Leguminous plants have received special interest for the diversity of β-proteobacteria in their nodules and are promising candidates for biotechnological applications. In this study, 15 bacterial strains were isolated from the nodules of the following legumes: Indigofera thibaudiana, Mimosa diplotricha, Mimosa albida, Mimosa pigra, and Mimosa pudica, collected in 9 areas of Chiapas, Mexico. The strains were grouped into four profiles of genomic fingerprints through BOX-PCR and identified based on their morphology, API 20NE biochemical tests, sequencing of the 16S rRNA, nifH and nodC genes as bacteria of the Burkholderia genus, genetically related to Burkholderia phenoliruptrix, Burkholderia phymatum, Burkholderia sabiae, and Burkholderia tuberum. The Burkholderia strains were grown under stress conditions with 4% NaCl, 45°C, and benzene presence at 0.1% as the sole carbon source. This is the first report on the isolation of these nodulating species of the Burkholderia genus in legumes in Mexico.

Las plantas leguminosas han recibido especial interés por la diversidad de β-proteobacteria que albergan en sus nódulos; algunas de estas bacterias son candidatas prometedoras para aplicaciones biotecnológicas. En el presente trabajo se aislaron 15 cepas bacterianas de los nódulos de las leguminosas Indigofera thibaudiana, Mimosa diplotricha, Mimosa albida, Mimosa pigra y Mimosa púdica, colectadas en 9 áreas de Chiapas, México. Las cepas fueron agrupadas en 4 perfiles de huellas genómicas por BOX-PCR e identificadas sobre la base de su morfología, pruebas bioquímicas API 20NE y secuenciación de los genes 16S ARNr, nifH y nodC como bacterias del género Burkholderia relacionadas genéticamente con Burkholderia phenoliruptrix, Burkholderia phymatum, Burkholderia sabiae y Burkholderia tuberum. Las cepas de Burkholderia crecieron en condiciones de estrés con NaCl al 4%, a una temperatura de 45°C y en presencia de benceno al 0,1% como única fuente de carbono. Este es el primer reporte del aislamiento de especies de Burkholderia nodulantes en leguminosas en México.

Genetic diversity is reflected by the existence of multiple alleles in a population, it is a necessary requirement for individuals to evolve and adapt to new conditions, ensuring the preservation of the species over time. The information on the distribution of genetic diversity has been recognized as a useful tool for the efficient design of practices for the preservation of genetic heritage. Burkholderia, Cupriavidus, and Rhizobium genera of bacteria are promising candidates for biotechnological applications. Unfortunately, many of the species of the Burkholderia and Cupriavidus genera are associated with human infections, making their applications difficult5,20. New species of diazotrophic Burkholderia have been discovered, being phylogenetically distant from the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc). Their environmental distribution and relevant features for agrobiotechnology applications are less known9,33. These genetically distinct species are grouped into a complex called non-pathogenic Burkholderia, which are atmospheric nitrogen fixers28. The presence of nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species in the rhizosphere and rhizoplane of tomato plants grown in Mexico has revealed a high degree of diversity of diazotrophic Burkholderia including Burkholderia unamae, Burkholderia xenovorans, and Burkholderia tropica, two of which are undescribed species, and one is phylogenetically related to Burkholderia kururiensis5,11. Biological Nitrogen Fixation (BNF) or other bacterial activity that takes place in the inner tissues of plants suggests that products synthesized by bacteria may be released directly into the plant, influencing its metabolism, physiology, and development21,26. Until 2001, the bacteria involved in symbiotic nodules of legume plants were reported to be restricted to the α-proteobacteria genera (Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, and Azorhizobium); however, Moulin et al.18 reported that β-proteobacteria belonging to the Burkholderia genus form nodules on legumes in Africa and South America. Chen et al.6 reported Ralstonia taiwanensis as a symbiont of Mimosa pudica in Taiwan; being this species later transferred to the Cupriavidus genus. Leguminous plants have received special interest in several countries because of their symbiotic diversity and adaptability to different soil types, which allows the microbiota associated with nodules to play an important role in nutrition and development1,4,8,22. However, there are few studies on the isolation of bacteria of the Burkholderia genus in legumes in Mexico. Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify Burkholderia nodulating wild legumes in Chiapas, Mexico.

Materials and methodsSample collectionRoot nodules were collected from the following leguminous plants: Indigofera thibaudiana, Mimosa diplotricha, Mimosa albida, Mimosa pigra, and M. pudica in different geographical sites of Chiapas, Mexico. Soil pH was measured by adding 10g of soil in 100ml of distilled water while stirring for 30min2.

Bacterial strains and culture conditionThe nodules collected were washed and immersed in 70% ethanol for 5min, then they were disinfected with sodium hypochlorite at 25% for 15min. The excess hypochlorite was removed by rinsing with sterile distilled water. Finally, the disinfected nodules were macerated and resuspended in a solution of MgSO4·7H2O at 10mM32. Then, 100μl of the suspension was inoculated into Burkholderia Azelaic citrullina (BAc) agar culture media and Yeast extract Mannitol Agar (YMA) culture media. The inoculated Petri dishes were incubated at 29°C for 2 days and colonies with different morphology were then selected.

Gram stainingGram-staining reaction was carried out by using a loopful of pure culture grown on Tryptone agar, which was then stained using the standard Gram staining procedure27.

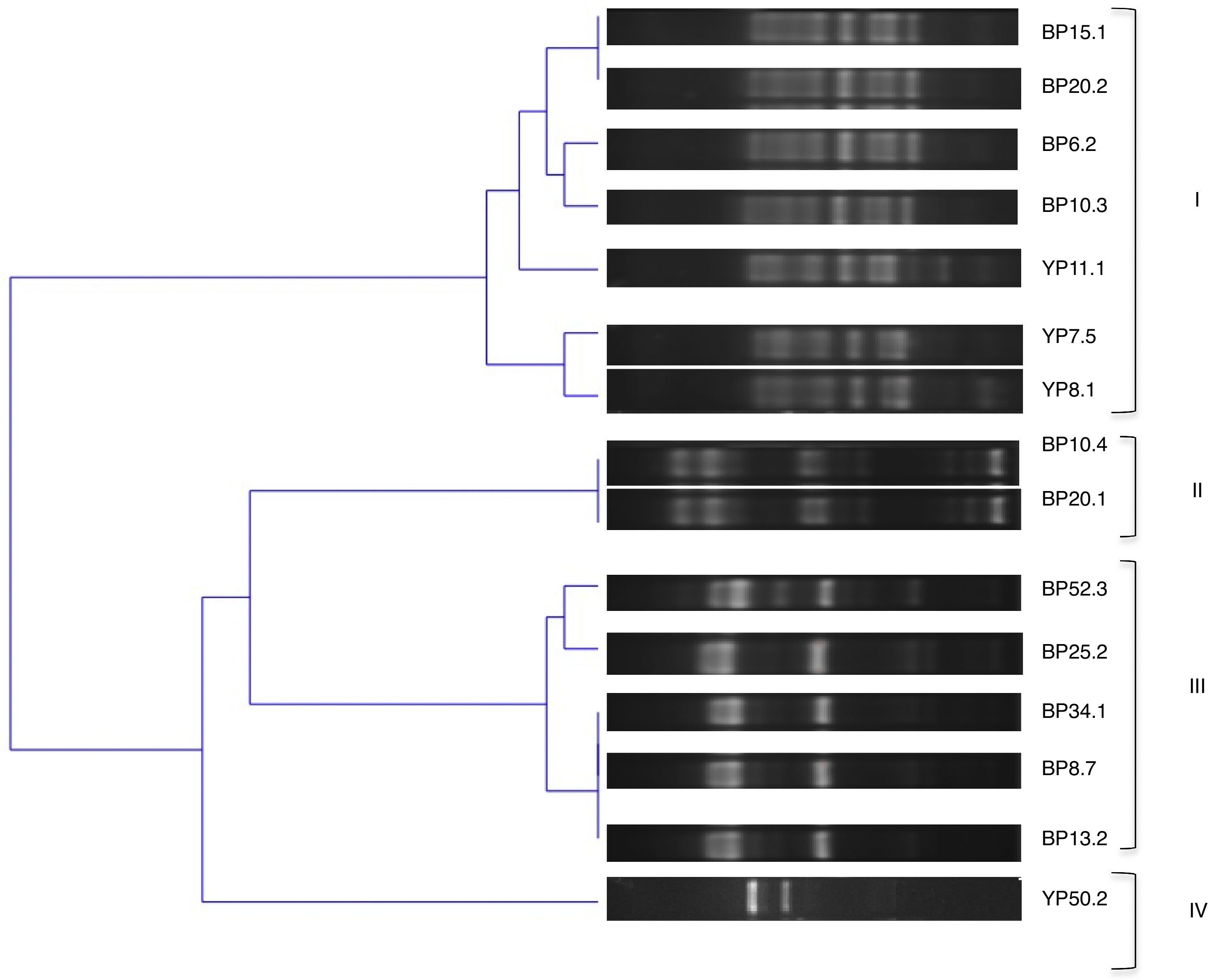

Box-PcrThe BOX element (BOXA1) was amplified using the BOXA1R primer. Cycling conditions for BOX-PCR were as follows: 95°C for 5min and then 35 cycles of 95°C for 1min, 63°C for 1min and 72°C for 3min, and a final elongation cycle for 10min at 72°C. PCR and electrophoresis conditions were according to Estrada-de los Santos et al.10

16S rRNA, nifH and nodC gene sequencingOne strain of each group of the BOX-PCR profile was selected for its identification. The DNA extraction of the selected isolates was performed with the ZR Fungal/Bacterial DNA Miniprep™ kit. Subsequently, the 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using fD1 and rD1 oligonucleotides31. The nifH and nodC genes were amplified in the isolated strains by PCR using different oligonucleotides3,15. The PCR products from 16S rRNA, nifH and nodC genes were cloned and the sequences were determined by the Institute of Biotechnology of the UNAM. The phylogenetic trees, based on 16S rRNA, nodC, and nifH genes were constructed by the neighbor-joining method14 using the Tamura-Nei model in Mega software version 629. Multiple alignments of the sequences were performed using CLUSTALW software30, based on 1400 nucleotide sites for the 16S rRNA gene, 316 nucleotide sites for the nifH gene and 600 nucleotide sites for the nodC gene.

Biochemical characterizationThe isolated strains were analyzed using the API 20NE microtest systematic gallery (bioMérieux) to identify their metabolic characteristics.

Saline and thermal stress testsThe strains identified as Burkholderia were grown in culture media containing 2 and 4% NaCl. For the thermal stress test, the strains were incubated at temperatures of 37 and 45°C for 4 days7.

Aromatic compound growthThe strains identified as Burkholderia were grown in salts-ammonium-aromatic compound (SAAC) culture media containing phenol and benzene at 0.1% as sole carbon source5.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbersThe obtained 1400-bp portion of the 16S rRNA gene sequences in this study was deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KY569371, KY569372, KY569373 and KY569374. The nifH sequences were deposited under accession numbers KY574497, KY574498, KY574499 and KY574500, and the nodC sequences under accession numbers KY574501, KY574502 and KY574503.

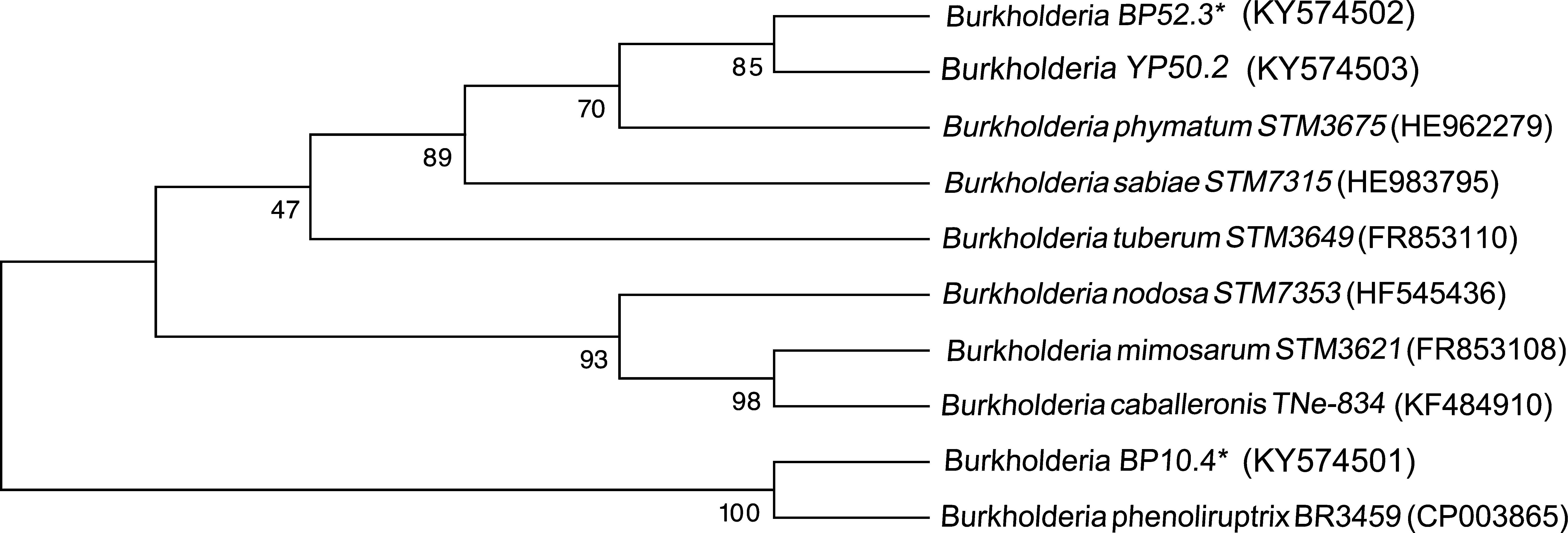

ResultsIsolationAll the plants examined had nodules on their roots, and fifteen strains were obtained; isolates were selected from the highest tenfold serial dilutions using the predominance of the morphological colony types (Table 1). The strains were characterized as gram- negative, oxidase-negative, and catalase-positive bacilli.

Isolated strains from different leguminous plants in the state of Chiapas, Mexico

| Code strains | Leguminous plant | Locality | Soil pH |

|---|---|---|---|

| BP10.4, YP8.7, BP6.2, BP10.3, YP11.1, YP7.5, YP8.1 | Mimosa pigra | Tapachula | 5.3–8.7 |

| BP20.1, BP15.1, BP20.2, YP13.2 | Mimosa pigra, Mimosa diplotricha | Mazatán | 5.4–7.4 |

| BP52.3, YP50.2 | Mimosa albida, Indigofera thibaudiana | Tonalá | 7.0–7.8 |

| BP25.2 | Mimosa pudica | Huehuetán | 5.2–7.1 |

| BP34.1 | Indigofera thibaudiana | Huixtla | 7.5–8.2 |

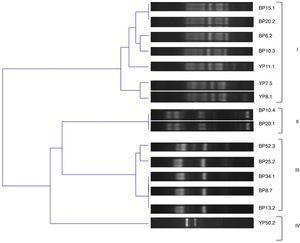

The genetic diversity of the isolates was further analyzed by BOX-PCR, amplification products yielded complex genomic fingerprints consisting of fragments ranging in size from 100 to 1000bp. A binary matrix was constructed with the BOXA1R profiles of the analyzed strains; they were divided into 4 groups based on the UPGMA method using Jaccard's coefficient with a cut of 70% (Fig. 1).

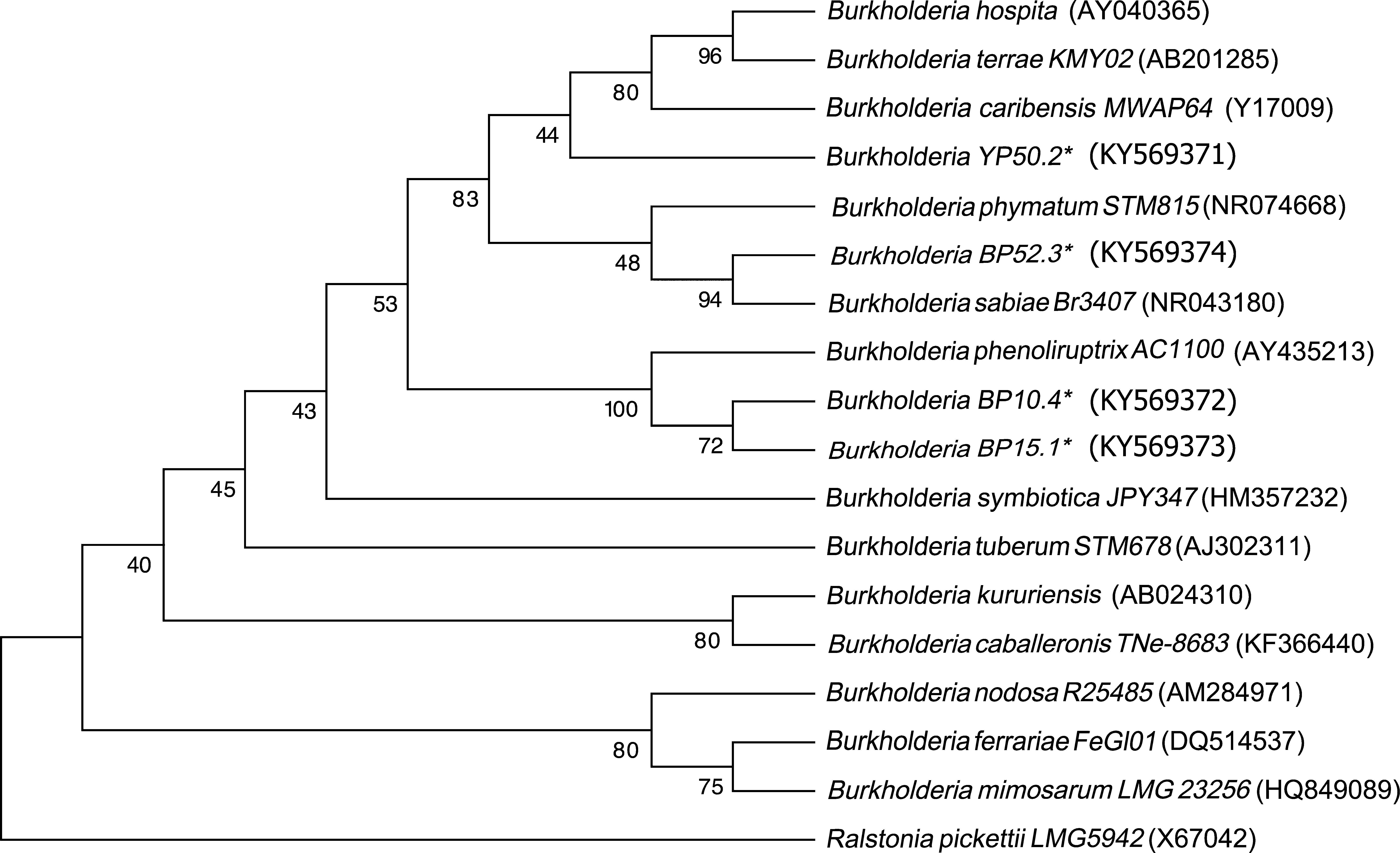

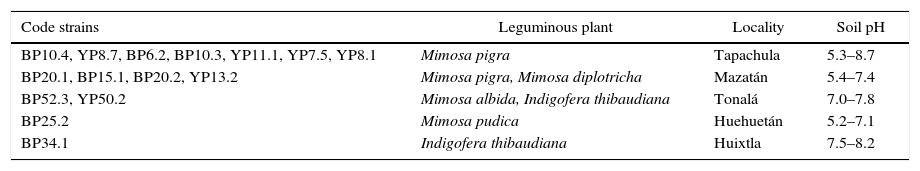

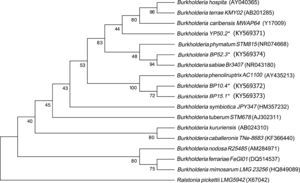

Sequencing of the 16S Ribosomal RNAThe sequences obtained from each of the strains were compared against the GenBank nucleotide database. The four strains were genetically related to the Burkholderia genus. The analysis placed YP50.2 (KY569371) strain close to Burkholderia phymatum STM815 (99%, NR074668), BP52.3 (KY569374) strain to Burkholderia sabiae (99%, NR043180), while the BP15.1 (KY569373) and BP10.4 (KY569372) strains were placed close to Burkholderia phenoliruptrix (99%, AY435213). The genetic relatedness of the isolated species strains with reported nodulating Burkholderia spp. can be seen in the phylogenetic tree constructed using the neighbor-joining method23, based on 1400 nucleotides of the 16S ribosomal gene sequences according to the distance matrix developed by Jukes and Cantor14 (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, showing the relatedness among the nodulating Burkholderia species. The bar represents 1 nucleotide substitution per 100 nucleotides. Nodal robustness of the tree was assessed using 1000 bootstrap replicates. The NCBI GenBank accession number for each strain type tested is shown in parentheses. Phylogenetic relationship of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of isolates of Burkholderia phenoliruptrix, Burkholderia caribensis and Burkholderia sabiae in leguminous plants.

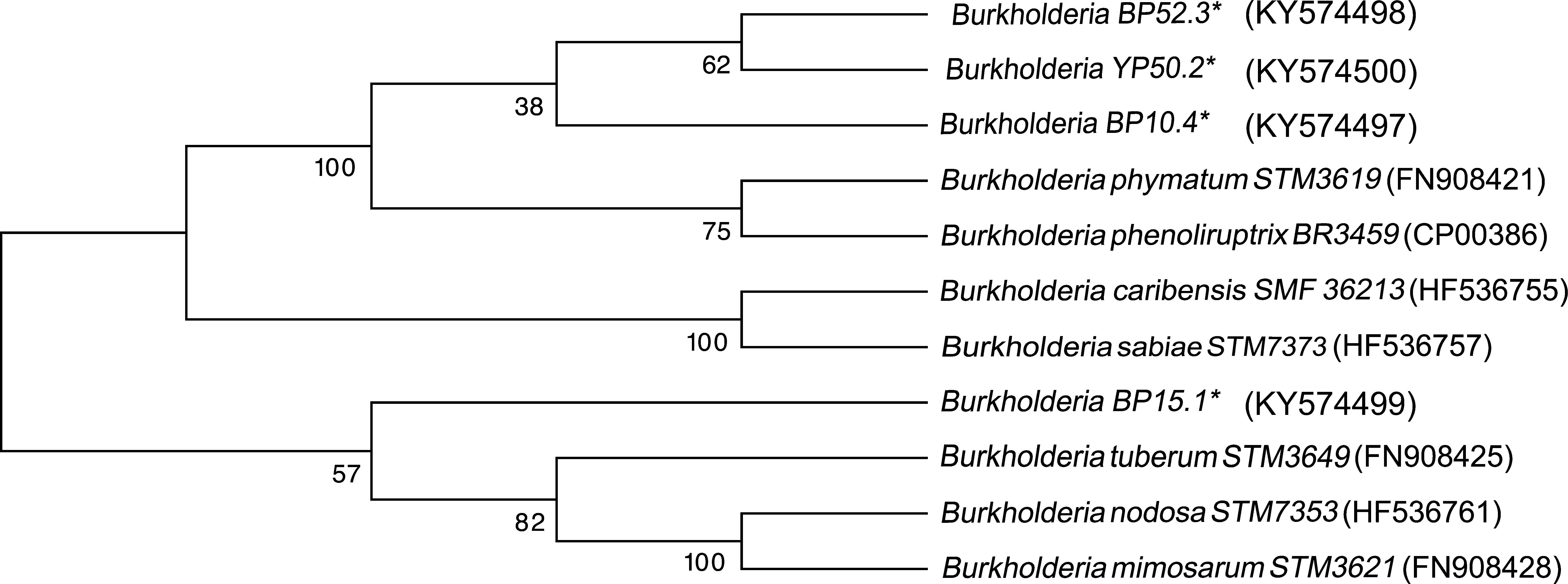

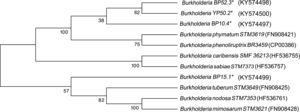

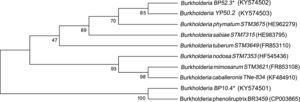

Four strains of Burkholderia spp. were chosen for the sequencing of their nifH and nodC genes based upon their different lineages; partial nifH gene sequences encoding dinitrogenase reductase, a key enzyme in N2 fixation, were determined, and the phylogenies of the obtained sequences were compared with the nifH sequences in the databases (Fig. 3). The analysis placed BP52.3 (KY574498), YP50.2 (KY574500) and BP10.4 (KY574497) strains close to B. phymatum STM815 (with 90–97% similarity, NR074668) and BP15.1 (KY574499) strain close to Burkholderia sp. STM (93%, FN544053). The phylogenetic analysis of the partial nodC gene sequences of BP52.3 (KY574502) and YP50.2 (KY574503) strains placed them close to B. phymatum STM815 (99%, NR074668) and the BP10.4 strain to B. phenoliruptrix (99%, AY435213) (Fig. 4). The genetic relationship of the isolated Burkholderia species with nodulating Burkholderia spp. strains described above can be seen in the phylogenetic tree constructed using the neighbor-joining method23, based on 316 nucleotides of the nifH gene sequences and 600 nucleotides of the nodC gene, according to the distance matrix proposed by Jukes and Cantor14.

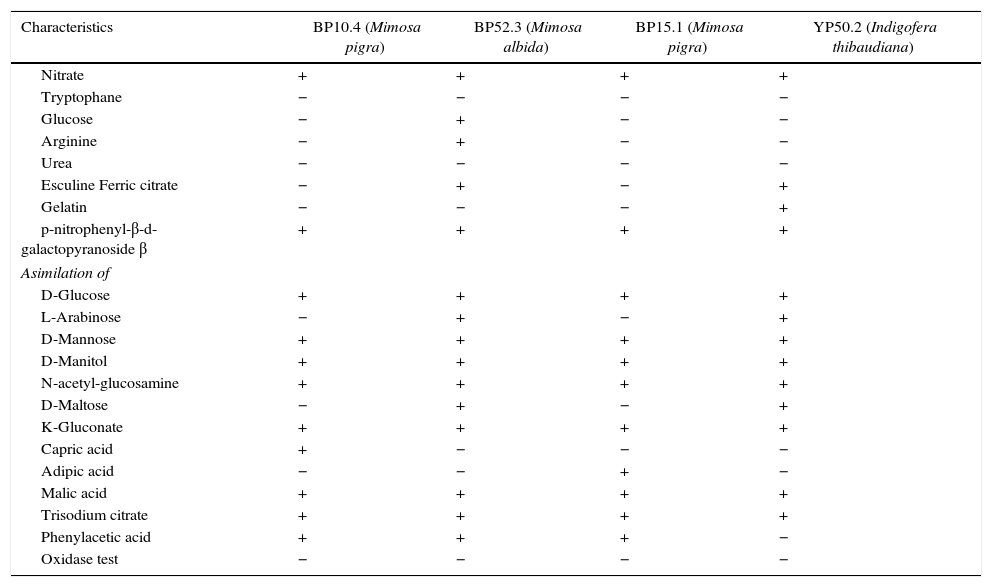

The four selected strains exhibited different metabolic characteristics in the use of carbon sources (Table 2).

Biochemical characteristics of Burkholderia isolates from leguminose of state of Chiapas, Mexico

| Characteristics | BP10.4 (Mimosa pigra) | BP52.3 (Mimosa albida) | BP15.1 (Mimosa pigra) | YP50.2 (Indigofera thibaudiana) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate | + | + | + | + |

| Tryptophane | − | − | − | − |

| Glucose | − | + | − | − |

| Arginine | − | + | − | − |

| Urea | − | − | − | − |

| Esculine Ferric citrate | − | + | − | + |

| Gelatin | − | − | − | + |

| p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside β | + | + | + | + |

| Asimilation of | ||||

| D-Glucose | + | + | + | + |

| L-Arabinose | − | + | − | + |

| D-Mannose | + | + | + | + |

| D-Manitol | + | + | + | + |

| N-acetyl-glucosamine | + | + | + | + |

| D-Maltose | − | + | − | + |

| K-Gluconate | + | + | + | + |

| Capric acid | + | − | − | − |

| Adipic acid | − | − | + | − |

| Malic acid | + | + | + | + |

| Trisodium citrate | + | + | + | + |

| Phenylacetic acid | + | + | + | − |

| Oxidase test | − | − | − | − |

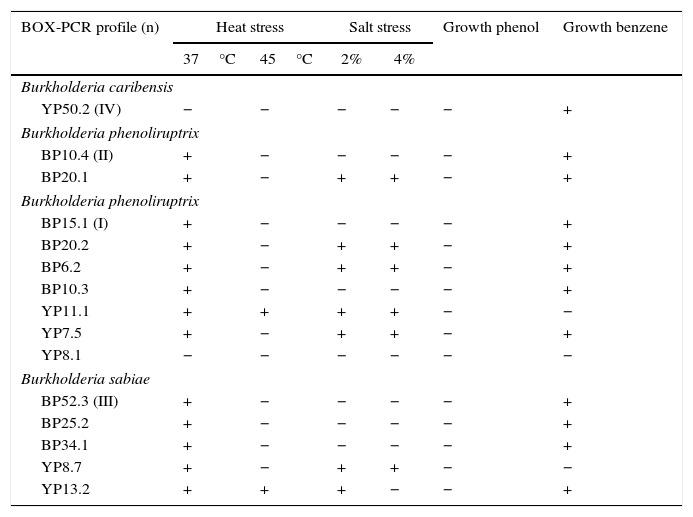

The strain Burkholderia spp. BP15.1, which is closely related to B. phenoliruptrix, grew in culture media containing 2 and 4% NaCl, and also at temperatures of 37°C and 45°C respectively. Nonetheless, the other 6 strains belonging to the same group did not exhibit the same behavior in the stress tests, which is contrary to the degradation of benzene (Table 3). The strain Burkholderia spp. YP50.2, which is closely related to Burkholderia caribensis, did not grow in high salinity and temperature conditions; however, it did use benzene as a carbon source for growth, while The strain Burkholderia sp. BP52.3, which is closely related to B. sabiae, did not grow under stress conditions at 45°C; it only used benzene as a carbon source, while Burkholderia spp. BP10.4 metabolically behaved much like Burkholderia spp. BP52.3 (Table 3).

Burkholderia strains growth in stress and aromatic compounds

| BOX-PCR profile (n) | Heat stress | Salt stress | Growth phenol | Growth benzene | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37°C | 45°C | 2% | 4% | |||

| Burkholderia caribensis | ||||||

| YP50.2 (IV) | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Burkholderia phenoliruptrix | ||||||

| BP10.4 (II) | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| BP20.1 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Burkholderia phenoliruptrix | ||||||

| BP15.1 (I) | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| BP20.2 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| BP6.2 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| BP10.3 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| YP11.1 | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| YP7.5 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| YP8.1 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Burkholderia sabiae | ||||||

| BP52.3 (III) | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| BP25.2 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| BP34.1 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| YP8.7 | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| YP13.2 | + | + | + | − | − | + |

The main objective of this work was to explore the presence of Burkholderia species in Southeastern Mexico. The strains isolated from nodules of I. thibaudiana, M. diplotricha, M. albida, M. pigra, and M. pudica plants, in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, were selected based on their morphological characteristics. The 15 strains were grouped into 4 genomic fingerprint profiles obtained by BOX-PCR. One strain of each profile was selected for sequencing. The 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained were analyzed in the GenBank nucleotide database; all 4 strains were genetically related to species of the Burkholderia genus. Strain YP50.2 (KY569371), which is genetically related to the B. caribensis species, was isolated in the YMA culture medium from I. thibaudiana nodules collected in the municipality of Tonala. Strain BP52.3 (KY569374), isolated in BAc culture medium from the plant M. albida collected in the town of Tonala has a genetic relationship with B. sabiae. Strain BP15.1 (KY569373), which was isolated in BAc culture medium from M. pigra nodules collected in the municipality of Mazatan and BP10.4 (KY569372) strain also isolated from M. pigra in the municipality of Tapachula have a genetic relationship with B. phenoliruptrix. In the analysis of the sequences of the nifH genes of Burkholderia YP50.2 (KY574500), BP52.3 (KY574498), and BP10.4 (KY574498) strains, a genetic relationship was found with B. phymatum and B. phenoliruptrix, while strain BP15.1 (KY574499) was related to B. sabiae and Burkholderia tuberum (Fig. 3). The same genetic relationship was observed in the sequence analysis of the nodC genes; Burkholderia BP52.3 (KY574502) and YP50.2 (KY574503) strains are related with B. phymatum and B. phenoliruptrix, while the BP10.4 (KY574501) strain has a genetic relationship with B. sabaie and B. tuberum (Fig. 4).

In the sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA, nifH and nodC genes of Burkholderia spp. strains, it can be observed that there is a genetic relationship with the nodulating species already described; however, it can also be observed that in the nifH and nodC gene sequences the strains isolated from leguminous plants might be new species of Burkholderia. Burkholderia spp. strains have the capacity to metabolize different carbon sources, which is a metabolic characteristic of the genus (Table 2). Therefore, to confirm whether they are new species, the gene sequencing will be done on the atpD, recA, and rpoB genes, as well as the protein profiles and DNA hybridization tests with species that have greater genetic relationship to confirm that these strains belong to new Burkholderia species. The description of few nodulating Burkholderia species was done in Mexico; among these species is Burkholderia caballeronis which was isolated from the rhizosphere of the tomato plant, which is not a legume, and Burkholderia spp. CCGE1002, isolated from nodules of Mimosa occidentalis17,19. It is also important to note that although B. phenoliruptrix was isolated from nodules of Mimosa flocculosa in Brazil, this is the first report of this species isolated from nodules of M. pigra in Mexico3,6,12,13,24,25. In Mexico, it is the first report of these Burkholderia species genetically related to B. phymatum, B. phenoliruptrix, B. sabiae, B. caballeronis, and B. tuberum.

The Burkholderia spp. strains were subjected to various stress conditions, they grew in the presence of benzene at 0.1% as the only carbon source, and also at 2 and 4% NaCl and temperatures of 37 and 45°C. Most Burkholderia spp. strains were tolerant to heat and salinity stress conditions, and also had the ability to grow in 0.1% benzene. This ability of tolerance to saline and thermal stress has been evaluated in strains of rhizobia7. Lopez et al.16 evaluated the ability of Rhizobium tropici to degrade polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Caballero-Mellado et al.5 reported on nitrogen-fixing strains B. unamae and B. xenovorans growing in the presence of phenol, benzene, and biphenyl. Furthermore, species of the B. cepacia complex, such as B. cepacia G4, degrade toluene. This work contributes to confirming the ability of the members of nodulating- Burkholderia species to degrade some xenobiotic compounds.

In conclusion, members of the Burkholderiaceae family, particularly of the genus Burkholderia, were identified in Mexico. This genus was found in nodules of leguminous plants growing in Chiapas State. However, the presence of Burkholderia seems to be limited, as only a few strains were identified among the isolates analyzed.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) and Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) from Mexico, for the financial support for the development of this research project number 179540.