This study assessed the effectiveness of an intervention designed to foster more positive attitudes towards persons with mental illness among college students in Delhi. A total of 50 young people participated in a one-time education and contact based intervention. Attitudes towards persons with mental illness were assessed before the intervention, immediately after it and at a one week follow-up. Results indicated increased feelings of benevolence, community mental health ideology and less authoritarianism at the post-intervention assessments. Reduction in endorsement of social restrictiveness was also observed but only in the case of the immediate post-assessment. We also observed a greater recognition of needs, increased positive descriptions, decreased negative descriptions and reduced labelling after the intervention. These results support the efficacy of education and contact-based strategies for reducing mental illness stigma. Implications of the findings for low-middle income countries like India are discussed.

El estudio valoró la eficacia de una intervención diseñada para favorecer unas actitudes más positivas hacia las personas con trastornos mentales entre los universitarios de Delhi. Un total de 50 jóvenes participaron en una intervención educativa y de contacto. Se evaluaron las actitudes hacia las personas con enfermedades mentales antes, justo después y una semana después de la intervención. Los resultados aumentaron los sentimientos de benevolencia, y la ideología de salud mental comunitaria y redujeron el autoritarismo en las evaluaciones después de la intervención. También se apreció una disminución del apoyo de la restricción social, pero solo en el caso de la evaluación inmediatamente posterior. Asimismo, se observó un mayor reconocimiento de las necesidades, más descripciones positivas, menos descripciones negativas y se redujeron las etiquetas después de la intervención. Estos resultados respaldan la eficacia de las estrategias de educación y contacto para reducir el estigma de los trastornos mentales. Se discuten las implicaciones de estos hallazgos para países de ingresos bajos-medios como la India.

Mental illness stigma can be comprehensively defined as the “devaluing, disgracing, and disfavouring by the general public of individuals with mental illnesses” (Abdullah & Brown, 2011). Stigma encompasses three inter-related constructs: stereotypes (for e.g., persons with mental illness are aggressive), prejudice (for e.g. I do not want to be friends with someone who has a mental illness) and discrimination (for e.g., refusing to give a job to a person with mental illness) (Corrigan, 2004). The cluster of negative beliefs, attitudes and resultant behaviours that surround mental health problems can be debilitating for people effected by them. Due to widespread misconceptions and stigmatization, families tend to conceal members with mental illnesses. Social exclusion takes other forms as well. For example people report being unwilling to spend an evening socializing, work next to, or have a family member marry a person with mental illness (Martin, Pescosolido, & Tuch, 2000). Lack of direct contact caused by different forms of social exclusion further perpetuates negative attitudes. Stigma can reduce access to health care (Desai, Rosenheck, Druss, & Perlin, 2002), inhibit persons at risk from using mental health services (Leaf, Bruce, Tischler, & Holzer, 1987) and decrease adherence to treatment regimes (Sirey et al., 2001). Research has suggested that many people choose not to pursue mental health services because they do not want to be deemed a “mental patient” or suffer the prejudice and discrimination the label brings (Ben-Zeev, Young, & Corrigan, 2010). Further, the internalization of negative views has been linked to low self-esteem, negative emotional states and self-blaming (Link, Cullen, Frank, & Wozniak, 1987).

Stigma can also lead to adverse economic effects for persons with mental illness by negatively impacting employment, income and public views about resource allocation and healthcare costs (Sharac, McCrone, Clement, & Thornicroft, 2010). Public funding for research on mental illnesses typically falls well below what is provided for other disabling conditions. Attitudes towards mental illness also create fund-raising challenges for voluntary organizations, making it extremely difficult for agencies to attract funds at the level seen for conditions like cancer and heart disease (Stuart, Arboleda-Florez, & Sartorios, 2012).

As in other parts of the world, mental illness stigma is highly prevalent in India. A cross sectional survey of Indian patients with psychiatric disorders indicated that 90% of the sample had experienced stigma and that stigma was perceived irrespective of age, mental status, rank and education (Pawar, Peters, & Rathod, 2014). Moreover stigma tends to be experienced in various domains. A study on patients with schizophrenia from an outpatient department of a psychiatric hospital in Mumbai revealed that stigma was perceived to be highest in the familial, social and personal contexts. Also prevalent were reports of being avoided due to their illness, discrimination suffered in the family, overhearing offensive comments about mental illness and discrimination at the work place. Close to half the respondents reported problems coping with their marriage and not receiving proposals for marriage due to their illness (Shrivastava et al., 2011). In a study on the experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in three diverse settings in India, Koschorke et al. (2014) found that more internalized forms of stigma such as a sense of alienation were even more common than experiences of negative discrimination.

Stigma originates from multiple and interacting sources including lack of education, lack of perception, and the nature and complications of the mental illnesses (Arboleda-Flórez, 2002). A strikingly large percentage of participants (97%) in Shrivastava et al.’s (2011) study believed that persons with schizophrenia are stigmatized due to lack of awareness. This lack of awareness is pervasive (Salve, Goswami, Sagar, Nongkynrih, & Sreenivas, 2013) and outmoded beliefs about mental conditions continue to prevail in the country leading to the stigmatization of patients and their families. Mental illness tends to be attributed to supernatural causes and the pathway to care is often shaped by doubts about mental health services and treatments options (Lauber & Rossler, 2007). In a study on myths, beliefs and perceptions about mental disorders and health-seeking behaviour in India, Kishore, Gupta, Jiloha, and Bantman (2011) found a large number of participants to believe that prayer could alleviate mental illness and that ghosts could be removed by a ‘tantrik’ or ‘ojha’. The attitude towards psychiatrists, particularly in participants from rural areas was negative. Cultural factors further influence people's beliefs and attitudes. In Asian cultures the emphasis on conformity to norms and emotional self-control leads mental illnesses to be seen as a source of shame (Abdullah & Brown, 2011). Mental illness may be explained as a manifestation of spiritual or moral transgressions and thus be regarded with a sense of guilt. For a nation such as India which grapples with multiple economic, social and political challenges, mental illness does not appear to be a high priority issue. In developing countries, national budgetary allocations for the treatment and management of mental conditions are minimal or none (Stuart et al., 2012). In India, mental health expenditures by the government health ministry are 0.06% of the total health budget (WHO, 2011). Fewer resources being allocated to the area inhibit efforts to alter the existing state of affairs.

Addressing stigma is essential to ensuring that persons with mental illness are able to lead lives of dignity and gain access to resources they need. Despite the prevalence of stigma in Indian samples and the implications it has for the lives of persons who have mental illness, the scarcity of anti-stigma programmes in the country is conspicuous. In comparison with campaigns conducted in affluent countries, the development of anti-stigma programmes is still insufficient in low and middle income countries (Mascayano, Armijo, & Yang, 2015). The present study attempted to address this gap. The objective of the study was to develop, implement and assess an intervention programme designed to foster more positive attitudes towards persons with mental illness among college students.

A review of past studies brought to the fore three types of strategies common among interventions that target mental illness stigma-contact, education and protest (Corrigan & Penn, 1999). Of these, the first two have been found to be successful (Pinfold et al., 2003; Reinke, Corrigan, Leonhard, Lundin, & Kubiak, 2004). Educational programmes have been directed at several kinds of audiences and tend to produce positive effects at least in the short-term (Corrigan & Penn, 1999; Essler, Arthur, & Stickley, 2006). Some benefits of educational interventions have been established specifically for undergraduate students (Boysen & Vogel, 2008; Masuda et al., 2007). Contact is likely to have an even greater impact on attitudes than education (Corrigan et al., 2001). However the intergroup contact hypothesis first proposed by Allport (1954) holds that positive effects of contact occur in situations characterized by four key conditions: equal status, common goals, intergroup cooperation and support by social and institutional authorities. Allport's formulations have received support from research conducted across a variety of situations and groups (e.g., Ellison and Powers, 1994; Smith, 1994). Research over the years has also illuminated other conditions that improve the outcomes of contact. For instance, studies within the field of mental illness have shown direct contact to be more beneficial than video-based contact (Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, & Rafacz, 2012). Given the well-established efficacy of both the strategies, we designed an intervention involving education as well as direct-contact to address negative attitudes towards persons with mental illness. We discuss the intervention in greater detail below.

MethodParticipants and procedureA total of 50 college students (27 females, 23 males) participated in the study. They ranged in age from 18 to 21 years and were recruited through convenience sampling from different colleges across the Delhi-National Capital Region. The participants were pursuing various academic courses such as History, English, Business and Journalism. However none had a background in psychology or psychiatry. The sample belonged predominantly to the upper-middle income category.

The intervention was conducted in a single two-hour session. On the day of the intervention, all the participants were seated together in a college auditorium. They were welcomed and asked to fill an informed consent form as well as a demographic sheet asking for basic information including their age, gender and course of study. The participants were then asked to complete two measures assessing their attitudes towards persons with mental illness.

Once this was done and the papers had been handed back to the researchers, the intervention was begun. The first part of the intervention involved a dance-drama which addressed the dominant myths that surround mental illness and provided corresponding facts. This dance drama was enacted by third year students majoring in psychology who had some theatre experience. The myths addressed included “Mental illness is caused by character flaws”, “Persons with mental illness are violent and dangerous” and “People with mental illness never get better.” We deliberately began with a creative medium like theatre to elicit the audience's interest. This was followed by the educational component in the form of a power point presentation delivered by the first author, who has over fifteen years of teaching experience. The presentation addressed the meaning of mental illness, relevant statistics, causes and treatments. We also provided information on famous persons with mental illness who have led or are leading successful lives. This included information on the acclaimed Bollywood actress Deepika Padukone who recently spoke about battling depression and has advocated a more pro-active approach to the treatment of mental illnesses. We felt it was necessary to provide such information given that a neurobiological understanding of mental illness, while embraced by the public does not translate into a decrease in stigma. Stigma reduction strategies need to emphasize competence and inclusion (Pescosolido et al., 2010). The last part of the intervention involved direct contact with a person who has successfully managed mental illness. The resource person we invited for this session is a young, vibrant artist and an advocate for the rights of persons with mental illnesses. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia in her early 20s and learnt to combat it successfully without using medication. This programme activity was particularly significant for the intervention and provided a rare opportunity for young people to directly engage with someone who had experienced mental illness.

Once the intervention was over, the participants were handed the measures again and requested to fill them. Then the papers were collected back and the session was concluded. A week after the intervention, researchers contacted the participants through email and had them fill out the tools for the third and last time.

The intervention can be conceptualized using Petty and Cacioppo's Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986a, 1986b) which states that there are two “routes” to persuasion: central and peripheral. The central route to persuasion consists of attention to arguments within a message. When a receiver engages in central processing, he or she is an active participant in the process of persuasion. We sought to tap the central route of persuasion through the educational and contact components of the intervention by providing accurate information on mental illness and the harm resulting from stigma. The peripheral route to persuasion occurs when the listener decides to agree with a message based on cues other than the strength of the arguments in it. We expected the dance-drama to be impactful by tapping both the central route (by challenging myths related to mental illness) and the peripheral route (through its novelty, visual appeal and innovative nature).

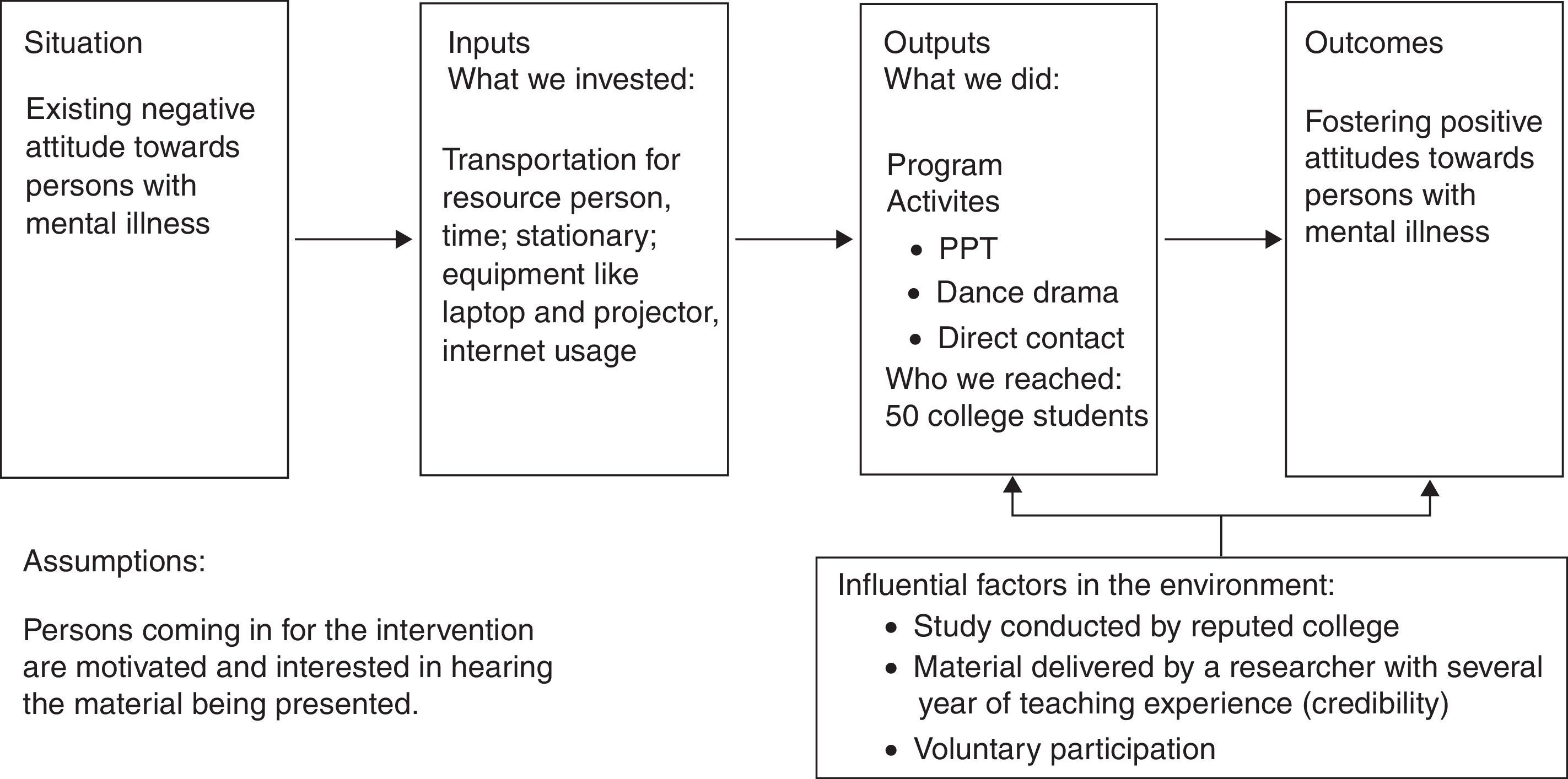

The activities and objectives of the present study can be tied together in a programme logic model as follows (Fig. 1).

ToolsOpen ended question: The participants were asked to respond to one open-ended question at the beginning of the pre and post assessment procedures. This question was: “What words or phrases come to your mind when you think of mental illness or a person with mental illness?” Three spaces were provided to the participant to respond. The purpose of this question was to understand the immediate notions or images participants associate with mental illness.

The Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness scale (CAMI): CAMI has been used extensively and in a variety of contexts assessing mental illness stigma (Taylor & Dear, 1981; Taylor, Dear, & Hall, 1979; Thornton & Wahl, 1996; Wahl, 1993). CAMI consists of 40 items and uses a 5-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. The measure is comprised of four subscales: authoritarianism, social restrictiveness, benevolence, and community mental health ideology. There are 10 items for each of these subscales, and 5 of these 10 are reverse-scored. Items for each subscale are summed together to provide one score ranging from 10 to 50. Because higher scores on one subscale indicate certain beliefs which are contradictory to higher scores on another factor, it is not meaningful to create a single composite score for the CAMI.

The reliability of the tool was assessed by the original authors of the CAMI (Taylor and Dear, 1981; Taylor et al., 1979), and the internal consistency of community mental health ideology was (α=0.88), benevolence was (α=0.76), social restrictiveness was (α=0.80), and authoritarianism was (α=0.68). Most of the subscales indicate moderate-high reliability and although authoritarianism was lower than the others, it is still considered satisfactory. To determine construct validity, Taylor and Dear (1981) performed factor analysis and examined the correlations among the factors. The lowest correlation was between authoritarianism and benevolence (r=−0.63) whereas the highest correlation was between social restrictiveness and community mental health ideology (r=−0.77). Two subscales are framed in an overall positive manner with respect to attitudes towards the mentally ill while the other two are more negative. Thus, it is not surprising that these correlations have a negative direction. Cotton (2004) further examined the correlations between the scales and found a moderately strong relationship between benevolence and community mental health ideology (r=0.389). The strongest correlation was between social restrictiveness and community mental health ideology (r=−0.771).

Data analysisThe Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS 16.0) was used to carry out the analysis of data collected. Means and standard deviations were obtained for all four subscales of the CAMI for each assessment (pre, immediate post and one week follow up). The three means obtained for each of the four sub scales were compared using ANOVA for dependent samples. Data from the open-ended question was analyzed using content analysis. In line with the quantitative tradition, the aim of the content analysis was the systematic organization of data into a set of categories that could represent the presence and frequency of specific ideas and allow a comparison of the three assessments. The results of this content analysis have been presented numerically. However some features of the qualitative tradition were also adopted. For example the process of identifying categories was inductive in that categories for describing the data evolved during the analysis. As the material was reviewed, tentative categories were generated. Then with the analysis of more material, categories were revised and a final set was determined. All four researchers were involved in the process of assigning responses to categories. Rather than having strict rules for maximizing objectivity in coding, space was allowed for extensive discussions and the approach of agreement between researchers were used to develop categories. As a rule of thumb, agreement among at least three out of four researchers was maintained as the standard for assigning a response to a category. Where there were differences of opinion, they were resolved through debate and discussion.

ResultsResults from CAMICorrelations between the sub-scales of CAMI were calculated. The strongest correlation was found between the sub-scales of social restrictiveness and benevolence (r=−0.77) followed by authoritarianism and community mental health ideology (r=−0.62). Unsurprisingly these correlations were negative. The weakest correlation was found between benevolence and community mental health ideology. However the relationship was positive in nature (r=0.46).

Further, to ascertain internal consistency of CAMI in the present study, Cronbach alpha was calculated. The values found for various sub-scales were community mental health ideology (α=0.84), benevolence (α=0.78), social restrictiveness (α=0.54), and authoritarianism (α=0.68).

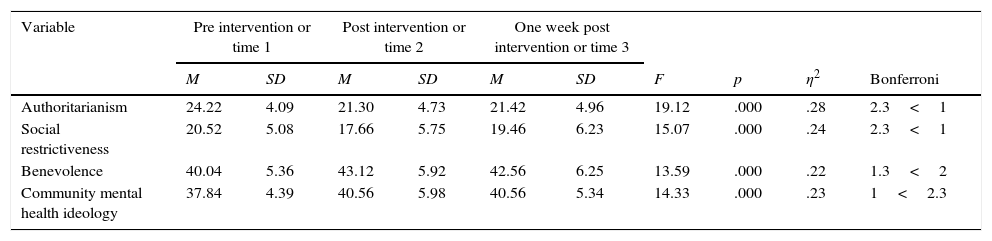

To assess if the intervention was effective, means obtained prior to the intervention were compared to means obtained immediately after it and one week later. Results for the Authoritarianism dimension on the CAMI indicated a decline in coercive attitudes towards mental health consumers after the intervention. ANOVA for dependent samples showed the differences in scores on the 3 occasions to be significant (F=19.12, p<.001, ηp2=.28). The post hoc test results showed the difference between pre and post-intervention and pre and post-one-week assessment to be significant. The difference between post and post-one-week assessment was not found to be significant (Table 1).

Means on authoritarianism, social restrictiveness, benevolence and community mental health ideology and post hoc results.

| Variable | Pre intervention or time 1 | Post intervention or time 2 | One week post intervention or time 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | η2 | Bonferroni | |

| Authoritarianism | 24.22 | 4.09 | 21.30 | 4.73 | 21.42 | 4.96 | 19.12 | .000 | .28 | 2.3<1 |

| Social restrictiveness | 20.52 | 5.08 | 17.66 | 5.75 | 19.46 | 6.23 | 15.07 | .000 | .24 | 2.3<1 |

| Benevolence | 40.04 | 5.36 | 43.12 | 5.92 | 42.56 | 6.25 | 13.59 | .000 | .22 | 1.3<2 |

| Community mental health ideology | 37.84 | 4.39 | 40.56 | 5.98 | 40.56 | 5.34 | 14.33 | .000 | .23 | 1<2.3 |

N=50.

Scores for the social restrictiveness subscale declined immediately after the intervention, but were found to increase at the one week follow-up. Although ANOVA for dependent samples showed the differences in scores on the 3 occasions to be significant (F=15.07, p<.001, ηp2=.24), post hoc test results showed the difference between pre and post-intervention and post and post-one-week assessment to be significant. The difference between pre and post-one-week assessment was not found to be significant.

Scores for the benevolence dimension increased after the intervention. ANOVA for dependent samples showed the differences in scores on the 3 occasions to be significant (F=13.59, p<.001, ηp2=.22). The post hoc test results showed the difference between pre and post-intervention assessment and pre and post-one-week assessment to be significant. The difference between post and post-one-week assessment was not found to be significant.

Scores for the Community Mental Health Ideology subscale increased after the intervention. ANOVA for dependent samples showed that the differences in scores on the 3 occasions was significant (F=14.33, p<.001, ηp2=.23). The post hoc test results showed the difference between pre and post-intervention and pre and post-one-week assessment to be significant. The difference between post and post-one-week assessment was not found to be significant.

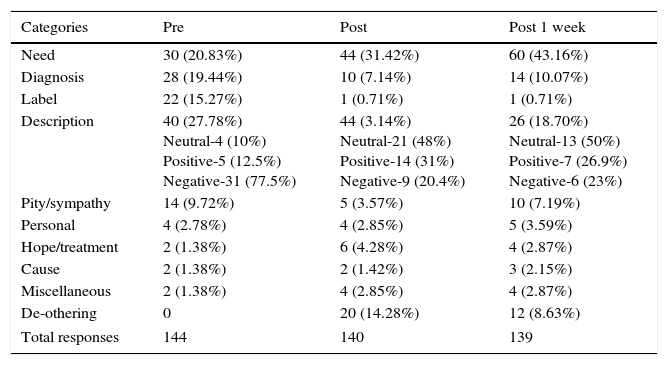

Results from the open-ended questionAs seen in Table 2, 20.83% of the responses elicited from participants during the pre-intervention assessment referred to the needs of persons with mental illness (for example ‘needs care’, ‘need help from psychologist’ and ‘should be given special treatment’). At the post-intervention assessment this increased to 31.42% and further increased to 43.16% at the time of the one week follow up.

Categories and frequencies emerging from the data of the open ended question.

| Categories | Pre | Post | Post 1 week |

|---|---|---|---|

| Need | 30 (20.83%) | 44 (31.42%) | 60 (43.16%) |

| Diagnosis | 28 (19.44%) | 10 (7.14%) | 14 (10.07%) |

| Label | 22 (15.27%) | 1 (0.71%) | 1 (0.71%) |

| Description | 40 (27.78%) Neutral-4 (10%) Positive-5 (12.5%) Negative-31 (77.5%) | 44 (3.14%) Neutral-21 (48%) Positive-14 (31%) Negative-9 (20.4%) | 26 (18.70%) Neutral-13 (50%) Positive-7 (26.9%) Negative-6 (23%) |

| Pity/sympathy | 14 (9.72%) | 5 (3.57%) | 10 (7.19%) |

| Personal | 4 (2.78%) | 4 (2.85%) | 5 (3.59%) |

| Hope/treatment | 2 (1.38%) | 6 (4.28%) | 4 (2.87%) |

| Cause | 2 (1.38%) | 2 (1.42%) | 3 (2.15%) |

| Miscellaneous | 2 (1.38%) | 4 (2.85%) | 4 (2.87%) |

| De-othering | 0 | 20 (14.28%) | 12 (8.63%) |

| Total responses | 144 | 140 | 139 |

The percentage of responses referring to different kinds of diagnoses of mental illness (for example ‘a psychotic stage’, ‘depression’ and ‘anorexia’) decreased from 19.44% at the pre-intervention assessment to 7.14% at the post-intervention assessment. They rose slightly (10.07%) at the one week follow up. Labelling (‘person is mad’, ‘crazy’ and ‘retard’) declined significantly from 15.27% at the pre-intervention assessment to 0.71% at both assessments done after the intervention. Positive descriptions (‘they are good people by heart’) increased from 12.5% to 31% at the post intervention assessment and dropped somewhat to 26.9% at the one week follow-up. On the other hand negative descriptions (‘stubborn’, ‘untidy and unclean’) decreased from 77.5% to 20.4% at the post-intervention assessment and increased somewhat to 26.9% at the one week follow-up. There were no instancing of de-othering (‘same as us’, ‘one amongst us’) found in the pre-intervention data. However 14.28% responses at the post-intervention assessment and 8.63% responses at the one week follow up were categorized as instances of de-othering.

DiscussionGiven the prevalence of stigma, it is encouraging to note that the present study found an increase in positive attitudes towards persons with mental illness after the intervention. Allport (1954) defines prejudice as “a preformed opinion, usually an unfavourable one based on insufficient knowledge, irrational feelings or inaccurate stereotypes”. Allport believed that prejudice is structured by social categorization or the ordering of the social environment in terms of social categories (Tajfel, 1974). This categorization can become the basis of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination. Tajfel and Turner (1979) in their social identity theory proposed that a person's need for positive self-identity may be satisfied by membership in prestigious social groups. This need motivates social comparisons that favourably differentiate in-group from out group members. People favour in-group members in the distribution of real rewards and penalties (Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament, 1971) and in assessing the products of their work (Ferguson & Kelley, 1964). Pro-social behaviour is offered more eagerly to in-group than to out-group members (Piliavin, Dovidio, Gaertner, & Clark, 1981). People are also more generous and forgiving in their explanations for the behaviours of in-group members. One reason may be that shared in-group membership diminishes psychological distance and facilitates the arousal of empathy (Homstein, 1976).

Given this literature, the present intervention attempted to encourage participants to revisit some of the categorizations they held about persons with mental illness through three mediums: a dance-drama, education and face-to-face contact.

An important strength of educational interventions is that they tend to be low cost and can be widely disseminated as is required presently in India. These interventions are understood to work because they directly replace incorrect information about mental illness with facts and appear grounded in Allport's idea that prejudice stems from insufficient knowledge and stereotypes. To make the educational component as effective as possible, we focussed on providing factual information in a way that was interesting, clear and simple to comprehend for college students who did not have a background in psychology. Informal interactions with participants after the intervention lead us to believe that even more impactful than the educational component was the strategy of direct contact. Given previous research (Corrigan et al., 2001) we had expected this. As mentioned earlier, Allport's ‘Contact hypothesis’ (1954) holds that contact between two groups can promote tolerance and acceptance but only if certain conditions like equal status, common goals, intergroup cooperation and support of authorities are met. Many of these conditions seem to have been met in the study: participants and the resource person were of equal status and similar backgrounds; there was no competition, the larger institution and its representatives supported the idea of more egalitarian attitudes and there was personal interaction between the resource person and the audience. The nature of the contact is often most helpful when the contact person is an individual of similar age to the participants and only ‘moderately’ disconfirming of stereotypes (Reinke et al., 2004). In the present case, this was apparent as the resource person presented a realistic view of her recovery where coping with schizophrenia involved much internal struggle, took time and required the acceptance of her loved ones and the support of her psychiatrist. Also, the resource person while older than the participants by almost ten years looked very young. She addressed the audience informally, shared her lived experiences candidly, engaged the participants in exercises that would help them feel what she had felt during an episode of schizophrenia and encouraged them to ask her questions. This seems to have enabled the participants to relate to her and empathise with her easily.

From Brewer and Miller's (1984) point of view, the features of contact reduce bias because they contribute to the process of de-categorization. De-categorization refers to treating persons as unique individuals rather than as members of larger groups (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000a). The de-categorization perspective proposes that if the members of two groups see themselves as distinct individuals (Wilder, 1981) or have personalized, self-disclosing interactions to enable them to get to know one another (Pettigrew, 1997, 1998), the validity of out-group stereotypes is undermined and inter-group bias is reduced (Brewer & Miller, 1984; Miller, Brewer, & Edwards, 1985). As people focus on information about an out-group member that is relevant to the self as an individual rather than self as a group member, they move away from employing category identity as the most useful basis for classifying each other (Brewer & Miller, 1984; Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000a). We identified several instances of de-categorisation in the data collected through the open-ended question. When asked to respond to the question during the pre-assessment phase, one participant described persons with mental illness as “disturbed” and “unstable”. Her response to the same question immediately after the assessment was “equal, honest, real”. It is quite likely that the interaction with the resource person enabled the participant to relate to her as an individual in her own right – as someone who was honest about who she is and thus ‘real’. Another process that may have operated through the intervention is re-categorization, which refers to a shift in boundaries between the in-group and out-group. In contrast to de-categorization, re-categorization refers not to the reduction or elimination of categorization but to creating a definition of group categorization at a higher level of category inclusiveness in ways that reduce intergroup bias (Allport, 1954, p. 43; see Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000b). During the pre-assessment intervention one participant had described persons with mental illness using the terms “restlessness, depression, unable to perform day-to-day activities.” Her responses immediately after the intervention changed to “same as us” and “creative.” At the one week follow-up her responses to the question were “should be given respect like any other individual” and “are unique in their own way.” Expressions such as ‘same as us’ and ‘like any other individual’ show a more inclusive attitude on part of the participant. The use of terms like ‘creative’ and ‘unique’ once again indicate the occurrence de-categorization. The resource person had been introduced to the participants as an artist known for her paintings and writing. It is very possible that ‘creative’ was used to refer to her. The fact that she openly talked about her illness and adopts an unconventional appearance (pink hair, piercings and tattoos) may have led the participant to appreciate her individuality.

According to Pettigrew (1998) de-categorization, re-categorization and mutual differentiation processes contribute to the reduction of intergroup bias and conflict. The mutual intergroup differentiation model (Hewstone & Brown, 1986) encourages groups to emphasize their mutual distinctiveness within a situation of cooperative interdependence. For instance, by dividing the labour required for a particular task in a complementary way, the members of both groups can come to appreciate the valuable contributions of the other (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000a). Mutual differentiation allows group members to maintain their group identities but prevents negative intergroup comparisons. In the present study, very few instances of mutual differentiation were identified in both sets of post-intervention data. In total, there were only two responses that could be categorized as such. It appears that while the intervention succeeded in encouraging participants to adopt less stereotypical and negative attitudes towards persons with mental illness, it did not facilitate them to believe that persons with mental illness can play complementary roles towards them. It must be said that the intervention was mainly geared towards providing accurate information, breaking myths and identifying what needs to be done to address the needs of persons with mental illness. Due to this emphasis, it is possible that the participants positioned themselves in terms of what they can do for persons with mental illness, rather than how persons with mental illness could play mutual and complementary roles towards them. Future interventions must highlight this aspect of complementarity.

Corrigan (2011) argues that mental illness stigma reduction is most likely to be effective when it is targeted towards specific populations, is locally based and delivered, continuous, credible and involves contact with people who have successfully managed mental illness. Of the points mentioned here, the present intervention covered all except continuity. In addition, participation was voluntary and the message was not delivered forcefully. Thus, there was little scope of reactance. Evidence of the success of the intervention is indicated by the fact that most positive outcomes found at the immediate post-assessment persisted at the one week follow-up. However there were some outcomes that did not last or were reversed to some degree. This was very apparent in the case of the social restrictiveness subscale of the CAMI, where scores at the one-week follow-up were similar to the scores at the pre-intervention assessment. A strengthening of the belief that persons with mental illness should be restricted may be related to the increasing awareness participants demonstrated of the needs of persons with mental illness across the two post-intervention assessments (Table 2). Such recognition of needs, on the one hand appears to be positive, because it signifies an appreciation of the importance of appropriate treatment, care and support. On the other hand believing that persons with mental illnesses have strong needs and positioning themselves as those who must fulfil the needs may have resulted in participants expressing greater social restrictiveness at the time of the one week follow-up. The participants may have felt that a group with a high number of needs requires supervision rather than being awarded responsibilities. Related to this point, expressions of pity increased and de-othering decreased somewhat in the one week follow up. While the results indicate that education and direct contact sessions are a useful approach for challenging negative attitudes, it is also apparent that such programmes should be conducted at regular intervals order to ensure long lasting effects.

The stigma around mental illness can thus be understood by extending the social identity theory. Just as our sense of who we are is based on our group memberships, especially the ones that are prestigious, similarly our identity and self worth may also come from our distancing ourselves from certain groups that horrify us. It is proposed that because we find it uncomfortable to deal with the mentally ill, we create a greater distance between them and us than what truly exists so that we do not have to feel threatened or worried about being one of them. We call this the social dis-identity hypothesis. Since the intervention reduced this psychological distance as was seen through the processes of de-categorization and re-categorization, it was deemed effective.

The study is however, not without limitations. The intervention was brief and only a one week follow-up was taken. Long term effects were not assessed. Also the sample for the study was small and not representative of college students. The study did not have a control group. We cannot claim definitively that the changes in the attitudes of the participants were due to the intervention. The data was collected through self-report measures. It is possible that some participants were less than forthright with their opinions. Most importantly, while the intervention was successful in reducing negative attitudes towards mentally ill people, we cannot be sure if this change will translate into more positive behaviours.

Further research must be carried out with samples from different settings and from different parts of the country. Interventions must be geared to the populace they are meant for. We tailored our intervention to college students belonging to urban pockets of the country. Very different approaches may be needed for other sub-groups of the Indian population. For example in working with rural populations more emphasis may have to be placed on explaining the role of mental health professionals and challenging beliefs about supernatural forces as causal agents in mental illnesses. Lack of information on the work of psychiatrists, psychologists and counsellors aggravates mental illness stigma in developing countries.

The present study used a combination of three different intervention strategies. In future researches, it could be fruitful to see which one specifically has been most effective. Future interventions can also explore alternative methods of contact such as those involving closer one to one interaction between participants and resource persons, for example working together on assigned tasks. Contact with the family or friends of persons with mental illness would provide a new perspective as well. Dance-drama proved to be an effective educational technique in the present study and its use needs to be explored further, particularly in smaller towns and rural Indian settings where it is a popular form of recreation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We would like to express our deep appreciation to all students in the Psychology Honours course, Batch of 2016, Lady Shri Ram College for Women for their immense support in shaping the study, collecting data and analyzing it.