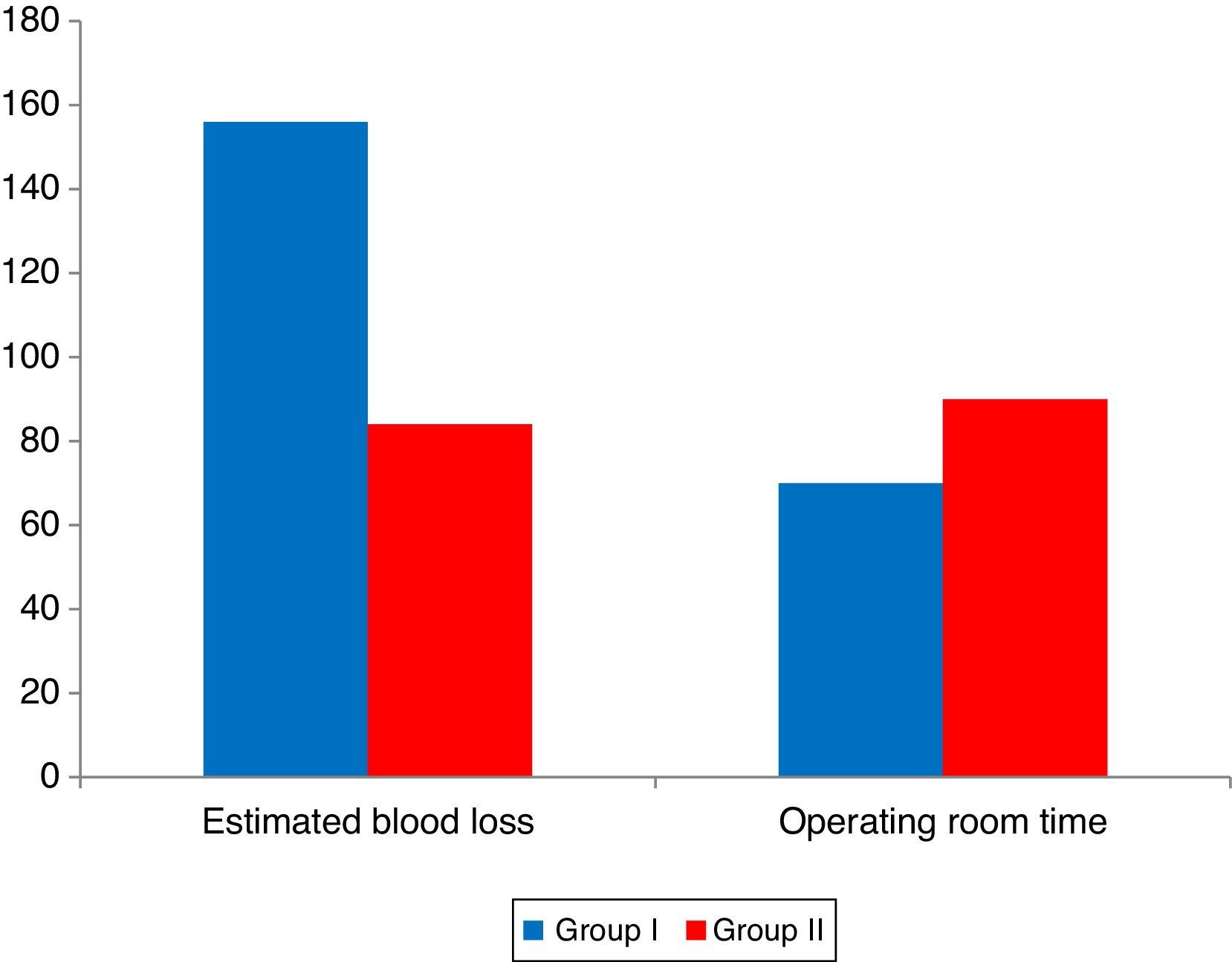

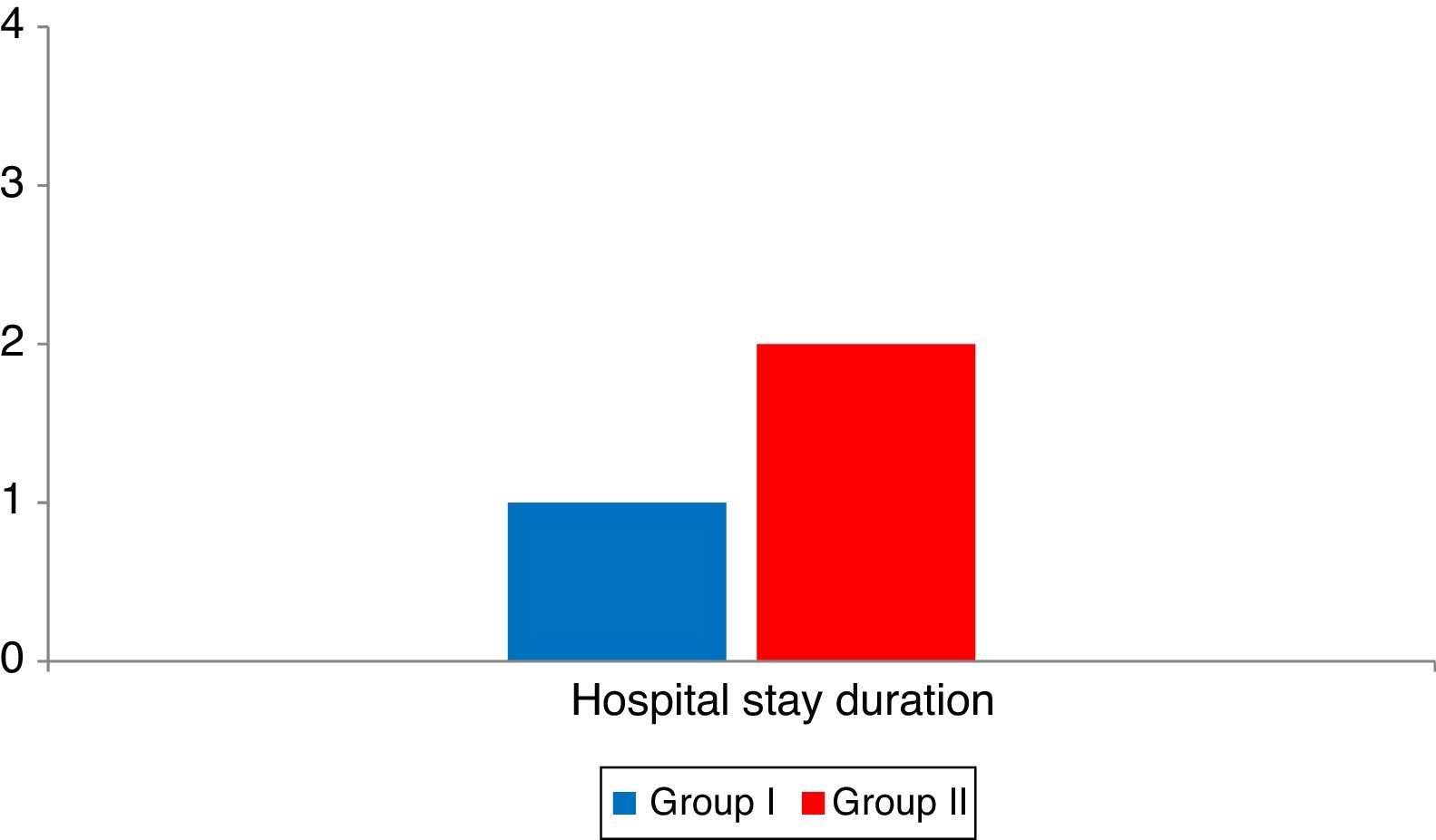

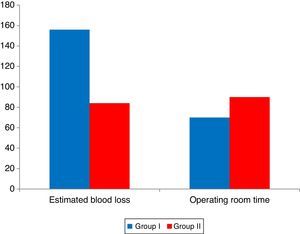

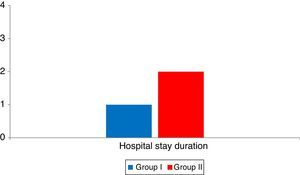

This study was undertaken to compare laparoscopic and open sacral colpopexies for efficacy and safety. This prospective randomized controlled study was conducted in the Gynecologic Department of El-Shatby Maternity Hospital, University of Alexandria in Egypt. It involved 30 women selected after fulfilling the criteria of inclusion into the study with informed consent to participate in the study. All patients in this study were randomly allocated into one of the two following groups: Group A (15 patients) where laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was done. Group B (15 patients) where abdominal (open) sacrocolpopexy was done. Demographic and hospital data, complications, and follow-up visits were reviewed. Median follow-up was 12 months in the laparoscopic and open groups. Mean operating time was significantly greater in the laparoscopic versus open group, 90min and 70min, respectively. Estimated blood loss (84mL vs 156mL) and hospital stay duration (1 vs 2 days) were significantly less in the laparoscopic group than the open group. Demographic data, other perioperative data, quality of life assessment, subjective, objective cure rates, complications and reoperation rates were non-significant. As a conclusion, laparoscopic and open sacral colpopexies have comparable clinical outcomes. Although laparoscopic sacral colpopexy requires longer operating time, hospital stay and blood loss are significantly decreased. Postoperatively overall quality of life and sexual quality showed significant improvement. The subjective cure rate was 90%, the objective cure rate (no prolapse in any compartment) was 100%. The procedure is recommended for experienced laparoscopic surgeons because of severe intraoperative complications like bladder or rectal injuries.

El presente estudio se llevó a cabo para comparar la eficacia y seguridad de las sacrocolpopexias laparoscópicas y de las abiertas. Este ensayo prospectivo, comparativo y aleatorizado se realizó en el Departamento de Ginecología del Hospital de Maternidad El-Shatby, Universidad de Alejandría en Egipto. Se seleccionaron 30 mujeres que cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión y firmaron un consentimiento para participar en la investigación. Las pacientes se dividieron de manera aleatoria en dos grupos: en el Grupo A (15 pacientes) fueron intervenidas mediante colpopexia sacra laparoscópica. En el Grupo B (15 pacientes), mediante colpopexia sacra abdominal (abierta). Se revisaron los datos demográficos y del hospital, las complicaciones y las visitas de seguimiento. La mediana de seguimiento fue a los 12 meses en los grupos laparoscópicos y abiertos. La duración media de la intervención fue significativamente mayor en el grupo laparoscópico frente al grupo abierto, 90 minutos y 70 minutos respectivamente. La pérdida de sangre (84ml frente a 156ml) y la estancia en el hospital (1 frente a 2 días) fueron significativamente menores en el grupo laparoscópico que en el abierto. Los datos demográficos y otra información perioperatoria, la valoración de la calidad de vida, las tasas de curación subjetivas y objetivas, las complicaciones y la tasa de reintervención no fueron significativos. En conclusión, los resultados de las colpopexias sacras laparoscópicas y abiertas son comparables. Si bien la colpopexia sacra laparoscópica precisa un mayor tiempo operatorio, la duración del ingreso y la pérdida de sangre son significativamente menores. La calidad de vida y la calidad sexual postoperatorias mejoraron significativamente. La tasa de curación subjetiva fue de un 90%, la tasa de curación objetiva (sin prolapso en ningún compartimento) fue de un 100%. La técnica quirúrgica se recomienda a cirujanos con experiencia en laparoscopias debido a sus graves complicaciones intraoperatorias, como lesiones vesicales o rectales.

Treatment for uterine prolapse can be either non surgical and surgical. Asymptomatic patients or women who have few minor symptoms may report little or no bother as a result of the disorder. Observation or watchful waiting is appropriate.1 Surgery is indicated when troublesome symptoms persist despite conservative management. The type of surgery should be individualized according to the patient's preference, lifestyle, concomitant disease and age. The first decision is based on whether the patient would like to preserve fertility. Most experts prefer to defer pelvic organ prolapse surgery until childbearing is complete.2

The “gold standard” is abdominal sacral colpopexy. It has the lowest rate of long-term failure of all the procedures. Rates of success (defined as no apical prolapse) with sacral colpopexy range from 78% to 100% and the mean re-operation rate is 4.4%. Sacrocolpopexy is performed by fixation of Prolene mesh to the vaginal walls to the sacral promontory. Mesh supporting the anterior vaginal wall will correct the high cystocele. The posterior mesh extension is taken down as low as possible (Levator ani muscles) to cover the posterior vaginal wall after plication of the rectovaginal fascia. This step treats a rectocele and enterocele at the same time. Complications associated with open sacrocolpopexy include cystotomy 3.1%, enterotomy 1.6% incisional problems 4.6%, ileus 3.6%, thromboembolic event 3.3% and transfusion 4.4%. Presacral bleeding is the most concerning intra-operative complication and can have life-threatening consequences. Long-term complications include urinary incontinence, voiding dysfunction, De novo other sites prolapse and mesh erosion.3

Retaining the cervix at prolapse surgery may be advantageous in offering a physiologic corner-stone for attachment of the pubocervical fascia, rectovaginal fascia and uterosacral–cardinal ligament complex. This procedure is indicated in young patients with uterine prolapse who do not have children, or who want more children, or patients who refuse a hysterectomy and wish to retain their uterus with normal cervix.4

Unfortunately, surgery has a significant failure rate and in the longer term is associated with a recurrence rate of 25–30%. The aim of using mesh in prolapse repair surgery is to provide additional support and reduce risk of recurrence, especially in women with recurrent prolapse or those with connective tissue disorders. The ideal mesh should be biocompatible, inert, inexpensive, induce minimal inflammatory response and, at the same time, act as a scaffold to facilitate fibrous tissue ingrowth, be resistant to infection, avoid shrinkage and be easy to handle.5

A recent Cochrane review stated that abdominal sacrocolpopexy is the most effective procedure and is considered by many authors to be the gold standard in the treatment of vaginal vault prolapse. Conversely, vaginal prolapse repairs are often faster and offer patients a shorter recovery time.6 Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy aims to bridge the gap between the abdominal and vaginal procedures to provide the best outcomes of abdominal sacrocolpopexy with decreased morbidity similar to vaginal procedures.7

Laparoscopic access and techniques have been applied to most abdominal route surgical procedures for treatment of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. In the decade since Nezhat et al. reported the first series of laparoscopic abdominal sacral colpopexy, the application of this surgical procedure has increased and has recently advanced to robotic-assisted techniques.8 However, widespread adoption of laparoscopic sacral colpopexy has not ensued most likely because of lack of advanced laparoscopic skills resulting from inadequate experience in laparoscopy in residency and fellowship programs; the steep learning curve of laparoscopic suturing likely associated with increased operative time and cost; and surgeon preference of vaginal route procedures for surgical treatment of vaginal apex prolapse.9–12

The literature regarding laparoscopic sacral colpopexy is sparse and devoid of comparative studies. In our study, we evaluated effectiveness of laparoscopic sacrocervicopexy, with or without colporraphy, to resolve pelvic organ prolapse and reduce the recurrence rate, mainly of central compartment prolapse.

This present randomized study compared abdominal sacrocoplopexy and laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) to demonstrate the role of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.

MethodsThis prospective randomized controlled study was conducted in the Gynecologic Department of El-Shatby Maternity Hospital, University of Alexandria in Egypt. It involved 30 women selected after fulfilling the criteria of inclusion into the study with informed consent to participate in the study after approval of the ethics committee. With Inclusion criteria: Grade III or IV (severe) uterovaginal prolapse according to the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) with almost complete eversion of the total length of the vagina or the cervix is protruding through the vulva and beyond with normal cervical length, Uterine prolapsed, normal uterus and ovaries on ultrasound examination, normal menstrual bleeding pattern (if premenopausal) and normal Pap smear. And Exclusion criteria: Inability to give informed consent or to return for follows up, unable to undergo general anesthesia, prior sacral colpopexy, patients presenting with lower grade prolapsed, genuine stress incontinence and indication for hysterectomy. All patients in this study were randomly allocated by opaque sealed envelope method into one of the two following groups: Group A: (15 patients) where laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was done. Group B: (15 patients) where abdominal (open) sacrocolpopexy was done.

The following data were collected preoperative: Patient demographics as age, parity, body mass index, menopausal status, previous surgical procedures, previous gynecological procedures and prolapsed-related symptoms and history of medical or surgical treatments as cardiovascular disorders, thyroid dysfunction, diabetes mellitus and hysterectomy.

All patients were subjected to:

- •

Physical examination: preoperative physical examination was performed in the supine position with the Valsalva maneuver. Genital prolapse was staged according to the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) as described by the International Continence Society by a gynecologist with consistent experience, pre-operative Pap smear. and preoperative urodynamic study (cystometry).

- •

All operations took place under general anesthesia with a Foley catheter in the bladder. Perineaoraphy was done if needed at the end by the conventional vaginal technique. Vaginal procedures were avoided in case of POP-Q score of 0 and 1 for anterior or posterior compartment. The sigmoid colon was reflected as far as possible into the left lateral pelvis to expose the sacral promontory. A retroperitoneal approach was used in all cases. All structures at risk during this portion of the procedure—namely, the common iliac vessels, ureters, and middle sacral artery and vein were identified. The left common iliac vein was medial to the left common iliac artery and was particularly susceptible to injury during this phase of the procedure. An incision was made in the posterior peritoneum over the sacral promontory and delicate sharp and blunt dissection was used to expose the anterior longitudinal ligament which overlying the sacrum (S1). The peritoneal incision was extended inferiorly along the right lateral aspect of the rectum till reaches the upper part of the vagina at the site of the attachment of the uterosacral ligaments. Fixation of the mesh to the back side of the cervix in the implantation of the uterosacral ligaments in the uterus by single Prolene suture and there was peritonización on the fixing area of the cervix attachment. Two permanent prolene #0 sutures were placed through anterior longitudinal ligament at the level of S1. A 10*3cm prolene mash was used to join the back of the cervix and the uterine ends of the uterosacral ligaments to the sacral promontory (using No. 0 prolene suture) providing elevation of the uterus and vagina without tension. After the suspension, the extra mesh was shortened. Mesh fixation was not performed in any case at the levator ani bilaterally to avoid extensive dissection, pain, nerve interuption and low incidence of rectocele. The posterior peritoneum was closed over the mesh using 2–0 vicryl suture. Haemostasis was secured and the abdominal incisions were closed. Where laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was done where the following was done in addition to the previous steps: (98–100) Patients were placed in the semilithotomy position, which allowed both vaginal and laparoscopic access. A uterine manipulator was placed into the uterus. Pneumoperitoneum was created using a Veress needle, and a 10-mm trocar was inserted into the umbilicus, two 5-mm trocars were placed lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels, and one 10-mm trocar was placed medially in the suprapubic area. With the patient in the Trendelenburg position, the procedure began using bipolar forceps for coagulation and a monopolar hook for cutting. The wide-pore polypropylene mesh was introduced through the axillary or the main port. The mesh suturing and peritonisation was done using an intracorporeal knot-tying technique.

- •

Where abdominal sacrocolpopexy was done through Pfannenteil abdominal incision.

The following data were collected peri-operative: Operating room time, inpatient days, estimation of blood loss using the following a modification of Gross formula.13 Recurrence of prolapse. As described in the literature,14 we consider “surgical failure” to be any grade of recurrent prolapse of stage II or more of the POP-Q test and curation as no persistent symptoms or prolapse findings more than 50% of the initial. Intra- and postoperative complications as recurrent or the de novo stress urinary incontinence. Patients with stress urinary incontinence during urodynamic testing underwent the tension free vaginal tape procedure (TOT). Pelvic floor prolapse quality of life questionnaire (short form 7) or satisfaction by VAS score1–10 according to patient‘s compliance.15,16 and Follow-up as regards satisfaction, complications and examination according to POP-Q system.

ResultsOnly 8 cases were postmenopausal in group I (laparoscopy) and 12 in group II (laparotomy). There was no significant difference between both groups. There were 4 complains that were reported from the patients. Mass protruding from the vulva in 8 patients, pelvic heaviness in 3 patients, vaginal swelling in 7 patients in each of the groups. Urine retention in 3 patients in group I and two patients in group II. There were no significant difference between groups as regards complain.

The C point preoperative in the laparotomy group ranged from (+3.0) to (+10.0) with a median of +5, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from (+4.0) to (+10.0) with a median of +7. There was no significant difference between both groups. Postoperatively, we defined the patient as objectively cured if according to the ICS classification7 there was no evidence of prolapse (Stage 0) in any compartment. The C point in the laparotomy group ranged from (−8.0) to (−10.0) with a median of −9.0, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from (−7) to (−10.0) with a median of −9.0. There was no significant difference between both groups.

Stage of uterine prolapse in the laparotomy group ranged from 3 to 4 with a median of 4, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from 3 to 4 with a median of 4. There was no significant difference between both groups. All patients were symptomatic. Stage of cystocele in the laparotomy group ranged from 0 to 3 with a median of 0, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from 0 to 1 with a median of 0. There were 3 cases in group I and 4 in group II. There was no significant difference between both groups. The cases were asympytomatic in stage 0 and 1. Stage of rectocele in the laparotomy group ranged from 0 to 2 with a median of 0, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from 0 to 1 with a median of 0. There were 2 cases in each group. There was no significant difference between both groups. The cases were asymptomatic in stage 0 and 1.

Cystocele repair was performed in 3 cases in group I and perineoraphy for one case with gaped introitus with no cases in group II. There was no significant difference between groups. The repairs were performed using prolene mesh.

The QOL questionnaire score in the laparotomy group ranged from 65 to 100 with a mean of 88, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from 65 to 100 with a mean of 80. There was no significant difference between both groups. The questionnaire score postoperative in the laparotomy group ranged from 0 to 14 with a mean of 7, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from 0 to 15 with a mean of 8. There was no significant difference between both groups.

The VAS score in the laparotomy group ranged from 7 to 10 with a mean of 9, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from 7 to 10 with a mean of 8. There was no significant difference between both groups. The VAS score postoperative in the laparotomy group ranged from 0 to 3 with a mean of 0, while in the laparoscopy group, it ranged from 0 to 2 with a mean of 0. There was no significant difference between both groups. According to these results, we had a subjective cure rate of 90%, an objective cure rate of 100% (over follow-up of 12 months). Cure was defined as a VAS of <2. Improvement was defined as a greater than 50% improvement in VAS from baseline.

There were 2 cases with wound infection in group I that developed on the first week after surgery and managed conservatively with antibiotics, one case with dyspareunia in group II and one case in each group with low back pain that developed in the third month after surgery and managed conservatively that were resolved over time. There were no significant difference between both groups. Postoperative stress urinary incontinence occurred one month after surgery that was confirmed by cystometry where there were 2 cases in group II and one case in group I. A secondary TOT procedure was performed 12 weeks after primary surgery and all of these patients were cured from stress urinary incontinence without any micturition disorders. There were no significant difference between groups.

DiscussionThe abdominal approach has been reported to be superior to the vaginal method regarding outcome3,17,18 and functionality, especially sexual activity. Because of the higher morbidity of the abdominal approach many surgeons still prefer the vaginal approach. Both the Cochrane collaboration and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE, UK) have recommended abdominal sacrohysterocolpopexy with mesh as the optimal surgical treatment for uterovaginal prolapse.19,20 Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy combines the advantage of the abdominal approach with low postoperative morbidity. The advances in laparoscopic techniques since first reported in 199421 and the better vision of the lower pelvis lead to improvement in functional results. But the lack of randomized controlled trials, makes it difficult to decide, which technique is superior. Many published studies on laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy are retrospective and only a few prospective studies evaluate anatomical results of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy using the POP-Q system.22

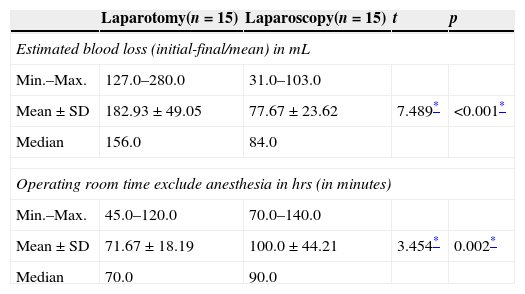

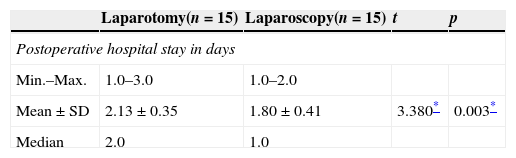

The laparoscopic sacral hysterocolpopexy required a significantly longer operating room time (a median of 90min) in comparison with the open sacral colpopexy in our hands (a median of 70min). However, the patients in our laparoscopic group had a hospital stay that was significantly shorter (a mean differential of 1 day) than that of the open group (2 days). We did not evaluate hospital cost in our study, we can assume that the cost of a longer hospital stay in laparotomy group may be offset by the cost attributed to the longer operating room time in the laparoscopy group. Laparoscopic sacral hysterocolpopexy may result in a cost savings if the operating room time decreases with a short hospital stay.

The steep learning curve associated with laparoscopic suturing in laparoscopic sacral colpopexies is the rate limiting factor of widespread adoption of this surgical procedure. This learning curve increases operative time early in a surgeon's experience and only decreases with increase in number of cases.23

In our series of laparoscopic and laparotomy sacral colpopexy, there were zero cases with cystotomies, bladder sutures or rectal injuries. Patients who have had previous repairs and vaginal route apical suspensions often have extensive adhesions and distorted tissue planes so liable for complications. In laparoscopic surgery, dissection is performed with visualization of tissue planes and without tactile sensation of the surgeon's fingers. Bladder injury is more common early in the primary surgeon's learning curve. It is preferable and less morbid to recognize any organ injury at the time of surgery. Use of electrosurgery is more common during laparoscopic surgery, which is associated with the risks of visceral injury resulting from direct and capacitive coupling of current. We tried to minimize the use of monopolar cautery during our cases and use bipolar cautery in the majority of the time. We had no conversions to laparotomy.

We attempted to attach the mesh to the same extent on the posterior cervical wall in both laparoscopic and open sacral hysterocolpopexies. There were no cases with recurrence. The location of failures usually occurred between the inferior border of the mesh and the apex of the posterior repair. Recurrences may be technique related if the posterior mesh was placed under too much tension thus leaving the segment below the mesh vulnerable to increases in intrabdominal pressure or loose attachment to the cervix. There were no mesh erosions over 12 month follow up.

Using the POP-Q system pre- and postoperatively, we demonstrated an overall objective cure rate of nearly 100% in both groups with no recurrent cases.

Two patients had constipation three month after surgery that was treated conservatively with laxatives and resolved over months. We could demonstrate that the patients’ overall quality of life was significantly improved postoperatively. Using the POP-Q system pre- and postoperatively, we demonstrated an overall objective cure rate of 100% and the subjective cure rate of nearly 90% using questionnaire and VAS score. This showed that laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy is an excellent procedure to resolve prolapse symptoms in a short time follow-up. We also could demonstrate that sexual activity after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was improved and that de-novo dyspareunia is low and improved with time (one case in our study).

In our study, 13% of all patients in open group and 7% in laparoscopy group required further surgery for postoperative urinary incontinence. None of these patients had signs of stress urinary incontinence in the preoperative clinical or urodynamic evaluation. We used cystometry for diagnosing stress incontinence with clinical findings. Our results (postoperative urinary disorders) should be interpreted taking into consideration the epidemiological data of our patients, especially the fact that some patients had prior and concurrent pelvic surgeries for prolapse or incontinence.

Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy had a positive effect on the prolapse-related complaints such as avoidance of sex because of vaginal bulge, incontinence during sexual activity and fear of incontinence. Although prolapse is not typically linked to pain, the discomfort during intercourse could be perceived as pain by some women, which could explain the postoperative improvement. We typically do not perform posterior repairs because the posterior compartment is addressed laparoscopically with a deep dissection aiming to reach the level of the perineal body. The use of perineorrhaphy was reserved for patients with a gaping introitus, and bringing the bulbocavernosus and transverse perinei muscles together did not produce persistent dyspareunia at 1 year.

A randomized trial comparing laparoscopic to abdominal sacrocolpopexy performed by Freeman et al. showed significantly less blood loss (56 versus 240mL), less mean Hb drop (1.12 versus 2.33mg/dL) and shorter hospital stay (3.2 versus 4.1 days) in the laparoscopic group. There was no significant difference in complication rate, but in the abdominal group more severe complications occurred.24 Our trial agreed with these findings.

Also, our trial agreed with the nonrandomized cohort studies of Paraiso et al.25 and Klauschie et al.26 that showed less blood loss and a significantly shorter hospital stay in the laparoscopic group.27 There was no difference in complication rate in both studies. Klauschie et al.26 described one severe bowel obstruction in the abdominal group. In the study of Paraiso et al.25 two patients developed an ileus in the abdominal group, small bowel obstructions occurred once in the laparoscopic group and twice in the abdominal group and one patient of the laparoscopic group, had severe constipation postoperatively. Freeman et al.28 showed de novo urinary incontinence in both groups, mainly in the abdominal group (2 versus 4 patients) which matches to our study results. In contrast with other studies comparing laparoscopic to abdominal sacrocolpopexy,26,29,30 no mesh erosion has been seen in our study population. Patients should be informed preoperatively about complications that occur in more than 5%. This means that constipation and urinary incontinence should be added to the counseling prior to a sacrocolpopexy.

Paraiso et al.31, evaluated 56 patients who underwent laparoscopic sacral colpopexy and 61 patients who underwent open sacral colpopexy. Mean follow-up was 13.5G 12.1 months and 15.7G 18.1 months in the laparoscopic and open groups, respectively. Mean operating time was significantly greater in the laparoscopic versus open cohort, 269min and 218min, respectively. Estimated blood loss (172mL vs 234mL) and hospital stay (1.8 days vs 4.0 days) were significantly less in the laparoscopic group than the open group. Complication and reoperation rates were similar. These findings agreed with ours.32 Also our findings agreed with the previous study. Our lower time may be attributed to our sample size (Figs. 1 and 2).

Our results agreed with those of prospective studies by Gadonneix et al.33 and Ross et al.34 evaluating laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy and abdominal sacrocolpopexy as regard cure rates.35,36 Also our results agreed with other studies evaluating laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy that reported dyspareunia rates between 5% and 38%.37 Because of these findings, we think that laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy should be proposed especially to young sexual active women suffering from apical compartment prolapse.

Nezhat et al.38 reported a series of 15 subjects who underwent laparoscopic sacral colpopexy with follow-up ranging from 3 to 40 months. Mean operative time was 170min (range 105–320) and mean blood loss was 226mL (range 50–800). That was more than our study that may be related to improvement in providers and surgical practice since 1994. The mean hospital stay was 2.3 days as our results, excluding a case converted to laparotomy for presacral hemorrhage. The authors reported a 100% cure rate for apical prolapse as our results. Lyons39 reported 4 laparoscopic sacrospinous fixations and 10 laparoscopic sacral colpopexies with operative times “comparable to vaginal and abdominal approaches.” He attributed less intraoperative and postoperative morbidity to a “superior anatomic approach and visualization of anatomic structures” by laparoscopic route.

A possible reason for the zero rate of rectal and bladder injuries, could be the fact that in contrast to other series,40 we attached the mesh to back of cervix with no need of dissection of rectovaginal space, skill of operator and limited sample size. The high percentage of prior vaginal prolapse surgery in our patients could not alter the results.

Postoperative stress incontinence is higher than in other publications evaluating laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.41,38 We can only assume that the demographic data as regards a high percentage of pre-operated women and a higher median age of 58 years in our study may be a reason for this result with the small sample size. Our size was mainly aimed to show the effect on duration of operation, hospital stay and blood loss. There are many studies demonstrating the feasibility of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy but most of them are retrospective.42

Laparoscopic experience with POP has advanced tremendously, and LSC results from >1000 patients in 11 series support this. Conversion rates and operative times have decreased with increased experience. Mean operative time was 158min (range: 96–286min) with a 2.7% conversion rate (range: 0–11%) and a 1.6% early reoperation rate (range: 0–3.9%). With a mean follow-up of 24.6 month (range: 11.4–66 month), there was, on average, a 94.4% satisfaction rate, a 6.2% prolapse reoperation rate, and a 2.7% mesh erosion rate. Several centers have demonstrated that excellent outcomes with LSC are reproducible in terms of operative parameters, durable results, minimal complications, and high levels of patient satisfaction.43

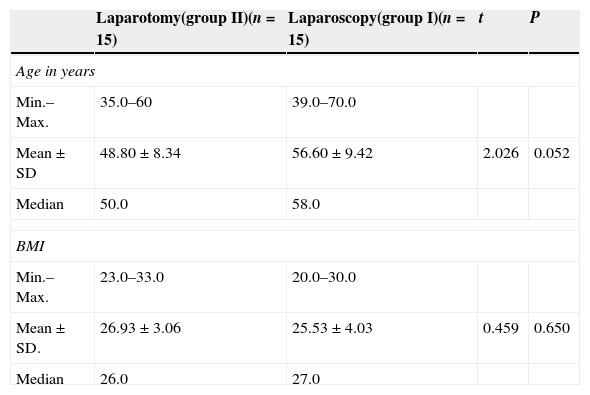

The strength of this study is that it was a prospective and comparative study of identical procedures performed by two routes. Our investigation demonstrated that laparoscopic and open sacral colpopexies have comparable clinical outcomes. Because of our relatively small sample size, we were unable to comment definitively on differences in complications between the 2 procedures (Tables 1–5).

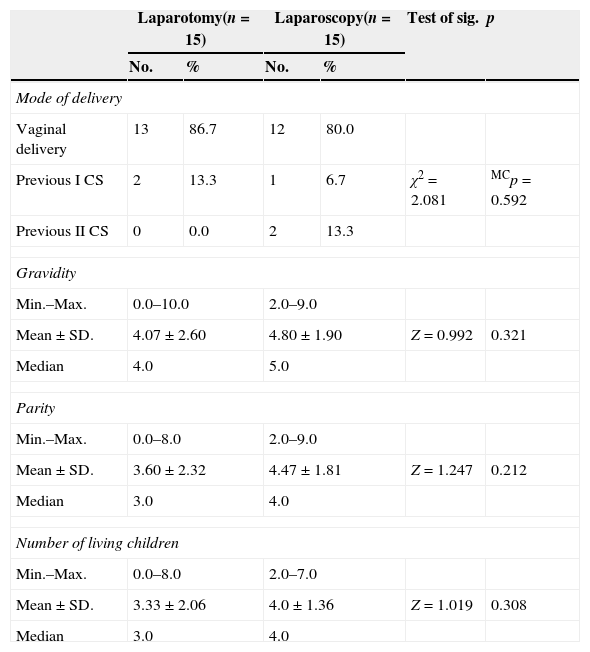

Comparison between the studied groups according to demographic data.

| Laparotomy(group II)(n=15) | Laparoscopy(group I)(n=15) | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||

| Min.–Max. | 35.0–60 | 39.0–70.0 | ||

| Mean±SD | 48.80±8.34 | 56.60±9.42 | 2.026 | 0.052 |

| Median | 50.0 | 58.0 | ||

| BMI | ||||

| Min.–Max. | 23.0–33.0 | 20.0–30.0 | ||

| Mean±SD. | 26.93±3.06 | 25.53±4.03 | 0.459 | 0.650 |

| Median | 26.0 | 27.0 | ||

t: Student t-test.

Comparison between the studied groups according to obstetric history.

| Laparotomy(n=15) | Laparoscopy(n=15) | Test of sig. | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 13 | 86.7 | 12 | 80.0 | ||

| Previous I CS | 2 | 13.3 | 1 | 6.7 | χ2=2.081 | MCp=0.592 |

| Previous II CS | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 13.3 | ||

| Gravidity | ||||||

| Min.–Max. | 0.0–10.0 | 2.0–9.0 | ||||

| Mean±SD. | 4.07±2.60 | 4.80±1.90 | Z=0.992 | 0.321 | ||

| Median | 4.0 | 5.0 | ||||

| Parity | ||||||

| Min.–Max. | 0.0–8.0 | 2.0–9.0 | ||||

| Mean±SD. | 3.60±2.32 | 4.47±1.81 | Z=1.247 | 0.212 | ||

| Median | 3.0 | 4.0 | ||||

| Number of living children | ||||||

| Min.–Max. | 0.0–8.0 | 2.0–7.0 | ||||

| Mean±SD. | 3.33±2.06 | 4.0±1.36 | Z=1.019 | 0.308 | ||

| Median | 3.0 | 4.0 | ||||

Z: Z for Mann–Whitney test.

χ2: Chi square test.

MC: McNemar's test.

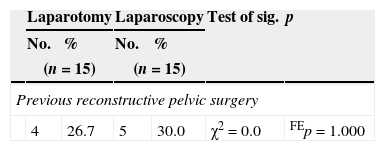

Comparison between the studied groups according to previous reconstructive pelvic surgery.

| Laparotomy | Laparoscopy | Test of sig. | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| (n=15) | (n=15) | |||||

| Previous reconstructive pelvic surgery | ||||||

| 4 | 26.7 | 5 | 30.0 | χ2=0.0 | FEp=1.000 | |

| Laparotomy | Laparoscopy | Test of sig. | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| (n=4) | (n=5) | |||||

| Type of reconstructive pelvic surgery | ||||||

| Sacrospinous ligament fixation | 2 | 50.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0.533 | FEp=1.000 |

| CRC repair | 2 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4.800 | FEp=0.143 |

| Cystocele repair | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 1.143 | FEp=1.000 |

| Rectocele repair | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 2.667 | FEp=0.429 |

t: Student t-test.

χ2: Value for chi square.

FE: Fisher Exact test.

Comparison between the studied groups according to blood loss and duration of surgery.

| Laparotomy(n=15) | Laparoscopy(n=15) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated blood loss (initial-final/mean) in mL | ||||

| Min.–Max. | 127.0–280.0 | 31.0–103.0 | ||

| Mean±SD | 182.93±49.05 | 77.67±23.62 | 7.489* | <0.001* |

| Median | 156.0 | 84.0 | ||

| Operating room time exclude anesthesia in hrs (in minutes) | ||||

| Min.–Max. | 45.0–120.0 | 70.0–140.0 | ||

| Mean±SD | 71.67±18.19 | 100.0±44.21 | 3.454* | 0.002* |

| Median | 70.0 | 90.0 | ||

t: Student t-test.

Clinical outcome of laparoscopic sacral colpopexy were comparable to open sacral colpopexy in our hands. The increase in operative time may elevate the cost of the procedure especially early in the learning curve of the surgeon. Prospective clinical trials and long-term follow-up are warranted.44,45

It has to be stated that operating time and complication rate are extremely dependent on the experience of the surgeon. In our opinion, the laparoscopic approach is not only a means for access to the abdomen but has significant advantages to open surgery. It gives a better view and is an atraumatic surgical technique without compromising the outcome.

A surgeon should choose patients with isolated vaginal apex prolapse for primary cases. It is optimal if he/she receives assistance from a surgeon who is experienced in advanced laparoscopic surgery, particularly laparoscopic sacral colpopexy. Reconstructive pelvic surgeons who have the expertise in laparoscopic sacral colpopexy may offer this alternative route to patients who desire minimally invasive surgery and are candidates for abdominal sacral colpopexy and laparoscopic surgery.46–48

ConclusionsLaparoscopic and open sacral colpopexies have comparable clinical outcomes with very low rates of complications. Although laparoscopic sacral hysterocolpopexy requires longer operating time, hospital stay duration and blood loss are significantly decreased. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy should be performed by experienced laparoscopic surgeons and in experienced institutions as serious intraoperative complications like bladder or rectal injuries may occur. Laparoscopic sacral hysterocolpopexy may result in a cost savings if the operating room time decreases with a short hospital stay.

The steep learning curve associated with laparoscopic suturing in laparoscopic sacral colpopexies is the rate limiting factor of widespread adoption of this surgical procedure. This learning curve increases operative time early in a surgeon's experience and only decreases with increase in number of cases. It is optimal if a young surgeon receives training from an experienced surgeon in laparoscopic sacral colpopexy in his early cases. Reconstructive pelvic surgeons who have the expertise in laparoscopic sacral colpopexy may offer this alternative route to patients who desire minimally invasive surgery and are candidates for abdominal sacral colpopexy and laparoscopic surgery. More prospective studies with a long-term follow-up more than 12 months are needed to evaluate the long-term outcomes of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestAhmed El-agwany, Tamer Hanafi, Ahmed Nagaty, Hisham Salem Abdelfatah declare that they have no conflict of interest All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.