Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is a hypersensitivity reaction whose target organ is the upper respiratory tract. It affects approximately 15% of the world population, and it is most common in developed countries.1

In a chronic state, mucosal altered by persistent inflammatory reactions is easily infected; so the frequency of allergic rhinitis associated with sinusitis increases to 40% - 80% in adult patients.2

To keep the allergic reaction from causing damage, the immune system produces inhibitory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, including TGF-β.

The TGF-β family includes more than 30 proteins, which regulate a wide variety of biological processes, such as inhibition of proliferation, induction of apoptosis or cellular differentiation,3 haematopoiesis, extracellular matrix production and bone formation and healing.4,5 This molecule regulates T and B cell proliferation, as well as macrophage maturation and activation.

TGF-β has specific cellular receptors6 and is produced many cells types. The main source of plasma TGF-β is the platelet, these cells can store this protein.7 TGF-β is a regulatory cytokine of the immune response that increases in active processes of inflammation, such as those involved in type I hypersensitivity.

Over expression of this cytokine may cause fibrosis in some diseases, such as asthma. Some authors have found high levels of plasma TGF-β in asthmatic patients8 moreover, after challenge with an allergen, the expression of TGF-β was found to be increased in bronchial lavage fluid.9

In addition to TGF-β, mast cells release other factors, including platelet activating factor (PAF) and interleukins (IL) 4 and 5. Thus, there is an increase in TGF-β at sites with allergic inflammation where it may inhibit proliferation, mast cell degranulation and IgE synthesis.9,10 Further, TGF-β stimulates endothelial and fibroblast cells to produce IL-5 and eotaxin. If cytokine production is sustained over a long period of time, there may be increased susceptibility to infections due to lymphocyte inhibition. This may occur in allergic individuals and can alter circulating and cellular concentrations of TGF-β and the cells that produce it e.g., platelets. IL-11 is a potent inducer of platelet formation and besides being released by other cells, such as fibroblasts, this cytokine is produced by platelets, and its expression is increased by TGF-β. In addition to promoting coagulation, platelets are associated with other fundamental functions, including bactericidal functions11 and immune responses.12 Depending on the type of stimulus involved; platelet may become activated by prothrombotic mediators or pro-inflammatory mediators. The type of stimulus in turn therefore dictates the ultimate function on this cell. Platelet responses to normal aggregator stimuli are thus different from platelet response to allergen. In this manner, platelets may modulate immune-inflammatory reactions, including early and late-phase allergic responses, such as anaphylaxis.12

Objective

Studying the behavior of TGF-β in a type I hyper-sensitivity reaction, either alone or associated with infection, and the capacity of platelets to respond to increasing demands for TGF-β, was to determine the number of circulating platelets and the concentration of plasma and intra-platelet TGF-β in patients with allergic rhinitis and allergic rhinitis plus sinusitis (rhino-sinusitis).

Methods

This study was assessed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital, in Mexico City and all subjects gave informed consent. Patients were admitted to the Allergy and Immunology Service at the General Hospital of México, with a clinical diagnosis of allergic rhinitis and sinusitis supported by laboratory and Rx studies. All individuals included in this work were female, with a mean age of 42 years. The study included two groups of patients, one with seasonal allergic rhinitis (nasal congestion, clear watery discharge, paroxysmal sneezing, nasal itching, positive skin prick test to allergens); n = 6 and the other with rhino-sinusitis (allergic rhinitis plus sinusitis [purulent nasal discharge, malaise, headache or localized pain and tenderness over the involved sinus, bacterial positive cultures]; n = 18), the samples were drawn before initial treatment. Patients with endocrinopathy, pregnant or under antibiotic, steroid therapy or desensitization immunotherapy were excluded from the study. Twelve clinically healthy women with the same median age (42 years) participated as controls.

Plasma: Ten milliliters (ml) of peripheral venous blood was obtained from healthy volunteers and patients, without applying a tourniquet to the arm, in Vacutainer Diatube H (Beckton Dickinson) tubes containing 109 mM sodium citrate, 15 mM teophiline, 3.7 mM adenosine, and 0.198 mM dipiridamol (CTAD). The samples were processed to obtain plasma.

Platelets: The blood was centrifuged at 190 x g for 10 min, and the upper layer [platelet-rich plasma (PRP)] was isolated. The lower layer, which also contained platelets, was resuspended in washing solution (15mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% glucose, 0.05% serum bovine albumin, 145mM NaCl, pH 6.5) at 37°C and centrifuged at 190 x g for 10 min; the upper layer was added to the PRP. The PRP was centrifuged again at 190 x g for 5 minutes to remove contaminating non-platelet cells, and the supernatant was centrifuged at 900 x g for 10 min to precipitate platelets. The platelets were washed twice with washing solution by recentrifugation and finally resuspended in stabilizing solution (135 mM NaCl, 4 mM glucose, 2 mM EDTA, 13 mM sodium acetate) at 37°C to prevent spontaneous aggregation. Platelets were counted. Cell-free plasma was collected in 0.5 mL samples and stored at -70°C until measurement.

Plasma TGF-β-1: TGF-β was measured with a specific immunoenzymatic assay in the solid phase (EASIA kit, Biosource Europe, S. A. Belgium), following the manufacturer's instructions, in plasma samples derived from CTAD blood.

Intra-platelet TGF-β-1: To quantify active TGF-β, the platelets were disrupted by means of three cycles of freezing and thawing, followed by three cycles of sonication. After were then centrifuged at 500 x g for 15 minutes to eliminate the remaining platelets. TGF-β was measured in the supernatant using the EASIA kit.

IL-11: IL-11 was measured in plasma using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (ELISA; Quantikine Human IL-11, R & D Systems, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was performed by non-parametric Mann Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance tests. Differences were considered significant when p values were <0.05. The Spearman correlation was used to evaluate associations between the studied parameters.

Results

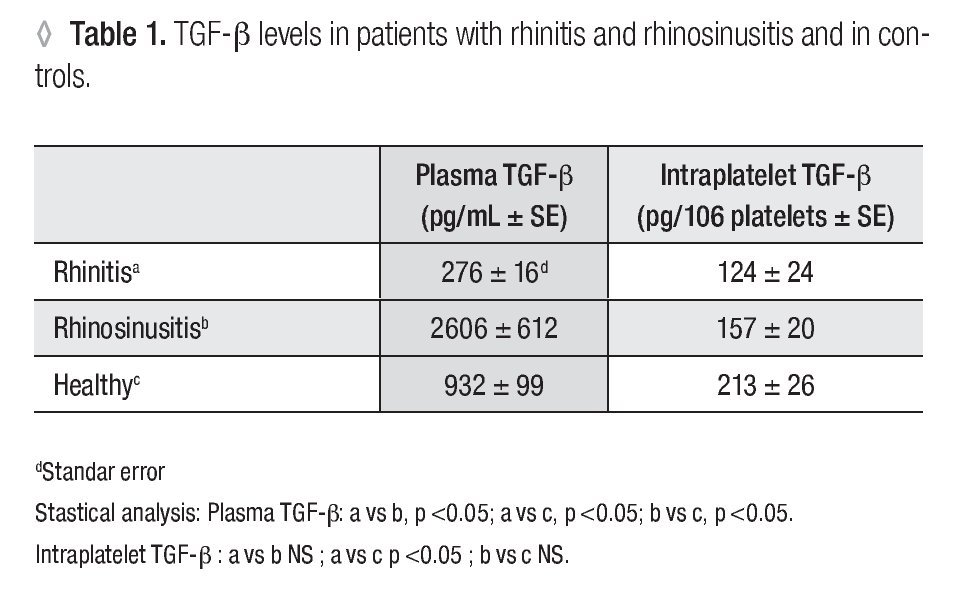

Plasma TGF-β-1: In patients with allergic rhinitis, the concentration (pg/mL ± SE) of TGF-β-1 (276 ± 16.1) was significantly smaller (p <0.005) than in the control group (932 ± 99.5). In the rhino-sinusitis group, the cytokine concentration (2606 ± 612.2) was greater (p <0.05) than in healthy individuals (Table 1).

Platelet Number: The number of platelets obtained (106 /ml ± SE) were 129 ± 18.6 for allergic rhinitis, 158 ± 14.3 for rhino-sinusitis, and 93 ± 11.1 for controls. The number of platelets in patients with rhino-sinusitis was significantly greater than in healthy individuals (p <0.05).

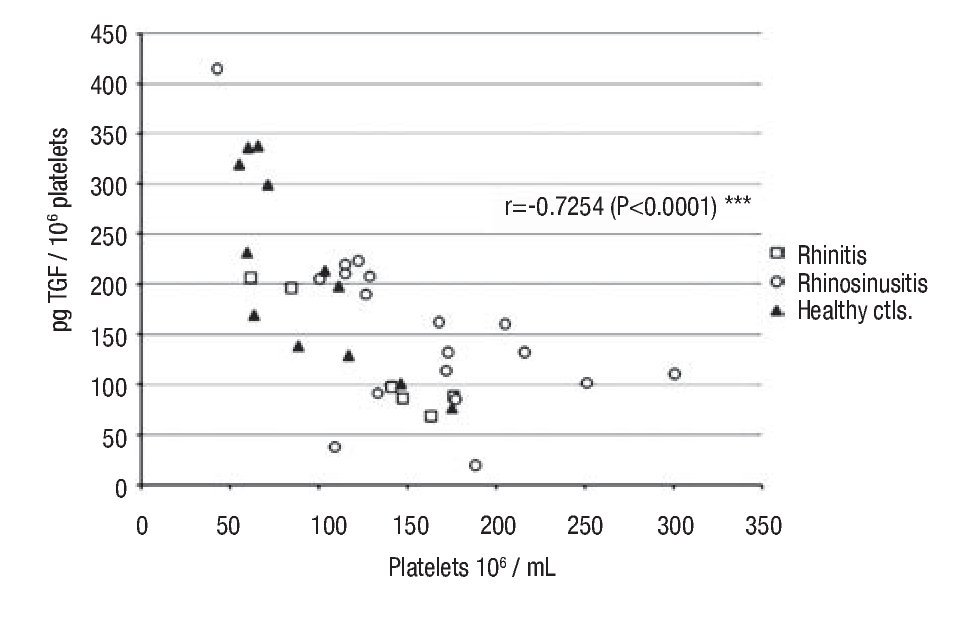

Intraplatelet TGF-β-1: In patients with rhino-sinusitis, the TGF-β concentration (pg/106 platelets ± SE) was lower (157 ± 20.9) than in normal subjects, but the difference was not significant. In patients with allergic rhinitis, the value (124 ± 24.7) was significantly less (p <0.05) than in healthy individuals (213 ± 26.8) (Table 1). There was a significant negative correlation (α = 0.05) between platelet number and the intraplatelet TGF-β-1 concentration (p <0.0001) (Figure 1) in the three studied groups.

◊ Figure 1. Negative correlation between intra-platelets TGF-β and circulating platelets number in the groups: a) rhinitis, b) rhino-sinusitis, c) controls.

Plasma IL-11: In patients with allergic rhinitis, the IL-11 concentration (pg/ml ± SE) was 2.3 ± 0.5 this value was not significantly different from those obtained in the rhino-sinusitis (2.8 ± 0.2) or control groups (1.9 ± 0.3). There was no correlation between the amount of circulating IL-11 and platelet number in any of the studied groups.

Discussion

TGF-β is a cytokine that exerts dual actions on several mechanisms, including cellular regulation, cancer and inflammation. In inflammation, TGF-β is pro-inflammatory in the early stages of the process and anti-inflammatory in the later steps. TGF-β is the most powerful physiological immunosuppressor, with strong anti-inflammatory tissue regenerative and healing properties.13 The final signaling outcomes depend on which partner proteins interact with the Smad complex in the nucleus and whether these are transcriptional, costimulatory or co-inhibitory factors.14 The available partner proteins are specific, depending on cell type and particular conditions.

In patients with allergic rhinitis, a decrease was observed in plasma and intra-platelet TGF-β levels, and the number of platelets was greater than in healthy individuals. However, some authors15,16 have reported a reduction in these cells during anaphylactic shock in mice.

The decrease in plasma TGF-β in patients with allergic rhinitis, suggests that the requirements for this cytokine at the affected site were increased by type I hypersensitivity processes. This promotes circulating cytokines coming into the damaged tissues. Regarding local cellular production, some authors observed significantly greater epithelial immunoreactivities to TGFβ-1, 2 and 3 receptors in patients with allergic rhinitis.17,18 High local demand may reduce TGF-β recirculation, moreover TGF-β can binds to some intercellular proteins (e.g., decorin) leading to sequestration19,20 and decreased availability in tissues during the allergic response. This could also further enhance the cytokine requirements.

In allergic processes, TGF-β inhibits the release of inflammatory mediators from mast cells and their exaggerated proliferation.21 Nevertheless, if increased TGF-β levels are maintained, they may induce fibrosis22 and an influx of eosinophils (cells that modulate the allergic reaction but can become aggressive) into the affected site.23 Among other factors and cytokines, eosinophils release TGF-β and some harmful proteins,8,24 which contribute to tissue damage and fibrosis. Finally TGF-β induces eosinophil apoptosis.25,26 Thus, injury to the tissue and inhibition of lymphocyte function (T, natural killer) by TGF-β would favor the establishment of infection, further complicating the condition.27 In patients with rhino-sinusitis in our study, plasma TGF-β and the number of circulating platelets were significantly higher than in healthy controls. However, intra-platelet cytokine levels were lower. Regarding increased plasma TGF-β levels, rapid production of TGF-β occurs following an infection. Cells participating in this process activate and produce others cytokines besides TGF-β, which recruit and active monocytes at the beginning of the inflammation process. The function of monocytes quickly changes due to the suppressor functions of TGF-β. Circulating monocytes exposed to bacterial components generate cytokines and factors that activate platelets to phagocyte and deliver antibacterial factors besides to free-radical oxygen species and cytokines (TGF-β). In addition to monocytes and neutrophils recruitment to the infection site, diapedesis and activation of platelets7,28 occurs; all of these activated components then participate in the antibacterial immune function. Many cells in circulation and in tissues are stimulated through Toll-like receptors,29 which can be activated by LPS and release a considerable amount of inflammatory and antibacterial substances and cytokines.

In this study, IL-11 concentration was greater in patients than in healthy individuals; however, the difference was not significant, and there was no correlation between plasma concentrations of IL-11 and the number of circulating platelets. It could be explained by the presence of the other factors like thrombopoietin, IL-13, IL-6 that besides to IL-11 promote platelet number too. These cells participate in hypersensitivity processes and contain high and low-affinity IgE receptors. IgE stimulation of platelets represents a non-thrombotic pathway by which they can be specifically activated by allergen and thus directly contribute to inflammatory responses observed in allergy.11,30 Platelet recruitment and degranulation into the lungs following antigen challenge in sensitized mice occurs before histamine release from mast cells, and therefore platelets may participate in anaphylaxis directly in response to IgE.31 Some authors have observed an absence of anaphylaxis in animals deprived of these cells.32

Analyzing platelet numbers and TGF-β intra-platelet concentrations, we observed an inverse and significant correlation in healthy individuals and in allergic patients, with or without infection. This suggests the involvement of a regulatory mechanism different from those previously described where platelets maintain a constant generation of TGF-β. To support this homeostasis, platelet probably adjusts the intracellular cytokine concentration to compensate for changes in the number of circulating platelets.

Our results suggest the possible involvement of other platelet mechanisms that are not well-established. Thus, we must continue to increase our understanding of participating platelet processes or pathways that could impact the regulation of the immune response.

It is necessary to perform further studies on cytokine functions that participate in the regulation of inflammation and fibrosis production.

Correspondencia: Gloria Bertha Vega Robledo.

Torre de Investigación 5° piso, Facultad de Medicina UNAM. Av. Universidad 3000 circuito escolar s/n, Col.

Copilco, CP 04510, México, D. F. México. Telephone and Fax: +5255 5623 2332.

E-mail: gloriavr@liceaga.facmed.unam