To identify the health-related physical fitness profile of Brazilian adolescents (10–17 years) living in a small town of German colonization and to describe the prevalence of those with low levels of physical fitness according to sex and age.

MethodThis is a school-based cross-sectional epidemiological study conducted with all adolescents (10–17 years) enrolled in five public schools of São Bonifácio, Brazil. The study included 277 adolescents (145 boys and 132 girls). The FITNESSGRAM® test battery was applied for the assessment of percent body fat, flexibility, muscle strength/endurance and cardiorespiratory fitness.

ResultsHigher mean values of percent body fat and flexibility (p<0.01) were found in girls; boys showed higher means (p<0.01) for pull-up and cardiorespiratory fitness tests. The prevalence of adolescents with low levels of physical fitness was high for percent body fat (boys: 29.3%, girls: 31.8%, p=0.75), flexibility (boys: 26.9%, girls: 54.5%, p<0.01), muscle strength/endurance (curl-up: 37.9% of boys and 45.5% of girls, p=0.25; modified pull-up: 47.6% of boys and 54.5% of girls, p=0.30) and cardiorespiratory fitness (boys: 28.0%, girls: 36.9%, p=0.15). As for the overall physical fitness, 75.7% of boys and 88.9% of girls did not meet the minimum recommended values (p=0.01).

ConclusionEffective intervention programs are necessary to promote changes in the health-related physical fitness profile of adolescents from São Bonifácio, Brazil.

Identificar el perfil de aptitud física y salud de adolescentes brasileños (10 a 17 años) de una pequeña ciudad de colonización germánica, así como describir la prevalencia de aquellos con baja aptitud física de acuerdo al sexo y la edad.

MétodoEstudio epidemiológico transversal de base escolar realizado con todos los adolescentes (10 a 17 años) de cinco escuelas públicas de San Bonifacio, SC (n=277; 145 niños), en 2010. Se utilizó la batería de tests FITNESSGRAM® para evaluar la porcentaje de grasa corporal, la flexibilidad, la fuerza/resistencia muscular y la aptitud cardiorrespiratoria.

ResultadosSe encontró un mayor porcentaje medio de grasa corporal y de flexibilidad (p<0.01) en las niñas; en los niños se obtuvieron mayores porcentajes medios en dominadas y en los test de aptitud cardiorrespiratoria (p<0.01). La prevalencia de adolescentes con baja aptitud física fue elevada para la grasa corporal (niños: 29.3%; niñas: 31.8%; p=0.75), para la flexibilidad (niños: 26.9%; niñas: 54.5%; p<0.01), para la fuerza/resistencia muscular (test de abdominales: 37.9% de los niños y 45.5% de las niñas, p=0.30) y para la aptitud física cardiorrespiratoria (niños: 28.0%; niñas: 36.9%; p=0.15). En cuanto a la aptitud física general, 75.7% de los niños y 88.9% de las niñas no alcanzaron los valores mínimos recomendados (p=0.01).

ConclusiónSon necesarios programas efectivos de intervención para la promoción de cambios en el perfil de aptitud física relacionada con la salud de adolescentes de San Bonifacio, SC.

Identificar o perfil da aptidão física relacionada à saúde de adolescentes brasileiros (10-17 anos), de origem étnica germânica e descrever a prevalência daqueles com baixa aptidão física, de acordo com o sexo e idade.

MétodoEstudo epidemiológico transversal de base escolar realizado com todos os adolescentes (10-17 anos) de 5 escolas públicas de São Bonifácio (Brasil). O estudo incluiu 277 adolescentes (145 rapazes e 132 moças). Aplicou-se a bateria de testes FITNESSGRAM® para avaliar o percentual de gordura corporal, flexibilidade, força/resistência muscular e aptidão cardiorrespiratória.

ResultadosAs moças apresentaram maiores valores médios de percentual de gordura e de flexibilidade (p<0.01). Os rapazes apresentaram melhor desempenho nos testes de flexão de braços e aptidão cardiorrespiratória (p<0.01). A prevalência dos adolescentes que não atingiram a zona saudável de aptidão física foi elevada para a gordura corporal (rapazes: 29.3%; moças: 31.8%; p=0.75) flexibilidade (rapazes: 26.9%; moças: 54.5%; p<0.01), força/resistência muscular (teste abdominais: 37.9% dos rapazes e 45.5% das moças, p=0.25; teste de flexão de braços: 47.6% dos rapazes e 54.5% das moças; p=0.30) e aptidão cardiorrespiratória (rapazes: 28.0%; moças: 36.9%; p=0.15). Na aptidão física geral, 75.7% dos rapazes e 88.5% das moças não atingiram o mínimo proposto para a saúde (p=0.01).

ConclusãoProgramas efetivos de intervenção são necessários para a promoção de mudanças no perfil da aptidão física relacionada à saúde dos adolescentes de São Bonifácio (Brasil).

Physical fitness is an important health marker since childhood and adolescence,1 and the maintenance of satisfactory levels is related to the reduction in the incidence of risk factors for chronic degenerative diseases such as obesity, diabetes mellitus type 2, systemic arterial hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases in adulthood.2

In Europe, low levels of physical fitness are observed in adolescents of both sexes.3,4 The prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness is 31.6% in teenage boys and 42.4% in teenage girls (12.5–17.5 years).3 As for body composition, body overweight is present in 25.9% and 19.2% of male and female adolescents (13.0–18.5 years), respectively.4 In medium and large size cities in Southern Brazil, it has been observed an increase in inadequate levels of adolescents’ body composition,5 cardiorespiratory fitness,6 muscle strength/endurance5 and flexibility7 for the health.

The components of physical fitness differ between ethnic groups8,9 and are influenced by phenotype.10 Although adolescents from large urban centers are exposed to low physical fitness, the access to the available physical spaces, such as parks, squares and clubs, are considered appropriate for physical activity11 and thus for the maintenance of physical fitness levels in these cities. However, in small town investigated, the access to these spaces is limited, due to lower availability.

Even though the Brazilian literature has reports on health-related physical fitness in adolescents,5–8 most studies were conducted in large urban centers.5–7 However, it is not totally clear yet whether the physical fitness profile of adolescents from small municipalities colonized by Europeans differs from that observed in studies carried out in large urban centers from Southern Brazil and in municipalities from other Brazilian regions and from Europe, for this reason, this study is justified.

Considering that external influencing factors of physical fitness are similar among adolescents, it will be possible to observe whether body composition and motor performance differ from those observed in studies conducted with heterogeneous populations and whether the proportion of adolescents who does not meet the health criteria for physical fitness is the same as that found in adolescents from larger urban centers. Furthermore, studies using the new cutoff points12,13 proposed by FITNESSGRAM® have not been carried out in Brazil yet.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to identify the health-related physical profile of Brazilian adolescents, from 10 to 17 years of age, living in a small town of German colonization and to describe the prevalence of those who do not meet the criteria for health-related physical fitness according to sex and age.

MethodStudy design and participantsThe study on health-related physical fitness analysis in adolescents was developed from a epidemiological cross-sectional project called “Physical activity and lifestyle: a three-generation study in São Bonifácio, Santa Catarina” (“Atividade física e estilo de vida: um estudo de três gerações em São Bonifácio, Santa Catarina”), approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), process no. 973/2010. This study has been conducted so far with all adolescents (10–17 years) from São Bonifácio, Brazil. This town from the state of Santa Catarina was intentionally selected, according to the following criteria: being small and colonized by the Germans.

The southern region of Brazil was predominantly colonized by Europeans. The first European colony settled in Santa Catarina was German, considered the second largest ethnic group in the region, after the Italians. This state has received immigrants from various countries of Europe, and Germans settled in northern and southern state of Santa Catarina, and São Bonifácio stands out for being colonized only by Germans.14

São Bonifácio is located 70km far from Florianópolis, state of Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil. Its population is of 3008 inhabitants, 77.23% of which live in the rural area. The colonization of the town began in 1864, when the first German immigrants arrived, coming from the region of Westphalia. Its economy is based on agriculture, with emphasis on tobacco plantation, olericulture, and dairy manufacturing.15 The town has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.785, being classified into medium HDI.16

The target population of the study were adolescents aged 10–17 years enrolled in public schools of São Bonifácio, SC, Brazil in 2010 (N=291). According to the World Health Organization,17 individuals aged 10–19 years are considered adolescents. São Bonifácio has one state and four municipal schools. A school census was conducted and all adolescents at the age group to participate in the study were invited. All adolescents aged 10–17 years were eligible for this study (n=277) and agreed to participate by presenting the consent form signed by their parents or guardians, who were present at school on the day of assessment and able to perform the physical tests.

Data collectionThe team of evaluators comprised 14 physical education professors and students from Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. The Physical Education students were assistants in data collection. The measures and tests were applied by teachers. A previous training was performed for standardization and application of physical tests and anthropometric evaluation. Each evaluator was responsible for the same test from beginning to end of measurements.

The period of data collection was seven days, in September 2010, in the school premises, during class time. Firstly, in a previously prepared room, anthropometric measures (body mass, height, and skinfold thickness) were obtained. Next, adolescents were taken to a multi-use gymnasium, were they performed the physical tests in the following order: back saver sit and reach, curl-up, modified pull-up, and 20-m shuttle run test. No warm-up was performed before the execution of the physical fitness tests.

Anthropometric variablesBody mass was measured with a digital weight scale (Filizola®), with a 150kg capacity and 100g scale. Height was obtained with a stadiometer (Sanny®), measuring scale of 0.1cm. Triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses (TSF and SSF respectively) were collected using the Cescorf® scientific skinfold caliper, a Brazilian model with design and mechanics similar to those of the English Harpenden® skinfold caliper, with a constant pressure of around 10g/mm2 for any opening of its jaws, measuring unit of 0.1mm, and contact area (surface) of 90 mm2. The measurements were performed by two trained evaluators and followed FITNESSGRAM® standards.18 To perform this task, they had their intra- and inter-evaluator Technical Error of Measurement (TEM) calculated before data collection with a sample of 17 adolescents, using the difference method, according to the procedures described by Gore et al.19 The limit for intra-evaluator TEM was 3% for skinfold thicknesses and 1% for other measures. For inter-evaluator TEM, the error limit was considered as 7% for skinfold thicknesses and 1% for other measures. To assess body composition, TSF and SSF were employed in the calculation of percent body fat, using the equation of Slaughter et al.20

Physical fitnessThe components of health-related physical fitness investigated were: body composition, flexibility, muscle strength/endurance, and cardiorespiratory fitness. The measurement of these components followed the procedures proposed by FITNESSGRAM®.18 The tests applied were: back saver sit and reach, curl-up, pull-up modified and 20-m shuttle run. Due to the high correlation between flexibility of right and left legs (r=0.92), the mean for the two measures was used. Data from the test were processed using the following equation, which was proposed by Leger et al.,21 to estimate maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max): Y=31.025+(3.238*X1)−(3.248*X2)+(0.1536*(X1*X2)), in which Y: predicted value of VO2max in ml/kg/min; X1: running speed corresponding to the stage in km/h; X2: subjects’ age.

The cutoff values adopted to verify the proportion of adolescents who were not in the healthy fitness zone, specific for sex and age, were those described in FITNESSGRAM®,22Revision 8.6 and 9.x (2010) (Table 1). These adolescents were classified into the needs improvement zone, it means, they were evaluated as having low physical fitness. For overall physical fitness, adolescents were considered with low physical fitness if they were simultaneously in the needs improvement zone in all measured tests (percent body fat and back saver sit and reach, curl-up, modified pull-up and 20-m shuttle run [VO2max] tests).

Cutoff points for the healthy fitness zone.

| Age (years) | Body fat (%) | Flexibility (cm) | Muscle strength/endurance (curl-ups/repetitions) | Muscle strength/endurance (pull-ups/repetitions) | Cardiorespiratory fitness (ml/kg/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | |||||

| 10 | 8.9–22.4 | 20 | ≥12 | ≥5 | ≥40.2 |

| 11 | 8.8–23.6 | 20 | ≥15 | ≥6 | ≥40.2 |

| 12 | 8.4–23.6 | 20 | ≥18 | ≥7 | ≥40.3 |

| 13 | 7.8–22.8 | 20 | ≥21 | ≥8 | ≥41.1 |

| 14 | 7.1–21.3 | 20 | ≥24 | ≥9 | ≥42.5 |

| 15 | 6.6–20.1 | 20 | ≥24 | ≥10 | ≥43.6 |

| 16 | 6.5–20.1 | 20 | ≥24 | ≥12 | ≥44.1 |

| 17 | 6.7–20.9 | 20 | ≥24 | ≥14 | ≥44.2 |

| Girls | |||||

| 10 | 11.6–24.3 | 23 | ≥12 | ≥4 | ≥40.2 |

| 11 | 12.2–25.7 | 25.5 | ≥15 | ≥4 | ≥40.2 |

| 12 | 12.7–26.7 | 25.5 | ≥18 | ≥4 | ≥40.1 |

| 13 | 13.4–27.7 | 25.5 | ≥18 | ≥4 | ≥39.7 |

| 14 | 14.0–28.5 | 25.5 | ≥18 | ≥4 | ≥39.4 |

| 15 | 14.6–29.1 | 30.5 | ≥18 | ≥4 | ≥39.1 |

| 16 | 15.3–29.7 | 30.5 | ≥18 | ≥4 | ≥38.9 |

| 17 | 15.9–30.4 | 30.5 | ≥18 | ≥4 | ≥38.8 |

Descriptive analysis of the variables used means, standard deviations, medians, and frequency distributions. Data normality was analyzed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normal distribution was found for body mass and flexibility. Log10 transformation of the data was applied for the other variables, and normality was observed for SSF and percent body fat.

For the comparison of mean values between sexes, Student t test and the equivalent Mann–Whitney non parametric U test was used. Analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) was employed considering age and sex, together with the Bonferroni post hoc test, to locate the ages in which differences occurred within each sex, using the SISVAR program, version 5.1. The Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. Relative frequency was used to verify the percentage of adolescents with low physical fitness. The comparisons between two proportions were performed with Statistics for Biomedical Research (MedCalc) software, version 9.1.1, to identify the differences between sexes in each age group for each component analyzed. The confidence level adopted for the analyses was 95%. Data were digitized in Excel® software and analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 15.0.

ResultsAdolescents who did not had the free and informed consent signed by their guardians (n=3), were not present on the evaluation day (n=5), or refused to participate in the study (n=5) were excluded from the sample, as well as those who had a motor limitation that made it impossible to perform the physical tests on the evaluation day (n=1). Thus, the sample was composed by 277 adolescents (145 boys and 132 girls), with response rate of 90.5%. The relative frequency and absolute of the sample according to age for boys and girls, respectively: 10 years, 17.2% (n=25) and 9.1% (n=12); 11 years, 18.6% (n=27) and 18.2% (n=24); 12 years, 12.4% (n=18) and 15.9% (n=21); 13 years, 10.3% (n=15) and 14.4% (n=19); 14 years, 11.0 (n=16) and 9.8% (n=13); 15 years, 11.0% (n=16) and 15.9% (n=21); 16 years, 11.0% (n=16) and 7.6% (n=10); 17 years, 8.3% (n=12) and 9.1% (n=12). Compared to boys, girls showed higher means for TSF, SSF, percent fat, and flexibility (p<0.01). Boys showed higher means (p<0.01) for pull-up and cardiorespiratory fitness tests (Table 2).

General characterization of the sample. São Bonifácio, Brazil, 2010.

| Variables | Boys | Girls | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | x¯ | SD | Md | n | x¯ | SD | Md | ||

| Chronologic age (years) | 145 | 12.97 | 2.31 | 13.00 | 132 | 13.21 | 2.14 | 13.00 | 0.39 |

| Body mass (kg)* | 145 | 53.73 | 16.38 | 54.00 | 132 | 54.39 | 14.70 | 54.85 | 0.73 |

| Height (cm) | 145 | 159.45 | 16.38 | 160.50 | 132 | 159.94 | 10.31 | 162.85 | 0.75 |

| TSF (mm)* | 145 | 13.43 | 6.87 | 11.35 | 132 | 18.41 | 6.78 | 17.35 | <0.01 |

| SSF (mm) | 145 | 11.19 | 7.97 | 8.05 | 132 | 14.14 | 8.95 | 11.50 | <0.01 |

| Body fat (%)* | 142 | 20.13 | 11.36 | 16.82 | 132 | 26.62 | 8.83 | 25.17 | <0.01 |

| Flexibility (cm)* | 145 | 22.90 | 6.27 | 22.50 | 132 | 26.05 | 5.33 | 26.50 | <0.01 |

| Curl-ups (repetitions) | 145 | 26.90 | 21.29 | 21.50 | 132 | 23.55 | 19.18 | 19.50 | 0.23 |

| Pull-ups (repetitions) | 145 | 8.41 | 5.73 | 7.00 | 132 | 3.31 | 2.75 | 3.00 | <0.01 |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max) | 143 | 44.26 | 4.56 | 44.55 | 130 | 40.58 | 5.12 | 41.15 | <0.01 |

x¯: mean; SD: standard deviation; Md: median; TSF: triceps skinfold thickness; SSF: subscapular skinfold thickness; p-value for the Student t test* for body mass, TSF, percent body fat and flexibility. For the other variables, the Mann–Whitney U test (chronologic age, height, SSF, curl-up, pull-ups, and cardiorespiratory fitness) was used.

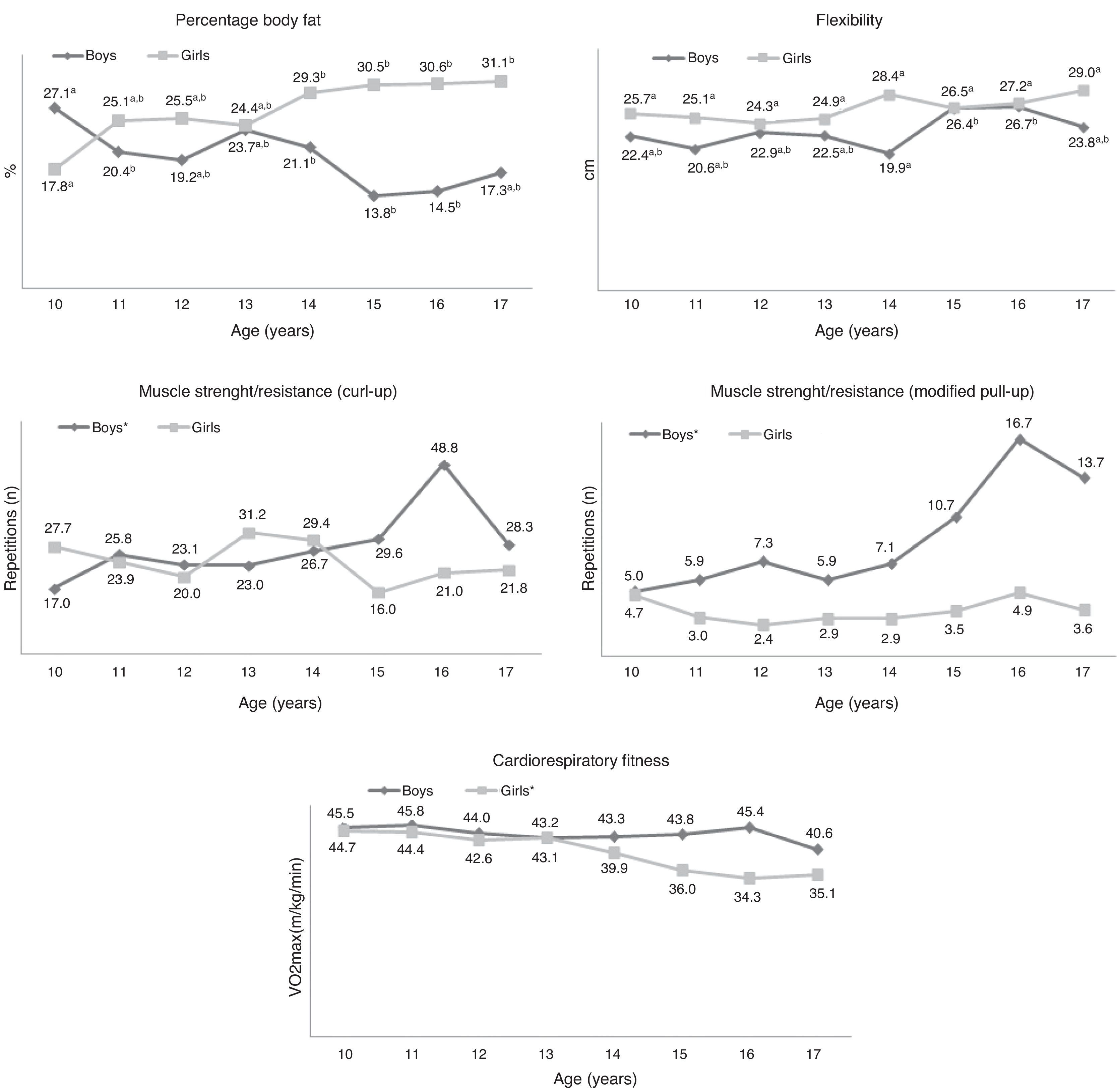

The differences in mean values of percent body fat between ages (F=7.38; p<0.01) were found in boys at age 10 years in relation to 11 (p<0.05), 14 (p<0.05), 15 (p<0.05) and 16 years, and at age 15 years compared with all ages (p<0.05). A higher percent body fat was observed at age 10 years and a lower percent at 15 years of age. In girls, the differences were found at age 10 years in relation to 14 and 17 years (p<0.05), with older girls showing higher mean values (Fig. 1).

Mean values of health-related physical fitness components in adolescents according to sex and age. São Bonifácio, Brazil, 2010. Same letters do not differ statistically between ages within the same sex (p>0.05) and different letters differ statistically between ages within the same sex (p<0.05). *p<0.05: differences between ages within the same sex for the Kruskal–Wallis test. Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests for percent body fat and flexibility. Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney tests for curl-ups, pull-ups and shuttle run.

Regarding flexibility, differences between ages were found only in boys (F=2.92; p<0.01). The lowest rate obtained was at 14 years, differing from ages 15 (p<0.05) and 16 years (p<0.05). In girls, flexibility remained constant throughout adolescence (F=1.57; p=0.15) (Fig. 1).

As for muscle strength/endurance, differences between ages became evident in boys for curl-up (p<0.01) and pull-up (p<0.01) tests. The performance was similar between ages among girls in both tests (p>0.05) (Fig. 1).

Physical fitness differed between ages in girls (p=0.02). The visual observation of the graph indicates lower mean values for older girls. In boys, physical fitness did not show significant differences between ages (p>0.05) (Fig. 1).

Concerning overall physical fitness classification, the prevalence of adolescents with low physical fitness was 75.7% for boys and 88.9% for girls, with differences between sexes (p=0.01). When the prevalence of the components was analyzed separately, the differences between girls and boys occurred only in flexibility (p<0.01). The proportion of adolescents with low physical fitness in the remaining components was similar between the sexes (p>0.05) (Table 3).

Prevalence of adolescents with overall low physical fitness and for each component, according to sex. São Bonifácio, Brazil, 2010.

| Components | Boys (%) | Girls (%) | χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall HRPF | 75.7 | 88.9 | 7.6 | 0.01 |

| Body fat | 29.3 | 31.8 | 0.2 | 0.75 |

| Flexibility | 26.9 | 54.5 | 20.8 | <0.01 |

| Muscle strength/endurance (curl-ups) | 37.9 | 45.5 | 1.3 | 0.25 |

| Muscle strength/endurance (pull-ups) | 47.6 | 54.5 | 1.1 | 0.30 |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max) | 28.0 | 36.9 | 2.1 | 0.15 |

HRPF: health-related physical fitness. p-Value for the test of two proportions.

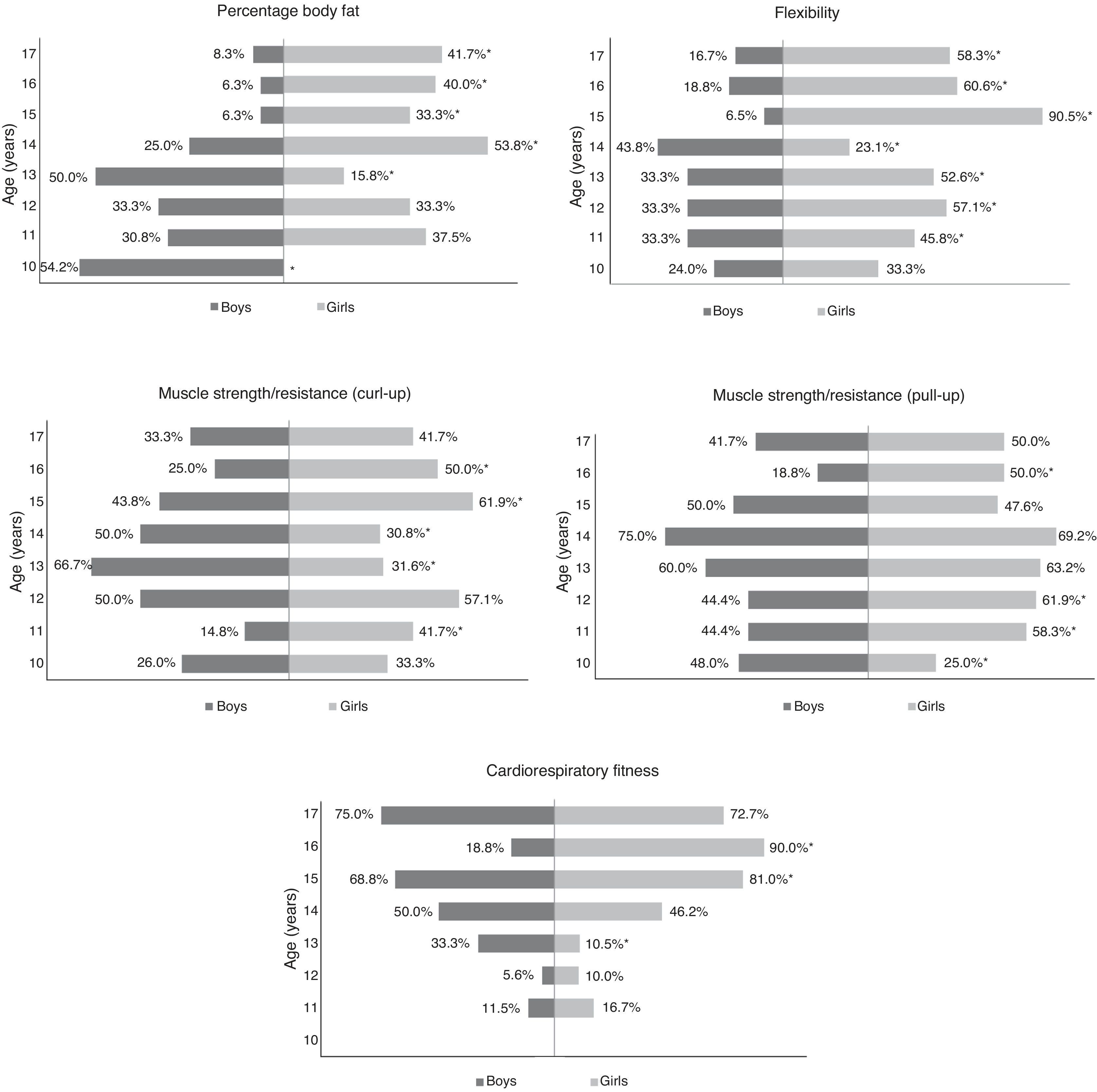

In Fig. 2, boys showed higher prevalence of percent body fat in the health risk zone at 10 (p<0.01) and 13 (p<0.01) years compared to girls. At the ages of 14 and 17 years, the prevalence was higher (p<0.01) for girls in relation to boys.

The prevalence of health risk zone in flexibility differed between the sexes at ages 11 and 17 (p<0.01) years. Girls showed higher proportions of low fitness in all ages, except for 14 years, when boys showed less fitness (Fig. 2).

In the curl-up test, higher prevalence in girls occurred at ages 11 (p<0.01), 15 (p<0.01) and 16 (p<0.01) years. For boys, higher proportions were observed at the ages of 13 (p<0.01) and 14 (p<0.01) years (Fig. 2).

In the modified pull-up test, girls showed higher prevalence of low fitness at ages 11 (p=0.03), 12 (p<0.01) and 16 (p<0.01) years, in relation to boys (p<0.05). Differences between the sexes were also observed at 10 years, with a higher proportion for boys (p<0.05) (Fig. 2).

Regarding cardiorespiratory fitness, boys showed higher prevalence of low fitness at 13 years (p<0.01), compared to girls, while in girls prevalences were higher at the ages of 15 (p=0.03) and 16 (p<0.01) years (Fig. 2).

DiscussionThe main findings of this study were higher values of TSF, SSF, body fat, and flexibility for adolescent girls compared to boys. There were differences between the sexes in each age for all components investigated, more frequently at ages above 13 years for cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition, and from 10 to 11 years for muscle fitness. In general, the prevalence of low physical fitness in percent body fat, muscle strength/endurance, and cardiorespiratory fitness were high and similar between the sexes, with differences observed for flexibility and for all physical fitness components analyzed simultaneously.

When analyzing the results of the health-related physical fitness, the girls showed a higher mean value of percent body fat than boys. The differences in body fat between ages within the same sex were found at the start and in the middle of adolescence in relation to the other ages in boys, and at the first age of this period compared to older subjects, aged 14–17 years, in girls. Mean values were higher for girls at almost all ages, similarly to what was observed in students from Brazil (seven to 15 years),23 Portugal (12–18 years9 and 10–18 years24) and Spain (12.5–17.5 years).25 These results can be explained by the disparity in the proportion of muscle mass and body fat among sexes, due to the hormonal action that occurs during puberty. In boys, the higher production of androgen hormones causes a greater increase in muscle tissue, while in girls this increase occurs in body fat, due to estrogen hormones.26

Regarding muscle fitness, girls obtained higher mean values compared to boys; however, girls flexibility remained constant as chronological age progresses, which differs from the findings for Spanish adolescents.27 Better performance in flexibility tests for teenage girls was also reported in international investigations, among European28 and German29 adolescents. In Europe, besides the fact that girls showed better flexibility than boys, there was a trend of increase for this component as age progresses,24,28,29 which was not observed in the present study. In boys, oscillations were found, with better rates at 15–16 years in relation to 14 years of age. In investigations7,30 with Brazilian adolescents, differences between ages within the same sex were not evident. The variation in flexibility rates observed in the boys from this study can be related to the growth spurt, the moment when there is a rapid development of body structures, in which bones, muscles and tendons grow at different speeds, resulting in a temporary reduction in flexibility.30 More research on this topic is needed to clarify these findings.

Regarding muscle strength/endurance (pull-up test), boys showed better performance than girls, which is in accordance with what was observed in other Brazilian studies with samples from cities of non-German colonization.5,30,31 Differences were also found between ages in both muscle strength/endurance tests for boys. The improvement in performance in muscle strength/endurance tests at ages above 13 years is explained by the onset of puberty. The sharp increase in muscle mass among boys results in an increase in muscle strength and endurance capacity as age progresses. The same happens to girls, but in a less remarkable way30. Other factors, such as low physical activity levels, not investigated in the present study, and higher body fat values may have hampered a better performance in the test among girls.

Boys showed better cardiorespiratory fitness in comparison to girls. These findings corroborate other surveys conducted in municipalities from Brazil6,30,32 Portugal24 and Spain.25,33 In the comparisons of this component between age groups, differences were found only for girls, indicating lower mean values for older girls. The changes in body composition that occur during puberty, together with chronological age, contribute to the lower mean values for this component among girls and to the higher mean values among boys.31 In addition, boys tend to be more physically active,29,33 which favors a better performance in terms of cardiorespiratory fitness compared to girls.

Concerning the prevalence of low physical fitness in body composition, one out of three adolescents showed body overweight. The data from the present study corroborate the findings observed in Januária, Brazil,5 and Spain,4 althought there is disparity in the criteria used in the studies. Researchers point out low physical activity level as one of the factors responsible for excess body fat in adolescence,10 which can have contributed to the high prevalence found in the present study. The risk of overweight/obesity in adolescents is related to low physical activity levels and to low health-related physical fitness, mainly regarding abdominal strength and cardiorespiratory fitness components.34

As for flexibility, the prevalence of low physical fitness was higher among girls. These results were also found in adolescents (14–17 years) from Januária, Brazil.5 In other words, although girls obtained higher mean values for flexibility than boys, the proportion of those who do not meet health-related criteria was also higher for female adolescents. Even if genetics favors girls,26 the less it determines flexibility, the higher the role of the environment in the maintenance of satisfactory health levels will be. Other investigations are necessary to better clarify health-related criteria for flexibility in adolescents.

The prevalences of adolescents with low physical fitness in terms of muscle strength/endurance were equal between the sexes and were similar to those observed in other Brazilian cities5 of non-German colonization. This component of muscle fitness is positively related with physical activity and resistance training33 and negatively with excess body fat.23 Thus, the prevalence of low fitness found in approximately 50% of adolescents can reflect the higher percent body fat observed in girls and the lower biceps muscle mass, supposedly present in both sexes. Such factors can have hampered the performance of the minimum number of repetitions to reach the healthy fitness zone.

The proportion of adolescents who do not meet health-related criteria for cardiorespiratory fitness did not differ between sexes. These findings differ from those verified in studies that used the previous cutoff points of FITNESSGRAM® in Florianópolis, Brazil6 and in European cities.3,25 In Europe, the prevalence of adolescents with low cardiorespiratory fitness is higher among girls.3,25 The high prevalence of girls who did not meet health-related criteria at 15 and 16 years can be explained by the increase in adipose tissue arising from the onset of maturity. However, the higher prevalence observed among boys, in the other ages, lies in the fact that the maturity process occurs later compared to girls.26 Thus, when boys get closer to post-pubertal stage, the proportions of inadequacy for this component were reduced.

Traditionally, in Brazil, due to socio-cultural implications related to an unequal treatment between sexes that can arise already in childhood, girls perform less intense physical activities than boys, which is involuntarily caused by the treatment for both sexes. This disparity lasts when children enter the school system and physical education teachers accept these differences for merely biological reasons, which reflects in the distinction between the physical activities offered to girls and boys. After puberty, girls end up engaging less in sport activities than boys. It means, because sexual maturity comes earlier in girls, body structures develop earlier in female than in male adolescents, which causes some embarrassment in teenage girls, who end up withdrawing from physical activity. Thus, girls do not benefit from the biological advantages provided by puberty in the performance of certain motor tasks.30

Regarding the overall physical fitness classification, the prevalence of adolescents with low physical fitness in all components differed between girls and boys. These proportions were lower than those found in cities with lower HDI and of non-German colonization.5 The low physical fitness levels found are directly related to adolescents’ lifestyle.10,34 The concern with the high proportion of adolescents who did not achieve the healthy physical fitness zone simultaneously in all components is related with the onset of chronic degenerative diseases in adulthood,2 to which adolescents are exposed.

Adolescents’ motivation in the performance of the tests, a variable that was not investigated in the present study, may have affected the results found, which has been one limitation of this study. Moreover, the tests used to estimate muscle fitness do not show good validity;1 however, they were used for comparison with other studies. We highlight the disparity in the method used for measuring and assessing the physical fitness components among the studies used for comparison with the findings from the present study7–9,28,29 in one or more components. The reduced number of adolescents in each age group made it difficult to locate significant differences in the comparisons between ages. Because variables related to sexual maturity, usual physical activity level, socioeconomic conditions, regional aspects, and ethnicity were not investigated in the present study, other associations and inferences were limited.

As one of the study's strengths, we can mention the representativity of the analyzed population, which allows to make inferences for the population of adolescents from São Bonifácio, Brazil, integrated into the school setting. According to data provided by the offices of the evaluated schools, there were no drop-outs in 2010, that is, the dropout rate was 0%. Besides, these results are useful for planning public policies aimed at school adolescents’ health. They can serve as parameters for health promotion strategies in school, because he identified the group of adolescents with low levels of health-related physical fitness. Additionally, the tests used for assessing adolescents’ body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness showed good validity1. Furthermore, it was possible to identify the observed physical fitness profile of students from a small town with homogeneous socio-cultural characteristics.

These results were valid for adolescents in the age group investigated and from small towns of German colonization. Further studies that investigate usual physical activity level and sexual maturity and that consider sociodemographic and cultural aspects are necessary for a better understanding of physical fitness in this setting.

In conclusion, mean values for percent body fat were higher for older girls and younger boys. Female adolescents showed higher flexibility and lower muscle strength/endurance and cardiorespiratory fitness compared to boys.

The prevalence of Brazilian adolescents from a small town of German colonization with low physical fitness was high in all components. Differences between sexes were found in the proportion of adolescents with overall low physical fitness and in the flexibility component, which is more prevalent in girls. Effective intervention programs are necessary to promote changes in the health-related physical fitness profile of these adolescents.

FundingCoordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), under process number AUXPE PROCAD/NF 110/2010.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for funding and for the scholarships granted.