This work analyzes Dreamers’ political participation as a civic association movement, as well as their pathway for social change in the U.S. The article reflects on their social capital and the challenges facing them to explain the possible scenarios for a movement that has politicized a considerable number of contemporary young U.S. Americans. The aim is to complement the existing work in the field, contributing with explanations grounded in political sociology approaches, focused on the politicization of undocumented youth, the analysis of minority association, the influence and leadership of the movement, and, especially, Dreamers’ opportunities and challenges in U.S. politics.

Este trabajo analiza la participación política de los dreamers como movimiento de una asociación cívica, así como su desarrollo en pos de un cambio social en Estados Unidos. El artículo reflexiona sobre su capital social y los retos que enfrentan al explicar los escenarios prospectivos de un movimiento que ha politizado a un número considerable de jóvenes estadunidenses contemporaneos. El objetivo es complementar los estudios existentes en el campo, y así contribuir con explicaciones basadas en aproximaciones de sociología política enfocadas en la politización de la juventud indocumentada, el análisis de la asociación de las minorías, la influencia y el liderazgo del movimiento y, en especial, las oportunidades y retos de los dreamers en el contexto de la política de Estados Unidos.

“Youth and migration” has become a very relevant topic of research. Scholars from different disciplines and theoretical approaches have studied immigration based on structural and demographic factors; but only a few works focus on the politicization of a whole generation of young immigrants, their contemporary impact on the immigration debate, and their prospective leadership for the entire immigrant minority. This article is framed in the emerging field of youth immigrant studies that has been partially developed through very specific and empirical case studies of Dreamers’ organizations, life stories, and narratives.

Why are Dreamers the prospective leaders of the Latino minority in the U.S.? What are their assets and challenges in a country that conceives of politics as negotiation and social change only through organization?

The article is divided into three sections. First, I address how undocumented young immigrants have politicized a considerable sector of U.S. youth through their influence on the migration debate, a central issue on the contemporary U.S. political agenda, and also, in the course of doing that, how they have raised their voices, organized, and participated in politics. In order to explain the origins and emergence of the movement, in the first section I broadly describe the characteristics, demands, and general organization of the Dreamers’ movement.

Second, Dreamers are an association movement; their sophisticated structures and the support of other pro-immigrant, ethnic, and advocacy organizations consolidate their groups as part of civil society, despite their mixing “civil disobedience” actions with smart political strategies. To support this idea, I revisit the foundational theories of the U.S. political tradition, maintaining that association and organization are the key pillars for participation and social change.

Third, I analyze Dreamers’ social capital management to elucidate the current skills, strengths, and opportunities of the movement as a unit. And then, I identify its weaknesses and problems for a better understanding of the Dreamers’ possible future and their prospective ethnic leadership.

Who Are the Dreamers? The Will of the American Dream?Dreamers are named for the dream Act, an acronym for the 2001 Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act. The original bill was first introduced into the Senate by Orrin Hatch (R, Utah) and Richard Durbin (D, Illinois). Their early draft proposed the revocation of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, particularly the section that limited federal or in-state tuition and grants for undocumented students. The bill was subsequently re-introduced in 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011, the best known version being the last. Each time, the bill had bipartisan sponsorship and was even supported by presidential candidate John McCain the first and second time; nonetheless, it never received enough votes to get out of committee.

To be specific, the legislators’ failure to approve any immigration reform, coincided with the introduction of the 2005 Sensenbrenner Law, which links immigrants to terrorism, fines border crossers as well as landlords and employers, eliminates the immigration lottery, and projects building a wall along the Mexican-U.S. border. Additionally, in 2006 alone, massive deportations reached 281 000 (usdhs, 2015). All these events together politicized a whole generation of immigrants and resurrected from the ashes citizen association as the primary mechanism for social change.

From Ferguson (1767) to Lipset (1960), different authors at different times have anticipated that when facing adversity, immigrants might achieve group consciousness and constitute civil society for self-preservation. In 2006, they took to the streets to show their capability of mobilizing others and what Putnam (2001) described as their social capital. During this period, Dreamers were still part of student organizations from state universities and community colleges; others were enthusiastic activists embedded in immigrant collectives, but they still remained isolated and unlinked. Dreamers were young activists conducting community outreach, but the movement had not yet developed its own characteristics.

The trigger of the civil movement was documented by Zimmerman (2012): one symbolic October 12, 2011 (Columbus Day/Dia de la Raza), five undocumented students, leaders of civic associations, wearing robes and gowns, bounced into the Los Angeles Immigration and Customs Office to demand the end of deportation of Dreamers. Although the event did not get coverage from more than the local media and press, the effective communication networks already developed on electronic platforms allowed the news to spread among other organized groups of undocumented students. This incident also achieved the identification of more young immigrants living in the same circumstances, and social networks became the main communication strategy that suddenly created a nationwide dissemination network (and McDevitt Sindorf, 2014).

Nevertheless, the movement achieved national status when President Obama said in 2012, “These are young people who study in our schools. They play in our neighborhoods. They’re friends with our kids and pledge allegiance to our flag, They are Americans in their hearts, minds — in every single way but one: on paper” (White House, 2012). Formerly, he had announced the executive order, a presidential prerogative traditionally used when Congress does not enact a law for an important issue that requires immediate action. During this campaign, Obama stated, We’ve got 11 million people here who we’re not all going to deport. Many of them are our neighbors. Many of them are working in our communities. Many of their children are U.S. citizens. And as we saw with the executive action that I took for dreamers, people who have come here as young children and are American by any other name except for their legal papers, who want to serve this country, often times want to go into the military or start businesses or in other ways contribute — I think the American people overwhelmingly recognize that to pretend like we are going to ship them off is unrealistic and not who we are. (White House, 2015)

The Dreamers are professionals, students, and volunteers in the armed forces who crossed the U.S.-México border when they were still children; some of them were still babies who migrated in their parents’ arms, without any will or responsibility. These young immigrants culturally identify themselves as U.S. Americans; some only speak English and do not know their countries of origin beyond their parents’ stories (Louie 2002). Dreamers grew up with U.S. American values and discovered their legal status in their late teens when facing bureaucracy and lost opportunities due to the lack of documents.

Regarding official requirements, the Department of Homeland Security established the formal criteria for requesting postponement of deportation under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (daca). Migrants can request daca if they

- 1.

Were under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012;

- 2.

Came to the United States before reaching their sixteenth birthday;

- 3.

Have continuously resided in the United States since June 15, 2007, up to the present time;

- 4.

Were physically present in the United States on June 15, 2012, and at the time of making their request for consideration of deferred action with uscis;

- 5.

Entered without inspection before June 15, 2012, or their lawful immigration status expired as of June 15, 2012;

- 6.

Are currently in school, have graduated or obtained a certificate of completion from high school, have obtained a general education development (ged) certificate, or are an honorably discharged veteran of the Coast Guard or Armed Forces of the United States; and

- 7.

Have not been convicted of a felony, significant misdemeanor, three or more other misdemeanors, and do not otherwise pose a threat to national security or public safety (us dhs, 2012).

Under these terms, Passel and Lopez (2012) estimated that about 1.7 million immigrants would benefit from daca; only 55 percent were eligible immediately. Deferred action for deportation was announced on June, 2012 and consists of an executive order for two years (renewable) to protect the migrant from deportation. Later, in 2014 Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (dapa) was launched, a three year renewable status to protect U.S. citizens’ parents from deportation. Despite the lack of any migration status, and the absence of civil and politic rights, Dreamers view daca and dapa as victories of their movement based on civic association, not a merely un-structured or disorganized mass movement (Abraham, 2015).

Through creative and innovative slogans like “Undocumented and Unafraid” and e.n.d. (“Education No Deportation”), Dreamers’ organizations caught the attention of the U.S. media and reached out for the empathy of U.S. society. The wise use of social media also connected them to youth in the same circumstances, and together Dreamers associated against discrimination and limitations. It is noteworthy that these young immigrants reject the term “Dreamers”; they say their demands are realistic and that they did not arrive seeking the American Dream; they are the result of U.S. American values, part of society, and the future generation of U.S. Americans. They prefer instead to be called “daca mented.”

Dreamers emerged as a strong interest group that found in civil association the only way to achieve their demands; they formed organizations with formal structures that became civil society However, their main weakness is the informality and limits of their social capital (Nicholls, 2013). As Cohen and Arato (1994) explained in their work, civil society is made up of spaces for socialization, forums for dialogue, and channels for dissemination. For Dreamers, in addition, association became a convergent space for an already politicized sector of U.S. American youth.

In general, and for analytical purposes, we identify two different kinds of Dreamers. The first involves young immigrants participating in advocacy associations in localities with dense immigrant populations. In most cases, they only have a high school diploma, but they have real experience working with organizations, community engagement, and social activism. They are leaders of groups committed to immigrant rights defense; these Dreamers previously worked with legal assistance and sponsor organizations. On the other hand, we find Dreamers’ organizations born inside universities and community colleges that had previously accepted the enrollment of undocumented students. This includes the cases of UC Dreamers, Longhorn Dreamers Project (University of Texas, Austin), and Students Working for Equal Rights in Florida. These groups added sophisticated forms to structured organizations and the broad use of social networks. Both kinds of Dreamers came together in the movement and complemented each other with socio-political leadership skills.

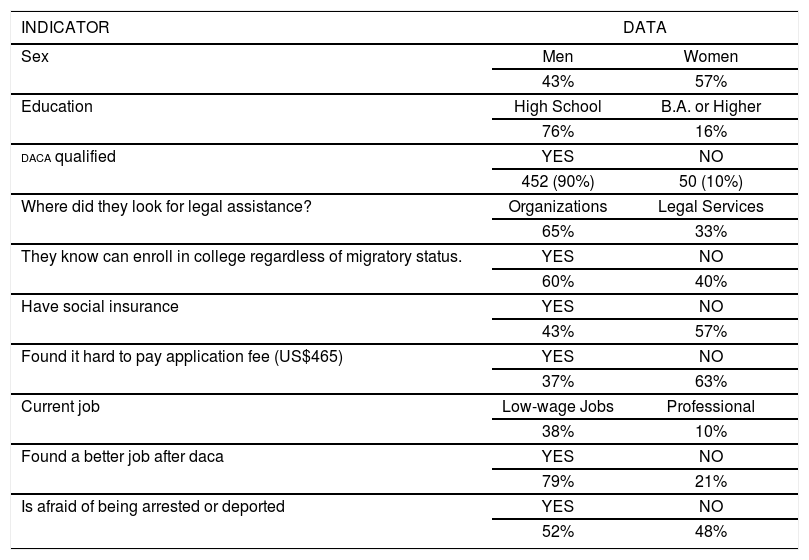

To create a profile of the Dreamers, Patler and Cabrera (2015) designed a study with focus groups in Los Angeles County. They found the following:

| INDICATOR | DATA | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | Women |

| 43% | 57% | |

| Education | High School | B.A. or Higher |

| 76% | 16% | |

| daca qualified | YES | NO |

| 452 (90%) | 50 (10%) | |

| Where did they look for legal assistance? | Organizations | Legal Services |

| 65% | 33% | |

| They know can enroll in college regardless of migratory status. | YES | NO |

| 60% | 40% | |

| Have social insurance | YES | NO |

| 43% | 57% | |

| Found it hard to pay application fee (US$465) | YES | NO |

| 37% | 63% | |

| Current job | Low-wage Jobs | Professional |

| 38% | 10% | |

| Found a better job after daca | YES | NO |

| 79% | 21% | |

| Is afraid of being arrested or deported | YES | NO |

| 52% | 48% | |

Source: Developed by the author using data from Patler and Cabrera (2015). Population: 502

This chart expresses how daca allowed some Dreamers access to education and some economic gains, but the real impact for the beneficiaries, the young generation and the whole country, will be seen in coming years. As Putnam (2001) stated, only education, opportunities, and the right development structures are able to raise social capital, and only high-social-capital civil society is able to promote assertive and durable changes.

Dreamers put forth the phenomena of subsequent generations of immigrants, who have to reconstruct their identities based on differences and renew the identity for the entire peer group (Lesko and Talburt, 2012). According to Louie (2002), the notion of generation is mainly relational since it implies identification with peers, but also differentiation with contemporary, future, and subsequent groups of individuals.

In fact, according to the Migration Policy Institute (2014), Dreamers are 91% Latinos. In general, Latino activism in the United States is characterized by “grassroots political mobilization” (Zlolniski, 2008), which refers to non-electoral activism that occurs when a minority is excluded from the national project designed for the mainstream. These grassroots movements’ main goal is to legitimize the sector’s economic, political, or social capital to influence decision-making schemes, putting forward minority demands and interests. Nevertheless, an essential issue for understanding the Latino experience is that collective action has been marked by the intermittent formation of political organizations. There are less permanent organizations consolidated as formal interest groups rather than associations with short- and medium-term goals. The last case, once a reform has been achieved, tend to disappear due to the lack of long-term consensual agendas, or once their leaders become officials, such as in the cases of Latino federal congresspersons Congress (Perez 2011).

These favorable skills and advantages motivate Latinos, as a consolidated ethnic group, to find in young immigrants the heirs of a strong and historical movement founded on civil association. This relationship increases Dreamers’ social capital, but first they need to face other weaknesses and challenges on the road to becoming the heirs to the Latino leadership and a social force with real weight in political negotiation in the United States. In this case, Dreamers as one-and-a-half and second generation members develop several functions through their activism, advocacy, and association (Seif 2016). They relate to ethnic groups of immigrants who are their first ambit socialization, starting within their families and communities (Mahatmya and Gring-Pemble, 2014). In addition, they negotiate with the mainstream the recognition of the country’s plurality; and also they contest false labels and stereotypes. This social movement marked a key juncture for citizen association, primarily because of the involvement of an entire generation in immigration debates (Mena Robles and Gomberg-Munoz 2016). The Dreamers formed associations capable of intercommunicating with a well-identified immigrant minority group, and they are also developing increasing long-term social capital inside a social core of U.S. society.

MethodologyThe puzzle that guides this article is the following: Why are Dreamers the prospective leaders of the Latino minority in the U.S.? What are their assets and challengese in a country that conceives of politics as negotiation and social change only through organization?

This article’s principal hypothesis is that U.S. political participation is grounded on two foundational pillars: representation by government and organization by society. Following this schema, Dreamers as organized young undocumented immigrants have opportunities and assets for political engagement and prospective immigrant minority leadership. They have developed formal and informal mechanisms of participation based on associative techniques. However, the current strategy, the management of their social capital, and the positioning of long-term goals and future objectives, are, in short, the main challenges.

This article’s methodological strategy consists of a first stage that revisits the theoretical foundations for association as the most propitious way forward for social change in the United States. I analyze the classical approaches that explain how civil association has been an intrinsic characteristic of U.S. politics. Moreover, I particularly focus in contemporary work analyzing group consciousness creation and social capital approaches developed by Putnam (2001), Stokes (2003), and Sanchez (2006) to explain how Dreamers have appropriated citizen association mechanisms to become insiders in the contemporary North American political chest and take shape as a capitalized minority.

Later, I use political opportunity structure to analyze Dreamers’ opportunities, weaknesses, and challenges in assuming the leadership in immigration debates and creating bridges of communication between the U.S. mainstream and immigrants. Scholars such as Siemiatycki (2011), Nicholls (2013), and Triviño (2014) argue that political opportunity models are viable for explaining the environment of immigrants’ political participation, and they have especially focused on representation (agency). Clearly, understanding that the relationship between context and action is critical to tackling the larger theoretical question of the relationship between structure and agency, the political opportunity approach permits the analysis of the institutional gatekeepers who can promote or hinder immigrants from accessing to migration policy-making structures (Triviño 2014).

Political opportunities structures help explain the context in which immigrants have strong associative networks and already shown their organizational capital through active participation. Political opportunity structure promises to predict variance in the periodicity, style, and content of activist efforts and more mainstream institutional responses (Meyer and Minkoff, 2004) and explain how far macro-structural phenomena (the structure) determine agency (Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood, 2016), in this case to explain the kind of leadership. Simultaneously, formalistic, and also substantive representation of minorities depends to some degree on the rules that govern the political system (Bird, 2005). The change of governments is measured in terms of “political openness” and, for immigrants, in gains of “organizational and social capital” (Schrover and Vermeulen, 2005; Sanchez, 2006).

Revisiting the Theoretical Foundations of Civil Association in the U.S.Contemporary governments in general reject the obsolete dogma that nation-states are monolithic entities, cohesive through social homogeneity, whose guidelines exclusively respond to the achievement of “common welfare” perspective promoted from the mainstream. In contrast, the ascent of civil association to the formal and informal political arenas of negotiation, in addition to the adoption –at least in name– of vanguard governance visions that promote the participation of minorities and the rights of difference, have together encouraged a more plural conception of democracy. Precisely, these mechanisms to promote social change have been seized by disadvantaged groups such immigrant associations. Moreover, civil association endorsed processes of globalization from below driven by immigrants (Portes, Guarnizo, and Landot, 2003).

Association and representation principles have been the pillars of U.S. American democracy (Tocqueville, 1985). The U.S. government is based on representation mainly through the legislative branch (Congress); the representatives embody the citizens; and senators represent the states. Furthermore, commoners’ main prerogatives are voting and organizing to achieve their minority interests. In this case, organization and formation of interest groups have been primary mechanisms for promoting social change. With organization, individuals’ particular interests turn into demands; through organization, local demands link up with collective demands. They become strong, acquire voice and capability; organized minorities find fluid channels either within existing institutional opportunities, or even generating social and political arenas that make their social capital visible.

Locke was among the precursors who explained the causes and consequences of civil association. Due to the impossibility of omnipresent governments and the incomplete schemes of governmental representation, citizens naturally would be aware of their opportunities for building agreements and finding their own ways and solutions for their demands; association is then framed as part of the preservation of their lives, liberties and property (Locke, 1969). Nevertheless, it was Ferguson who fully analyzed the emergence of civil society. He explained that historically humanity constitutes groups for self-preservation and happiness; sometimes based on affinity and at others against opinions, rules, and discord. Ferguson stated that “public good” was individuals’ main objective, but “individual good” is the main goal of civil society (Ferguson, 1767).

In modern times, Lipset broadly described how civil society is a fundamental component of democracies, where power is less centralized and a more functional articulation exists between practices and institutions. Taking U.S. politics as his main reference point, he explains in his well-known book Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics how social organization inside institutional channels would pressure policy design (Lipset, 1960). Cohen and Arato (1994), meanwhile, described “civil association” as the space that emerges from social movements, independent of the state, as representative spaces of communication, socialization, organization, and mediation for societies. Citizen associations are then spheres of interaction between economy and polity, which create forms of self-constitution and mobilization in the contemporary world in order to smooth social differences.

Framed under liberal paradigms, classical and contemporary authors help to understand the foundational bases of the political arena and the desirable organized social participation in liberal democracies. Citizens living in liberal democracies discover in civil society the collective potential to influence social, politic, and economic agendas and changes. Due to the diverse intergroup relations converging in collectivities, the scope and attributions of governments are narrow, and some particular issues are neglected or vanish altogether in the face of other priorities. Precisely, minorities have taken most advantage of these circumstances. After identifying their particular ideologies or interests, minorities organize their social capital and through collective action attempt to subjectively influence their socio-political surroundings. Then, civil society relates with the principles of co-responsibility and social inclusion to achieve the co-development of all the agents that make up the socio-political imaginary.

Particularly in the United States, historic experiences such as the pioneers’ tradition of assembly have resulted in the conception of association and organization as the fundamental political guidelines for the state project. Moreover, the founding fathers stated this in the early draft of the national project. Even “the father of the Constitution,” James Madison, pointed out in The Federalist no. 10, that government of the Union should be instituted on existing civil society mainly developed by interest groups (Hamilton, Madison, and Jay, 1776). But, essentially, it was Tocqueville (1985) who fully described the U.S. as a country founded on civil association: Of all the countries in the world, America has taken greatest advantage of association and has applied this powerful means of action to the greatest variety of objectives. Apart from permanent associations created by the law… a multitude of others owe their birth and development only to individual wills.. ..The neighbors soon get together as a deliberative body; out of this improvised assembly will come an executive power that will remedy the difficulty….There is nothing that human will despairs of achieving by the free action of the collective power of individuals.

In sum, these interest groups consolidate processes of civil governance, not only through the constitution of factions looking for recognition of their minority interests; in addition, citizens become proactive, proposing agendas and programs through organizations linked with official channels of participation. Under these circumstances, group adhesion contributes to association (Sanchez, 2006), and association has become the legitimate civil road for political and social participation in the United States. As a result, association is derived from the conception of the relative remoteness of governments due to their national focus and the diversity of their functions. Therefore, civil associations respond to immediate and specific demands that differ from the priorities of the collectivity.

This impetus for organization is based on “group consciousness,” which implies a conscious identification with a cluster against lack of opportunities or discrimination. The basis of ethnic or cluster civil association and later political participation is group consciousness (Stokes, 2003). In fact, a generation is a cluster sharing common social circumstances and a future; consciousness builds consensus about “who they are” and “what they should do to have a more cohesive society, to be better positioned, and to be sure and their countries are better positioned.” Additionally, undocumented youth find in their vulnerabilities a strong motivation to become participatory agents. Using their groups as a starting point, Dreamers develop social and political innovation agendas for the whole immigrant minority, and at the same time they link up with other agents for social change (Masuoka, 2006).

It is noteworthy that this participatory impulse derived from group consciousness is only fruitful when they achieve “social capital.” Putnam is another reference for analyzing civil association in the U.S.; he developed the concept of social capital. He describes civil association as the sum of citizen engagement, solidarity, political equality, tolerance, trust, and participation. Putnam based the formation of social capitalized associations on the networks created by a favorable political context, positive perception of the mass media, knowledge of public affairs and effective channels of organization (Putnam, 2001). Putnam agrees with Tocqueville about the importance of organizations in U.S. but, he considers that in the contemporary U.S., the civil association has lost its sense of community and only the revaluation of social capital is reviving this practice (Putnam, 2001).

Precisely, this is the current arena for social and political participation for undocumented young immigrants aim to incorporate to U.S. society. Highlighting the bridges tended with other forms of Latino collective action, the biggest ethnic minority with the highest growth rates in the United States (Passel and Lopez, 2012). Additionally, as mentioned above, Dreamers are mostly Latinos –they even refer to Latino leaders and their mobilizations as examples–, and Latino movements have paved the way for all immigrant organizations, including Dreamers.

In general, Latino activism in the United States is characterized by “grassroots political mobilization” (Zlolniski, 2008); this refers to non-electoral activism that takes place when a minority is excluded from the national project designed for the mainstream. These grassroots movements’ main goal is to legitimize the sector’s economic, political, or social capital to influence decision-making and to put forward minority demands and interests. Nevertheless, an essential issue for understanding Latino experience is that collective action has been marked by the intermittent formation of political organizations. Less permanent organizations have consolidated as formal interest groups rather than associations with short- and medium-term goals. The latter tend to disappear once a reform is achieved due to the lack of long-term consensual agendas, or once their leaders become officials, such as in the case of Latino legislators in the U.S. Congress (Perez, 2011).

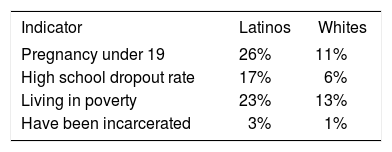

Opportunities and Challenges for Dreamers’ Present Association and Prospective LeadershipIn his work Strangers among Us: How Latino Immigration Is Transforming America,1 Roberto Suro described the panorama for young immigrants, especially young undocumented Latinos living in U.S. cities: Dropout rates are only one symptom. This massive generation of young people is adapting to an America characterized by the interaction of plagues. Their new identities are being shaped by the social epidemics of youth homicides, pregnancy, and drug use, the medical epidemic of aids, and a political epidemic of disinvestment in social services. These young Latinos need knowledge to survive in the workforce, but the only education available to them comes from public school systems that are on the brink of collapse. They are learning to become Americans in urban neighborhoods that most Americans see only in their nightmares (Suro, 1998).

Actually, contemporary statistics reinforce this adverse context for young Americans members of vulnerable minorities:

How Young Latinos Come of Age in America

| Indicator | Latinos | Whites |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy under 19 | 26% | 11% |

| High school dropout rate | 17% | 6% |

| Living in poverty | 23% | 13% |

| Have been incarcerated | 3% | 1% |

Source:Pew Hispanic Center (2013).

Nevertheless, Dreamers are seen by immigrants and mainstream society as survivors of this hostile context; they embody the good moral character of immigrants in the collective imaginary about the American Dream. They represent stories of self-improvement and overcoming adversity. This image contributes to the possibility of their becoming ethnic leaders; they are key agents due to their capacity to meld minorities with the mainstream because they represent the validity of an increasingly eroded American Dream. Young immigrants have built a bridge for inter-ethnic communication: on the one hand, for those in the mainstream, they are involuntary border crossers, and at the same time, for immigrants, they represent the brighter future that sparked border-crossing in the first place. These young immigrants grew up with American values regardless of their legal status; they are desirable immigrants educated above the average, and as Huntington (2004) told the Latino community, Dreamers learned to dream in English.

In addition to variables such as density, self-improvement, and a positive perception by the U.S. mainstream; another considerable advantage of Dreamers for gaining Latino leadership is their political experience, a key feature of social capital in a country that conceives of social changes only through organization and thinks of politics as negotiation. Moreover, as Eisema, Fiorito, and Montero-Sieburth explain, Through their political and civic engagement in the undocumented youth movement, undocumented and educated youth: 1) overcome their fear of migration authorities and feel empowered; 2) enhance their collective status by transforming highly stigmatized youth into successful and legitimate political subjects; 3) acquire a professional activist disposition; and 4) gain access to a large and open network that offers them job, internship, and funding opportunities (2014: 27).

All these features smoothe their incorporation into the society that they already identify as their own. These advantages of civil association also legitimize them as minority leaders able to direct the whole immigrant debate nationwide.

In sum, in today’s scenario, Dreamers bring together many skills and opportunities: 1) In the United States civil association is seen as the main channel for promoting social change; 2) The Dreamers’ network of organizations is framed in the founding political principles of association and representation; and 3) the social capital they have achieved as a group. In contrast, the main challenge for Dreamers has been the strategy oscillating between formal and informal mechanisms of participation.

Several works show how undocumented youth have entered into public offices, set up roadblocks, interrupted official speeches, self-deported and made undocumented re-entry, among other massive forms of protest (Lisa Martinez, 2014; Milkman, 2014; Nicholls and Fiorito, 2015; Zimmerman, 2011, 2012). The most famous has been “Coming Out of the Shadows,” a massive demonstration in Chicago held each year to show the Dreamer’s density and social capital. The main problem is that these mechanisms are not seen as viable for pursuing social claims in U.S. politics; what is more, conservative politicians and media have condemned them as “civil disobedience.” Numerous Dreamers have been arrested after overwhelming protests in Washington, Los Angeles, Miami, El Paso, actions widely covered by national press (Preston, 2010; Fox News Latino, 2013; Washington Post, 2013).

These events are perceived as inappropriate in a country that in general conceives of socio-political change only through institutional channels. Zimmerman explains: The civil disobedience reflects how the undocumented youth movement has transitioned and transformed —from a movement that was initially focused on building support for the dream Act to one that has increasingly used direct action to bring attention to broader issues of immigrant, civil, and human rights as a strategy for social and policy change. The tactical shift has been in response to a changing political context in which the will to pass immigration reform has waned in Washington, deportations are on the rise… and law enforcement is transferred to the local and state level within the context of neoliberal restructuring. The civil disobedience reflects how the undocumented youth movement has transitioned and transformed—from a movement that was initially focused on building support for the DREAM Act to one that has increasingly used direct action to bring attention to broader issues of immigrant, civil, and human rights as a strategy for social and policy change. The tactical shift has been in response to a changing political context in which the will to pass immigration reform has waned in Washington, deportations are on the rise… law and enforcement is transferred to the local and state level within the context of neoliberal restructuring (2012: 14).

In general, the long road to regularization and gaining civil and political rights is taking time; meanwhile, Dreamers have taken action, organizing and associating inside and outside the established institutions, becoming active agents in the process of constructing a more equitable context for the minority and a pluralist future for the generation as a whole (Weber-Shirk, 2015).

Recently, these strategies have become more sophisticated. Dreamers are now received by U.S. officials and representatives; they have properly articulated political discourses that go beyond narratives and have linked with hometown consulates and transnational programs. To mention a few examples, President Obama invited Dreamers as honored guests (White House, 2016) to the 2012 and 2016 State of the Union addresses. On the other side of the border, Mexico’s Minister of Foreign Relations invited 40 young immigrant organization leaders to visit the country in 2014; this invitation was repeated in 2015, on that occasion for the “Youth and Migration” forum, where authorities, academics, and young immigrants gathered to exchange experiences and workshops to design programs (sre, 2015).

In contrast, relations with the U.S. government have fluctuated between agreements and confrontation (Rafael Martinez, 2014). At the 2014 State of the Union address, Dreamer Blanca Hernandez interrupted President Obama, confronting him about his passive stance on immigration reform and the risk of the cancelation of daca. This action was replicated several times in the offices of Marco Rubio, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump, among other politicians and legislators.

Some remarkable groups support the whole network created by the Dreamers; these national-scale organizations are good examples of vanguard civil association. The first case is the National Immigrant Youth Alliance (niya), whose slogan is “To empower, educate and escalate.” Diana Bryson states, niya is known for its dissident tactics, drawing criticism from other human rights groups, immigration advocates, and even former allies in Congress. Rep. Luis Gutiérrez (D-IL) released a statement in November officially breaking ties with the group and with dream-activist.org, affiliated with niya (Bryson, 2014).

This organization’s main actions have been massive attempts of returnees to cross the border, the occupation of ice offices, and confrontation of legislators (Pallares, 2014).

A contrasting example is United We Dream. In their own words, United We Dream is the largest immigrant youth-led organization in the nation. Our powerful nonpartisan network is made up of over 100,000 immigrant youth and allies and 55 affiliate organizations in 26 states. We organize and advocate for the dignity and fair treatment of immigrant youth and families, regardless of immigration status (United We Dream, n.d.).

In 2008, the National Immigration Law Center hosted a conference in Washington, D.C., attended by members of the associations; the youth held a workshop and the result was a coalition. They outlined action fields and created a program for each of the following: daca, Education No Deportation (end), Queer Undocumented Immigrant Project (quip), Dreamers Education Empowerment Program (deep). They have a Board of Leaders for decision-making, a National Council that determines agenda, and a professional staff for management, communication, operations, advocacy, and policy. All these characteristics reflect the sophistication of social capital that Dreamers associations aim to achieve.

Although by 2015 a Texas federal court blocked the expansion of daca, it is notable how the outstanding association dynamism grounded in group consciousness and the growth of national-scale organizations based on civil association maintain their presence in the public sphere. Dreamers have already demonstrated their social capital and in some states have earned legitimacy and shifted local migration policy beyond failed legislative debates and the lack of a federal response. Weber-Shirk explains: Actions like these are ‘immigration reform in practice, taking action to reunite families even as it means defying nation-state borders, asserting communities of belonging even while declaring non-citizen status, and influencing the conversation about citizenship in the process (2015: 583).

Under these circumstances, the main concern for collectives of Dreamers should be replacing “resistance” with “resilience,” which means intelligently linking up group consciousness and social capital with smart socio-political strategies.

In this sense, one of their priorities should be the consolidation of proactive leadership in accordance with the real needs and potential of the human capital of all the Latinos in the United States, moving beyond demands merely for regularizing migratory status to the outline of an entire ethnic agenda. They should focus on the decisive transition from being life-storytellers to becoming assertive political actors (Cigarroa, 2013). This shift means basically to project medium and long-term mechanisms to transition from informal civil association networks to a political force that leads minority demands (Wang et al., 2014). They have this opportunity inside a group that conceives of them as the living example of the viability of the American Dream.

These Dreamers with political skills and associative experience are the future leaders of Latino politics, ground previously paved by Latino organizations, the Hispanic Caucus and other consolidated U.S. policy networks that have earned sympathetic support due to the smart use of U.S. American institutional channels for promoting social change and immigrant empowerment (Barero, 2014).

The importance of collective action lead by the undocumented, in all the liberal democracies, is not measured by the same parameters as other social movements. In fact, the collectives of the undocumented struggle to stop being, bad start for the consolidation of an organized social movement (Suárez-Navas et al., 2007).

It is important to point out that “dreamers now talk about the ‘intersectional’ character of their struggle. They are not only undocumented Americans; they are also Queer, minorities, women, and so on” (Nicholls and Fiorito, 2015). Furthermore, in the most optimistic scenario for the future, this “intersectionality” of the movement gives this youth the future opportunity to become social and political leaders of the whole, increasingly plural U.S. society

DiscussionThe Dreamer’s movement is more properly understood analyzing the group’s social and political assets (group consciousness and social capital), but also the complex chessboard for participation in the U.S., based on the foundational pillars of representation and association for political engagement.

The United States is a country that from its founding outlined mechanisms for civil organization in order to protect minorities against the “tyranny of the majority,” but only when these associations are capable of self-structuring as interest groups (Hamilton, Madison, and Jay, 1776). Under these circumstances, political change in the U.S. is possible, but only gradually, from grassroots to institutions, and always moving amidst institutional channels. This means that the lack of smart political strategies and a deficient connection with consolidated organizations would only lead to recognition, demands, and pressure, but not to long-term policies and programs to improve the future of young immigrants.

With regard to the social context, this article explained that group consciousness is the mainspring for civic association. Previous literature on group consciousness (Stokes, 2003; Sanchez, 2006) has indicated its multidimensional character, with three distinctive components:

- 1.

Group identity: I have argued how previous Latino mobilizations are the precedents and roots of contemporary young immigrants’ association, with the difference that Dreamers are generational and cross-cutting.

- 2.

Recognition of disadvantaged status: I have explained that the smart use of social media became the space for socialization and strengthening the network (McDevitt and Sindorf, 2014). Through videos and blogs, Dreamers told their life stories, how they were discriminated against for being undocumented, talked about the deportations of their family members, how they were admitted to universities that allowed undocumented students to enroll, and the lack of tuition monies and grants for not being citizens.

- 3.

Desire for collective action to overcome that status: after Dreamers realized there were 11 million undocumented immigrants, even before official statistics did, they achieved group consciousness, declared themselves “Undocumented, unafraid and unapologetic” and associated with each other.

The final approach for explaining Dreamers as a civic association movement capable of become the leaders of Latino minority was social capital. The axes of social capital are, in summary, civic engagement, solidarity, political equality, tolerance, trust, and participation (Putnam, 2001). Precisely, Dreamers’ social capital increased with the maturation of their association; they created sophisticated solidarity and trust networks. Their previous involvement in immigrant rights advocacy associations or student organizations gave their members strong civic engagement and valuable organizational experience. In the same direction, Putnam (2001) states the need for a favorable context, which includes an encouraging network of an auspicious political context, a positive perception by the mass media, knowledge of public affairs, and effective channels of organization.

In this sense, is the current scenario a favorable political network? The answer is not clear; politicians from different branches of government, opposite political affiliation and from cities and the countryside have recognized the problematic broken migration system and urged a migratory reform. The main problem is that nobody agrees on the direction and the content of such a reform. With regard to the perception by the mass media, bias is a reality, and the reports and news about young immigrants’ campaigns conform to the posture adopted by their audience. The Dreamers’ main advantage is that they are remaining in the limelight and their actions are noticed nationwide.

About the knowledge of public affairs, Dreamers politicized an entire generation in the U.S. They learned about low politics; they found out about their rights; they partnered with other civil society organizations (labor unions, professors, ethnic groups, etc.); they linked up with legal services to help the community safely apply for daca. With regard to high politics, they transitioned from only “civil disobedience” to the mixed strategy of radical actions plus smart politics. Dreamers abandoned confrontation discourses for sensitive and valorization discourses; they became expert political speakers in distinguished forums such the U.S. capitol. Finally, about effective channels of organization, Dreamers have sophisticated organizations: in most cases, they have a executive board, plenaries for decision-making, and administrative branches for each of their programs. Organizations such United We Dream and the National Youth Immigrant Alliance have even a yearly national congress for local leaders.

Although Dreamers have developed many skills and have many political opportunities as prospective Latino leaders, what are the current and prospective challenges? The main challenge is balancing pressure tactics (especially “civil disobedience”) and smart political strategy. A second key issue broadly explained in this article was the need for medium and long-term goals: immigration reform is obvious; the meaning of such laws and policies are not. Dreamers need to draw prospective scenarios and durable strategies. Third, Dreamers need to maintain and manage the unifying nature of their movement that enables them to mediate between the mainstream and immigrants for the advancement of intercultural relations. And finally, they must link up and forge a win-win relationship with national, consolidated organizations like La Raza and officials inside the Hispanic Caucus, with all these associations’ access to high-level politics.

ConclusionDespite their multiple vulnerabilities (being young, from an ethnic minority and undocumented), Dreamers are currently an important movement in contemporary U.S. politics. They politicized a considerable sector of U.S. youth and divided positions inside the mainstream. Furthermore, they motivate identity debates within a society that increasingly asks, “Who are we?” They also challenge the U.S. mainstream to go further, demanding to know when they will be considered to be “home.” What are the real criteria for belonging? When will you notice that despite our complex identities, we are already a considerable part of the new generation of U.S. Americans?

The Dreamers’ future is not yet written; their migratory regularization process is still uncertain because daca and dapa are far from being permanent solutions. However, they have already opened the field for further research for several topics and disciplines. This article aims to explain Dreamers beyond riots, very specific or limited organizations, and life-story narratives. It uses approaches from political sociology, with frameworks such classical and contemporary theories about association in U.S. politics, and later applies social capital and political opportunity perspectives.

I explained how the Dreamers built an organized cluster through their strong networks with efficient communication strategies and channels for dissemination; how they developed an assertive association with intergroup articulation (across the local and different groups of Dreamers) and intra-group relations (with advocacy and pro-immigrant organizations); and also how they mobilize using informal mechanisms, but especially through formal mechanisms of participation in U.S. politics.

Nevertheless, I found several assets and opportunities to put Dreamers in perspective. Highlighting how they are able to build bridges of communication between immigrant or ethnic minorities and the U.S. mainstream, I also emphasized the key role of their developing political experience and the importance of their originality, identity, and consciousness that enables cohesion, permanence, and consolidation as a minority.

In contrast, many remarkable challenges exist. I explained the lack of long-term goals and future objectives beyond migratory status regularization. I described that the way to become effective political agents is still uncertain, as well, how to channel participation, increase their social capital, and empower their members within an increasingly polarized society. I argued that Dreamers can be the prospective leaders of the immigrant minority —predominantly Latinos—, only if they take advantage of a political scenario where social and political changes are slow but possible, only when the agents understand the rules, if they achieve enough social capital, and when they participate through formal established mechanisms in U.S. politics.

The Knopf edition of this book is catalogued by the Library of Congress as Strangers among Us: How Latino Immigration Is Transforming America, which is how it is listed in the bibliography of this article. [Editor’s Note.]