Carbapenemase-producing-Serratia marcescens isolates, although infrequent, are considered important nosocomial pathogens due to their intrinsic resistance to polymyxins, which limits therapeutic options. We describe a nosocomial outbreak of SME-4-producing S. marcescens in Buenos Aires city which, in our knowledge, represents the first one in South America.

Los aislamientos de origen nosocomial de Serratia marcescens productores de carbapenemasa, si bien son infrecuentes, son considerados importantes patógenos debido a su resistencia intrínseca a las polimixinas, lo cual limita aún más las opciones terapéuticas. En este trabajo se describe un brote nosocomial causado por S. marcescens portadora de carbapenemasa de tipo SME-4 en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, el cual representaría el primero en Sudamérica.

Serratia marcescens is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for severe infections and nosocomial outbreaks. Although it does not carry acquired carbapenemase genes as frequently as other Enterobacterales such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, there are reports of KPC or MBL producing S. marcescens isolates worldwide6 and in Argentina5,11.

SME serine enzymes are chromosomally-encoded and have been exclusively reported in S. marcescens isolates. They confer resistance to carbapenems but remain susceptible to extended spectrum cephalosporins and are inhibited by classical (clavulanic acid) and new inhibitors1. To date, five SME variants (SME-1, -2, -3, -4 and -5) have been reported worldwide causing sporadic reports after their first detection in England in 19822,10,13. The first SME-4 variant was reported by the USA in Genbank under accession number KF481967; however, it has not been published yet. In South America, two clinical isolates were reported, one in Brazil in 20173 and the other when our research group reported the first case in Argentina4 in 2019. In the present study, we describe a nosocomial outbreak of SME-4 producing S. marcescens in a public hospital of Buenos Aires city, Argentina, during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

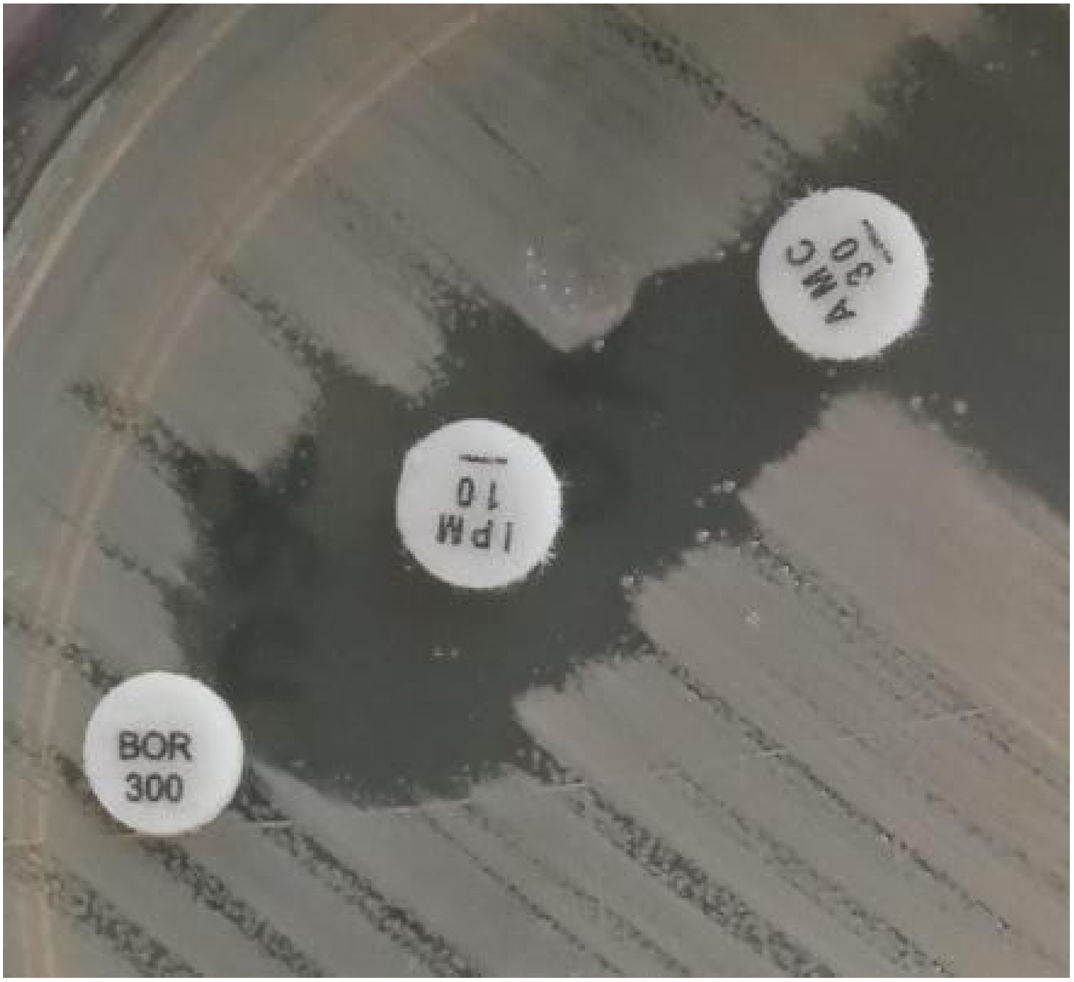

Samples belonging to four patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at Hospital Militar Central Cosme Argerich of Buenos Aires city, in June 2021 were studied. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital de Clínicas Jose de San Martin, Argentina. S. marcescens was recovered in the five isolates, of these, four (one isolate belonging to each patient) were subjected to further analysis as shown in Table 1. Identification was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and the Vitek-2 system (VITEK®2 GN) (VITEK®2 AST-N368), which was also used to perform the susceptibility testing of the isolates, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Results were interpreted following the CLSI 2021 guidelines. A confirmatory test for detection of non-KPC class A carbapenemases with amoxicillin clavulanic (AMC) acid, was performed, as well as the Blue-Carba test12 (Fig. 1).

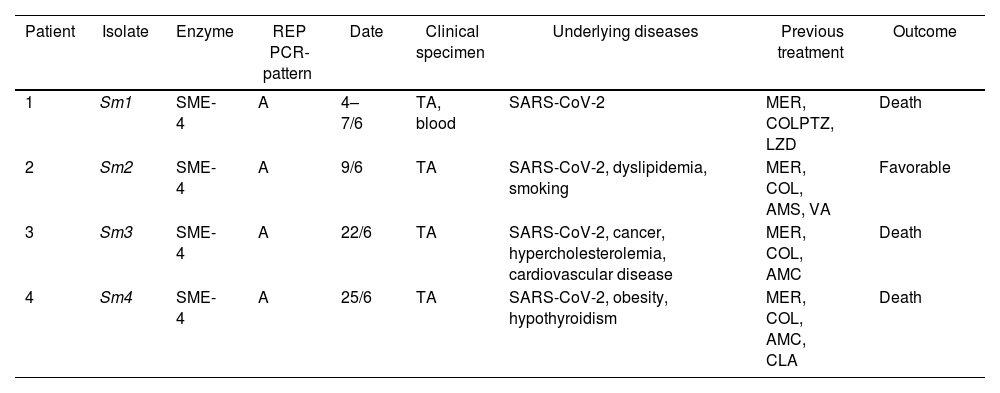

Demographic and molecular data of Serratia marcescens isolates.

| Patient | Isolate | Enzyme | REP PCR-pattern | Date | Clinical specimen | Underlying diseases | Previous treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sm1 | SME-4 | A | 4–7/6 | TA, blood | SARS-CoV-2 | MER, COLPTZ, LZD | Death |

| 2 | Sm2 | SME-4 | A | 9/6 | TA | SARS-CoV-2, dyslipidemia, smoking | MER, COL, AMS, VA | Favorable |

| 3 | Sm3 | SME-4 | A | 22/6 | TA | SARS-CoV-2, cancer, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular disease | MER, COL, AMC | Death |

| 4 | Sm4 | SME-4 | A | 25/6 | TA | SARS-CoV-2, obesity, hypothyroidism | MER, COL, AMC, CLA | Death |

TA: tracheal aspirate; AMS: ampicillin sulbactam; AMC: amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; CLA: clarithromycin; VA: vancomycin; PTZ: piperacillin–tazobactam; LZD: linezolid; MER: meropenem; COL: colistin.

Total DNA from the four isolates was extracted using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Les Ulis, France) following the manufacturer's instructions. The presence of blaSME was investigated by PCR using specific primers (SME-1A: AGGAAGACTTTGATGGGAGG and SME-1B: GGCCAAATGACGGCATAATC), which amplify an internal region of the gene, covering the 5 allelic variants described to date, followed by sequencing (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, Korea). Molecular typing was performed by REP-PCR14. A previous S. marcescens isolate harboring the SME-4 enzyme (Sm163) was included in the molecular tests as positive control4, whereas an unrelated S. marcescens isolate was included as a negative control strain (NT strain).

The four patients were admitted to the ICU with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in the same month. Demographic information about the isolates is detailed in Table 1.

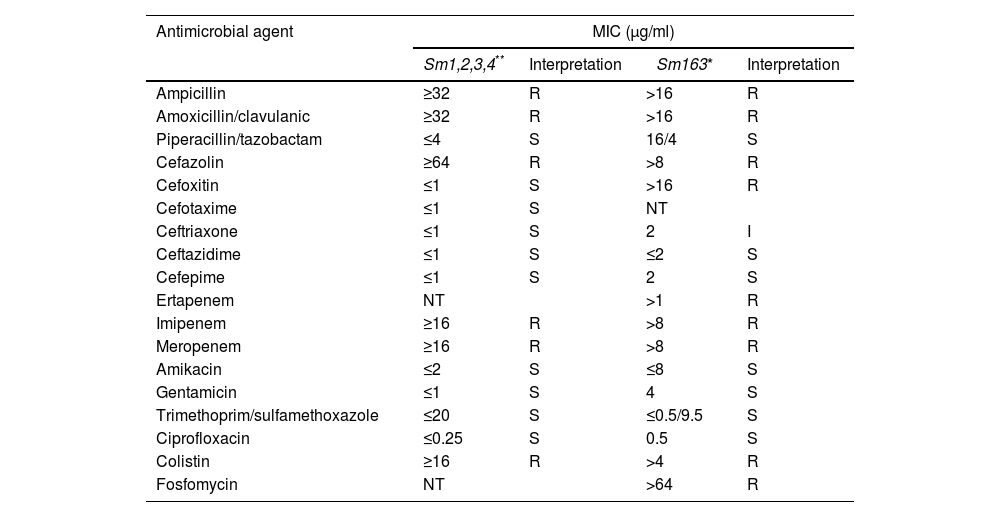

Sm1, Sm2, Sm3 and Sm4 showed the same susceptibility profile, which is detailed in Table 2. Carbapenem resistance and susceptibility to extended spectrum cephalosporins raised the alarm about a possible chromosomal class A carbapenemase that was detected phenotypically by the Blue-Carba test and the IMI-AMC-MER synergy test, which was positive in all the isolates. PCR amplification followed by sequencing of the SME gene confirmed the presence of the SME-4 variant. The four isolates displayed indistinguishable REP-PCR fingerprints (different from the NT strain pattern) confirming the suspicion of a nosocomial outbreak; the same pattern was also observed in control strain Sm163, which would suggest the possibility of a silent spread of a clone in our region.

Susceptibility profile of S. marcescens isolates.

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sm1,2,3,4** | Interpretation | Sm163* | Interpretation | |

| Ampicillin | ≥32 | R | >16 | R |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic | ≥32 | R | >16 | R |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | ≤4 | S | 16/4 | S |

| Cefazolin | ≥64 | R | >8 | R |

| Cefoxitin | ≤1 | S | >16 | R |

| Cefotaxime | ≤1 | S | NT | |

| Ceftriaxone | ≤1 | S | 2 | I |

| Ceftazidime | ≤1 | S | ≤2 | S |

| Cefepime | ≤1 | S | 2 | S |

| Ertapenem | NT | >1 | R | |

| Imipenem | ≥16 | R | >8 | R |

| Meropenem | ≥16 | R | >8 | R |

| Amikacin | ≤2 | S | ≤8 | S |

| Gentamicin | ≤1 | S | 4 | S |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | ≤20 | S | ≤0.5/9.5 | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25 | S | 0.5 | S |

| Colistin | ≥16 | R | >4 | R |

| Fosfomycin | NT | >64 | R | |

R: resistant; S: susceptible; NT: not tested.

The fact that the susceptibility profile of these isolates differs from the one observed in the most prevalent carbapenemases such as KPC or NDM makes its detection a challenge for clinical laboratories. Variability in susceptibility to meropenem and ertapenem has been described by some authors, together with the misdetection observed with some commercial phenotypic tests8. Considering that rapid molecular assays, such as the blaSME gene, are not included in the routine tests available, we should be aware of the need to perform single gene PCR testing when observing these unusual resistance profiles to avoid a possible underestimation of this resistance mechanism.

Outbreaks of S. marcescens carrying SME variants are very infrequent; except for Hopkins’ communication of seven isolates belonging to three patients in different areas of England8 and two clonally related isolates from two patients in different hospitals in Detroit7, only sporadic reports of SME-producing single isolates have been published. All SME-4 carriers reported so far have shown this enzyme to be chromosomally-encoded and the absence of S. marcescens successful clones adapted to the hospital setting may contribute to this epidemiological profile. However, the finding of these isolates should be communicated to prevent future clonal spreads. In this particular case, infection control measures to prevent the future spread of the mechanism of resistance were implemented in the Intensive Care Unit; they included isolation in separate rooms, surveillance cultures and antimicrobial therapy.

The first S. marcescens isolates carrying SME-4 in our country were recovered from both a surveillance rectal swab and a catheter blood culture from a patient attended at the University hospital of Buenos Aires city in the year 2016. The molecular studies performed on that isolate showed that the blaSME-4 gene was located on a SmarGI1-1-like genomic island that may contribute to the mobilization of this gene among different S. marcescens isolates4,9. No epidemiological link was found between the outbreak described in the present study and the previous clinical finding. Furthermore, it is of note that during these five years there had not been any reports of S. marcescens isolates with a similar phenotypic and genotypic profile in Argentina.

In the present work we describe the first nosocomial outbreak of four SME-4 producing S. marcescens isolates belonging to four patients in South America, which also represents the most extensive outbreak worldwide. We emphasize the need to be aware of the detection of these infrequent isolates to prevent the silent spread of this resistance mechanism in this nosocomial pathogen which represents a concern for clinicians due to the limited therapeutic options available.

Ethical approvalThis work was carried out with bacterial isolates of clinical origin. All procedures performed in the study met the ethical standards of Hospital de Clinicas Jose de San Martin, B.A, Argentina (project UBACyT 20020130100167BA to Angela Famiglietti) and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and further amendments.

FundingThis work was supported by UBACyT20020130100167BA to Angela Famiglietti.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.