Delays resulting from the transfer to perform primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have a negative impact on the benefits of the procedure.

MethodsProspective registry aimed at comparing the results of primary PCI in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) admitted or transferred to an interventional cath lab equipped hospital.

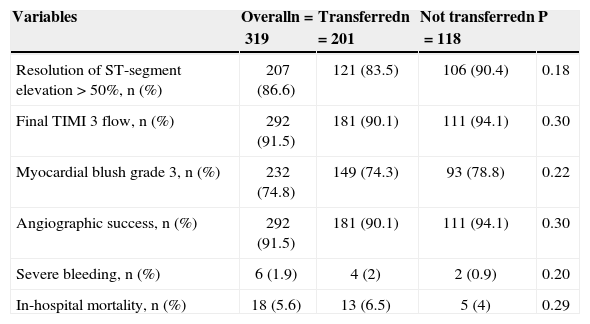

ResultsBetween February 2009 and December 2011, 319 patients were included in the study with mean age of 59.8±12 years, 28.5% were female and 22.3% were diabetics. Patients transferred for primary PCI (n=201) had longer door-to-balloon time (86.4±26.6min vs 69±22.6min; P<0.0001), a non-significant decrease in ST-segment elevation resolution (83.5% vs 90.4%; P=0.18), final TIMI 3 flow (90.1% vs 94.1%; P=0.30), myocardial blush grade 3 (74.3% vs 78.8%; P=0.22) and angiographic success (90.1% vs 94.1%; P=0.30), and a non-significant increase in major bleeding (2% vs 0.9%; P=0.20) and hospital mortality (6.5% vs 4%; P=0.29).

ConclusionsThe referral of patients with STEMI directly to an interventional cath lab equiped hospital is associated with shorter door-to-balloon time and non-significant improvement of reperfusion markers and mortality.

Impacto da Transferência Inter-hospitalar nos Resultados daIntervenção Coronária Percutânea Primária

IntroduçãoAtrasos decorrentes da transferência para realização de intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) primária impactam negativamente os benefícios do procedimento.

MétodosRegistro prospectivo objetivando comparar os resultados da ICP primária entre pacientes com infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST (IAMCSST) admitidos ou transferidos para hospital equipado com laboratório de intervenção.

ResultadosEntre fevereiro de 2009 e dezembro de 2011, foram incluídos 319 pacientes, com média de idade de 59,8±12 anos, 28,5% do sexo feminino e 22,3% diabéticos. Pacientes transferidos para realização de ICP primária (n=201) apresentaram tempo porta-balão mais longo (86,4±26,6min vs. 69±22,6min; P<0,0001), diminuição não significativa da resolução do supradesnivelamento do segmento ST (83,5% vs. 90,4%; P=0,18), do fluxo final TIMI 3 (90,1% vs. 94,1%; P=0,30), do blush miocárdico grau 3 (74,3% vs. 78,8%; P=0,22) e do sucesso angiográfico (90,1% vs. 94,1%; P=0,30), e incremento não significativa de sangramento grave (2% vs. 0,9%; P=0,20) e mortalidade hospitalar (6,5% vs. 4%; P=0,29).

ConclusõesO encaminhamento do paciente com IAMCSST diretamente a hospital com laboratório de intervenção associa-se a menor tempo portabalão e melhora não significativa dos marcadores de reperfusão e da mortalidade.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy for acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), provided that it is performed within the first 90 minutes after the diagnosis by experienced staff at a high-volume center.1 Until 2006, statistics from the United States showed that approximately 25% of hospitals had no access to primary PCI and that only 10% of patients were treated within the optimal time range suggested by the guidelines.2 Updated data have reported an improved mean door-to-balloon time of 64.5minutes, increasing to 121 minutes in transferred patients.3 In Brazil, preliminary results from the Clinical Practice Registry for Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACCEPT), which represents 47 national referral institutions, have observed a mean 125-minute delay between the diagnosis and the completion of the procedure; only 36% of cases were effectively treated in less than 90 minutes.4

Strategies aimed at reducing the delay when performing primary PCI are a topic of current and increasing interest. A meta-regression analysis of 5,741 patients in 11 randomized trials demonstrated the superiority of transferring patients to undergo primary PCI compared with performing local fibrinolysis in reducing mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke.5 However, these findings are applicable to the patients included in these studies, which were characterized by reduced door-to-balloon times, and thus not applicable to the real world, in which delays arising from patient transfers are commonly observed. In this scenario, the benefits determined by mechanical reperfusion can be attenuated or lost completely.

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of inter-hospital transfer on the efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI in the city of Marília, SP, Brazil, which offers an integrated and efficient care system for cardiovascular emergencies.

METHODSThe present study analyzed a prospective registry of consecutive patients diagnosed with STEMI who underwent primary PCI (within 12 hours of evolution) in Marília, SP, Brazil. With an estimated population of 226,000 inhabitants (based on the most recent census of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE]), the city has 12 basic health units (BHU) and two emergency hospitals (EH) that belong to the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS) network. Two tertiary hospitals, one of which is equipped with an interventional cardiology lab that operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with an annual volume of over 500 annual PCI procedures, constituted the reference point for treating cardiovascular emergencies. Transportation between the basic units and the tertiary hospitals, as well as inter-hospital transportation (distance of approximately 2km), are performed by the Emergency Mobile Care Service (Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência – SAMU). Patients with a pre-hospital diagnosis of STEMI are taken directly to the interventional laboratory, after telephone contact with the staff in charge, thus preventing delays arising from the necessity to go through the emergency department.

Patients who were transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention were compared to those who were admitted directly to a hospital capable of performing the procedure. The evaluated efficacy outcomes included the angiographic success rate, restoration of epicardial Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 3 flow, myocardial blush grade 3, resolution of ST-segment elevation>50%, and in-hospital mortality. The safety outcome consisted of severe bleeding. In accordance with the classification of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium,6 severe bleeding was defined according to the following categories: type 3 ([3a] bleeding with a decrease in haemoglobin≥3 and<5g/dL or a transfusion of packed red blood cells; [3b] bleeding with a decrease in haemoglobin≥5g/ dL, cardiac tamponade, bleeding requiring surgical intervention, or bleeding requiring intravenous vasoactive drugs; [3c] intracranial haemorrhage, as confirmed by autopsy or subcategories, imaging examinations or lumbar puncture, or intraocular bleeding with vision impairment); or type 5 ([5a] probable fatal bleeding, [5b] definite fatal bleeding). Transportation time was defined as the interval between the electrocardiogram (EKG) diagnosis and the patient’s arrival at the interventional laboratory. Symptom-to-balloon time was defined as the interval between symptom onset and the crossing of the lesion with pre-dilatation balloon, manual aspiration catheter, or stent. Door-to-balloon time was defined as the interval between the EKG diagnosis and crossing the lesion with pre-dilatation balloon, manual aspiration catheter, or stent.

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software, release 12.0 (SPSS Inc. – Chicago, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and their percentages and were compared with the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations and were compared using Student’s t-test. Statistically significant results were determined with a P-value<0.05.

RESULTSBetween February 2009 and December 2011, 319 patients who were diagnosed with STEMI and underwent primary PCI were included in the study, 118 of whom were directly admitted to a tertiary hospital equipped with an interventional cardiology laboratory; 201 patients were initially treated at tertiary hospitals lacking these facilities, and were later transferred to another hospital to undergo the procedure.

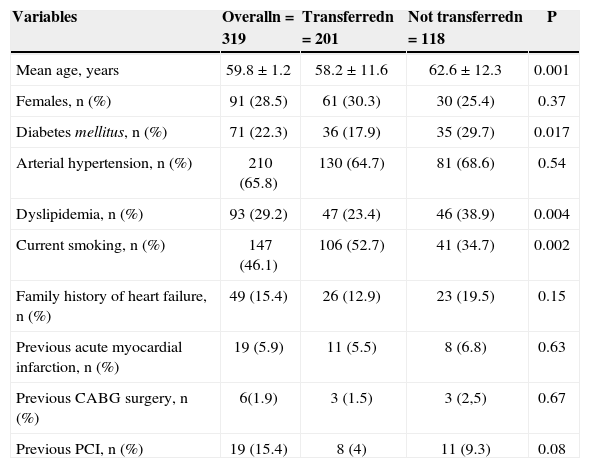

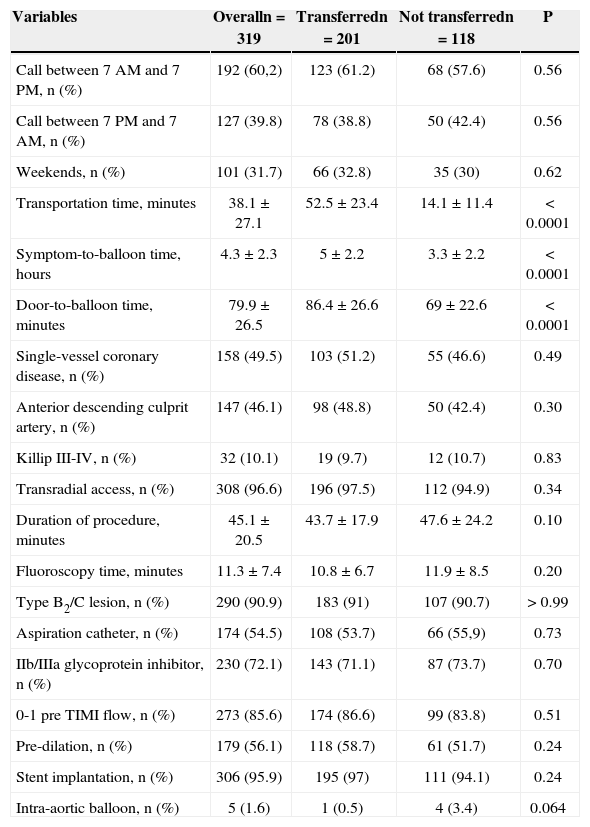

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The subjects’ mean age was 59.8±12 years; 71.5% were males, and 22.3% had diabetes mellitus. The characteristics of the procedures were similar between groups, except for higher transportation time (52.5 ± 23.4minutes vs. 14.1 ± 11.4minutes; P<0.0001), longer symptom-to-balloon time (5 ± 2.2hours vs. 3.3 ± 2.2hours; P<0.0001), and higher door-to-balloon time (86.4 ± 26.6minutes vs. 69 ± 22.6minutes; P<0.0001) in the transferred patients (Table 2).

Basal clinical and demographic characteristics

| Variables | Overalln=319 | Transferredn=201 | Not transferredn=118 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 59.8±1.2 | 58.2±11.6 | 62.6±12.3 | 0.001 |

| Females, n (%) | 91 (28.5) | 61 (30.3) | 30 (25.4) | 0.37 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 71 (22.3) | 36 (17.9) | 35 (29.7) | 0.017 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 210 (65.8) | 130 (64.7) | 81 (68.6) | 0.54 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 93 (29.2) | 47 (23.4) | 46 (38.9) | 0.004 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 147 (46.1) | 106 (52.7) | 41 (34.7) | 0.002 |

| Family history of heart failure, n (%) | 49 (15.4) | 26 (12.9) | 23 (19.5) | 0.15 |

| Previous acute myocardial infarction, n (%) | 19 (5.9) | 11 (5.5) | 8 (6.8) | 0.63 |

| Previous CABG surgery, n (%) | 6(1.9) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (2,5) | 0.67 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 19 (15.4) | 8 (4) | 11 (9.3) | 0.08 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Procedural characteristics

| Variables | Overalln=319 | Transferredn=201 | Not transferredn=118 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Call between 7AM and 7PM, n (%) | 192 (60,2) | 123 (61.2) | 68 (57.6) | 0.56 |

| Call between 7PM and 7AM, n (%) | 127 (39.8) | 78 (38.8) | 50 (42.4) | 0.56 |

| Weekends, n (%) | 101 (31.7) | 66 (32.8) | 35 (30) | 0.62 |

| Transportation time, minutes | 38.1±27.1 | 52.5±23.4 | 14.1±11.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Symptom-to-balloon time, hours | 4.3±2.3 | 5±2.2 | 3.3±2.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Door-to-balloon time, minutes | 79.9±26.5 | 86.4±26.6 | 69±22.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Single-vessel coronary disease, n (%) | 158 (49.5) | 103 (51.2) | 55 (46.6) | 0.49 |

| Anterior descending culprit artery, n (%) | 147 (46.1) | 98 (48.8) | 50 (42.4) | 0.30 |

| Killip III-IV, n (%) | 32 (10.1) | 19 (9.7) | 12 (10.7) | 0.83 |

| Transradial access, n (%) | 308 (96.6) | 196 (97.5) | 112 (94.9) | 0.34 |

| Duration of procedure, minutes | 45.1±20.5 | 43.7±17.9 | 47.6±24.2 | 0.10 |

| Fluoroscopy time, minutes | 11.3±7.4 | 10.8±6.7 | 11.9±8.5 | 0.20 |

| Type B2/C lesion, n (%) | 290 (90.9) | 183 (91) | 107 (90.7) | > 0.99 |

| Aspiration catheter, n (%) | 174 (54.5) | 108 (53.7) | 66 (55,9) | 0.73 |

| IIb/IIIa glycoprotein inhibitor, n (%) | 230 (72.1) | 143 (71.1) | 87 (73.7) | 0.70 |

| 0-1 pre TIMI flow, n (%) | 273 (85.6) | 174 (86.6) | 99 (83.8) | 0.51 |

| Pre-dilation, n (%) | 179 (56.1) | 118 (58.7) | 61 (51.7) | 0.24 |

| Stent implantation, n (%) | 306 (95.9) | 195 (97) | 111 (94.1) | 0.24 |

| Intra-aortic balloon, n (%) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (3.4) | 0.064 |

The predominant arterial access route was the transradial approach (96.6%), whereas the femoral approach was used in nine cases (2.8%), and the ulnar approach in two cases (0.6%). The failure rate of the transradial approach was 0.97% (three cases), due to chronic occlusion of the innominate artery, severe tortuosity of the radial artery, and lack of support for the PCI performance. In 99% of the procedures, 6F introducers were used; stents were implanted in 95.9% of cases.

The patients who were transferred for primary PCI had lower rates of resolution of ST-segment elevation, final TIMI 3 flow, myocardial blush grade 3, and angiographic success, with a non-significant increase of severe bleeding and in-hospital mortality (Table 3).

Efficacy and safety outcomes

| Variables | Overalln=319 | Transferredn=201 | Not transferredn=118 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution of ST-segment elevation>50%, n (%) | 207 (86.6) | 121 (83.5) | 106 (90.4) | 0.18 |

| Final TIMI 3 flow, n (%) | 292 (91.5) | 181 (90.1) | 111 (94.1) | 0.30 |

| Myocardial blush grade 3, n (%) | 232 (74.8) | 149 (74.3) | 93 (78.8) | 0.22 |

| Angiographic success, n (%) | 292 (91.5) | 181 (90.1) | 111 (94.1) | 0.30 |

| Severe bleeding, n (%) | 6 (1.9) | 4 (2) | 2 (0.9) | 0.20 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 18 (5.6) | 13 (6.5) | 5 (4) | 0.29 |

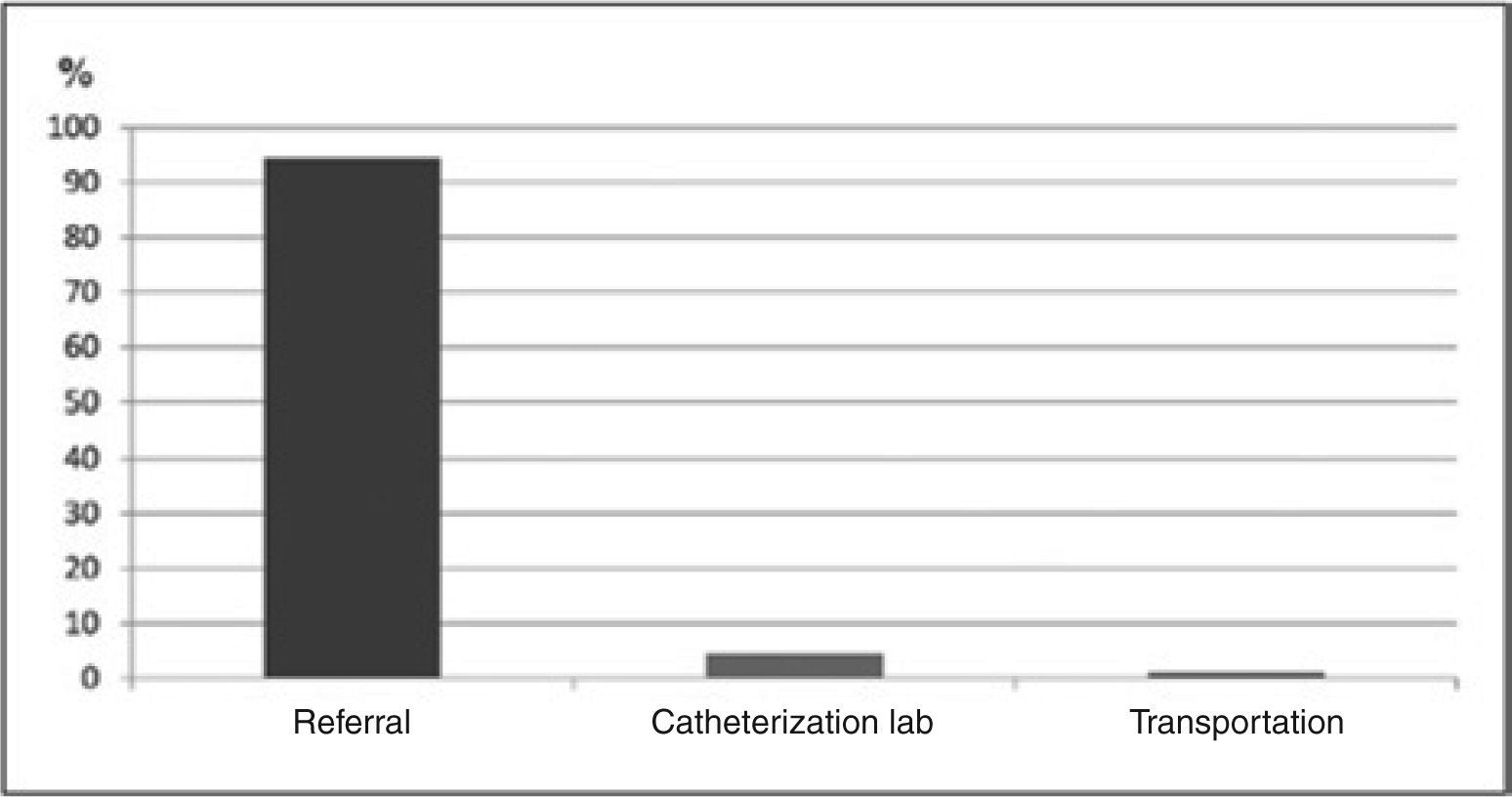

The main determinants of inter-hospital transfer delay include the delays related to patient referral (e.g., authorization by the Hospital Bed Regulatory System and SAMU availability) in 190 cases (94.5%), factors related to the intervention center (e.g., availability of a multidisciplinary team and simultaneous use of the unit for another procedure) in nine cases (4.5%), and delays in inter-hospital transportation in two cases (1%) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSIONThe study results demonstrate that the organization and use of an integrated care system for patients with STEMI, even among those patients transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention, achieve a door-to-balloon time within the range recommended by the guidelines. However, the present findings should be interpreted with caution. The choice of strategy for inter-hospital transfers necessarily promotes an increase in transportation time, symptom-to-balloon time, and door-to-balloon time, to the detriment of local fibrinolysis.7 In Marília, the inter-hospital distance is only 2km, and the city does not have the difficulties that are inherent to the urban traffic of metropolitan regions. In addition, although not statistically significant, the transferred patients had lower resolution rates of S-T segment elevation, final TIMI 3 flow, myocardial blush grade 3, and angiographic success, with increased rates of severe bleeding and in-hospital mortality.

In fact, data from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI) show that the benefit of transfers for primary PCI compared to fibrinolysis is time-dependent. Mortality rates alone, mortality/reinfarction rates, and mortality/reinfarction/stroke rates are lower and more favourable compared to primary PCI when the delay to the start of treatment is less than 60 minutes or 60-90 minutes; the benefit becomes questionable when this time exceeds 90 minutes and is absent after 120 minutes.8 Thus, it becomes imperative to develop strategies that facilitate access to primary PCI and reduce the door-to-balloon time. The most common attributable causes of delay for inter-hospital transfer are those related to referral (e.g., waiting for transportation; unclear or non-diagnostic EKG), followed by delays in the intervention center (e.g., staff availability and procedure complexity) and the transportation of patients (e.g., distances, weather and geographical features).9 In the present study, the major factors were waiting for the transportation and bureaucratic transfer regulations.

The direct transportation of patients with a pre-hospital diagnosis of STEMI to the interventional cardiology lab, preceded by contact and team awareness, is a simple measure that is capable of increasing by three-fold the proportion of patients treated within the recommended therapeutic window, which results in higher rates of final TIMI 3 flow; this outcome, in turn, is an important predictor of long-term survival.10 Moreover, the use and activation of emergency medical services, consisting of professionals trained in the interpretation of 12-lead EKG and the possibility of transmitting the electrocardiographic tracing elsewhere (telemetry), culminating with direct patient transportation to the interventional laboratory, have been shown to significantly reduce reperfusion times and mortality rates at six months for these patients.11,12

The role of the pharmaco-invasive strategy in this context is still debatable. Although the immediate performance of PCI after fibrinolysis as a facilitating tool has promoted increased mortality when compared with primary PCI alone,13 more recent studies have demonstrated favorable outcomes for the routine transfer of patients undergoing fibrinolysis followed by invasive stratification within the first six to 24 hours after lytic administration.14-17 Despite the natural interest in establishing a single protocol for the care of patients with STEMI, including a universal and standard reperfusion therapy, the high variability in the results comparing transfer for primary PCI and fibrinolysis is influenced by the delay to the start of treatment, the patient’s risk profile, and the experience of the local staff; the hospital structure predicts the adoption of an individualized analysis and the decision-making process based on these factors.

Study LimitationsThe limitations of this study include the fact that it was observational and nonrandomized, the limited number of patients (which hinders the inference of efficacy and safety outcomes), the inability to determine the actual interval between the patient’s admission time and the procedure start time (which is why the door-to-balloon time was chosen), and the absence of clinical information after the hospital discharge, given the high rate of morbidity and cumulative mortality in this clinical setting.

CONCLUSIONSIn spite of an integrated emergency system, which allows for an inter-hospital transfer time interval<60 minutes, referring a patient diagnosed with STEMI directly to a hospital equipped with an interventional laboratory is associated with decreased total ischemia time, reduced door-to-balloon time, improved myocardial reperfusion markers, and a non-significant decrease in hospital mortality.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.