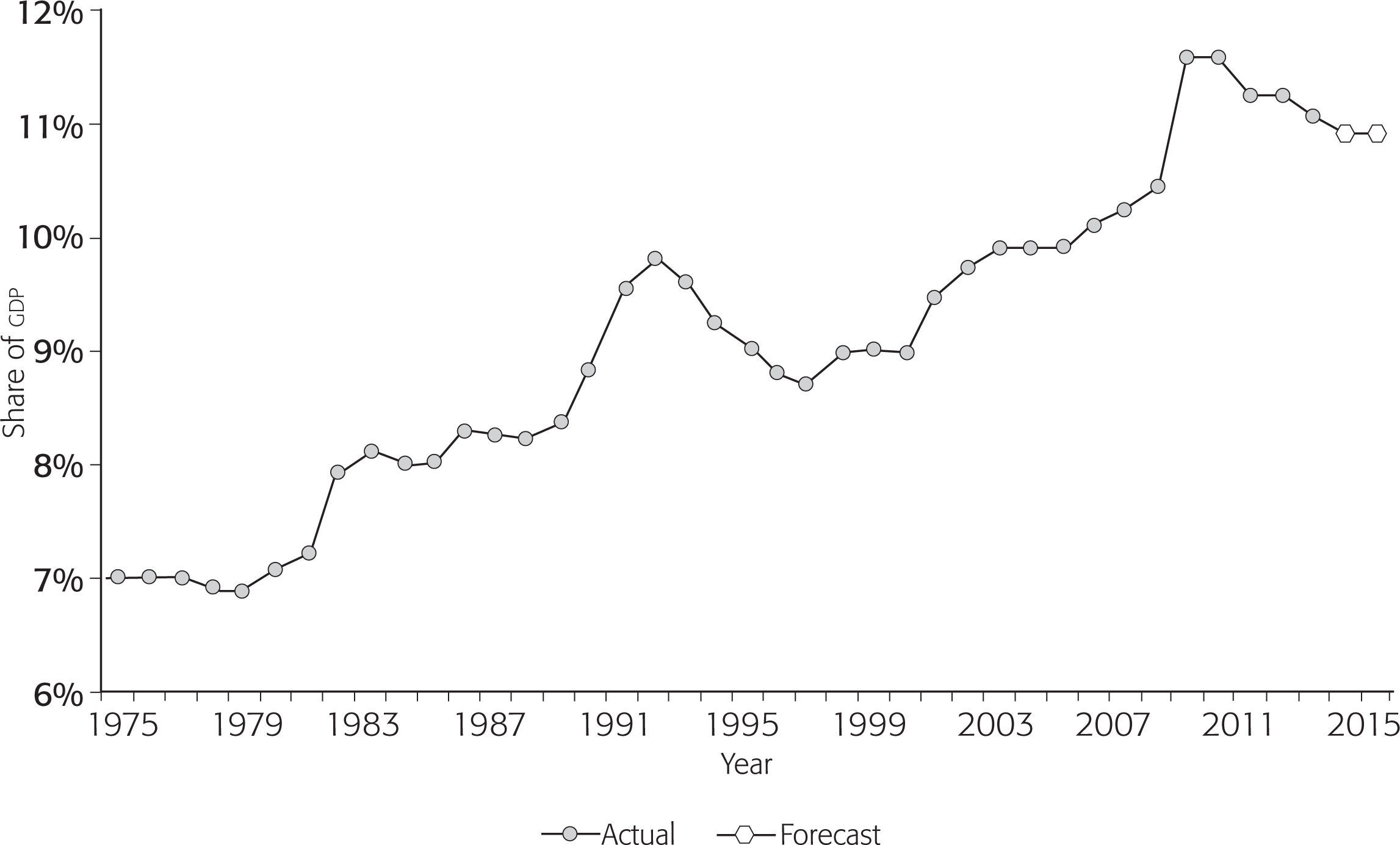

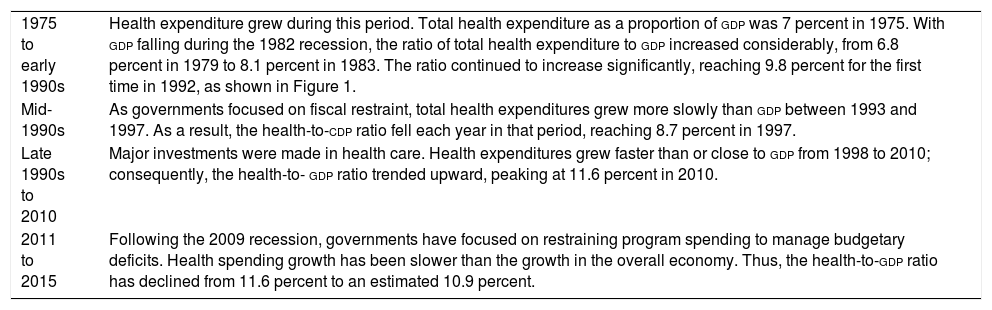

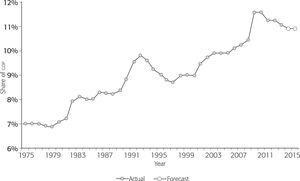

Table 2 shows that in the mid-1990s, “as governments focused on fiscal restraint, total health expenditures grew more slowly than gdp between 1993 and 1997. As a result, the health-to-gdp ratio fell each year in that period, reaching 8.7 percent in 1997” (cihi, 2015: 7). The fall in healthcare expenditures during the 1990s was caused by the economic recession in the country from 1989 to 1992. During that time, the deficit caused cuts in social expenditure. Another recession that caused healthcare expenditure cuts occurred in 2009. Following that economic crisis, the government focused on restraining programs. Health spending growth has been slower than the growth in the overall economy. Figure 1 illustrates cuts in healthcare expenditures during the 1990s, when neoliberal policies were applied, and also following the 2009 crisis.

Evolution of Canadian Health Expenditure as a Percentage of gdp (1975 to 2015)

| 1975 to early 1990s | Health expenditure grew during this period. Total health expenditure as a proportion of gdp was 7 percent in 1975. With gdp falling during the 1982 recession, the ratio of total health expenditure to gdp increased considerably, from 6.8 percent in 1979 to 8.1 percent in 1983. The ratio continued to increase significantly, reaching 9.8 percent for the first time in 1992, as shown in Figure 1. |

| Mid-1990s | As governments focused on fiscal restraint, total health expenditures grew more slowly than gdp between 1993 and 1997. As a result, the health-to-cdp ratio fell each year in that period, reaching 8.7 percent in 1997. |

| Late 1990s to 2010 | Major investments were made in health care. Health expenditures grew faster than or close to gdp from 1998 to 2010; consequently, the health-to- gdp ratio trended upward, peaking at 11.6 percent in 2010. |

| 2011 to 2015 | Following the 2009 recession, governments have focused on restraining program spending to manage budgetary deficits. Health spending growth has been slower than the growth in the overall economy. Thus, the health-to-gdp ratio has declined from 11.6 percent to an estimated 10.9 percent. |

Source: Developed by the author based on data from cihi (2015: 7).

Although the Canadian healthcare system continues to be mostly public, some internal forces have attempted to make the private percentage bigger. Privatization is one of the main premises of neoliberalism. As Coburn stated in 2006 (78), Today, the push toward privatization ranges everywhere from the commodification of knowledge, including knowledge about health, previously commonly held in universities, to privatization even of specific human gene pools. All of this has profound implications for the provision of healthcare. It is a daily struggle within neoliberalism to preserve any form of collective benefit…. In addition to “real” problems with the delivery of care in Canada under Medicare, it is in the interests of private health interests to make Canadians dissatisfied with public health care and to create a “crisis.”

The challenges of the Canadian healthcare system, stressed mainly by those who detract from it, were enumerated by Coburn in this short paragraph, where he compares the Canadian and the U.S. American systems: To reduce or avoid waiting lists, to make the system more responsive to patients, and to have a more geographically equal distribution of access. The major challenge in the United States is to get access to care more equally distributed —that is, the problem of health care inequalities (particularly related to income and race)—and the huge administrative and other costs. (2006: 78)

Coburn also analyzes the relationship between welfare regimes and inequalities, writing, Different welfare regimes and rising inequalities of various kinds have important implications for health inequalities. In general, within nations, the higher a group’s socio-economic status (ses), the higher its health status. Within nations, ses differences in health (however measured) are substantial and have been widely reported….In the United States and Canada, infant mortality rates and longevity rates are highly related to geographical region and to race and Aboriginal status….In Canada, First Nations groups show much worse health than do other Canadians. (2006: 71-72)

Section three of this article includes a sub-section dedicated to the analysis of limitations on access to healthcare, in particular due to social and geographical gaps that translate into health gaps. Coburn explains this situation in detail, comparing it to the one in the United States: Though Canadians have fewer financial barriers to access to care, this does not guarantee equality in actual usage. Aboriginal peoples in Canada, those in isolated areas, and the poor receive less adequate or appropriate care than the less isolated and those higher in ses, but nevertheless health care is more equally provided and accessible than in the United States, and more equitably provided than before Medicare. In Canada, the implicit rationing is due to constraints on available personnel and equipment; in the United States, it is rationing by income. (2006: 78-79)

Coburn refers to wait times in Canada as one important drawback of the system, due to the lack of personnel and equipment. In the United States, on the other hand, there are more investments in these assets, but care is less affordable (2006: 78-79).

For the future, the question is whether Justin Trudeau’s current Liberal Party administration, traditionally left-of-center, will improve the Canadian healthcare system. There may be hope according to Bryant’s analysis: Canada has a relatively weak welfare state as compared to other nations, and even this state is under threat. What do we know about the determinants of a strong welfare state that can assist those wishing to resist these threats and strengthen public policy in the service of health? The influence of “left political parties” is important to the development of the welfare state and its maintenance in the post-industrial capitalist era. These parties support redistribution of wealth and advocate for universal social and health programs. (2006: 204)

The Canadian healthcare system, known as Medicare, has its origins in Saskatchewan Premier and Minister of Health Tommy Douglas’s promotion of it in his province. Only three months after being elected, in July 1944, the Douglas government provided total health coverage in the province for treating mental diseases, sexually transmitted diseases, and cancer. On January 1, 1945, his government went beyond that and provided cards for accessing full health coverage, including medications, to all pensioners, mothers, and disabled individuals from Saskatchewan. In 1945, the first Medicare program was established in the poorest region of that province, granting full coverage for medical, hospital, and dental services. In 1961, the Douglas government introduced an act to implement total Medicare coverage for every Saskatchewan resident, which came into full effect in July 1962 (Saskatchewan New Democrats, 2008).

In 1961, Justice Emmett Hall, also from Saskatchewan, was entrusted with carrying out a Royal Commission on Medicare. The commission wrote a report that became the basis for the Medicare system for all of Canada, based on the Saskatchewan experience. Then, Canada’s Parliament approved the Medical Care Act of 1966, known as Medicare, which guarantees access for all legal residents of the country’s 10 provinces and 3 territories. Universal coverage, according to this law, is based on need, not on the ability to pay for a service (Hailey, 2007; Health Canada, 2014; Canadian Museum of History, 2014). However, in practice, as will be explained below when analyzing the system’s challenges, certain services are not covered by Medicare, which can be very costly for Canadians. Therefore, on some occasions, high costs can discourage access to health services for individuals who cannot afford them.

Since its creation, the Canadian healthcare system has accrued a number of achievements, but also a series of major challenges. Both will be addressed below. At the end of the article are the conclusions, where positive and negative aspects will be weighed against each other.

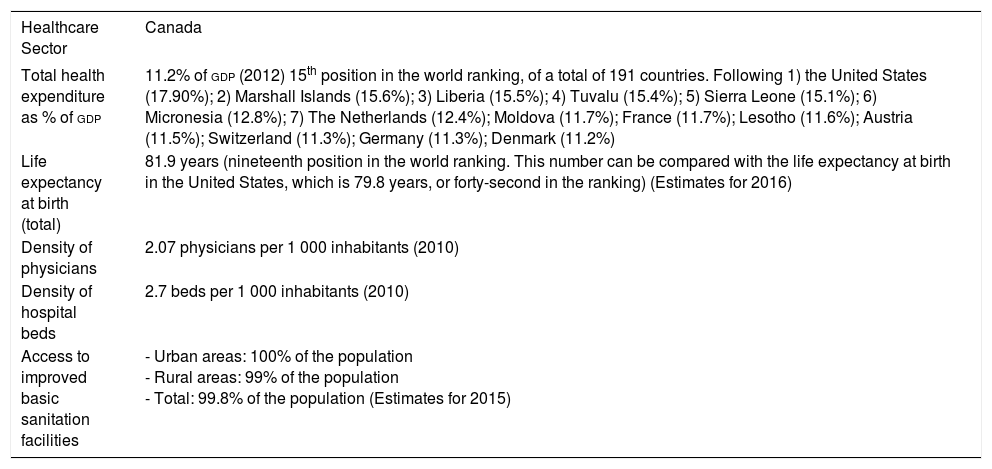

Canadian Healthcare System: Main AchievementsThe first positive aspect worth mentioning is that the total expenditure of the Canadian healthcare sector is relatively high: approximately Can$207 billion in 2012, of which 70 percent was financed with public funds (Health Canada, 2014). If compared with other oecd countries, healthcare expenditure in Canada in 2012 was 10.4 percent of its gdp, putting it among the top 8 of 35 countries, after the United States (17.1 percent), The Netherlands (12.4 percent), France (11.7 percent), Austria (11.5 percent), Switzerland (11.3 percent), Germany (11.3 percent), and Denmark (11.2 percent) (cia, 2016). As Table 1 shows, Canada occupies fifteenth place in the world for health expenditure as a percentage of gdp. Universal coverage is certainly a positive aspect of the system. The Canada Health Act defines insured persons as residents of a province. The act further defines a resident as: “a person lawfully entitled to be or to remain in Canada who makes his home and is ordinarily present in the province, but does not include a tourist, a transient, or a visitor to the province” (Health Canada, 2011a). So, universal coverage includes every resident, not everyone on Canadian soil. Universal coverage is not even affected if a patient loses or changes his/her job. Furthermore, no restrictions or limitations are imposed due to pre-existing conditions. In the United States –just to compare Canada to its neighbor– eliminating pre-existing conditions as a limitation is something new. It was introduced in 2014, after the Affordable Care Act, known as ObamaCare, signed by President Obama on March 23, 2010 (ObamaCare Facts, 2016). Moreover, medication in Canada is covered with public funds for indigenous peoples and senior citizens. The price of the medication is negotiated between governmental authorities and vendors to control costs (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2005: 91). The following table presents relevant data on the Canadian healthcare system.

Indicators for the Canadian Healthcare Sector

| Healthcare Sector | Canada |

|---|---|

| Total health expenditure as % of gdp | 11.2% of gdp (2012) 15th position in the world ranking, of a total of 191 countries. Following 1) the United States (17.90%); 2) Marshall Islands (15.6%); 3) Liberia (15.5%); 4) Tuvalu (15.4%); 5) Sierra Leone (15.1%); 6) Micronesia (12.8%); 7) The Netherlands (12.4%); Moldova (11.7%); France (11.7%); Lesotho (11.6%); Austria (11.5%); Switzerland (11.3%); Germany (11.3%); Denmark (11.2%) |

| Life expectancy at birth (total) | 81.9 years (nineteenth position in the world ranking. This number can be compared with the life expectancy at birth in the United States, which is 79.8 years, or forty-second in the ranking) (Estimates for 2016) |

| Density of physicians | 2.07 physicians per 1 000 inhabitants (2010) |

| Density of hospital beds | 2.7 beds per 1 000 inhabitants (2010) |

| Access to improved basic sanitation facilities | - Urban areas: 100% of the population - Rural areas: 99% of the population - Total: 99.8% of the population (Estimates for 2015) |

Source: Developed by the author based on cia (2016).

Note: According to 2013 estimates, Canada’s gdp was US$1.518 trillion. Canada is fourteenth in the world ranking by gdp. The United States ranks first with US$16.72 trillion.)

Table 1 indicates that the entire urban population has access to improved basic sanitation facilities, as does 99 percent of the rural population.

The data of 2.7 beds/1 000 inhabitants was slightly greater than in the United States, which in 2011 had 2.45 beds/1 000 inhabitants. Canada had 2.07 physicians per 1 000 inhabitants in 2010, while the United States had 2.45 physicians per 1 000 inhabitants in 2011 according to the same source (cia, 2016).

Table 1 also shows that Canada spends a lower percentage of its gdp on healthcare than the United States; however, life expectancy of Canadians is two years higher than that of their southern neighbor. Likewise, Canadian residents’ access to public health has been greater than in the neighboring country. According to data revealed by a survey of Canadians and U.S. Americans in 2006, the latter had at that time less access to a family physician, satisfied their healthcare needs less, and had less access to necessary medications. Disparities according to race, income, and migratory status were present in both cases, but were more pronounced in the United States (Lasser, Himmelstein, and Woolhandler, 2006).

How Is Canada’s Healthcare System Financed, Organized, and Regulated?The healthcare system is 70-percent financed by federal, provincial, and territorial taxes. Most public revenues allocated to healthcare are used to provide universal coverage (hospital and medical services) and to subsidize the cost of medications (Marchildon, 2013: xiii). Additional services are also provided by the provinces and territories to certain people, such as seniors, children and low-income residents, for services not covered by the public healthcare system. Some of these supplementary benefits include prescription drugs outside hospitals, dental care, eye care, medical equipment, and appliances (such as prostheses and wheelchairs), and the services of other health professionals, like physiotherapists. The level of coverage varies across the country. Those who do not qualify for supplementary benefits under government plans can pay for these services out of pocket or through private health insurance plans. Most people are covered through their employers or on their own by private health insurance; the level of coverage varies depending on the plan purchased (Health Canada, 2011b and 2016; Government of Canada, 2014a; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2005). In general, healthcare expenses are covered with income taxes, and some provinces allocate an extra monthly tax to the healthcare sector, from which those with low incomes are exempt; this is the case of British Columbia (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2014).

The administration and organization of healthcare services are highly decentralized. Provinces and territories are responsible for administering healthcare and for planning medical services (Marchildon, 2013: xiii). In order to use healthcare services, a Canadian citizen or resident must present his/her health insurance card in hospitals or clinics. The insurance varies in each province and territory. If a resident of one province travels to another for medical treatment, he or she may not find full coverage. For example, “when traveling outside of Ontario but within Canada, the ministry recommends that you obtain private supplementary health insurance for non-physician/non-hospital services” (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2016c).

The federal healthcare system is regulated by the Canada Health Act of 1984, which guarantees that health services are universal, accessible to every resident and public (Health Canada, 2014). Its objective is “to protect, promote, and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to healthcare services without financial or other barriers” (Government of Canada, 2014a: section 3 of the 1984 Act). This act establishes the criteria and conditions for federal and provincial health services. It also establishes that through the Canada Health Transfer, the government will provide a contribution in cash to the provinces every fiscal year. In order for them to receive their contributions, they must comply with the following criteria: a) public administration; b) comprehensiveness; c) universality; d) portability; and e) accessibility (Government of Canada, 2014a, sections 4-7 of the 1984 Act).

Evolution of Healthcare Expenditure in CanadaIt is good news to know that healthcare expenditures in Canada have risen from 1975 to 2015. Nevertheless, there have been periods of recession, such as the mid-1990s and after the 2009 financial crisis, whose effects were felt in 2011.

Table 2 gives details on health expenditures during four phases: 1) 1975 to the early-1990s; 2) the mid-1990s; 3) the late 1990s to 2010; and, 4) 2010 to 2015.

The information provided in Table 2 is graphically represented in Figure 1, below.

As explained in Table 2, the fall in healthcare expenditures during the 1990s can be explained by the recession the country experienced from 1989 to 1992. During that time, the deficit caused a cut in social expenditure. In the 1990s, the number of nurses and hospital staff was reduced, spurring physicians to emigrate to the United States. At that time, provincial commissions were created to propose a restructuring of the healthcare sector. Likewise, the press contributed to spreading the population’s concerns by publishing stories of people who had not been covered by the public sector, pointing out, furthermore, the growing conflict between Ottawa and the provinces, in particular Alberta, Ontario, and British Columbia (Canadian Museum of History, 2014).

During the 1993 federal election campaign, the Liberal Party promised to renew its commitment to Medicare. During the 1994-1997 government of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, the National Health Forum was organized by both federal and provincial ministers of health. One of the problems detected was the absence of information on the quantity and the type of services available, the requirements of human and material resources, and the costs generated by the healthcare sector. To deal with this, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (cihi) was created, which has since produced annual reports on healthcare issues (Canadian Museum of History, 2014).

In the beginning of the twenty-first century, public opinion was divided between those who supported Medicare and its detractors. In the polls, healthcare issues have been highlighted as Canadians’ main concern (Canadian Museum of History, 2014). In 2004, the Decennial Action Plan for Improving Health Care established as priorities providing public coverage for home and end-of-life care and reducing wait times. Likewise, in 2005, the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network was created to establish a solid federal and provincial structure to deal with public healthcare emergencies as well as chronic diseases (ops, 2012).

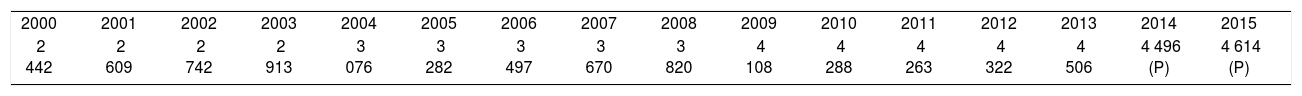

From 2006 to 2010, Canada experienced an economic recession that has presented challenges (ops, 2012) that will be addressed in the next section. Nevertheless, Table 3 shows that during those years per capita health expenditures continued to rise.

Canada’s Health Expenditures (per Capita, Current Prices, Current PPPS) (2000-2015) (US Dollars)

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| 2 442 | 2 609 | 2 742 | 2 913 | 3 076 | 3 282 | 3 497 | 3 670 | 3 820 | 4 108 | 4 288 | 4 263 | 4 322 | 4 506 | 4 496 (P) | 4 614 (P) |

Source: Developed by the author based on data from the oecd (2016).

Nota: (P) = Provisional data.

Table 3 shows that there has been an uninterrupted increase in health expenditure per capita from 2000 to 2015 (oecd, 2016), except for during the 2009 recession. The cihi presented more recent figures in October 2015, which show even higher numbers. According to this source, health spending in Canada in 2015 was projected to reach Can$219.1 billion, representing 10.9 percent of Canada’s gdp in 2015. This amounts to Can$6 105 per Canadian, compared to projections presented in Table 3, of just Can$4614 per capita.

According to cihi, among 29 countries with comparable accounting systems in the oecd in 2013, expenditure per person on healthcare was the highest in the United States (US$9 086). Canada was in the top quartile of countries in terms of per-person spending on health, at US$4 569; this was less than Denmark (US$4 847) and more than France (US$4 361), Australia (US$4 115) and the United Kingdom (US$3 364) (cihi, 2015).

To sum up, the main achievements of the Canadian healthcare system, from its creation until 2015, have been 1) the relatively high expenditure, both as a percentage of gdp and per capita, if compared with other oecd countries; 2) the fact that 70 percent of the system is publicly financed; 3) services are highly decentralized, making provinces and territories responsible for administering healthcare and planning medical services; 4) the system is regulated by the Canada Health Act of 1984, which guarantees that health services are universal, accessible to every resident, and public.

The Canadian healthcare system definitely has a series of advantages. But it is not perfect. Below is an analysis of the major challenges it faces.

Canada’s Healthcare System: Main ChallengesIn addition to the lack of total coverage and the high cost of care not provided by physicians in hospitals, such as dental and psychological services or home care, other challenges faced by the healthcare system can be listed. The Pan-American Health Organization (paho) has identified the following: the aging of the population and the corresponding need to assign more resources to elders; care for chronic and mental diseases as well as for addictions; the need for dealing with social and regional inequalities; the high cost of new technologies; and reducing care times (ops, 2012). What follows is an analysis of some of the main challenges that the system is facing.

Limitations to Access to Healthcare: Geographical and Health GapsAccess to healthcare is a strategic matter for Canadian populations in rural areas, away from the major urban centers,1 in particular for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. Therefore, the guarantee of this right is of utmost relevance given that Canada is the second largest country in the world, and it has very large inhabited areas. Its surface area is 9 984 670 km2, with a population of 35 362 905, according to July 2016 estimates, of which a vast majority lives in a strip 300 km from the U.S. border. Likewise, according to 2015 data, 81.8 percent of the total population of the country lives in urban areas (cia, 2016).

This geographical disparity also translates into health gaps. According to the paho, although the situation of the First Nations, the Métis, and the Inuit has improved in the last few years, they are still behind compared to urban populations. One indicator is life expectancy at birth, which in 2009 was 80.7 years for all of Canada, while for the First Nations it was 72.9 years, and for Inuit, 66.9 years (ops, 2012). According to cia World Factbook estimates for 2016, life expectancy at birth for the total population is 81.9 years (79.2 for males and 84.6 years for women) (cia, 2016).

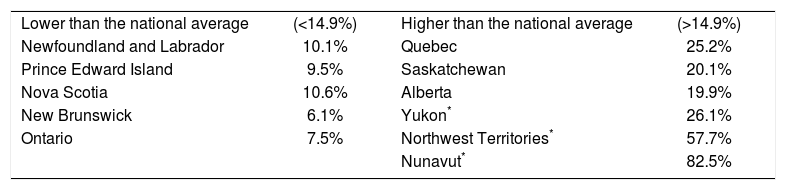

Another gap in provinces and territories is access to a personal doctor. In every province or territory, patients see family physicians of their choice, and they claim their fees with the provincial insurance; patients do not have to go through bureaucratic procedures. If they want to see a specialist, they will be referred by the family physician (cihi, 2005). But generalized access to a regular medical doctor is not equal as it depends on where people live. For many citizens, the first contact for healthcare is their doctor, and being without a regular medical doctor correlates to fewer visits to general practitioners or specialists, who can prescribe early screenings or treatment of medical conditions. In 2014, 14.9 percent of Canadians aged 12 and older (around 4.5 million people) said that they did not have a regular medical doctor. Table 4 shows the percentage of Canadians without a regular doctor by province and territory in 2014 (Statistics Canada, 2015). The first column indicates the provinces where the proportion of residents without a regular doctor was lower than the national average (14.9 percent). The third column lists the provinces where the proportion of residents without a regular doctor was higher than the national average.

Canadians without a Regular Doctor by Province and Territory (2014)

| Lower than the national average | (<14.9%) | Higher than the national average | (>14.9%) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 10.1% | Quebec | 25.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | 9.5% | Saskatchewan | 20.1% |

| Nova Scotia | 10.6% | Alberta | 19.9% |

| New Brunswick | 6.1% | Yukon* | 26.1% |

| Ontario | 7.5% | Northwest Territories* | 57.7% |

| Nunavut* | 82.5% |

Source: Developed by the author based on Statistics Canada (2015).

Table 4 shows that the proportion of residents who did not have access to a regular doctor was lower than the national average (14.9 percent) in Newfoundland and Labrador (10.1 percent), Prince Edward Island (9.5 percent), Nova Scotia (10.6 percent), New Brunswick (6.1 percent), and Ontario (7.5 percent). The proportion of residents who were without a regular doctor was higher than the national average in Quebec (25.2 percent), Saskatchewan (20.1 percent), Alberta (19.9 percent), Yukon (26.1 percent), Northwest Territories (57.7 percent), and Nunavut (82.5 percent). Residents of Manitoba and British Columbia reported rates similar to the national average (Statistics Canada, 2015).

In 2014, of the 4.5 million people without a regular doctor, the most common reason for this was that they had not looked for one (45.9 percent). Other reasons were that doctors in their area were not taking new patients (21.5 percent), their doctor had retired or left the area (20.2 percent), or that no doctors were available in their area (14.4 percent). Another 13.1 percent did not give a specific reason.2 But of the 4.5 million Canadians without a regular doctor in 2014, 81.5 percent said they had a usual place to access the healthcare system. If they needed medical care, 59.1 percent reported they would use a walk-in clinic, 14.2 percent would use a hospital emergency room, and 8.6 percent would visit a community health center (in Quebec this is known as a centre local de services communautaires). The remaining 18.1 percent said they would use other facilities such as appointment clinics, doctors’ offices, hospital outpatient clinics, and telephone health lines (Statistics Canada, 2015). These figures denote that most Canadians in urban areas have access to a regular doctor, and if they do not, they have other options to look for healthcare. Nevertheless, the system is still uneven as there is a big difference in access to healthcare in the territories.

Limitations to Public Coverage: Private Coverage Can Be ExpensiveAnother disadvantage of the Canadian healthcare system is that Medicare does not cover all medical services. Likewise, healthcare depends on where the patient is being treated —in a hospital or not— and what province he/she lives in. For a province to receive federal funds for healthcare programs, it must comply with the basic requirements stipulated in the Canadian Healthcare Act, which include the “necessary medical attention” in healthcare matters. However, this concept is not defined; it is discretional and up to free interpretation by each province, including hospital care and the care given by family physicians. On the other hand, some services not covered by the public healthcare system actually should be considered necessary and therefore be covered. Dental and psychological services as well as home care are cases in point (cfhi, 2011).

Hospital care absorbs around 30 percent of healthcare sector spending and this percentage is decreasing. Medical services provided by health professionals who are not physicians in general take place outside hospitals. Dental services are an example of this: 94 percent are covered directly by patients or by private insurance companies. Oral health, then, is related to the possibility of being able to afford it and not to the need for medical attention. Many Canadians cannot afford this service and sometimes their condition worsens and they have to resort to dental emergencies in hospitals, where they only receive antibiotics and painkillers that do not treat the underlying issue. Furthermore, if the situation becomes more serious, the risk is that the patient must be admitted in a hospital, and the costs are absorbed by the public service (cfhi, 2011). This is an example of how healthcare outside hospitals, provided by non-medical professionals, is available only for those who can afford it and is not based on prevention, but rather on repairing the damage.

As for the access to prescribed medications, each province decides to what extent patients will be covered by the public system. In general, throughout Canada, around 40 percent of these medications are covered by the state and the remainder must be absorbed by private companies or by the patient him- or herself. This payment varies widely among provinces. For instance, an individual who has to pay Can$20 000 annually in medication will not pay anything in the Northern territories; that is, he/she will be fully subsidized. In the province of Quebec, he/she will only pay around Can$1 500; Can$8 000 in Saskatchewan; and Can$20 000 in Prince Edward Island (cfhi, 2011). Again, here we can see another disparity among provinces and territories.

A Major Challenge: Aging of the PopulationWe can foresee that healthcare sector expenses as a percentage of gdp will continue to increase for the next few decades. This is because the Canadian population is aging, and changes in public policies will be needed as a result. This aging trend is due to decreasing fertility rates and increasing life expectancy. In 1971, only 8 percent of the population was made up of people over 65; this figure increased to 14 percent in 2011, and it is still expected to increase up to 36 percent by 2036 (Echenberg, Gauthier, and Leonard, 2011).

The federal government finances pensions for elders (Old Age Security, or oas) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (gis) for low-income people over 65 years of age. In 2009, the oas cost Can$27.1 billion, and gis benefits, Can$7.7 billion. Due to the aging of the population, oas and gis payments are expected to quadruple between 2009 and 2036. The employer pays the Canadian Pension Plan (cpp) to the employee. The employer-employee contributions rate increased from 3.6 percent in 1986 to 9.9 percent in 2003. In order for the program to be maintained, between 2011 and 2016 reforms have been planned to encourage older employees to continue working. For instance, the penalty for retiring at 60 —instead of 65, which is the usual age— will increase from 30 percent to 36 percent, while the bonus for retiring at 70 will increase from 30 percent to 42 percent (Echenberg, Gauthier, and Leonard, 2011).

In 2011, people over 65 accounted for 14 percent of the population, but they were assigned around 44 percent of annual healthcare expenditures, both federal and provincial. Total spending on the Canadian healthcare sector exceeded Can$191 billion in 2010. Federal and provincial government expenditures together have grown faster than the economy, increasing from 5 percent of GDP in 1975 to 7 percent in 2010. Given the aging of the population, by 2036, healthcare sector spending is expected to be between 9 and 12 percent of gdp. Patient demand will increase in areas that are not always provided universal coverage, such as medications, long-term care, home care and end-of-life care. Responding to these demands will depend on economic growth, on innovations in more efficient provision of healthcare services, on the health of people over 65, on the result of the negotiations on coverage, on tax collection and on the financing/indebtedness ratio. As for the care given to patients in their homes, according to 2011 data, one out of every four Canadian employees takes care of a dependent elder at home. Seventy-five percent of those employees are middle-aged women. In the future, the increase in expenses and the decline in hours worked could represent financial problems (Echenberg, Gauthier, and Leonard, 2011).

Great Dissatisfaction over Wait TimesDissatisfaction over the wait times has been recurrent during the last decade. In 2006, Dr. Brian Day was quoted in a New York Times article, saying, “This is a country where dogs can access a hip replacement in one week, but humans must wait between two and three years” (Krauss, 2006). In 2004, the government signed an agreement with the provinces to allocate a total of Can$5.5 billion for reducing wait times. The agreement mentions, for instance, the goal of reducing the wait time for a hip replacement to 26 weeks (104 days) (cbc News, 2006).

In April 2007, former Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that the provinces and territories would have their wait times guaranteed by 2010 for the following areas, which would be prioritized by the provinces: cancer, hip and knee replacement, heart problems, diagnosis and imaging, cataract surgery, and primary care (Nation Talk, 2007). By the beginning of the Justin Trudeau government, this goal had not yet been met.

For the last few years, provincial Ministries of Health have published the wait times for receiving care in emergency rooms and by specialists on their web sites. For instance, Ontario’s Ministry of Health offers web surfers a list of wait times for emergency rooms, surgeries, magnetic resonance imaging, and computing tomography. When doing a search on March 24, 2014, to find out how long a patient would have to wait to get hip replacement surgery, selecting Alexandra Hospital, the system gave the following result: the wait time was 205 days (Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2016a). This wait time was longer than the 104-day goal set by Stephen Harper in 2007. After repeating the same search on the same website on September 30, 2016 for the same hip replacement surgery at the same hospital, the result was 209 days and the target announced increased to 182 days (Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2016a; 2016b). In two and a half years, wait times had remained almost the same, but they were still high. Moreover, they continue to be higher than the projected target.

Likewise, according to 2013 data from the Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey, Canada had the longest wait times for seeing a family doctor of the 11 developed countries in the oecd: Australia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The survey indicates that only between 31 percent and 46 percent of Canadians, depending on the province where they live, can see a doctor on the same day or on the day after the request, when it is not an emergency. The highest percentages in other developed countries were 48 percent in the United States, 76 percent in Germany and 72 percent in New Zealand (cbc News, 2014).

In summary, the major challenges faced by the Canadian healthcare system analyzed above are 1) geographical and health disparities among provinces and territories; 2) the high cost of procedures not covered by the public system, such as oral health; 3) aging of the population and consequently the need to increase health expenditure in the near future; and, 4) wait times. In other publications it will be interesting to continue assessing other major challenges detected by the paho in 2012: care for chronic and mental diseases as well as for addictions and the need to reduce the high cost of new technologies.

In the conclusions, I will weigh the achievements and challenges as well as assess how the healthcare system will evolve.

ConclusionsThe Canadian healthcare system has had achievements since 1994, and it also still faces challenges.

Outstanding among the advances is the evolution of healthcare spending as a percentage of gdp, which has been increasing since 1975, except during the 1989-1992 recession. Future perspectives indicate that the Canadian government will continue increasing this percentage. It is significant that 70 percent of the Canadian healthcare system is public. Another of its advantages is that services are highly decentralized, making provinces and territories responsible for administering healthcare and planning medical services. Moreover, Medicare is regulated by the Canada Health Act of 1984, which guarantees that health services are universal, accessible to every resident, and public.

Despite these achievements, significant challenges also exist. First, Medicare does not cover all medical services. Care provided by health professionals who are not physicians, such as dental and psychological services, are excluded. These can be very costly, depending on the province of residence. Likewise, a current challenge that will be an enormous test in the future is the aging of the population and the consequences this entails for the healthcare and pension system. On the other hand, the wait time for a Canadian to be treated by the public system is the worst among oecd countries. Last, but not least, Canada needs to improve access to healthcare services and address the existing social gap between the urban, rural, and aboriginal populations.

In the near future, it will be necessary to assess whether the electronic records that have been introduced at the federal and provincial levels to control medication costs have been effective. Furthermore, follow-up is needed on care given to aboriginal and other rural communities, which are currently lagging behind compared to the system as a whole. A major challenge, identified by paho in 2012, which will definitely continue to pose a big challenge for the Canadian healthcare system is the incidence of chronic and mental diseases. In further publications, attention should be devoted to assessing care of diabetes, obesity, and overweight. Other challenges for the system will be coping with addictions and the need to reduce the high cost of new technologies.

It remains to be seen whether the Canadian government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will prioritize some of the challenges facing the Canadian healthcare system: prevention and promotion of healthcare, combatting obesity in children and in adults, and cardiovascular problems, diabetes, and other chronic diseases (Canadian Museum of History, 2014). It is yet unknown if Trudeau, who belongs to the Liberal Party, traditionally left-of-center, will enhance the healthcare system. We should remember that, in theory, as Bryant pointed out (2006: 204), “The influence of ‘left political parties’ is important to the development of the welfare state and its maintenance in the post-industrial capitalist era. These parties support redistribution of wealth and advocate for universal social and health programs.” If we weigh achievements and challenges of the current healthcare system, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau definitely has some big tests ahead of him. If he passes them, then he will certainly gain popularity among Canadians.

In 1984 the principle of accessibility was added to the four main principles of the 1966 Medical Care Act in order to guarantee Canadians access to necessary medical services (Canadian Museum of History, 2014).

It is important to note that these add up to more than 100 percent because respondents could choose more than one reason for not having a regular doctor.