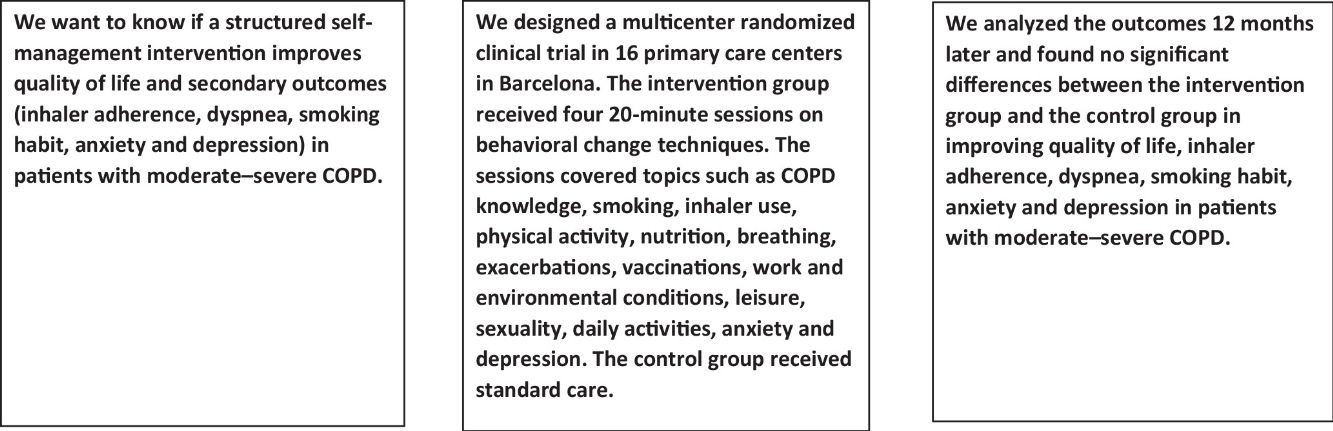

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of a structured self-management program in patients with moderate–severe COPD followed up for 12 months, in improving quality of life, dyspnea, inhaler adherence, anxiety, and depression, compared to standard practice.

Material and methodsThis was a multicenter randomized clinical trial involving 115 patients, 59 in the intervention group and 56 in the control group. Participants from 16 primary care centers in Barcelona, Spain, were allocated consecutively and in a blinded manner to the intervention and control groups in stages. Professionals received training in behavioral change techniques. The intervention consisted of four 20-min sessions conducted at 14-day intervals, covering topics such as COPD knowledge, smoking, inhaler use, physical activity, nutrition, breathing, exacerbations, vaccinations, work and environmental conditions, leisure, sexuality, daily activities, anxiety, and depression.

ResultsA total of 102 patients completed the study, 50 in the intervention group and 52 in the control group. Differences between the intervention and control groups in quality of life, dyspnea, inhaler adherence, smoking, anxiety, and depression were not significant.

ConclusionIn patients with moderate–severe COPD, a structured self-management intervention in primary care is not more effective than standard care in improving quality of life, dyspnea, inhaler adherence, anxiety, and depression.

El presente estudio se realizó con el objetivo de comparar la efectividad de un programa estructurado de autocuidado en pacientes con EPOC moderado-grave con seguimiento a los 12 meses centrado en la mejora de la calidad de vida, disnea, adherencia a los inhaladores, ansiedad y depresión con respecto a la práctica habitual.

Material y métodosEnsayo clínico aleatorio multicéntrico. Participaron 115 pacientes, 59 en el grupo intervención y 56 en el grupo control a los que se les hizo seguimiento a los 12 meses. La muestra fue obtenida de 16 Centros de Atención Primaria en Barcelona, España, en la que se realizó la asignación de los centros al grupo intervención y al grupo control, por etapas, consecutivamente y de forma ciega. Se realizó una formación a los profesionales asociados al estudio en técnicas de entrevista motivacional, motivación para el cambio y retroalimentación positiva. La intervención a los pacientes consistió en 4 sesiones de 20 minutos separadas 14 días, sobre conocimientos de EPOC, tabaquismo, uso de inhaladores, actividad física, nutrición, respiración, exacerbaciones, vacunaciones, entorno laboral y ambiental, ocio, sexualidad, actividades cotidianas, ansiedad y depresión.

ResultadosFinalizaron el estudio 102 pacientes, 50 en el grupo intervención y 52 en el grupo control. Las diferencias entre el grupo intervención y el grupo control en la calidad de vida, disnea, adherencia a los inhaladores, tabaquismo, ansiedad y depresión fueron no significativas.

ConclusiónEn pacientes con EPOC moderado-grave, una intervención estructurada en autocuidado en atención primaria con seguimiento a los 12 meses no es más efectiva que la intervención habitual en la mejora de la calidad de vida, disnea, adherencia a los inhaladores, ansiedad y depresión.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by progressive and largely irreversible airflow limitation, and is primarily associated with tobacco smoke. It is a preventable and treatable disease that can present extrapulmonary or systemic effects and is frequently accompanied by comorbidities.1–6 COPD ranks as the fourth leading cause of global mortality.7,8 One of the primary objectives of COPD treatment is to preserve and enhance patients’ health status by alleviating symptoms, improving functional capacity, and increasing quality of life.9

Self-management refers to educational programs designed to equip patients with the skills necessary to manage the specific treatment of their disease, guide changes toward healthier habits, and provide emotional support to enable a functional life.10,11 Wagg12 defined a self-management intervention as one that addresses at least 2 out of 7 skills: self-efficacy, problem-solving, resource utilization, collaboration, emotional management, patient role management, and goal-setting. Systematic reviews of self-management interventions show variability in the methods employed.13–17 These reviews highlight the need to evaluate such interventions through randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up.14,15 Additionally, greater transparency is required regarding the details of these interventions, especially those that include action plans for exacerbations and managing comorbidities.16 Furthermore, the involvement of primary care specialists improves the quality of life for COPD patients.16 It is essential for professionals to master behavior change techniques (BCTs) to motivate patients and enhance their disease management.17

This study was conducted to compare the efficacy of a structured self-management program in patients with moderate to severe COPD with a 12-month follow-up, focusing on improvements in quality of life, dyspnea, inhaler adherence, anxiety, and depression, compared to standard care.

Materials and methodsThis study is a multicenter, randomized controlled trial with a 12-month follow-up and a control group. It was conducted across 16 primary care centers (CAP – centros de atención primaria in Spanish) in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, part of the “Àrea Integral de Salut Nord” (AIS Nord, 310,852 patients), using the e-CAP electronic medical records system. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (CEI) of the Jordi Gol Primary Care Research Institute (IDIAP Jordi Gol), code P17/055.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03762330.

Once the participating investigators were recruited, a stratified randomization of the CAPs was performed in 4 stages. In each stage, the CAPs were grouped according to the number of participating investigators and then randomly assigned to either the control group or the intervention group consecutively. The researcher conducting the randomization was blinded to the group assignment of each CAP.

Patients were considered eligible for the study if they met the following criteria:

- a)

Had visited the CAP at least once in the past year.

- b)

Had a diagnosis of moderate COPD (FEV1 50–80%) or severe COPD (FEV1 30–49%).

- c)

Were undergoing treatment with inhalers.

- d)

Were able to attend the primary care center (due to the inability to perform spirometry at home).

- e)

Had no diagnosis of asthma, tuberculosis, or other chronic respiratory diseases.

- f)

Were not receiving home oxygen therapy.

- g)

Had no uncontrolled cognitive or behavioral disorders preventing participation.

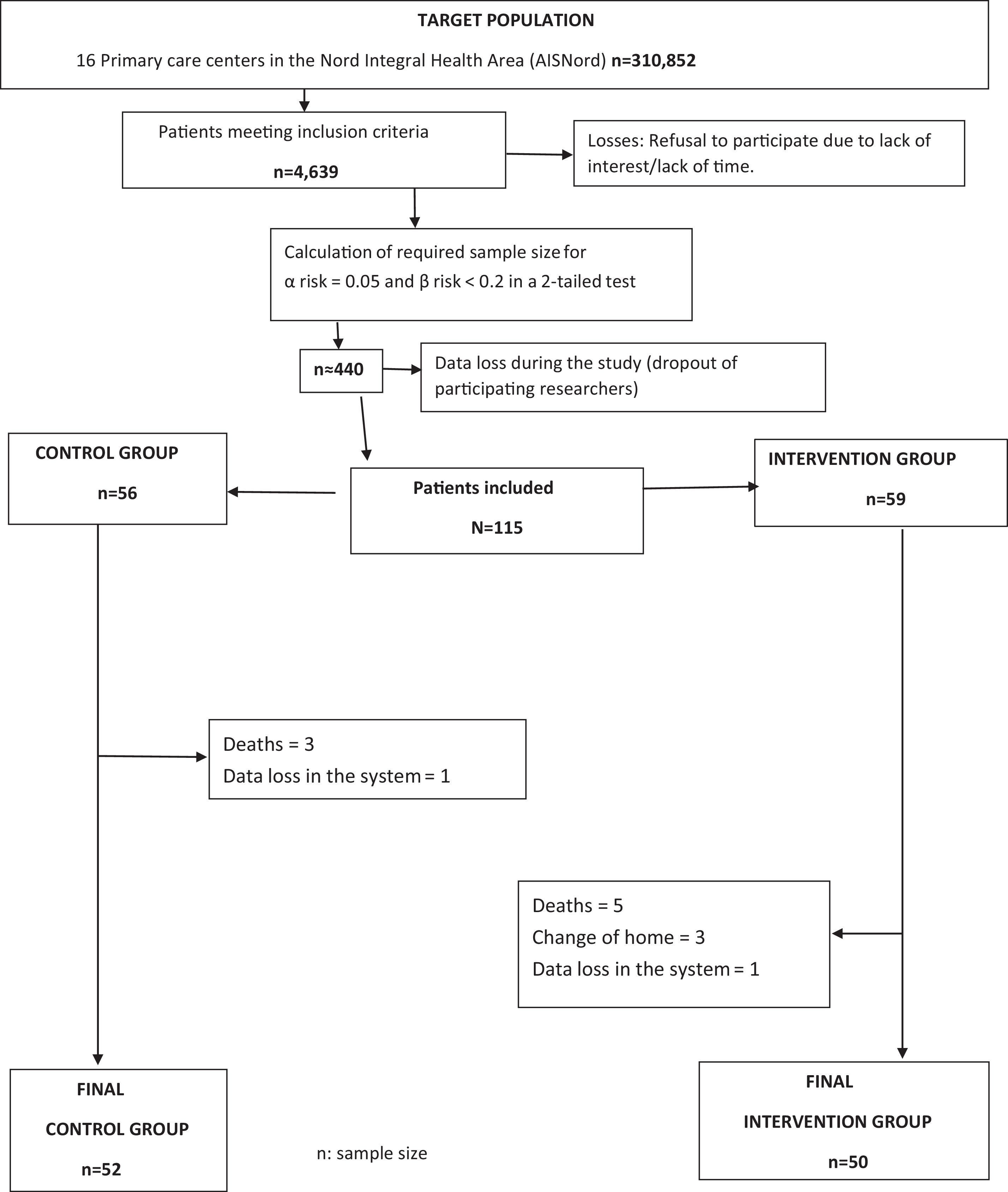

Sample size calculations determined that 150 subjects in the control group and 150 in the intervention group were required to detect a difference of ≥4 units in the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score, assuming a common standard deviation of 11.33, an alpha risk of 0.05, a beta risk<0.2, and a 2-sided test. An anticipated 10% dropout rate was included in the calculations.

Eligible patients were contacted opportunistically by participating researchers by phone, SMS, Internet, or during consultations and invited to participate in the study. If the patient agreed, a visit was scheduled to explain the study in detail, obtain informed consent, and collect baseline data (Fig. 1). All the patients that participate in the study signed the Informed Consent.

Healthcare professionals in the intervention group underwent a specific training course as part of the “Programa d’Atenció Primària Sense Fum” (PAPSF), which included a dedicated module on COPD.

The intervention was structured into four components:

- 1.

Knowledge acquisition and reinforcement regarding key content to convey to COPD patients.

- 2.

Criteria and skill development for personalized intervention.

- 3.

Behavior change techniques (BCTs) and motivational interviewing for health education.

- 4.

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) training.

The four components were delivered simultaneously using simulated clinical consultations with sequential visits to a COPD patient. Each visit, presented via videos, required professionals to make decisions based on their own judgment. Feedback was provided on their choices using a trial-and-error learning approach grounded in real clinical scenarios, with no penalties for errors. Theoretical content was tailored to the professionals’ responses to enhance knowledge. Participants could revisit sessions and progress at their own pace. A knowledge assessment was conducted at the end, using continuous self-assessment and situation repetition, followed by a final hetero-evaluation test to confirm knowledge acquisition.

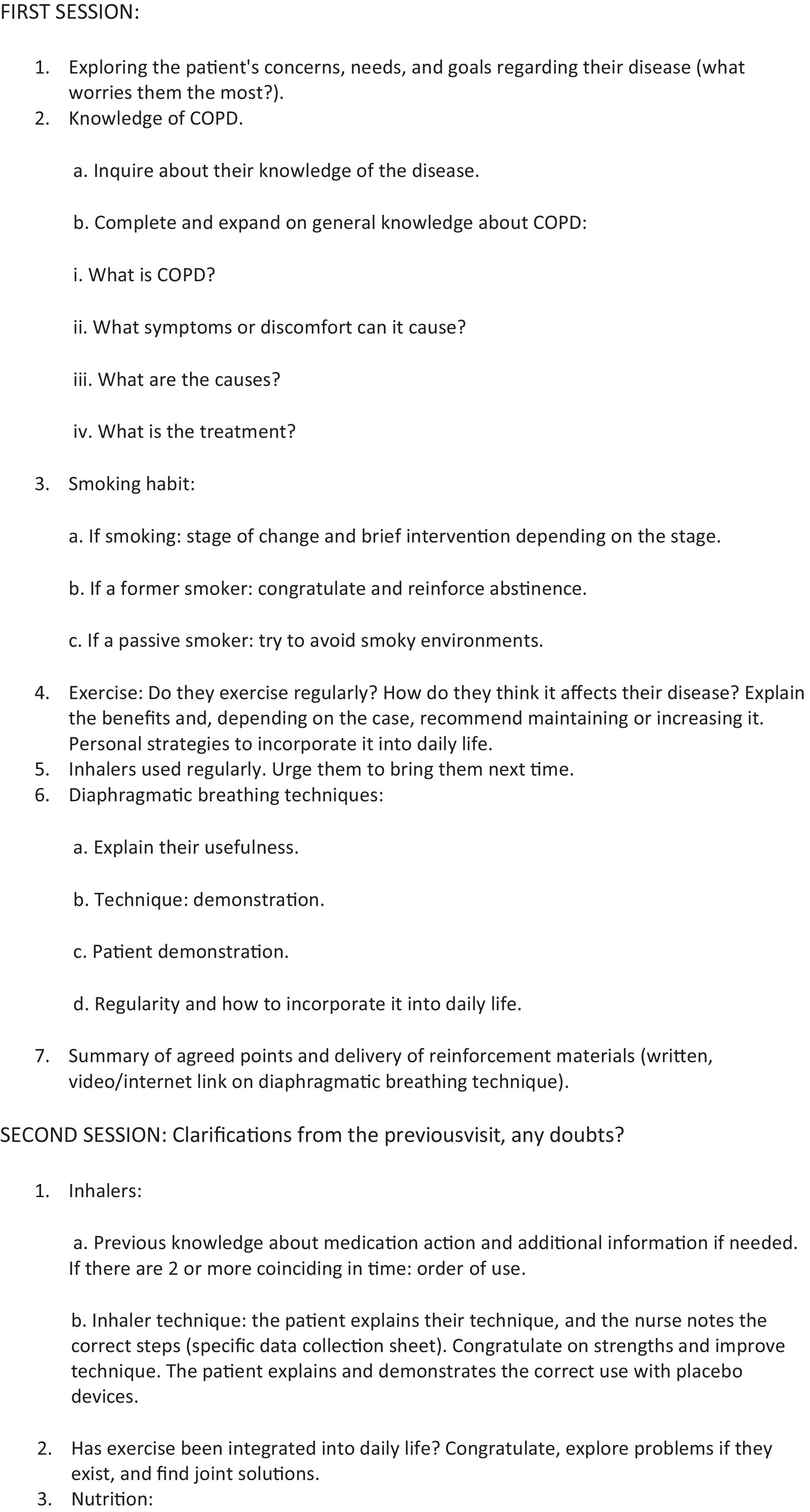

The intervention consisted of four 20-min sessions conducted 14 days apart, with two additional 20-min booster sessions at 12 months. The course materials were used as content for the intervention (Fig. 2).

The control group received standard care according to the COPD Clinical Practice Guidelines, which included general follow-up recommendations without a personalized approach.

Caregivers, if any, were encouraged to participate.

During each session, investigators recorded variables such as quality of life, lung function, dyspnea, prognosis, and hospitalizations using the e-CAP software. Data collected for each patient included age (date of birth), sex, inhalation technique (adherence), depression, anxiety, and smoking status (smoker or ex-smoker, pack-years; for smokers: cigarettes/day, nicotine dependence, motivation for change, and stage of change).

Outcome measures:

- •

Quality of life: assessed with the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ),18 which evaluates general health impact, daily life, and perceived well-being in COPD patients. It consists of 50 items divided into 2 parts, covering 3 components: symptoms, activity limitations due to dyspnea, and social impact (social functioning and psychological issues related to respiratory disease). Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater functional limitation.

- •

Lung function: measured by spirometry, including post-bronchodilator FEV1 and FVC changes.

- •

Dyspnea: evaluated using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale,19 ranging from 0 to 4 (minimal to maximal).

- •

Prognosis: assessed with the BODEx index20 (Body Mass Index, Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exacerbations), with possible scores from 0 to 9 (mild: 0–2, moderate: 3–4, severe: ≥5).

- •

Anxiety and depression: measured with the Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale (GADS),21 a self-administered questionnaire comprising 18 items (9 for anxiety, 9 for depression). Scores ≥4 on the anxiety subscale and ≥2 on the depression subscale indicate significant symptoms.

- •

Adherence: measured using the Test of Adherence to Inhalers (TAI),22 which includes 10 self-administered questions (scored from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating worse adherence and 5 indicating better adherence) and 2 additional questions completed by the healthcare professional (scored from 1 to 2, with 1 indicating worse adherence and 2 indicating better adherence).

- •

Stage of change: measured according to Prochaska and Di Clemente's model.23

A total of 115 patients were recruited: 56 in the control group and 59 in the intervention group. During follow-up, losses and reasons were recorded to identify potential biases. Ultimately, 52 control group patients and 50 intervention group patients completed the study. Data collection occurred between January 2019 and June 2020.

No artificial intelligence tools were was used in the production of the manuscript.

ResultsAnalyses were conducted per protocol and using the intention-to-treat approach. All subjects who signed the informed consent and completed the initial evaluation were included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated for dependent, confounding, and general variables for both the intervention and control groups. Homogeneity of the groups was verified for these variables at baseline. A 2-sided alpha error of 0.05 was considered for all analyses, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

The primary outcome variable was quality of life. Secondary variables analyzed included dyspnea, inhalation technique, BODEx index, smoking status, and anxiety/depression. Outcome measures were calculated as the difference between baseline values for each individual and values at 12 months post-intervention, both for the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and for other dependent variables of interest. Differences between groups were assessed using Student's t-test, with 95% CIs computed for the differences. Results were adjusted by stratifying for the confounding variable COVID-19.

No adjustment to the level of statistical significance was made for analyses involving the 6 different dependent variables. Readers may interpret the observed differences without such adjustments.

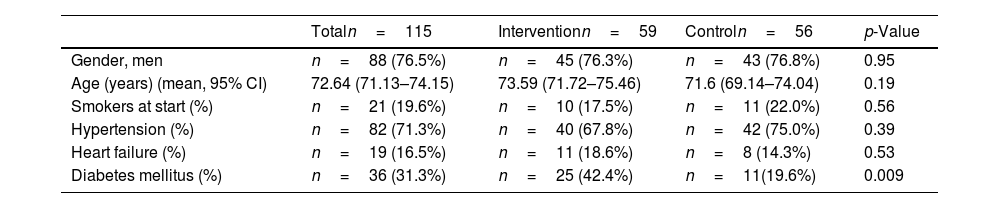

There were significant differences in the variable type 2 diabetes mellitus, which did not affect the comparability of the groups (Table 1).

Comparability of intervention and control groups for variables sex, age, smokers, hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes mellitus.

| Totaln=115 | Interventionn=59 | Controln=56 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, men | n=88 (76.5%) | n=45 (76.3%) | n=43 (76.8%) | 0.95 |

| Age (years) (mean, 95% CI) | 72.64 (71.13–74.15) | 73.59 (71.72–75.46) | 71.6 (69.14–74.04) | 0.19 |

| Smokers at start (%) | n=21 (19.6%) | n=10 (17.5%) | n=11 (22.0%) | 0.56 |

| Hypertension (%) | n=82 (71.3%) | n=40 (67.8%) | n=42 (75.0%) | 0.39 |

| Heart failure (%) | n=19 (16.5%) | n=11 (18.6%) | n=8 (14.3%) | 0.53 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | n=36 (31.3%) | n=25 (42.4%) | n=11(19.6%) | 0.009 |

CI: confidence interval.

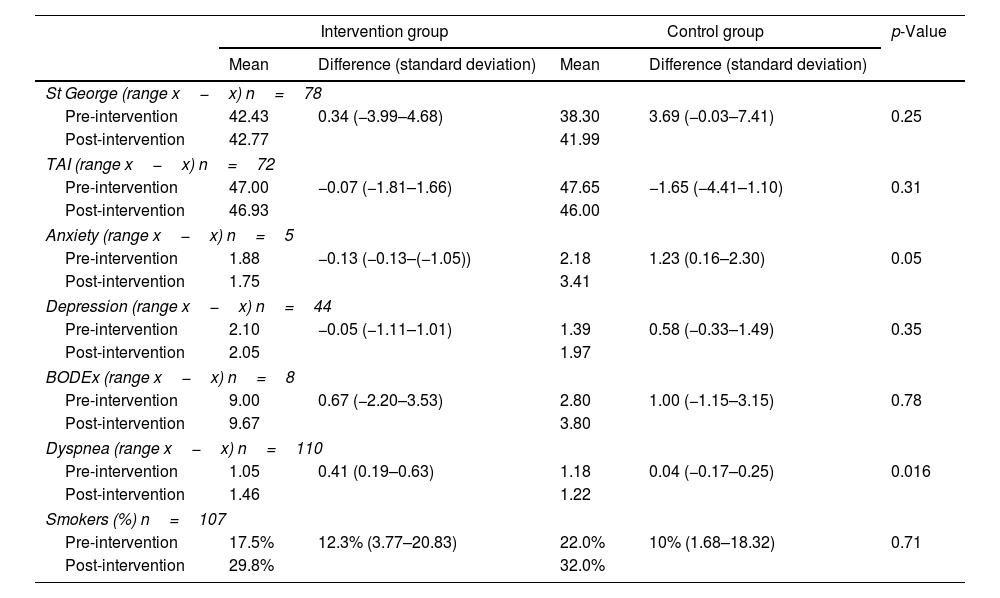

In unadjusted per-protocol analyses (Table 2), the intervention group (IG) showed less deterioration compared to the control group (CG) in SGRQ (quality of life) (p=0.25), TAI (p=0.31), and BODEx (p=0.78), though these were not statistically significant. Anxiety improved significantly in the IG compared to the CG (p=0.05). Depression improved in the IG versus the CG, but not significantly (p=0.35). Regarding smoking status, a non-significant increase was observed in the IG compared to the CG (p=0.71). Dyspnea worsened significantly less in the CG (p=0.016).

Per-protocol analysis of intervention group and control group before and after the intervention.

| Intervention group | Control group | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Difference (standard deviation) | Mean | Difference (standard deviation) | ||

| St George (range x−x) n=78 | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 42.43 | 0.34 (−3.99–4.68) | 38.30 | 3.69 (−0.03–7.41) | 0.25 |

| Post-intervention | 42.77 | 41.99 | |||

| TAI (range x−x) n=72 | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 47.00 | −0.07 (−1.81–1.66) | 47.65 | −1.65 (−4.41–1.10) | 0.31 |

| Post-intervention | 46.93 | 46.00 | |||

| Anxiety (range x−x) n=5 | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 1.88 | −0.13 (−0.13–(−1.05)) | 2.18 | 1.23 (0.16–2.30) | 0.05 |

| Post-intervention | 1.75 | 3.41 | |||

| Depression (range x−x) n=44 | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 2.10 | −0.05 (−1.11–1.01) | 1.39 | 0.58 (−0.33–1.49) | 0.35 |

| Post-intervention | 2.05 | 1.97 | |||

| BODEx (range x−x) n=8 | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 9.00 | 0.67 (−2.20–3.53) | 2.80 | 1.00 (−1.15–3.15) | 0.78 |

| Post-intervention | 9.67 | 3.80 | |||

| Dyspnea (range x−x) n=110 | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 1.05 | 0.41 (0.19–0.63) | 1.18 | 0.04 (−0.17–0.25) | 0.016 |

| Post-intervention | 1.46 | 1.22 | |||

| Smokers (%) n=107 | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 17.5% | 12.3% (3.77–20.83) | 22.0% | 10% (1.68–18.32) | 0.71 |

| Post-intervention | 29.8% | 32.0% | |||

TAI: inhaler adherence test. BODEx: body mass index, obstruction, dyspnea, exacerbations. Post–Pre: post-intervention, pre-intervention. Difference: difference post-intervention-pre-intervention.

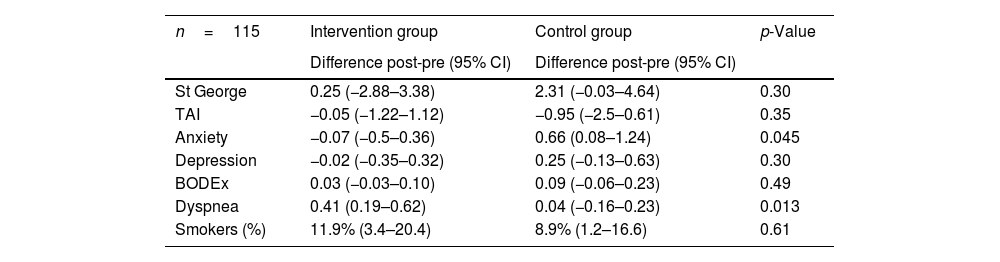

The unadjusted intention-to-treat analyses (Table 3) yielded similar results to those from the per-protocol analysis (Table 2).

Intention-to-treat analysis of the intervention group and the control group before and after the intervention.

| n=115 | Intervention group | Control group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference post-pre (95% CI) | Difference post-pre (95% CI) | ||

| St George | 0.25 (−2.88–3.38) | 2.31 (−0.03–4.64) | 0.30 |

| TAI | −0.05 (−1.22–1.12) | −0.95 (−2.5–0.61) | 0.35 |

| Anxiety | −0.07 (−0.5–0.36) | 0.66 (0.08–1.24) | 0.045 |

| Depression | −0.02 (−0.35–0.32) | 0.25 (−0.13–0.63) | 0.30 |

| BODEx | 0.03 (−0.03–0.10) | 0.09 (−0.06–0.23) | 0.49 |

| Dyspnea | 0.41 (0.19–0.62) | 0.04 (−0.16–0.23) | 0.013 |

| Smokers (%) | 11.9% (3.4–20.4) | 8.9% (1.2–16.6) | 0.61 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval. BODEx: body mass index, obstruction, dyspnea, exacerbations. Post-pre: post-intervention, pre-intervention. TAI: test of adherence to inhalers.

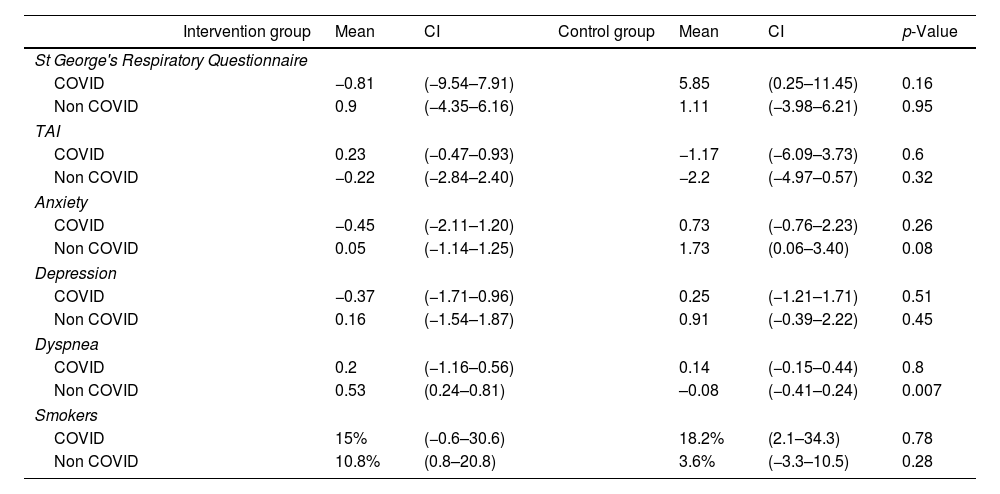

COVID-adjusted results (Table 4): COVID-adjusted analyses showed slight variations in outcomes:

- •

For SGRQ, there was a non-significant improvement in the COVID intervention group (CIG) compared to the COVID control group (CCG) (p=0.16), which was more pronounced than in the “non-COVID” groups (p=0.95).

- •

Improvements in anxiety for both the COVID and non-COVID intervention and control groups became non-significant (p=0.26 and p=0.08, respectively).

- •

Dyspnea continued to improve in the control groups (COVID and non-COVID) compared to the intervention groups (COVID and non-COVID), but this was no longer significant in the COVID control group (CCG) (p=0.8). In the non-COVID intervention group (NCIG), dyspnea improved significantly compared to the non-COVID control group (NCCG) (p=0.007).

- •

Smoking status improved non-significantly in the CIG (p=0.78) but worsened (non-significantly) in the NCIG (p=0.28).

Intervention and control groups adjusted for Covid.

| Intervention group | Mean | CI | Control group | Mean | CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St George's Respiratory Questionnaire | |||||||

| COVID | −0.81 | (−9.54–7.91) | 5.85 | (0.25–11.45) | 0.16 | ||

| Non COVID | 0.9 | (−4.35–6.16) | 1.11 | (−3.98–6.21) | 0.95 | ||

| TAI | |||||||

| COVID | 0.23 | (−0.47–0.93) | −1.17 | (−6.09–3.73) | 0.6 | ||

| Non COVID | −0.22 | (−2.84–2.40) | −2.2 | (−4.97–0.57) | 0.32 | ||

| Anxiety | |||||||

| COVID | −0.45 | (−2.11–1.20) | 0.73 | (−0.76–2.23) | 0.26 | ||

| Non COVID | 0.05 | (−1.14–1.25) | 1.73 | (0.06–3.40) | 0.08 | ||

| Depression | |||||||

| COVID | −0.37 | (−1.71–0.96) | 0.25 | (−1.21–1.71) | 0.51 | ||

| Non COVID | 0.16 | (−1.54–1.87) | 0.91 | (−0.39–2.22) | 0.45 | ||

| Dyspnea | |||||||

| COVID | 0.2 | (−1.16–0.56) | 0.14 | (−0.15–0.44) | 0.8 | ||

| Non COVID | 0.53 | (0.24–0.81) | –0.08 | (−0.41–0.24) | 0.007 | ||

| Smokers | |||||||

| COVID | 15% | (−0.6–30.6) | 18.2% | (2.1–34.3) | 0.78 | ||

| Non COVID | 10.8% | (0.8–20.8) | 3.6% | (−3.3–10.5) | 0.28 | ||

CI: confidence interval; TAI: test of adherence to inhalers.

The results for depression and TAI were similar to those obtained in the unadjusted analyses. The BODEx index could not be analyzed statistically in the COVID-adjusted analysis because some values were ≤1.

DiscussionThe results demonstrate an improvement in quality of life, as measured by the SGRQ, adjusted for COVID-19, although this was not statistically significant. Regarding smoking status, the intervention group showed a decline; however, after adjusting for COVID-19, the decline was observed in the “non-COVID” group and remained non-significant. A study by A. Fiske et al.24 suggests that patients infected with COVID-19 show greater concern for their health and adopt healthier behaviors. The lack of significant improvement in dyspnea in the “COVID” control group could be attributed to pulmonary compromise from the infection. Conversely, in the “non-COVID” control group, the improvement in dyspnea could be related to better adherence to inhaler use. Finally, the trend toward improvement in anxiety in the intervention group might be attributed to better information about the disease, reducing patients’ concerns.

Strengths of the study- 1.

The participants were assigned to intervention and control groups by centers, reducing the risk of contamination.

- 2.

Intervention group investigators were trained in BCTs.

- 3.

The study employed a pragmatic approach.

The main limitation was the reduction in sample size during the study, which may affect the generalizability of the results. This was due to several factors:

- •

Loss of investigators (end of contracts, change of centers or patient populations, long-term leave due to maternity or illness).

- •

Among the remaining investigators, a significant number were unable to recruit patients or carry out interventions due to high clinical demand. To address this limitation, the recruitment period was extended.

This sample size issue is a common challenge in studies on self-care interventions for COPD, as evidenced by other studies:

- •

Gallefoss 199925 (self-care n=27, standard care n=26).

- •

Jonson-Warrington 201626 (self-care n=35, standard care n=36).

- •

Titova 201527 (self-care n=51, standard care n=49).

- •

Sánchez-Nieto 201628 (self-care n=47, standard care n=38).

- •

Jondottir 201529 (self-care n=48, standard care n=52).

The study was initiated before the COVID-19 pandemic (state of emergency in Spain and lockdown from March 14, 2020, to June 19, 2020). This situation impacted the study, leading to the loss of associated investigators and the withdrawal of study patients affected by COVID-19, many of whom discontinued follow-up.

COVID adjustment in resultsAdjusting for the confounding variable “COVID” gave an improvement in SGRQ scores in both the COVID intervention group (CIG) and the non-COVID intervention group (NCIG) compared to their respective control groups, although the differences were not statistically significant. This suggests that the potential confounding effect of COVID-19 does not significantly alter the results.

Factors influencing the limited effectiveness of self-management interventions in COPDSeveral factors might explain why a self-management intervention for COPD is not significantly more effective than usual care:

- •

Patients with moderate–severe COPD have limited “room for improvement” due to their severe functional limitation, suggesting they might benefit more from rehabilitation programs than educational programs.25,26

- •

Elderly patients or those with severe comorbidities may struggle to identify early signs of exacerbation, such as dyspnea or pain.27

- •

Each component of a self-care program has specific effects, making it essential to personalize program assignment and implementation based on patient characteristics.28

- •

Oxygenation deficiencies in COPD patients can impair cognitive function, potentially interfering with their ability to learn and apply self-care programs.29

- •

A more intensive focus on smoking cessation is needed, considering the low adherence of patients to such programs and the understanding of their importance.29,30

The results align with a 2022 systematic review by J. Shrijver et al.,17 which graded the evidence for self-management interventions in COPD as “moderate” to “very low” using the GRADE scale. A study by E. Bischoff et al.31 (a 24-month randomized controlled trial) compared 2 self-management interventions with usual care in COPD patients and found no significant differences in quality of life. The intervention, based on the “Living Well with COPD” program, included education on COPD, medication, breathing techniques, exacerbation management, and exercise, delivered in 1-hour sessions over 4–6 weeks, with telephone reinforcement by a nurse. Outcomes measured included quality of life, exacerbation frequency, and management.

Similarly, a study by K. Jolly et al.32 (a 6-month randomized controlled trial) evaluated the effectiveness of telephone-based self-care promotion in COPD patients in primary care compared to usual care, finding no improvement in quality of life. The study was conducted entirely by telephone, providing intervention group access to smoking cessation, exercise promotion, medication management, and an action plan. Nurses conducting the calls received 2hours of training. The participants were primarily patients with mild COPD.

Lastly, J. Liang et al.33 conducted a randomized controlled trial in primary care comparing a multidisciplinary intervention for COPD patients with usual care, finding no significant differences. The self-management intervention included smoking cessation, home medication reviews, and home-based pulmonary rehabilitation. Primary outcomes included changes in SGRQ, CAT, dyspnea, smoking cessation, and lung function at 6 and 12 months. The study reported an improvement in quality of life in the intervention group, which was not statistically significant.

ConclusionsIn patients with moderate–severe COPD, a structured self-management intervention in primary care with 12 months of follow-up is not more effective than usual care in improving quality of life, dyspnea, inhaler adherence, anxiety, or depression. The following recommendations are suggested:

- •

Conduct studies with larger sample sizes.

- •

Extend the study duration.

- •

Tailor interventions to individual patient needs.

- •

Conduct a qualitative study to analyze participants’ opinions on the intervention and the study overall.

All the patients that participated in the study signed the Informed Consent.

FundingThis study was funded by the Fundació Infermeria i Societat, reference number PR-232/17.

Authors’ contributionMaite López Luque is the principal author of the study. She was responsible for the design and implementation of the study and participated in the writing of the manuscript. Marta Chuecos Molina, Guadalupe Ortega Cuelva, Mª Jesús Vázquez López, Esther Ruiz Rodríguez, Mª Ángeles Santos Santos, Adrià Almazor Sirvent, Antonio Vallejo Domingo, and Toni López Ruiz participated in the study conduct and the writing of the manuscript. Francesc Orfila Pernas is the author responsible for the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results. Nina Granel Giménez advised the corresponding author on manuscript writing. Purificación Jordana Ferrando designed the manuscript and is the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors has received financial compensation for participating in the preparation of this manuscript. MLL has no specific conflicts of interest related to this document; she has received honoraria for lectures and educational and outreach programs from various pharmaceutical companies (Chiesi, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis).

Use of artificial intelligenceArtificial intelligence was not used in the production of the manuscript, references, abstract, figures, or tables.

Becerra Fortes, Ricard

Bote Fernández, Cristina

Chorén Freire, Mª Jesús

Ciges Pereira, Esther

Del Río Català, Miriam

Díaz Trejo, Ainhoa

Elías Briceño, Sonia Mª

Estella Sánchez, Laura

Ferrer Panzano, Rosa

León Llorente, Isidro

Puig Artigas, Ana

Roura Martínez, Luz

Rubio Pérez, Laura

Sánchez Gómez, Carmen

Santiago Fernández, Cristina

Sierra Janeras, Mª Pilar

Sierra Peinado, Verónica

Solsona Tuneu, Marta

Tarancón Egido, Mª Esther

Vicens Català, Adela