Norovirus (NoV) is the leading cause of outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis worldwide. These are non-enveloped viruses that are classified into 10 genogroups, of which genogroup I (GI), II (GII), IV (GIV), VIII (GVIII), and IX (GIX) are the ones that infect humans. Two outbreaks (A and B) of acute gastroenteritis that occurred in a nursery school are described. The first outbreak (A) occurred in November 2018, and the second (B) in February 2020. The detection of viral and bacterial pathogens was performed to study both outbreaks. Additionally, an epidemiological investigation of the outbreaks was conducted. In the analyzed fecal and vomit samples from both children and adults in the nursery school, NoV GII.4 [P16] Sydney 2012 and NoV GI.3 [P13] were detected in outbreaks A and B, respectively. Since the study of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks is underestimated in Argentina, it is necessary to design prevention, study, and control protocols, as well as to improve the outbreak notification system in our country.

Norovirus (NoV) es la principal causa de brotes de gastroenteritis aguda en todo el mundo. Estos son virus no envueltos y se clasifican en diez genogrupos; los genogrupos I (GI), II (GII), IV (GIV), VIII (GVIII) y IX (GIX) son los que infectan a humanos. Se describen dos brotes (A y B) de gastroenteritis aguda ocurridos en un jardín maternal. El primer brote (A) ocurrió en noviembre de 2018, y el segundo (B), en febrero de 2020. Para el estudio de ambos brotes se realizó la detección de patógenos virales y bacterianos. Además, se llevó a cabo una investigación epidemiológica de los brotes. En las muestras de materia fecal y vómito analizadas, tanto de niños como de adultos del jardín maternal, se detectó NoV GII.4 [P16] Sydney 2012 en el brote A y NoV GI.3 [P13] en el brote B. Debido a que el estudio de brotes de gastroenteritis aguda es subestimado en Argentina, es necesario diseñar protocolos de prevención, estudio y control de esta afección, así como también mejorar el sistema de notificación de brotes en nuestro país.

Norovirus (NoV) is the most common cause of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) outbreaks worldwide16. It is classified into 10 genogroups, of which genogroups I (GI), II (GII), IV (GIV), VIII (GVIII), and IX (GIX) have the capacity to infect humans. Genogroups are further subdivided into 48 genotypes based on the amino acid sequence of the major capsid protein (VP1)1,5. NoV is characterized by a low infective dose and a high level of transmissibility. Typical symptoms include nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhea, fever and general malaise. The incubation period for AGE range between 12 and 48h. Severe dehydration, a common complication, often requires hospitalization and intravenous rehydration22. AGE affects individuals of all ages, with a higher disease burden observed among children, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients3,4. Genogroup II is responsible for over 75% of NoV outbreaks worldwide, with a predilection for semi-closed settings, such as schools, homes, nursing homes, cruise ships, kindergartens, and nursery schools. NoV exhibits the capacity to remain infectious in various environments, including refrigerated foods, raw vegetables, fruits, and surfaces and utensils in contact with food. Moreover, the foodborne transmission of NoV is associated with infections in food handlers17. Due to these factors, NoV is one of the primary viruses linked to foodborne illnesses13,17. Other transmission mechanisms for NoV include contaminated water and person-to-person contact, involving the ingestion of viral particles or nasal absorption due to the aerosolization of vomit19.

The aim of this study is to describe two outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis caused by two different strains of norovirus. These outbreaks affected both children and adults in the same nursery school setting.

Materials and methodsSetting descriptionThe nursery school is situated in the city of Buenos Aires. Children aged between 3 months and 4 years old attend the school, and are organized into five distinct classrooms, namely Classroom 1 through Classroom 5, based on their respective age groups. The nursery school is located in an urban area characterized by average economic resources and has separate facilities for children and adults, including separate bathrooms. Additionally, the school is equipped with essential amenities including access to potable water and sewage facilities.

The nursing school operates from 9:00 am to 4:00 pm. Food provisions are managed through a contracted catering company, which delivers pre-cooked and individually packaged meals for each classroom. The responsibility for serving these meals to the children falls on the respective classroom teachers. The menu selection is made according to the children's age group and includes a diverse range of options, such as cooked or raw vegetables in salads, red meat, chicken, as well as fruit and dairy desserts. Notably, ground meat dishes are omitted from the menu. For infants aged between 6 months and 1 year, a separate diet is administered, excluding certain foods like red meat, eggs, and specific vegetables. It is important to highlight that the children's menu is exclusively consumed by the infants and is not intended for the staff.

Epidemiological investigationOutbreak AIn November 2018, seven one-year-old children and a teacher exhibited symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. Furthermore, two of these cases required hospitalization due to severe dehydration. Fortunately, both hospitalized cases resolved favorably and no fatalities were reported as a consequence of the outbreak. All cases were associated to Classroom 3.

Outbreak BIn February 2020, a total of 20 people from the same nursery school showed symptoms of vomiting and diarrhea. Of those, 10 adults from the staff and 10 children from Classroom 1 (3 months–6 months old) and Classroom 2 (6 months–1 year old) were affected.

To investigate both outbreaks, an epidemiological survey was conducted among the cases, their contacts, and the nursery school staff. The survey solicited information from parents and staff regarding symptoms, onset dates, symptom durations, potential contact with individuals exhibiting gastrointestinal symptoms, and suspected food ingestion for the current day and the previous two days. A case–control study was conducted to determine the possible cause of the outbreak. Stool and vomit samples were collected from the affected individuals and sent to INEI-ANLIS Dr. Carlos G. Malbrán for thorough viral and bacterial testing.

In Outbreak A, a total of five stool samples and one vomit sample were collected. Two of these stool samples came from two individuals, one stool sample and one vomit sample came from one individual and the other two stool samples from two contacts. In Outbreak B, a total of 20 stool samples were collected, each corresponding to an individual case.

Sample processingIn this study, we conducted an analysis using human clinical samples collected for the referential diagnosis of enteropathogens during an epidemic outbreak. The analysis focused solely on age and classroom variables to maintain the confidentiality of personal data. The development of this study posed no risks to patients or the environment as prior informed consent was deemed unnecessary12. Consistent referential procedures for viral and bacterial diagnoses were applied uniformly across all samples from both outbreaks. Viral investigation was achieved in the Viral Gastroenteritis Laboratory of INEI-ANLIS Dr. Carlos G. Malbrán. The samples were stored at 4°C until processing. Each sample underwent a preparatory step, involving the preparation of a 10% suspension using PBS buffer, followed by centrifugation at 5000RPM. Nucleic acid extraction was conducted using a commercial method (Easy Pure Viral DNA/RNA Kit Trans™, Transgenbiotech). Detection of NoV GI and GII, Sapovirus (SV), Astrovirus (AsV), and Group F Adenovirus (AdV) detection was achieved through real-time RT-PCR techniques, as described previously6,15,21.

In addition, Group A Rotavirus testing (RVA) was performed using a nanobody-based enzyme immunoassay24. Intoxication was suspected due to the acute onset of symptoms; therefore, the samples were referred to the bacteriology department of INEI-ANLIS Dr. Carlos G. Malbrán for an investigation into enterotoxin-producing bacteria responsible for acute gastroenteritis. The presence of Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus was confirmed by bacterial culture.

Genotyping proceduresNorovirus-positive samples were genotyped through amplification and sequencing of a partial region from the ORF1/ORF2 overlap, following a previously described methodology9. Genotype assignments were accomplished using the online software Human Calicivirus Typing Tool (https://norovirus.ng.philab.cdc.gov)23. The norovirus sequences from each outbreak were submitted to GenBank with the accession numbers OP161251–161252 (Outbreak A) and OP156603–156604 (Outbreak B).

ResultsOutbreak AAmong the eight primary cases identified, a total of five stool samples and one vomit sample were examined. Four of these samples originated from three children associated with Classroom 3, with one child contributing both stool and vomit samples. Additionally, two supplementary samples were obtained from the mothers of two affected children. Unfortunately, no samples could be obtained from the remaining cases. Upon analysis of all the samples, only the presence of Norovirus Genogroup II (NoV GII) was detected. Statistical analysis was performed by Infostat software11. No bacterial pathogens were identified in either the stool or vomit samples.

Epidemiological analysisA total of 44 surveys were completed, with 30 (68.2%) from children and their families and 14 (31.8%) from teachers and administrative staff at the nursery school. Upon analysis, the surveys revealed that eight individuals associated with the nursing school were affected, comprising seven children and one teacher. Additionally, 24 cohabiting and non-cohabiting relatives reported gastrointestinal symptoms. Importantly, all of these contacts were confined to children in Classroom 3. Noteworthy, findings from the survey include the observation that the same menu was served in classrooms 3 through 5 of the nursery school. However, only children attending Classroom 3 and one teacher working there exhibited illness. Only four parents of these affected children reported suspecting that their child had consumed raw food the previous day at the nursery school, specifically a salad containing tomatoes and broccoli.

The most prevalent symptoms reported among the affected individuals included vomiting (53.0%), diarrhea (53.0%), nausea (15.6%), fever (9.3%), and dehydration (6.2%) (Table 1). Notably, 33/44 (75%) respondents did not report any symptoms or previous contact with individuals experiencing gastroenteritis. Fig. 1 illustrates an epidemic curve displaying three distinct peaks of infection transmission. The initial peak corresponds to primary cases indicating a common point source of origin. The subsequent two peaks correspond to secondary cases resulting from person-to-person contact. To further investigate potential risk factors, a case–control study was conducted. The analysis revealed that being in Classroom 3 significantly increased the risk of illness (OR=29.0, p=0.0002). The incubation period for the illness was estimated to be approximately 36–48h (Fig. 1). Consequently, the nursery school was temporarily closed for 24h and comprehensive cleaning measures were implemented to control the outbreak. Two positive samples with high viral load were genotyped, both belonging to GII.4 [P16] Sydney 2012.

Summary of clinical features and results of the study of both outbreaks. Cases confirmed by laboratory analyses and cases surveyed are considered.

| Outbreak | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Total cases | 32 | – | 26 | – |

| Primary cases | 8 | – | 20 | – |

| Secondary cases | 24 | – | 6 | – |

| Hospitalized cases | 2 | – | – | – |

| Total stool samples | 5 | – | 20 | – |

| Total vomit samples | 1 | – | – | – |

| NoV samples detected | 6/6 | 100 | 12/20 | 60 |

| Watery diarrhea | 16/32 | 53 | 18/26 | 69 |

| Nausea | 6/32 | 15.6 | – | – |

| Vomiting | 16/32 | 53 | 15/26 | 57 |

| Fever | 3/32 | 9.3 | – | – |

| Severe dehydration | 2/32 | 6.2 | – | – |

| Genotype | GII.4 [P16] | GI.3 [P13] | ||

Outbreak A epidemic curve. This figure illustrates an epidemic curve delineating distinct peaks; the initial peak corresponds to primary cases with a shared source of infection, whereas the subsequent peaks denote secondary cases arising from person-to-person transmission. The cases confirmed by laboratory analysis and the cases surveyed were considered.

A total of 20 stool samples obtained from both affected children and nursery school staff were studied. The results indicated a positive outcome for NoV GI in 12/20 (60%) samples. Notably, seven of the positive samples (7/12) pertained to the nursery school staff, including teachers, administrative personnel, kitchen staff, and the nursery school manager. The remaining five positive samples (5/12) were attributed to children aged between 9 and 15 months. No bacterial pathogens were identified in any of the stool samples.

Epidemiological analysisA limited number of 10 surveys was completed, seven of which belonged to children under 1 year old and the remaining three were completed by nursery school staff (two teachers and an administrative staff member). The symptomatic children were observed to fall into two different groups: those less than 6 months and those aged between 6 and 12 months. Importantly, these symptomatic children attended separate classrooms. Furthermore, an additional six symptomatic cases were documented among relatives residing with two of the affected children. Notably, none of the participants expressed concerns about the food provided in the nursery school's menu. However, one staff member reported being in contact with another staff member who had previously experienced gastrointestinal symptoms.

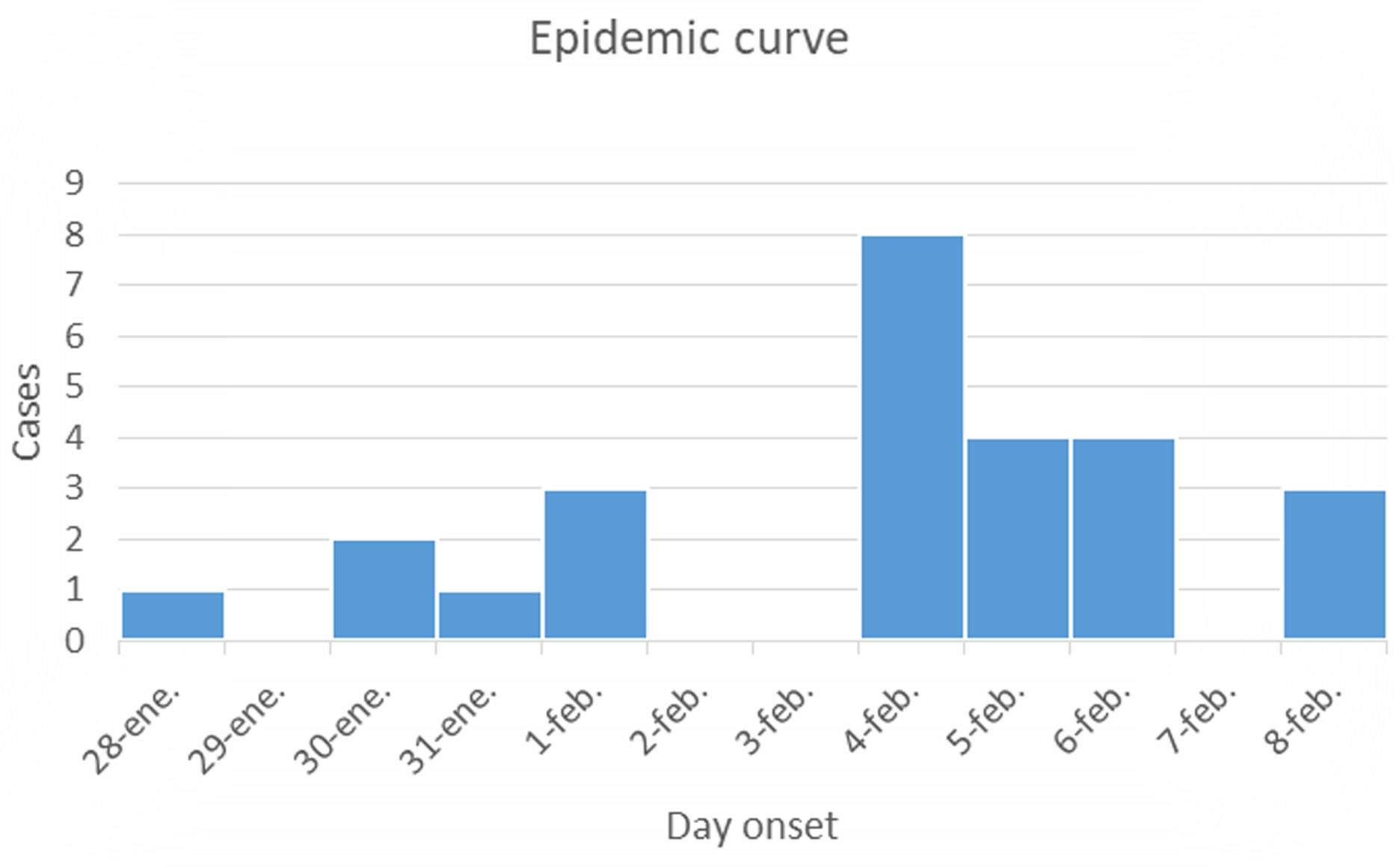

Fig. 2 illustrates an epidemic curve that exhibits a series of peaks, each of them separated by an incubation period estimated to be approximately of 48h. These successive peaks involve an increased number of cases until control measures were implemented. It illustrated primary cases (children) as the first peak and secondary cases (relatives and visitors) as the second and third peaks. Both laboratory-confirmed cases and surveyed cases were considered in this analysis. The most prevalent symptoms reported among the affected individuals were diarrhea (69%) and vomiting (57%), as outlined in Table 1. The observed incubation period was approximately 48h, aligning with the periodicity of the successive peaks in the epidemic curve (Fig. 2).

Outbreak B epidemic curve. This figure illustrates an epidemic curve characterized by a series of prominent peaks, each separated by a single incubation period of 48h. This pattern suggests the propagation of the contagion, potentially through person-to-person contact. The cases confirmed by laboratory analysis and the cases surveyed are considered.

Despite these observations, the case–control study found no significant association between the food consumed at the nursery school and the risk of illness (OR=2.2, p=0.5210). In response to these findings and to reduce the transmission of norovirus (NoV), the nursery was temporarily closed and subjected to thorough cleaning measures. Two positive samples with high viral load were genotyped, both belonging to GI.3 [P13].

DiscussionThis study delineates two distinct outbreaks within the same nursing school. Outbreak A is postulated to have originated from a single source exclusively present in Classroom 3, as evidenced by a significant correlation between the fact of being in that specific classroom and falling ill. The potential sources of contamination include either food handled within the classroom or contact with a contaminated surface. Secondary cases in Outbreak A are likely to have resulted from person-to-person transmission, with affected children serving as the primary sources. The observed pattern in the epidemic curve strongly indicates a common source of infection that is subsequently propagated through person-to-person contact. This characteristic curve, with a series of peaks one incubation period apart, points towards a scenario where an initial source of contagion likely affected a group, and the subsequent peaks signify the transmission of the infection among individuals. Airborne transmission, facilitated by the aerosolization of vomit, is proposed as a plausible mechanism contributing to the extended transmission dynamics18. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for implementing effective control measures and preventive strategies in similar settings.

Identification of the Sydney variant of NoV GII.4 [P16] genotype in the current study is noteworthy, as this variant has been previously associated with distinct characteristics. Reports suggest that the Sydney variant is linked to longer symptom duration, an increased likelihood of hospitalization and death, and a higher potential for causing epidemics2,10,14. Furthermore, it is highlighted as the most prevalent strain of NoV currently circulating in Argentina. Notably, this particular variant has been detected not only in human populations but also in oyster populations within the country, underscoring its widespread presence and potential implications for both public health and environmental considerations8,20.

Unfortunately, the information available for Outbreak B is limited, with only a few surveys completed. Nevertheless, the investigation conducted reveals a significant finding: one of the teachers involved had contact with a sick staff member two days before the outbreak and subsequently tested positive for NoV GI. The initial manifestation of symptoms occurred in the teacher while present at the nursery school. Subsequently, children and another staff member fell ill after close contact with the affected teacher.

From the available data, it can be inferred that the outbreak primarily affected the staff members, with subsequent transmission to the children occurring through direct contact. Regrettably, information regarding the source of the primary infection could not be determined.

The epidemic curve for Outbreak B reveals a series of peaks occurring at intervals of one incubation period (48h). These peaks imply an increase in the number of cases until control measures were implemented, indicating the potential propagation of the source of contagion. Person-to-person contact is implicated as a likely mode of transmission. The identified strain of NoV GI in this outbreak was GI.3 [P13]. Notably, this specific capsid and polymerase association had not been previously detected in Argentina. It diverges from the patterns observed in the two reported NoV GI outbreaks in Argentina in 2013 and 2017, both identified with the GI.6 [P11] genotype8. Moreover, in 2016, the capsid genotype GI.3 was detected in Argentina, but it was only associated with polymerase genotype GI.[P3], linked to a sporadic case of gastroenteritis. This emphasizes the uniqueness of the GI.3 [P13] strain identified in Outbreak B, underscoring the dynamic nature of norovirus genotypes circulating in the region.

This study is the first report of GI.3 [P13] genotype circulation in our country. Previous reports have only detected this genotype among children in Taiwan between 2015 and 2019, which resulted in acute gastroenteritis outbreaks associated with suspected waterborne transmission7,25. To control the transmission and prevent further cases, the nursing school implemented temporary closure for 48h, coupled with thorough cleaning measures. The effectiveness of these measures is evident as no additional cases were identified in either outbreak after the reopening. Furthermore, training initiatives were undertaken for nursing school staff, focusing on effective food handling methods, NoV infection prevention (including surface disinfection with bleach), and the importance of frequent handwashing1. However, the study has several limitations. The limited number of completed surveys, especially in Outbreak B, introduces potential bias. Despite mandatory reporting of foodborne outbreaks in Argentina, underreporting and insufficient epidemiological information remains an issue. Delays in studying viral pathogens and the self-limiting nature of gastroenteritis, leading to a lack of medical attention, further contribute to underreporting. This study emphasizes the need to enhance public awareness, particularly among those in semi-enclosed settings, regarding preventive measures and appropriate response protocols for foodborne illness outbreaks. Addressing underreporting and resource limitations in health centers for accurate NoV diagnosis is crucial. The establishment of comprehensive prevention, research, and control protocols is imperative to enhance our country's outbreak notification system.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors state that no human or animal experiments have been performed for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThe present research has not received any specific grants from agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

We thank Marina Mozgovoj for critical reading of the manuscript.