Effective communication is the cornerstone of a fruitful patient–physician relationship. Teaching clinical communication has become a pivotal goal in medical education. However, approaches measuring the maintenance of learned skills are needed since a decline in some communication skills during medical school has been reported.

ObjectiveExplore medical students’ communication skills in a simulated clinical encounter before and after clerkships.

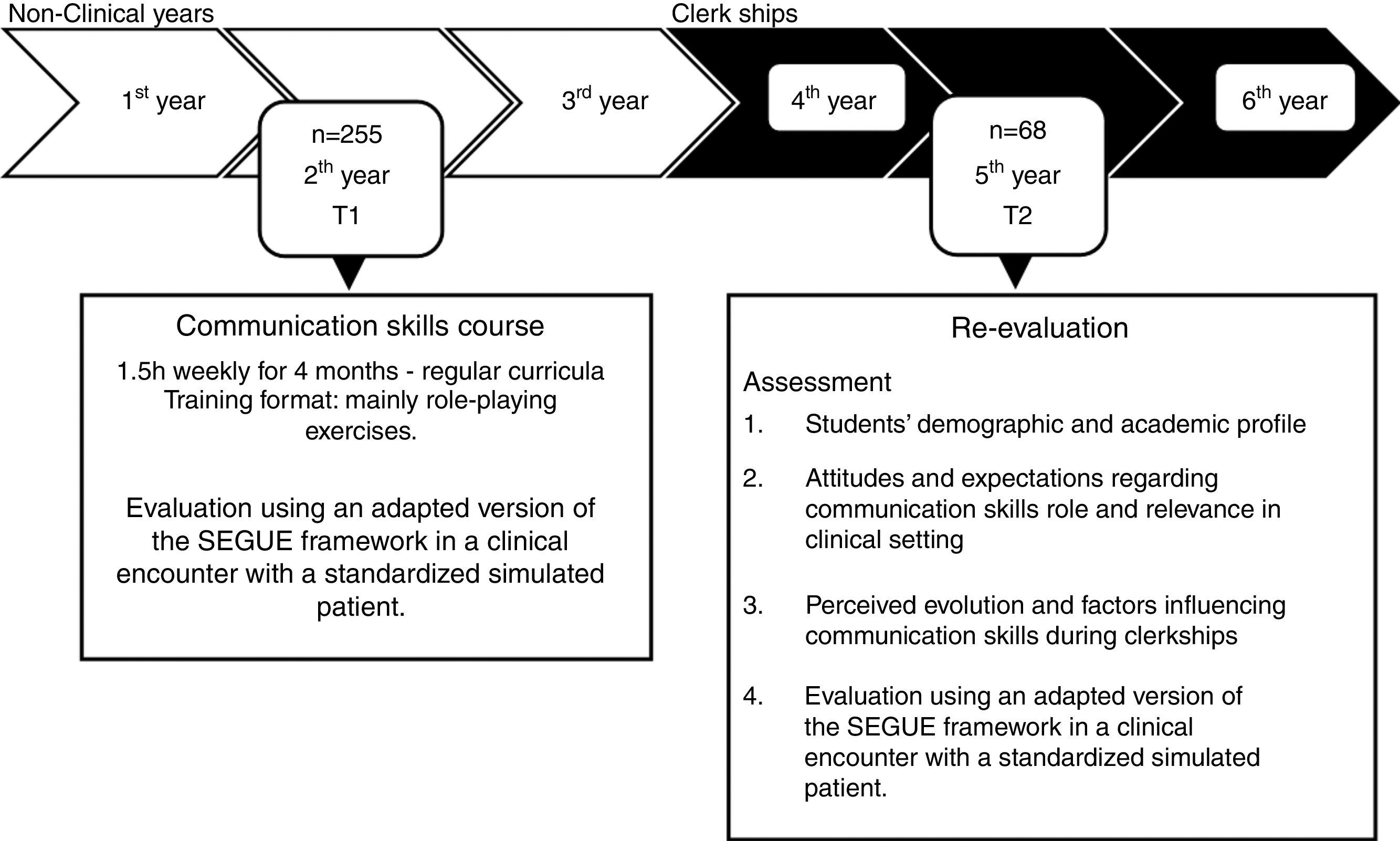

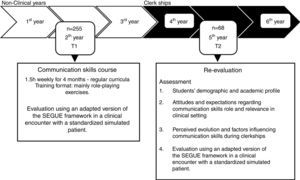

MethodsTwo-hundred-fifty-five undergraduate students attending the second year of medical course, at the Faculty of Medicine of University of Porto, completed a 1.5-h per week course over 4 months on basic communication skills. The students’ final evaluation consisted in an interview with a simulated patient, assessed by a teacher using a standardized framework. Three years later, while attending clerkships, 68 students from the same population completed a re-evaluation interview following the same procedure.

ResultsMedical students maintained a communication skill mean level similar to that of the original post-training evaluation, but significant differences in specific communication abilities were detected in this group of students. Empathic attitudes and ability to collect information improved whereas interview structure and non-verbal behavior showed a decline during clerkships expressing a balance between the competencies that improved, those that declined, and those that remained unchanged.

ConclusionPresent findings emphasize the importance of patient contact, context and clinical role models on the maintenance of learned skills, underscoring the importance of an integrated approach of clinical communication teaching throughout medical school.

Effective communication is the cornerstone of patient-centered medicine and empathic behavior, leading to a fruitful patient–physician relationship. It contributes to a positive therapeutic effect and better patient outcomes and satisfaction, thus increasing the overall quality of health care systems.1–4 Proficient physician communication is identically associated with professional satisfaction, accomplishment, and confidence.5,6

Teaching the why and how of clinical communication has then become a pivotal goal in medical education, gradually included in undergraduate curricula as a means to enhance the ability to collect relevant information, build strong therapeutic relationships, and foster patient care.5,7,8

Experience shows that medical students are attentive, motivated and avidly develop clinical communication skills (CCS) in concert with other medical skills.9–11 Problem-oriented CCS are reported to be easier to teach and learn than empathy or respect, as these require a strong influence of innate emotional and cultural sources.12 Even so, empathy can be taught and improved.13,14

The most suitable and effective time during the medical course to learn CCS is still a matter of debate, with some authors stating that a longitudinal design covering several years could be the more effective.39–41 Students also believe that it is important to learn communication strategies throughout the medical course by integrating them into clinical practice.42

Currently, training programs applied during medical courses have been shown to improve students’ knowledge,43–45 attitudes,46,47 confidence,48,49 empathy,50–52 patient-centeredness,48,49 and interview structure12,44,53,54 and also promote patient satisfaction.48,55,56

Gender has been described to influence CCS acquisition in medical students. Female students were found to be more patient-centered,48,57 to have more positive attitudes toward CCS training,8,11,12,58 to be more empathic59–66 and to be more prone to develop interpersonal relationships.61,67 Male students were described to have less positive attitudes toward CCS learning,9,11 to be more confident68,69 and to frequently adopt attitudes of dominance and independence.70

Assessment of students’ communication skillsThe objective assessment of a student's ability to communicate with patients has also gathered emergent attention.31 Methods to assess the level of “knows” (remembering the skill) and/or “knows how” (applying the skill) of communication can be divided into: video presentations with oral, essay, or multiple-choice exam questions71 and peer and/or self-assessment of communication skills45,72,73; checklists filled by observers of students’ performances during real or simulated patient encounters; surveys of real or simulated patient experience in clinical interactions. Clinical encounters with simulated patients trained to follow standardized scenarios are presently widely used.74 These interviews provide an objective assessment with high validity and reliability, permitting to evaluate how students objectively “do”31 and to obtain the patient's perspective of how efficiently they perform. The same tools have failed to gather a strong consensus regarding empathy.75–77 The cognitive and behavioral dimensions of empathy were found to be more easily validated (e.g., listening carefully and acting accordingly) during a simulated interview than the emotional dimension (e.g., address and respond to emotions).78

Communication skills through clerkshipsPeriodic assessment of retention and application of CCS is of utmost importance to confirm the effectiveness in communicating with patients and the persistence of learned abilities. A decline of CCS during clerkships in undergraduate medical students has been reported, namely in empathy,72,79,80 patient-centered attitudes,57 process-oriented skills,81,82 and attitudes toward the doctor–patient relationship.83,84 Regarding empathy, however, it has recently been argued that the suggested decline among medical students is “greatly exaggerated” because of methodological shortcomings.85 Adding to this dispute, various cross-sectional studies61,63,65,86–88 and two longitudinal studies62,66 on self-reported empathy also showed an increase or no significant variation in empathy during the medical course. CCS learned in the first years of undergraduate medical education can, in fact, be challenged during clinical practice when students are confronted with time constraints, demanding contexts, role models with different communication styles, and real patients.20,89–91 Other factors reported to influence skill retention are: students’ attitudes toward communication skills training and value of clinical communication skills; experience within the clinical setting; specialty preferences; and demographic variables, such as gender and cultural background.48,96–98 Interacting with real patients is also thought to reinforce the students ability to communicate accurately.99 The decline in specific communication abilities can be associated with the lack of articulation of pre-clinical and clinical curricula and the learning context in clinical practice: higher demand of medical training; cultural or organizational influences; marked variability among tutors regarding communication skills; and the gap between academic and clinical role models.72,91,100–103 Role-modeling by clinical teachers has been pointed to by students as the most powerful influence on empathy development.104,105 Negative attitudes from clinical faculty and residents,103 an intimidating educational environment, perception of brittleness, overly demanding educational assignments and patient negativity were reasons proposed to contribute to the decline in empathy during the medical course.106

Our aim was to study how medical students communicate before and after clerkships in a simulated clinical encounter. As secondary aims we intended to: (i) explore students perspective on communication skills relevance and changes during medical school and (ii) identify specific needs in order to refine communication skills teaching.

MethodsThe present study follows an observational longitudinal design.

The medical course at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto runs a six-year undergraduate program divided into pre-clinical years (years 1–3) and clinical clerkships (years 4–6). During the first three years, students have a small clinical experience and a few opportunities to interact with patients. Inversely, during clerkships, they interact with patients within a clinical environment, largely hospital-based, under clinician supervision. Communication skills and the doctor–patient relationship are studied in the second year, including the acquisition of a theoretical background and practical training. Training is based on experiential techniques (role-playing, and videotaped simulated clinical situations) used to establish experience and reflect on communication abilities. The final evaluation consists of a clinical encounter with a trained actor as a simulated patient, which is assessed by teachers using an adapted version of the checklist of medical communication tasks: Set the Stage, Elicit information, Give information, Understand the patient's perspective, End the encounter (SEGUE).75

ParticipantsA convenience sample of 68 students from a pool of 255 students was recruited for the present study, based on a sample size calculation assuming a standard deviation of 4 and a mean difference of 2 between T1 and T2111 (alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 80%). The participants were invited to participate using a snowball approach (phone call, in-person or email contact). Sixty-nine students were contacted and 68 accepted to participate. The inclusion criterion was willingness to participate. No exclusion criteria were applied.

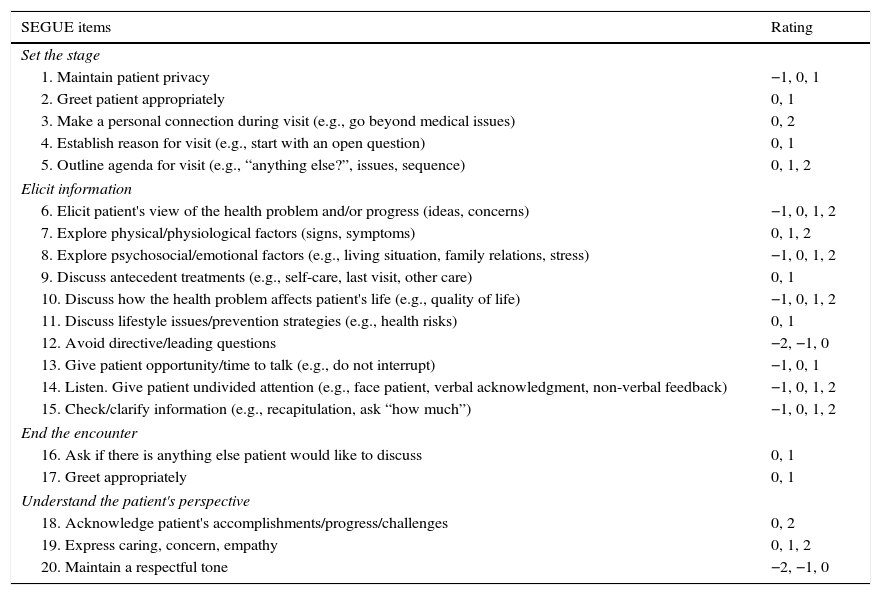

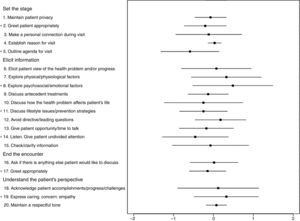

InstrumentsThe SEGUE framework75 was translated and adapted to meet the assessment needs of the teaching program and to discriminate students performance. This adapted version contains 20 items divided into 4 content areas (Set the stage; Elicit information; Understand the patient's perspective; and End the encounter). Items are rated as: 2 for excellent performance; 1 for average performance; 0 for absent performance; −1 for inadequate performance; and −2 directedness or disrespectful tone. This scoring corresponds to the pedagogical outcomes of the course and results from a consensus of communication skills teachers established and in use since 2007. The final score is achieved by the sum of all items. The maximum score is 28 and the minimum is −11. A detailed description of the scale is presented in Table 1.

Score range for each item of the adapted version of SEGUE framework.

| SEGUE items | Rating |

|---|---|

| Set the stage | |

| 1. Maintain patient privacy | −1, 0, 1 |

| 2. Greet patient appropriately | 0, 1 |

| 3. Make a personal connection during visit (e.g., go beyond medical issues) | 0, 2 |

| 4. Establish reason for visit (e.g., start with an open question) | 0, 1 |

| 5. Outline agenda for visit (e.g., “anything else?”, issues, sequence) | 0, 1, 2 |

| Elicit information | |

| 6. Elicit patient's view of the health problem and/or progress (ideas, concerns) | −1, 0, 1, 2 |

| 7. Explore physical/physiological factors (signs, symptoms) | 0, 1, 2 |

| 8. Explore psychosocial/emotional factors (e.g., living situation, family relations, stress) | −1, 0, 1, 2 |

| 9. Discuss antecedent treatments (e.g., self-care, last visit, other care) | 0, 1 |

| 10. Discuss how the health problem affects patient's life (e.g., quality of life) | −1, 0, 1, 2 |

| 11. Discuss lifestyle issues/prevention strategies (e.g., health risks) | 0, 1 |

| 12. Avoid directive/leading questions | −2, −1, 0 |

| 13. Give patient opportunity/time to talk (e.g., do not interrupt) | −1, 0, 1 |

| 14. Listen. Give patient undivided attention (e.g., face patient, verbal acknowledgment, non-verbal feedback) | −1, 0, 1, 2 |

| 15. Check/clarify information (e.g., recapitulation, ask “how much”) | −1, 0, 1, 2 |

| End the encounter | |

| 16. Ask if there is anything else patient would like to discuss | 0, 1 |

| 17. Greet appropriately | 0, 1 |

| Understand the patient's perspective | |

| 18. Acknowledge patient's accomplishments/progress/challenges | 0, 2 |

| 19. Express caring, concern, empathy | 0, 1, 2 |

| 20. Maintain a respectful tone | −2, −1, 0 |

An original questionnaire was built in order to characterize students demographic (age, gender) and academic profile and to define clinical areas of interest. Attitudes and expectations of the students regarding the role of CCS in the clinical setting and their perceived performances in communicating with patients during clerkships were also evaluated. A 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree” was used to rate: clinical communication patterns observed in clinical practice versus the curricular training program, specific suggestions from clinicians, perceived changes in learned competences, and expectation of communication skills usefulness in clinical practice.

Procedures/data collectionAll students of our sample performed a clinical encounter (T2) similar to the final evaluation of the communication skills course (T1), assessed by a trained teacher. This rater participated also at the T1 evaluation. Two actors (one male and the other female) with accredited academic education in social sciences and experience as simulated patients voluntarily agreed to collaborate. The simulated situations and patients were randomly chosen.

The researchers were blind for students T1 score. The interview rater and collector of other data were blind for each other's evaluation. Evaluation procedures are detailed in Fig. 1.

Statistical methodsSPSS Statistics (version 20) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics, means, and standard deviations were calculated for the demographic, academic, and SEGUE results. Chi-square test, Kruskal–Wallis, independent, and paired-samples t-tests were also used to detect statistically significant differences between groups. Significance value p for follow-up differences on SEGUE items was set at 0.0025 according to Bonferroni correction, in order to minimize the family-wise error rate of multiple measurements.

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethical Committee from São João Hospital EPE. Participants were informed about the study and methods and confidentiality was ensured. All participants signed a written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki for human research ethics.

ResultsSocio-demographic and academic characteristicsMean age of participants was 22.7 years (SD 0.63). Twenty-six were males (38.2%) and 42 were females (61.8%). All students had joined medical school in the same year. Academic performance, measured by average course grade, varied between 12.0 and 17.5 in a 20 values range, with a mean result of 14.2 values. Fifty-six students presented “Clinical practice” as their main interest in coming to medicine; 1 indicated “Research”; 6 indicated both reasons; and 5 joined the medical course mainly for research reasons but presently showed clinical practice as their principal interest.

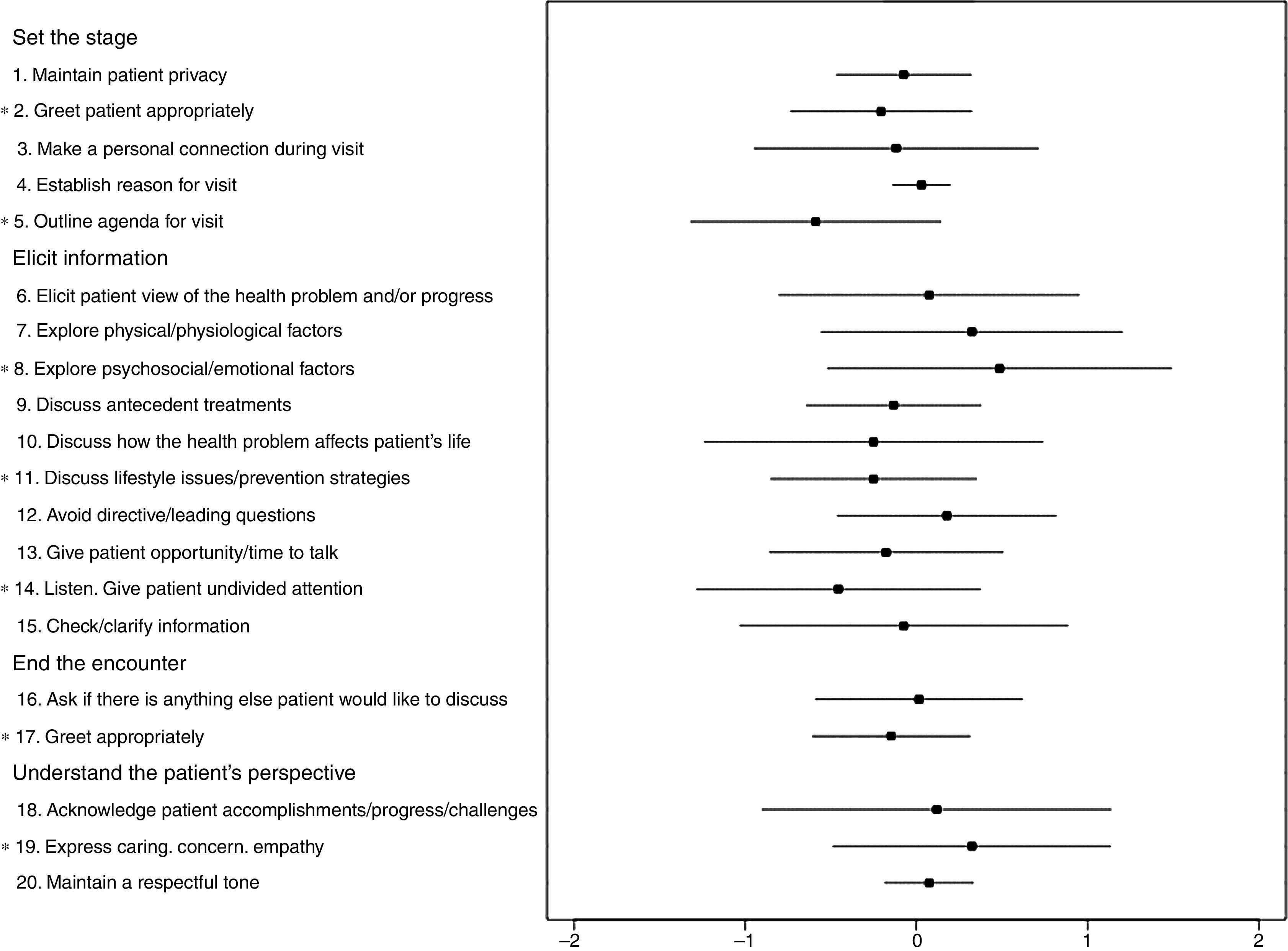

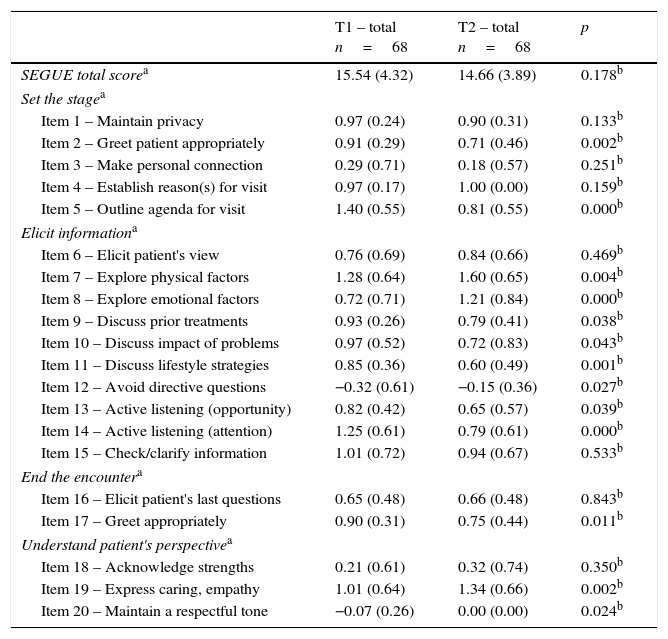

Communication skills assessment before (T1) and after clerkships (T2)Similar results (p=0.178) were obtained in SEGUE framework in the T1 (15.5 SD 4.3) and T2 (14.7 SD 3.9). Detailed analyses revealed statistically significant differences between the two evaluations. The mean score of the items “Explore psychosocial/emotional factors” (p<0.001) and “Express caring, concern, empathy” (p=0.002) were significantly higher in T2. On the contrary, the items “Greet patient appropriately at the beginning of the encounter” (p=0.002), “Outline agenda for visit” (p<0.001), “Discuss lifestyle and prevention strategies” (p=0.001), and “Active listening (undivided attention)” (p<0.001) presented statistically significant lower scores at re-evaluation (see Fig. 2 and Table 2). No gender differences were detected in the SEGUE total mean score and item analysis at T1 and T2 (data not shown).

Follow-up differences on communication skills performance (T1–T2).

| T1 – total n=68 | T2 – total n=68 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEGUE total scorea | 15.54 (4.32) | 14.66 (3.89) | 0.178b |

| Set the stagea | |||

| Item 1 – Maintain privacy | 0.97 (0.24) | 0.90 (0.31) | 0.133b |

| Item 2 – Greet patient appropriately | 0.91 (0.29) | 0.71 (0.46) | 0.002b |

| Item 3 – Make personal connection | 0.29 (0.71) | 0.18 (0.57) | 0.251b |

| Item 4 – Establish reason(s) for visit | 0.97 (0.17) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.159b |

| Item 5 – Outline agenda for visit | 1.40 (0.55) | 0.81 (0.55) | 0.000b |

| Elicit informationa | |||

| Item 6 – Elicit patient's view | 0.76 (0.69) | 0.84 (0.66) | 0.469b |

| Item 7 – Explore physical factors | 1.28 (0.64) | 1.60 (0.65) | 0.004b |

| Item 8 – Explore emotional factors | 0.72 (0.71) | 1.21 (0.84) | 0.000b |

| Item 9 – Discuss prior treatments | 0.93 (0.26) | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.038b |

| Item 10 – Discuss impact of problems | 0.97 (0.52) | 0.72 (0.83) | 0.043b |

| Item 11 – Discuss lifestyle strategies | 0.85 (0.36) | 0.60 (0.49) | 0.001b |

| Item 12 – Avoid directive questions | −0.32 (0.61) | −0.15 (0.36) | 0.027b |

| Item 13 – Active listening (opportunity) | 0.82 (0.42) | 0.65 (0.57) | 0.039b |

| Item 14 – Active listening (attention) | 1.25 (0.61) | 0.79 (0.61) | 0.000b |

| Item 15 – Check/clarify information | 1.01 (0.72) | 0.94 (0.67) | 0.533b |

| End the encountera | |||

| Item 16 – Elicit patient's last questions | 0.65 (0.48) | 0.66 (0.48) | 0.843b |

| Item 17 – Greet appropriately | 0.90 (0.31) | 0.75 (0.44) | 0.011b |

| Understand patient's perspectivea | |||

| Item 18 – Acknowledge strengths | 0.21 (0.61) | 0.32 (0.74) | 0.350b |

| Item 19 – Express caring, empathy | 1.01 (0.64) | 1.34 (0.66) | 0.002b |

| Item 20 – Maintain a respectful tone | −0.07 (0.26) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.024b |

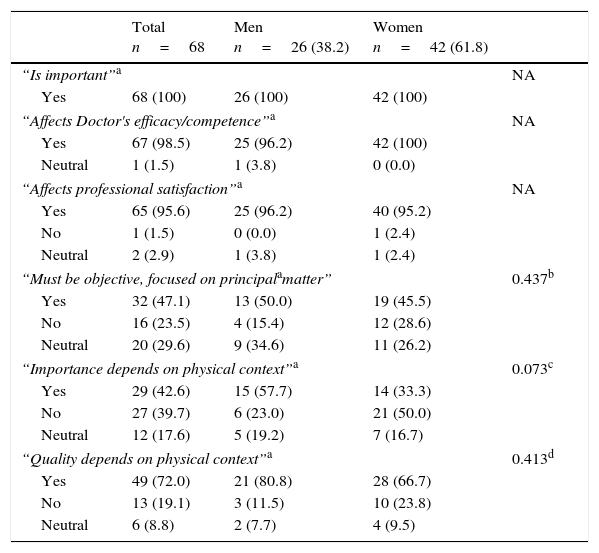

The majority of the students stated that doctor–patient communication “is important” (n=68, 100%), “affects doctor's efficacy/competence” (n=67, 98.5%), and “affects professional satisfaction” (n=65, 95.6%). Concerning the question if communication “Must be objective, focused on principal complaint,” 32 (47.1%) answered positively, 16 (23.5%) disagreed, and 20 (29.4%) had no opinion. Approximately half of the participants declared that communication skills relevance and quality depends on the physical context of doctor–patient interaction (whether the situation occurs in an emergency room, infirmary, or physicians office). No statistically significant gender differences were found (see Table 3).

Students’ general perspective on clinical communication.

| Total n=68 | Men n=26 (38.2) | Women n=42 (61.8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Is important”a | NA | |||

| Yes | 68 (100) | 26 (100) | 42 (100) | |

| “Affects Doctor's efficacy/competence”a | NA | |||

| Yes | 67 (98.5) | 25 (96.2) | 42 (100) | |

| Neutral | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| “Affects professional satisfaction”a | NA | |||

| Yes | 65 (95.6) | 25 (96.2) | 40 (95.2) | |

| No | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Neutral | 2 (2.9) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (2.4) | |

| “Must be objective, focused on principalamatter” | 0.437b | |||

| Yes | 32 (47.1) | 13 (50.0) | 19 (45.5) | |

| No | 16 (23.5) | 4 (15.4) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Neutral | 20 (29.6) | 9 (34.6) | 11 (26.2) | |

| “Importance depends on physical context”a | 0.073c | |||

| Yes | 29 (42.6) | 15 (57.7) | 14 (33.3) | |

| No | 27 (39.7) | 6 (23.0) | 21 (50.0) | |

| Neutral | 12 (17.6) | 5 (19.2) | 7 (16.7) | |

| “Quality depends on physical context”a | 0.413d | |||

| Yes | 49 (72.0) | 21 (80.8) | 28 (66.7) | |

| No | 13 (19.1) | 3 (11.5) | 10 (23.8) | |

| Neutral | 6 (8.8) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (9.5) | |

NA – not applicable.

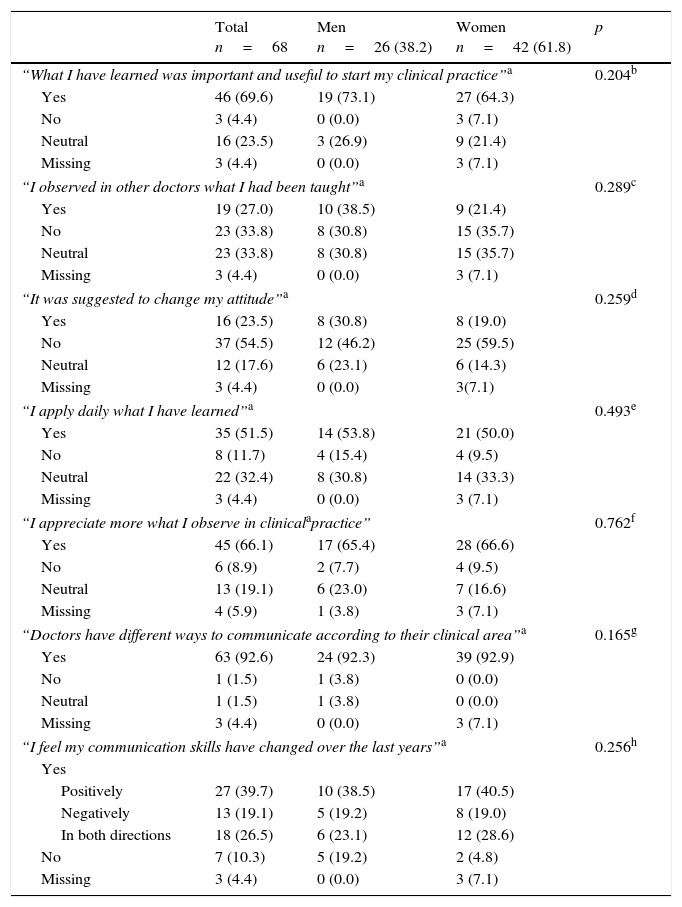

Students stated that learning communication skills was important to their clinical practice (n=46, 67.6%) and approximately half say they apply what they have learned (n=35, 51.5%). However, students report that physicians they work with use different communication strategies (n=46, 70.8%). Clinical context was considered to influence the communicational approach (n=45, 66.1%). From the 58 (85.3%) students who considered their communication skills to have changed over the last years, 27 (46.5%) presently believe they can better communicate with patients, 13 (22.4%) feel that their communication skills declined with clinical practice, and 18 (31.0%) say that their clinical experience has strengthened some skills and weakened others. The main reasons for a positive change were: clinical experience; scientific knowledge; and confidence in communicating with patients and for a negative change were: lack of time; role models with different communication patterns; complex real patients; and complex real context. Almost all students (n=63, 92.6%) noticed that doctors use different ways to communicate according to their clinical area. Regarding future clinical practice, this group of students seems to prefer medical (n=30, 44.1%) or medico-surgical (n=19, 27.9%) areas. No statistically significant gender differences were found (see Table 4).

Students’ evaluation of their communication skills changes.

| Total n=68 | Men n=26 (38.2) | Women n=42 (61.8) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “What I have learned was important and useful to start my clinical practice”a | 0.204b | |||

| Yes | 46 (69.6) | 19 (73.1) | 27 (64.3) | |

| No | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Neutral | 16 (23.5) | 3 (26.9) | 9 (21.4) | |

| Missing | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | |

| “I observed in other doctors what I had been taught”a | 0.289c | |||

| Yes | 19 (27.0) | 10 (38.5) | 9 (21.4) | |

| No | 23 (33.8) | 8 (30.8) | 15 (35.7) | |

| Neutral | 23 (33.8) | 8 (30.8) | 15 (35.7) | |

| Missing | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | |

| “It was suggested to change my attitude”a | 0.259d | |||

| Yes | 16 (23.5) | 8 (30.8) | 8 (19.0) | |

| No | 37 (54.5) | 12 (46.2) | 25 (59.5) | |

| Neutral | 12 (17.6) | 6 (23.1) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Missing | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3(7.1) | |

| “I apply daily what I have learned”a | 0.493e | |||

| Yes | 35 (51.5) | 14 (53.8) | 21 (50.0) | |

| No | 8 (11.7) | 4 (15.4) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Neutral | 22 (32.4) | 8 (30.8) | 14 (33.3) | |

| Missing | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | |

| “I appreciate more what I observe in clinicalapractice” | 0.762f | |||

| Yes | 45 (66.1) | 17 (65.4) | 28 (66.6) | |

| No | 6 (8.9) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Neutral | 13 (19.1) | 6 (23.0) | 7 (16.6) | |

| Missing | 4 (5.9) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (7.1) | |

| “Doctors have different ways to communicate according to their clinical area”a | 0.165g | |||

| Yes | 63 (92.6) | 24 (92.3) | 39 (92.9) | |

| No | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Neutral | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | |

| “I feel my communication skills have changed over the last years”a | 0.256h | |||

| Yes | ||||

| Positively | 27 (39.7) | 10 (38.5) | 17 (40.5) | |

| Negatively | 13 (19.1) | 5 (19.2) | 8 (19.0) | |

| In both directions | 18 (26.5) | 6 (23.1) | 12 (28.6) | |

| No | 7 (10.3) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Missing | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | |

NA – not applicable.

Conflicting results have been reported regarding the changes in learned communication skills during undergraduate medical education.79,81,82,99,107 A reduction in empathy and process-oriented skills has been referred.79,81,82 Others, however, reported that communication skills persist until the last years of the medical course, particularly when experiential training is used as a didactic technique.99

In the present study, a complex pattern regarding the changes in different communication skills was detected. In fact, a number of strategies learned earlier were reinforced with students’ clinical practice, while others showed a significant decline. Interestingly, empathy and ability to gather relevant psychosocial information enhanced after clerkships which is in-line with those who disagree with the “disturbing” conclusion that empathy declines during medical school.66,85 We could speculate that the improvement of empathy in our sample could be related to: the greater clinical experience reported by students that can contribute to a more empathic behavior; a culture influence previously reported in Portuguese students63,66; and contact with empathic role models during clerkships.

A decline was found on some items of interview structure, namely “Outline agenda for visit,” discussion with the patient such as “Discuss lifestyle strategies,” and non-verbal behavior such as “Active listening/giving undivided attention”. Interestingly, a recent follow-up study about the effect of a training program on students’ communication skills found that technical skills (e.g., “greets patients,” “outline agenda”) were easier to learn than other skills.12 Considering that a decline in these abilities was observed, this could highlight that skills learned early in a medical course can be forgotten if not applied and practiced82 and reinforce the importance of integrating communication skills programs throughout medical school.42,120

Students maintained a high ability to protect privacy and establish the reason for the visit. However, attention must be made to the fact that some competencies, such as “Make a personal connection with the patient,” “Elicit patient's view,” “Check/clarify information,” and “Elicit patient's last questions” maintained a similar low score at re-evaluation. This finding points to the difficulty in the acquisition and improvement of these specific abilities, as they seem to be less prone to be acquired after the communication skills training program and also not exercised or amplified during clerkships.

In our study, females showed a tendency for better performance in T1 (immediately after the communication skills curricular program) than males. We may hypothesize that this tendency reflects females more rigorous preparation for the final examination (simulated clinical encounter), since at the second evaluation, a similar total SEGUE score and a similar performance on SEGUE items were found in males and females. Females are stated to be more susceptible to social desirability and exigencies of studying.119 This finding is in-line with previous research stating that female students improve their communication skills the most after training, achieve higher grades in clinical communication tasks118 and have different attitudes toward learning communication skills.11,83 Interestingly, similar empathic ability was detected in males and females both at T1 and T2. These findings are in disagreement with previous research which reported gender differences in acquiring and maintaining communication skills in clinicians and medical students.98,116–118

Students’ perspective on clinical communication and changes in communication skills before and after clerkshipsStudents acknowledged the importance of CCS teaching and training prior to starting their clinical practice, in agreement with other authors.8,42,115 Moreover, students stating that they “apply daily what they have learned” also strengthen the importance of the training program.

Medical students are reported to be attentive and motivated to learn and train clinical communication strategies.11,58 Communication skills learned early in medical courses have proved to enhance students’ abilities to appropriately relate to and communicate with patients during clerkships.5 All the students included in the present study attended a CCS course integrated in the regular curricula. As explained, this training program is practice-based and experiential in order to facilitate skill acquisition and the observation and feedback of peers and teachers.21,113 Students showed their ability to adequately communicate with a simulated patient in a standardized scenario objectively evaluated. Students scored best on process-oriented items than on more empathic ones such as “Make a personal connection with patient,” “Elicit patient's view,” “Explore emotional factors,” “Discuss impact of problems,” “Acknowledge strengths,” or “Express caring, empathy.” These findings are in agreement with the previously reported findings that technical skills are easier to learn and score better after interventions.12

Reports on medical students’ awareness of the relevance of doctor-patient communication as a core professional skill102 underline the importance of communication skills training programs in medical schools. Accordingly, in the present study, the majority of the students agreed that “clinical communication is important and affects doctors’ competence and satisfaction.” However, participants perceived that physical and clinical context could compromise the quality of clinical communication. Time pressure, for example, can influence communicational style; if a lack of time exists, a more straight-to-the-problem communication pattern develops.41 Furthermore, students in our sample stated that “clinical communication must be objective, focused on principal complaint,” probably reflecting a concern with the demanding context of daily clinical practice. The experience of lack of time in clinical settings could also explain students’ lower scores in items such as “discuss lifestyle/prevention strategies” and particularly the decline in their abilities to give patients time and opportunity to express them.

In specific physical contexts (emergency room, infirmary), relevant communication strategies and, consequently, doctor–patient interaction can be compromised.112 This could explain why students learning in those environments may lose some skills in greeting patients appropriately and paying them undivided attention, which is in-line with their statement that the importance of communication skills depends on the physical context. Present findings underscore the weight of context on the applicability of learned skills.91,106

Our study has several limitations. Although the sample size is statistically acceptable and sample characteristics at T2 are similar to the T1 sample regarding gender and academic performance (data not shown), the recruitment method reduces the generalizability of our findings. Because a convenience sample was used students who agreed to participate could be particularly sensitive to the study topic and thus we cannot exclude a selection bias. Also the T1 evaluation was performed by several raters, but only one of them performed the T2 evaluation. We do not consider this to be an important limitation insofar the raters had similar training and experience in using the SEGUE framework for this purpose.

ConclusionThis study used similar conditions regarding interview setting, format, and evaluation in order to compare students performance. The longitudinal design allows characterization of the changes in acquired CCS. The objective evaluation with a standardized instrument of communicational ability allowed to overcome the limitations of subjective self-reports.

This group of students was aware of the importance of clinical communication as a core medical skill and valued the importance of the pre-clerkship communication skills training program. In the years thereafter, students started their clinical practice under the supervision of different clinicians and faced challenges to the previously learned competencies: lack of time; different role models; complex real patients; and complex real context. On the other hand, they reported that clinical experience, higher scientific knowledge, and higher self-confidence contributed to better communicate with patients.

Although students maintained their abilities to communicate similarly to post-training evaluation at second year, a complex pattern regarding the changes in different competencies was detected, suggesting a balance between maintenance, improvement, and decline of CCS. No significant gender differences were found on global communication skills performance in the two evaluations of this cohort assessment.

Practice implicationsThe analysis of which strategies declined, remained steady, and improved during clerkships contributes to refining teaching and training strategies. Present results point to the need to enlarge communication skills teaching and training during clerkships, as some strategies are prone to decline if not applied and practiced in clinical contexts: “Using a helical approach, students can apply the core communication skills learned previously to the new contexts and specialties in which they are learning, while at the same time developing new and advanced skills.”123

Future studies using clinical encounters with real patients are needed in order to permit an evaluation of students communication ability in real contexts.

A baseline evaluation of students before communication skills training would be of interest, making it possible to look for pre-existent factors (personality, gender, socioeconomic status) affecting the acquisition of communication capacities.67,70,83,121

Competing interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The authors are grateful to the medical students and simulated patients (Rita Baptista and Nuno Sá) who kindly agreed to participate in the study. The authors thank Professor Gregory Makoul from the Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center (USA) for permission to adapt the original SEGUE framework. They also would like to acknowledge Professor Rita Gaio from the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Porto for the statistical support, and Sara Rocha, who coded the study material.