Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of severe invasive disease associated with high mortality and morbidity worldwide. To identify the serotypes most commonly associated with infection in adults in Argentina, 791 pneumococcal isolates from 56 hospitals belonging to 16 provinces and Buenos Aires city were serotyped. The isolates were submitted as part of a National Surveillance Program for invasive pneumococcal disease in adults, which started in 2013. Serotypes 3, 8, 12F, 7F and 1 were the most prevalent among adult patients. During the study period there was no significant difference in serotype distribution between the age groups studied (18–64 and ≥65 years old), except for serotype 1, 3 and 23A. Most prevalent serotypes in pneumonia were serotype 7F, 1, 12F, 8, and 3. When the clinical diagnosis was meningitis, serotype 3 and 12F were the most prevalent, whereas when the diagnosis was sepsis/bacteremia the most prevalent was serotype 8. In this work, for the 18–64-year-old group, PPSV23 and PCV13 serotypes accounted for 74.56% and 44.54% respectively of the cases in the studied period. On the other hand, for the ≥65-year-old group, these serotypes represented 72.30% and 41.42% respectively. The aim of this work was to establish the knowledge bases of the serotypes that cause invasive pneumococcal diseases in the adult population in Argentina and to be able to detect changes in their distribution over time in order to explore the potential serotype coverage of the vaccines in current use.

Streptococcus pneumoniae es una causa importante de enfermedad invasiva grave asociada con una alta mortalidad y morbilidad en todo el mundo. Para identificar los serotipos principales asociados con la infección en adultos en Argentina, 791 aislamientos de neumococo de 56 hospitales pertenecientes a 16 provincias y la ciudad de Buenos Aires fueron serotipificados. Los aislamientos fueron remitidos como parte del Programa Nacional de Vigilancia para la enfermedad neumocócica invasiva en adultos, que comenzó en 2013. Los serotipos 3, 8, 12F, 7F y 1 fueron los más prevalentes. Durante el período de estudio no hubo diferencias significativas en la distribución de serotipos entre los dos grupos de adultos estudiados (18-64 y ≥65 años), excepto para los serotipos 1, 3 y 23A. Los serotipos más prevalentes en casos de neumonía fueron 7F, 1, 12F, 8 y 3. Cuando el diagnóstico clínico fue meningitis, los serotipos 3 y 12F fueron los más prevalentes. Y el serotipo 8 fue el más prevalente en la sepsis/bacteriemia. En el grupo de 18-64 años, los serotipos PPSV23 y PCV13 representaron, respectivamente, el 74,56 y el 44,54% de los casos de enfermedad invasiva en el período estudiado. En el grupo de ≥65 años, estos serotipos representaron el 72,30 y 41,42%, respectivamente. Es importante conocer los serotipos causantes de infecciones neumocócicas invasivas en la población adulta en Argentina y detectar eventuales cambios en su distribución a lo largo del tiempo, para explorar la potencial cobertura de las vacunas utilizadas.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (Spn) is an important pathogen that causes invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD)20. IPD incidence rates and the predominant serotypes may also vary due to the patient's demographics and vaccination status8,18,19. As a result, it is important that countries conduct continuous surveillance of serotype distribution and incidence rates in order to detect and report regional differences and to monitor the effect of vaccination.

The primary virulence factor of this pathogen is the polysaccharide capsule, which is crucial for immune evasion; an extensive study of the capsule has led to the identification of 97 capsular serotypes6.

Since 2013, a National IPD Surveillance Program for adults has been implemented in Argentina. The main objectives of this network are to monitor the circulation of S. pneumoniae serotypes, and to determine antibiotic resistance.

In Argentina in 2012, the Ministry of Health (MH) introduced into the national immunization schedule the 13-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV13) for children under 2 years of age and continued with the vaccination of older adults and individuals at risk with a 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PSSV23). To further strengthen this strategy, the MH, following the recommendation of the National Commission of Immunizations, decided to add the PCV13 vaccine for individuals between 5 and 64 years old belonging to vulnerable groups and those over 65 years old through a sequential scheme3.

The aim of this study was to define the serotype distribution of S. pneumoniae causing invasive disease in Argentinean adults ≥18 years old, and to explore the potential of serotype coverage of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in the last 5 years (2013–2017).

Materials and methodsS. pneumoniae isolates from classic sterile fluids (blood, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, ascitic fluid, joint fluid) and other sites (bone, placenta, skin) in adults ≥18 years old (interquartile range:18–100) were collected from 56 hospitals belonging to 16 provinces and Buenos Aires city, between January 2013 and December 2017. Isolates were submitted to the National Reference Laboratory, INEI-ANLIS “Dr. Carlos G. Malbrán”, where the Neufeld-Quellung reaction was performed using pool, group, type and factor specific commercial antisera produced by the Statens Serum Institute (Copenhagen, Denmark); capsular types were designated in accordance with the Danish nomenclature system. Isolates whose serotypes could not be determined by a Quellung reaction were confirmed by the PCR technique1. Isolates were classified as non-typeable (NT) only if the Quellung reaction or PCR were unable to categorize them as one of the 97 known serotypes.

Analysis was based on the serotypes included in the 13-valent conjugate vaccine (1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 23F) and the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F). Two age groups were evaluated: 18–64 years old and ≥65 years old.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad QuickCalcs and WHONET 5.6 (WHO). The results expressed in percentage are reported with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Differences in serotype distribution between the different parameters were assessed for statistical significance (p<0.05) using the Chi square test and the Fisher exact test.

As we could not get any vaccine coverage data from the records, we theorized and correlated it with the serotypes found; then, we sought to relate each serotype identified in the sample to the potential coverage of the vaccines available in Argentina.

ResultsSeven hundred and ninety-one S. pneumoniae isolates were obtained. The distribution of isolates (n) was: 2013 (209), 2014 (142), 2015 (146), 2016 (145) and 2017 (149).

With regard to clinical diagnoses, the distribution in order of relevance was: pneumonia (68.14%), sepsis/bacteremia (12.76%), meningitis (12.52%), others (6.58%).

Serotyping was performed in 791 S. pneumoniae isolates, and 61 serotypes were identified.

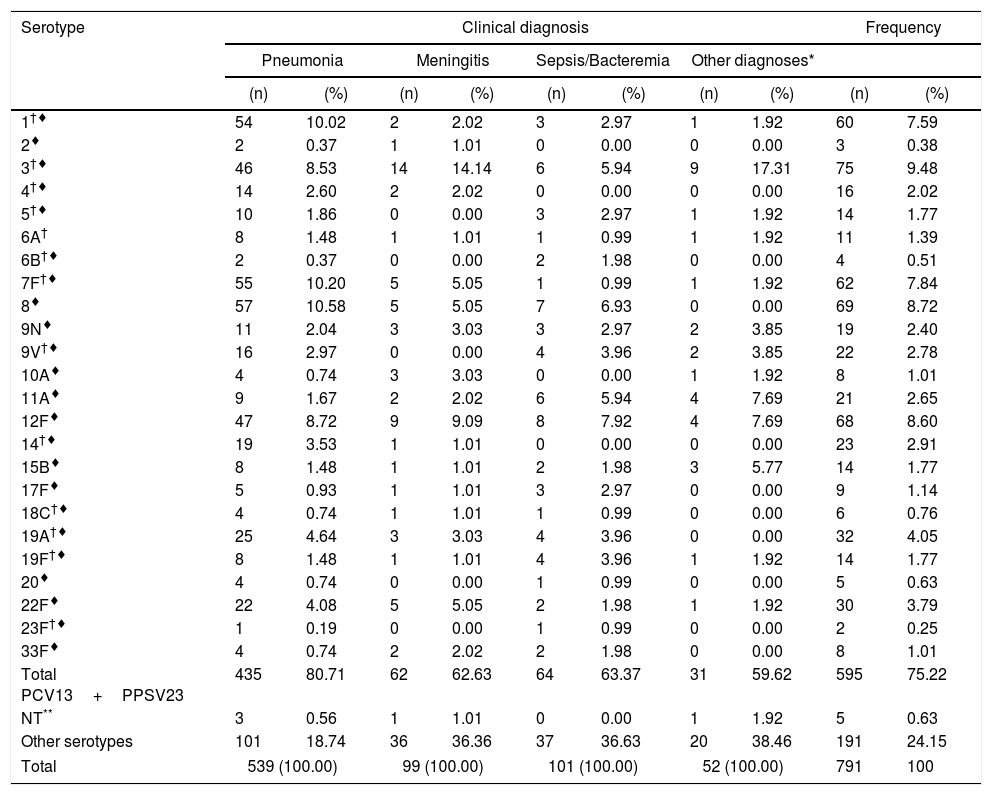

The distribution of S. pneumoniae serotypes (included in both vaccines) according to the main clinical diagnosis are summarized in Table 1.

Distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes according to main clinical diagnosis (2013–2017).

| Serotype | Clinical diagnosis | Frequency | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | Meningitis | Sepsis/Bacteremia | Other diagnoses* | |||||||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| 1†♦ | 54 | 10.02 | 2 | 2.02 | 3 | 2.97 | 1 | 1.92 | 60 | 7.59 |

| 2♦ | 2 | 0.37 | 1 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.38 |

| 3†♦ | 46 | 8.53 | 14 | 14.14 | 6 | 5.94 | 9 | 17.31 | 75 | 9.48 |

| 4†♦ | 14 | 2.60 | 2 | 2.02 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 16 | 2.02 |

| 5†♦ | 10 | 1.86 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 2.97 | 1 | 1.92 | 14 | 1.77 |

| 6A† | 8 | 1.48 | 1 | 1.01 | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1.92 | 11 | 1.39 |

| 6B†♦ | 2 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 1.98 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.51 |

| 7F†♦ | 55 | 10.20 | 5 | 5.05 | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1.92 | 62 | 7.84 |

| 8♦ | 57 | 10.58 | 5 | 5.05 | 7 | 6.93 | 0 | 0.00 | 69 | 8.72 |

| 9N♦ | 11 | 2.04 | 3 | 3.03 | 3 | 2.97 | 2 | 3.85 | 19 | 2.40 |

| 9V†♦ | 16 | 2.97 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 3.96 | 2 | 3.85 | 22 | 2.78 |

| 10A♦ | 4 | 0.74 | 3 | 3.03 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.92 | 8 | 1.01 |

| 11A♦ | 9 | 1.67 | 2 | 2.02 | 6 | 5.94 | 4 | 7.69 | 21 | 2.65 |

| 12F♦ | 47 | 8.72 | 9 | 9.09 | 8 | 7.92 | 4 | 7.69 | 68 | 8.60 |

| 14†♦ | 19 | 3.53 | 1 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 23 | 2.91 |

| 15B♦ | 8 | 1.48 | 1 | 1.01 | 2 | 1.98 | 3 | 5.77 | 14 | 1.77 |

| 17F♦ | 5 | 0.93 | 1 | 1.01 | 3 | 2.97 | 0 | 0.00 | 9 | 1.14 |

| 18C†♦ | 4 | 0.74 | 1 | 1.01 | 1 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 0.76 |

| 19A†♦ | 25 | 4.64 | 3 | 3.03 | 4 | 3.96 | 0 | 0.00 | 32 | 4.05 |

| 19F†♦ | 8 | 1.48 | 1 | 1.01 | 4 | 3.96 | 1 | 1.92 | 14 | 1.77 |

| 20♦ | 4 | 0.74 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 0.63 |

| 22F♦ | 22 | 4.08 | 5 | 5.05 | 2 | 1.98 | 1 | 1.92 | 30 | 3.79 |

| 23F†♦ | 1 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.25 |

| 33F♦ | 4 | 0.74 | 2 | 2.02 | 2 | 1.98 | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 1.01 |

| Total PCV13+PPSV23 | 435 | 80.71 | 62 | 62.63 | 64 | 63.37 | 31 | 59.62 | 595 | 75.22 |

| NT** | 3 | 0.56 | 1 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.92 | 5 | 0.63 |

| Other serotypes | 101 | 18.74 | 36 | 36.36 | 37 | 36.63 | 20 | 38.46 | 191 | 24.15 |

| Total | 539 (100.00) | 99 (100.00) | 101 (100.00) | 52 (100.00) | 791 | 100 | ||||

† Serotypes included in PCV13. ♦ Serotypes included in PPSV23. Pneumonia: isolates from blood and pleural liquid. Meningitis: isolates from CSF. Sepsis/bacteremia: isolates from blood without focus.

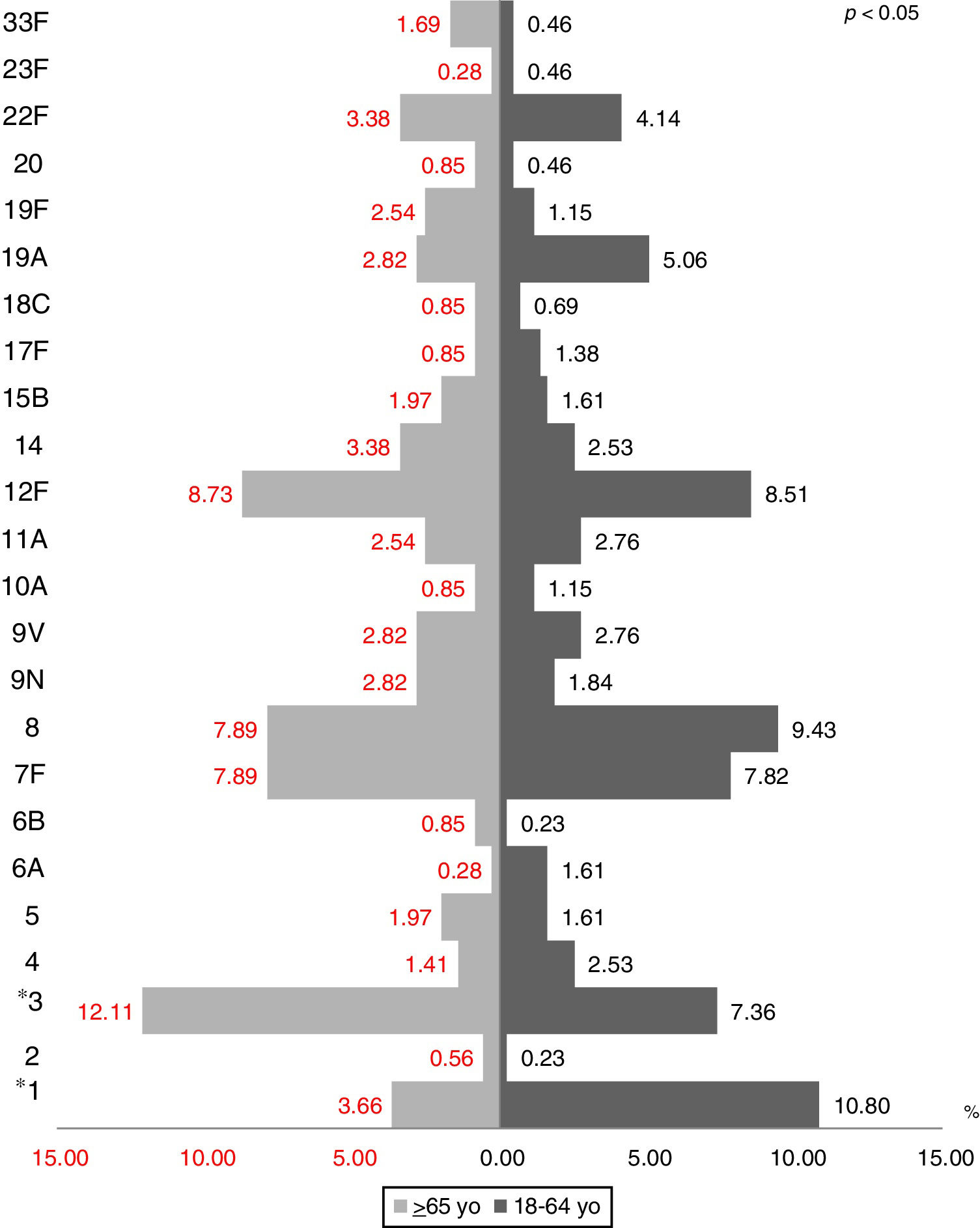

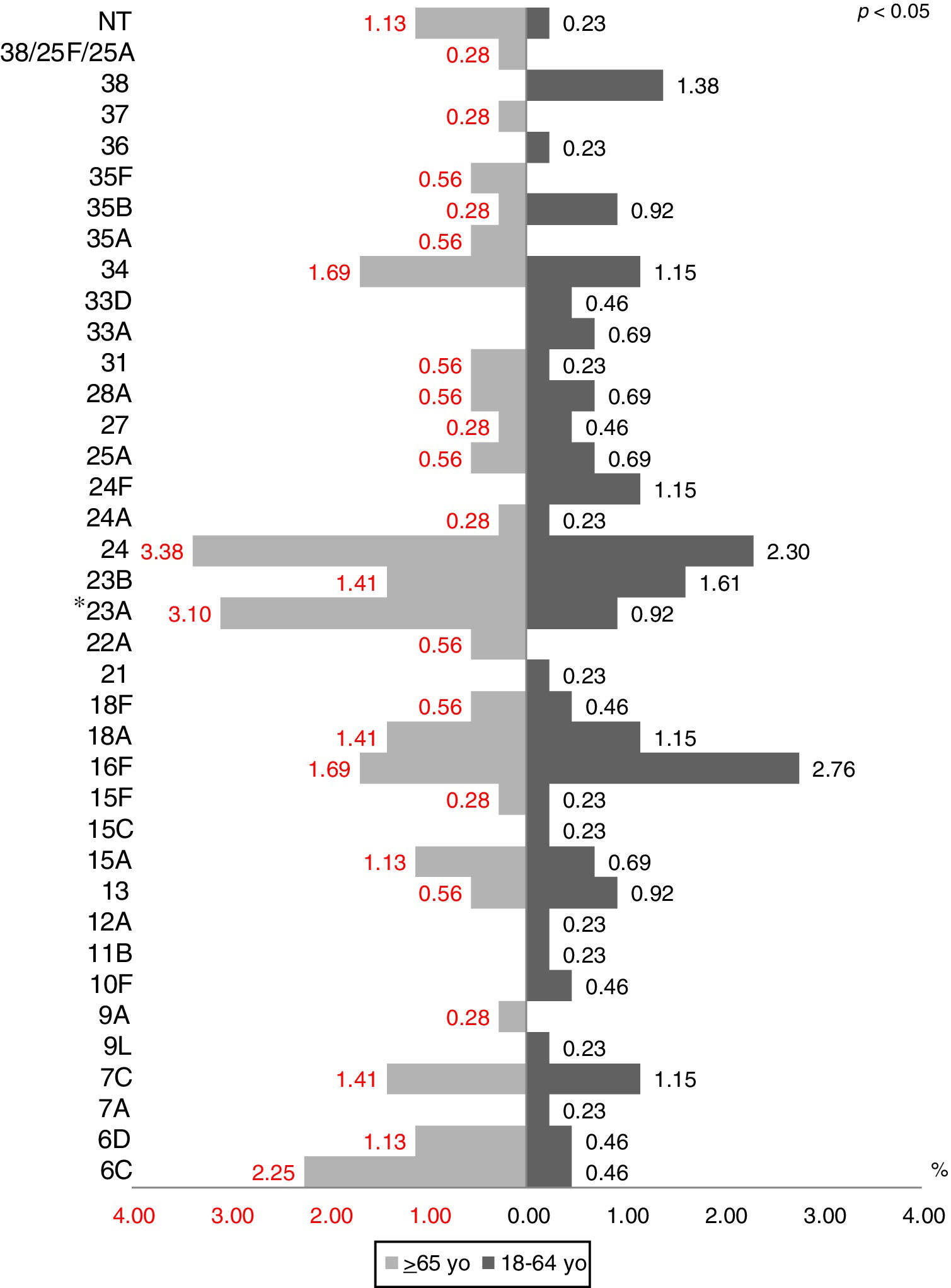

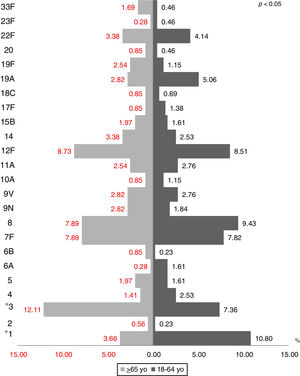

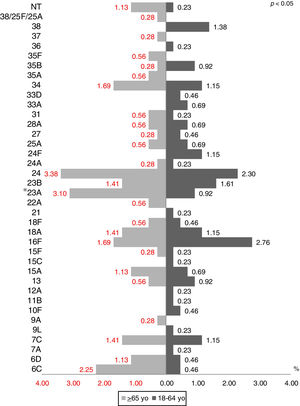

The most prevalent serotypes were 3 (9.48%), 8 (8.72%), 12F (8.60%), 7F (7.84%), and 1 (7.59%). During the period of study there was no significant difference in serotype distribution between the two groups studied, except for serotypes 1 (p=0.0001), 3 (p=0.022) and 23A (p=0.025) (Figs. 1 and 2).

The most prevalent serotypes in pneumonia were serotypes 7F, 1, 12F, 8, and 3. When we attempted to find if there was an association between these serotypes and pneumonia with respect to other clinical diagnoses, the differences were statistically significant, only for serotype 8, odds ratio (OR) 17.67 (95% CI: 4.29–72.73), p<0.0001; serotype 1, odds ratio (OR) 4.54 (95% CI: 1.92–10.71), p<0.0005; serotype 7F, odds ratio (OR) 3.96 (95% CI: 1.77–8.82), p=0.0008 and serotype 3, odds ratio (OR) 0.21 (95% CI: 0.14–0.32), p<0.0001. The association between serotype 12F and pneumonia was not statistically significant.

The capsular types more prevalent in meningitis cases were 3 and 12F, while serotype 8 was the most prevalent in sepsis/bacteremia cases. In both diagnoses the differences were not statistically significant.

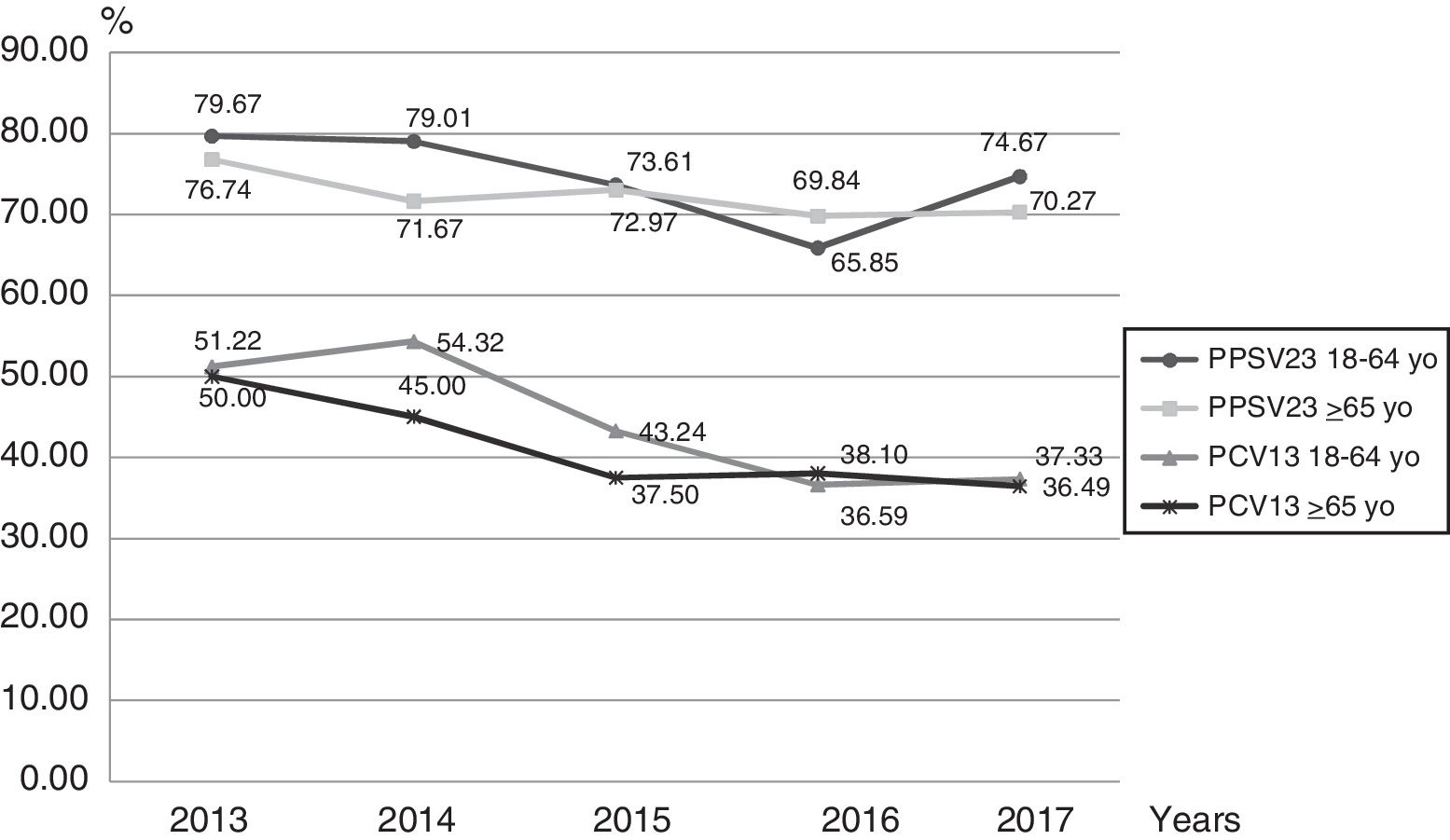

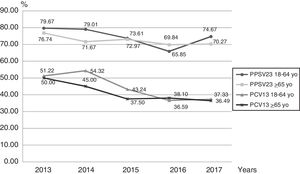

Based on serotype distribution, we calculated the theoretical coverage for both vaccines (Fig. 3). Serotypes included in the PCV13 and PPSV23 formulation were found in 41.34% (327/791) and 73.83% (584/791) of the infections, if we combined both vaccines the value rose to 75.22% (595/791). In this work, for the 18–64 year-old group, PPSV23 and PCV13 serotypes accounted for 74.56% and 44.54% respectively of the cases in the studied period. On the other hand, for the ≥65-year-old group, these serotypes represented 72.30% and 41.42% respectively.

DiscussionThis work summarizes the local serotype distribution of S. pneumoniae associated with IPD in adults in Argentina. Notwithstanding that the sample size was small, we consider that the trends reported in this paper are a reliable reflection of serotypes associated with IPD in Argentina and establish the bases for future and more integrated studies.

Since the PCV13 vaccine was introduced for children <1-year-old with a 2+1 schedule and a catch-up between 12 and 24 months, a herd effect in adult population has been demonstrated in other countries7,9,11,13,15. In Argentina, despite the fact that the National Surveillance Program for adults started in 2013, we have previous retrospective data from 2010 to 2012 including serotype distribution, antibiotic resistance and vaccine serotype coverage5. Comparing this information with our findings we noticed that serotypes 1, 3, 12F and 7F still remain at the top of the most common serotypes associated with IPD in adults. However, a significant decrease in serotype 5 frequency with respect to the previous work has been observed; this fact is expected because it is included in both vaccines. In contrast, serotype 8, not included in the PCV13 vaccine, appears as the most prevalent new serotype.

This study shows that the most prevalent serotypes are 3, 8, 12F, 7F and 1. These results agree with those reported in previous studies conducted by Medeiros et al.10 and Dullius et al.4 (Brazil), Stamboulian et al.17 (Argentina, Mexico and Brazil) and Castro et al.2 (Peru). Our results are more related to those found by Stamboulian and Dullius, where we matched 8 of the first top 10 most prevalent serotypes and 7 of 10 respectively.

During the period of study there was no significant difference in serotype distribution between the two groups studied, except for serotypes 1, 3 and 23A.

Pneumonia (68%) was the most common syndrome, coinciding with the findings of the previous studies mentioned above. Meningitis ranked third in our study, in agreement with Stamboulian et al.17 and contrasting with the results shown in the studies by the other three authors, in which meningitis was the second most frequent clinical manifestation.

Serotypes 1, 3, 8 and 7F showed a significant association with meningitis. These findings are in concordance with data from Rioseco et al.14 from Chile, who reported serotypes 1, 3 and 7F among the most frequently detected; this data is also coincident with that of other authors16.

Despite being the third most prevalent serotype, we were not able to find a significant association between serotype 12F and any clinical diagnoses. This serotype is included in PSSV23 but not in PCV13 and the theoretical coverage of these vaccines is different, which could be one of the reasons for its predominance.

Serotypes included in the PCV13 and PPSV23 formulation were found in 41.34% (327/791) and 73.83% (584/791) of the infections. These numbers changed from those in the previous study conducted by Fossati et al.5, where the serotype coverage was 55.2% for PCV13 and 82.8% for PPSV23. It is important to highlight that the study conducted by Fossati et al. was performed before the introduction of PCV13 into the National Vaccination Schedule.

In our study when we combined both vaccines the value rose to 75.22% (595/791); this data reflects the theoretical coverage of these vaccines. This means that, theoretically, and depending on which vaccine the patients are receiving, they would have a reduction in the number of IPD cases associated with the serotypes identified in the present study. Mortarini et al.12 reported a theoretical coverage of PCV13 and PPSV23 of 75% and 90%, respectively, which is well above our results; however, this data was mostly obtained from HIV-positive and unvaccinated patients. Furthermore, the study was carried out only in two Hospitals whereas our work which is based on data from the National Surveillance Program shows a more diverse and more representative study population.

A decrease in the theoretical coverage of PCV13 can be observed from 2013 to 2017 in both age groups. This decrease could be related to pediatric vaccination but also to the use of the sequential scheme in adults.

In conclusion, a continuous National Surveillance Program of Spn serotypes in adults with IPD is necessary to assess future changes in the epidemiology and to make the best decisions with regard to immunization strategies.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Surveillance Network, Argentina:

Htal de Clinicas “Jose de San Martin”, Carlos Vay, Hospital General de Agudos “Donación Francisco Santojanni” Claudia Alfonso, Hospital General de Agudos “Dr. Ignacio Pirovano” Claudia Garbaz, Sanatorio Franchin Claudia Etcheves, Hospital General de Agudos “Dr. Parmenio Piñero” Daniela Ballester, Flavia Amalfa, Sanatorio Trinidad Palermo Debora Stepanik, Hospital Italiano Graciela Greco, Hospital Alemán Liliana Fernandez Caniggia, CEMIC Mariela Soledad Zarate, Hospital Británico Marta Giovanakis, Hospital General de Agudos “Dr. Carlos G. Durand” Marta Flaibani, Hospital General de Agudos “Dr. Cosme Argerich” Nora Gomez, FLENI Nora Orellana, Hospital General de Agudos “Dr. Juan A. Fernandez” Sara Kaufman, Hospital General de Agudos “Dalmacio Velez Sarsfield” Silvana Manganello, Sanatorio Guemes Soledad Zarate, HIGA Evita Ana Togneri, HIGA San Juan De Dios Andrea Pacha, HIGA “Dr. Jose Penna” Maria L Benvenutti, Mabel Rizzo, HIGA “Dr. Pedro Fiorito” Silvia Beatriz Fernandez, HIGA “Dr. Diego Paroissien” Maria R Cervelli, HIGA “Dr. Abraham F. Piñeyro” Monica Machain, HIGA “Luisa C de Gandulfo” Virginia Miraglia, Hospital Municipal de Agudos “Dr. Leonidas Lucero” Laura Paniccia, HIGA “Presidente Perón” Maria Adelaida Rosetti, HIGA“Vicente Lopez y Planes” Hebe Gullo, Maria Susana Commisso, Hospital Zonal General de Agudos “Dr. Carlos Bocalandro” Carolina Baccino, Hospital Municipal “Dr. Bernardo Houssay” Veronica Berdiñas, Hospital Universitario “Austral” Viviana Vilches, Hospital “Dr. Arturo Oñativia” Ana Laura Mariñazky, Hospital Zonal Especializado de Agudos y Crónicos “Dr. A. Cetrangolo” Appendino Andrea, Laura Biglieri, Hospital Zonal “Gdor. Domingo Mercante” Sandra Bognanni, HIGA “Eva Peron” Marisa Almuzara, Hospital Municipal “Dr. Enrique Sturiz” Alejandra Sale, Hospital Municipal “Ramón Santamarina” Monica Sparo, Hospital Municipal “Dr. Emilio Zerboni” Sofia Murzicato, Hospital Municipal “Dr. Federico Falcon” Celina Santander, Hospital Municipal “Ostaciana V. Lavignolle” Maricel Garrone, Hospital Nacional “Prof. Dr. Alejandro Posadas” Adriana Fernandez Lausi, Hospital Privado de Comunidad Monica Vallejo, Hospital Municipal “Dr. Pedro Orellana” Cecilia Barrachia, Hospital Zonal General de Agudos “Virgen del Carmen” Adriana Melo, HIGA “Dr. Enrique Erril” Victoria Ascua, Hospital Interzonal “San Juan Bautista” Viviana David, Hospital “Dr Julio C Perrando” Laura Pícoli, Mariana C. Carol Rey, Hospital 4 de Junio “Dr. Ramon Carrillo” Norma Ester Cech, Hospital Regional “Dr. Victor M. Sanguinetti” Susana Ortiz, Lab. de la direccion de patologia prevalente y epidemiologia Chubut Mario Flores, Hospital Zonal Esquel Omar Daher, Hospital “Dr. Guillermo Rawson” Ana Littvik, Hospital Regional “Dr. Louis Pasteur” Claudia Amareto De Costabella, Clinica Privada Velez Sarsfield Lidia Wolff De Jakob, Hospitasl Regional “Domingo Funes” Lilia Norma Camisassa, Clinica Universitaria “Reina Fabiola” Marina Botiglieri, Hospital “Angela Llano” Ana Maria Pato, Hospital “Delicia C. Masvernat” Maria Ofelia Moulins, Luis Otaegui, Hospital Central Formosa Nancy Noemi Pereyra, Laboratorio Central De Salud Publica Jujuy María Rosa Pizarro, Hospital “Gobernador Centeno” Adriana Pereyra, Hospital “Dr. Lucio Molas” Gladys Almada, Hospital Regional “Dr Enrique Vera Barros” Sonia Flores, Monica Romanazi, Hospital “Dr. Teodoro J Schestakow” Ada Zanusso, Adriana Edith Acosta, Hospital Publico Samic El Dorado Ana Maria Miranda, Hospital Provincial “Dr. Castro Rendon” Sandra Grenon, Hospital Escuela de Agudos “Dr. Ramón Madariaga” Viviana Villalba, Cristina Perez, Hospital “Dr. Horacio Heller” Fernanda Bulgueroni, Hospital Zonal Bariloche “Dr. Ramon Carrillo” Nestor Blazquez, Maria Laura Alvarez, Hospital Area Cipolletti Cristina Carranza, Mariela Roncallo, Hospital “Francisco Lopez Lima” Gonzalo Crombas, Hospital “Artémides Zatti” Maria Gabriela Rivolier, Hospital “Presidente Peron” Cristina Bono, Eloisa Aguirre, Hospital “San Vicente de Paul” Silvia Amador, Hospital “Marcial Quiroga” Hugo Castro, Hospital “Dr. Guillermo Rawson” Marisa Lopez, Osvaldo Navarro, Policlinico Regional “Juan Domingo Peron” Ema Maria Fernandez, Policlinico Central San Luis Hugo Rigo, Hospital Zonal de Caleta Olivia “Pedro Tardivo” Josefina Villegas, Hospital Regional de Rio Gallegos Wilma Krause, Mariel Borda, Laboratorio Central de Salud Publica Santa Fe Andrea Nepote, Maria Gilli, Hospital “Dr. Jose M. Cullen” Emilce Mendez, Alicia Nagel, CEMAR Maria Inés Zamboni, Julieta Valles, “Hospital Español” Noemi Borda, Hospital de Niños “Dr. Orlando Allasia” Stella Virgolini, Maria Rosa Baroni, Htal. Regional “Dr. Ramon Carrillo” Ana Maria Nanni De Fuster, Hospital Regional Ushuaia Manuel Boutureira, Hospital Regional Rio Grande Marcela Vargas, Hospital de Clinicas “Presidente Dr. Nicolas Avellaneda” Norma Cudmani.