The benefits of using thrombus aspiration catheters during primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), to obtain better coronary flow and myocardial perfusion and reducing late mortality are established in the literature. However, in the clinical practice it does not seem to be used for all patients. We tried to determine what clinical and angiographic variables have led to the indication of these devices in primary PCI at our institution.

MethodsFrom August 2006 to November 2010, 558 patients were consecutively submitted to primary PCI. Thrombus aspiration catheters were used in 79 patients (group 1), who were compared to 479 patients who did not use these devices (group 2).

ResultsGroup 1 showed a prevalence of males, smokers, large acute myocardial infarctions (AMI) and thrombotic lesions. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, direct stenting and larger diameter stents and the presence of transient coronary flow disturbances were also more frequent in group 1. Procedure success rate was high (93.7% vs. 92.3%; P=0.4) and it was similar between groups. At hospital discharge, the incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (6.3% vs. 6.5%; P=0.6), death (5.1% vs. 3.8%; P=0.58), stroke (1.3% vs. 0.4%; P=0.09), reinfarction (0 vs. 2.3%; P=0.17) was not different between groups.

ConclusionsThrombus aspiration catheters have been used in 15% of primary PCIs, usually in AMIs with greater extension and thrombotic burden. Despite the more severe clinical-angiographic profile of these patients the success rate is high and similar to that of low-risk patients.

Perfil de Pacientes Tratados com Cateteres de Aspiraçãode Trombos Durante Intervenção Coronária Percutânea Primária

IntroduçãoOs benefícios da utilização de cateteres de aspiração de trombos durante intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) primária, com obtenção de melhor fluxo coronário e perfusão miocárdica e redução da mortalidade tardia, já estão estabelecidos na literatura. No entanto, seu uso na prática clínica parece não estar aplicado a todos os pacientes. Procuramos saber quais variáveis clínicas e angiográficas têm norteado a indicação desses dispositivos na ICP primária em nosso meio.

MétodosNo período de agosto de 2006 a novembro de 2010, 558 pacientes foram submetidos consecutivamente a ICP primária. Em 79 pacientes foram utilizados cateteres de aspiração de trombos (grupo 1), comparativamente a 479 pacientes nos quais esses dispositivos não foram aplicados (grupo 2).

ResultadosO grupo 1 apresentou predomínio de sexo masculino, tabagistas, infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM) de maior extensão e lesões trombóticas. O uso de inibidores da glicoproteína IIb/IIIa, da técnica de stent direto e de stents de maior diâmetro e a ocorrência de distúrbios de fluxo coronário transitórios também foram mais frequentes no grupo 1. A taxa de sucesso do procedimento foi alta (93,7% vs. 92,3%; P = 0,4) e similar entre os grupos. Na alta hospitalar, a incidência de eventos cardíacos e cerebrovasculares adversos maiores (6,3% vs. 6,5%; P = 0,6), óbito (5,1% vs. 3,8%; P = 0,58), acidente vascular cerebral (1,3% vs. 0,4%; P = 0,09) e reinfarto (0% vs. 2,3%; P = 0,17) não mostrou diferenças entre os grupos.

ConclusõesCateteres de aspiração de trombos têm sido utilizados em 15% das ICPs primárias, geralmente nos IAM de maior extensão e com maior carga trombótica. Apesar da maior gravidade clínico-angiográfica desses pacientes, o sucesso do procedimento é alto e semelhante ao dos demais pacientes de menor risco.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the treatment of choice for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions (AMI) when it is performed early. The procedure can re-establish normal epicardial coronary flow in over 90% of patients, thereby reducing mortality and the rates of recurrent ischemia and reinfarction, with minimal risk of severe haemorrhagic complications.1–3

The interventionist approach to the atherothrombotic plaque using guidewires, balloon catheters, and stents during primary PCI may lead to thrombus displacement or to fragmentation, with consequent embolisation to distal coronary branches.4 This result has been verified in 15.2% of procedures, and is related to decreased coronary flow, the occurrence of no/slow-reflow phenomenon, lower rate of ST-segment normalisation, a greater enzyme elevation, worse ventricular function, and greater long-term mortality.5–7

The intracoronary aspiration devices introduced in the last decade are mechanical or manual thrombus-aspiration catheters, and are used during primary PCI. The first model uses a low-rotation mechanical engine, and the second uses aspiration through a syringe. These models have been used to perform thrombectomy and result in immediate flow improvement as well as better myocardial perfusion after the procedure.7,8 A reduction in death and reinfarction has been reported due to the use of manual aspiration devices in randomised controlled studies with follow-up of eight to 24 months after AMI.9–11 With the mechanical catheters, this benefit was also demonstrated 30 days after AMI in a recently published major study.12

Despite the well-established benefits in the literature and a classification of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B, in the current guidelines, the use of these devices is still not universally applied to patients undergoing primary PCI.1,13,14 This article aimed to characterise the profile of the patients treated in the present institution with such devices during primary PCI.

METHODSPatientsFrom August of 2006 to November of 2010, 558 primary coronary interventions were performed consecutively at the Haemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology Service of the Hospital Bandeirantes (São Paulo, SP, Brazil). In 79 of these procedures, thrombus aspiration catheters were used (group 1). These procedures were compared with those (479) in which the catheters were not used (group 2).

Data were prospectively collected and stored in a computerised database.

The clinical and angiographic profiles were analysed, as well as those related to the procedure, in addition to the success rate and clinical progression until discharge from the hospital.

Percutaneous coronary interventionAlmost all interventions were performed through femoral access. In a few cases, radial or brachial access was chosen. The surgeons were responsible for selecting the technique and the materials to be used during the procedure. They were also responsible for identifying the necessity of aspiration catheters and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. For thrombectomy or thrombus aspiration, all devices used were manual aspiration catheters Pronto® and Pronto® V3 (Vascular Solutions – Minneapolis, USA), Diver™ (Invatec – Brescia, Italy), or Export® (Medtronic - Minneapolis, USA). At the beginning of the procedure, a 70 U/kg to 100 U/ kg dose of unfractionated heparin (50 U/kg to 70 U/ kg in the case of concomitant use of glycoprotein IIb/ IIIa inhibitors) was administered. The no/slow-reflow phenomenon was pharmacologically treated with intracoronary administration of adenosine and/or isosorbide mononitrate associated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. All patients received dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid (loading dose: 200mg and 100mg/day for maintenance) and clopidogrel (loading dose: 300–600mg and 75mg/day for maintenance) or ticlopidine (250mg every 12 hours). Femoral sheaths were removed four hours after heparin administration. Radial sheaths were removed immediately after the end of the procedure.

Angiographic analysis and definitionsThe analysis were performed by expert surgeons in at least two orthogonal projections using digital quantitative coronary angiography. The angiographic criteria from the Brazilian National Centre for Cardiovascular Interventions (CENIC) of the Brazilian Society of Haemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology (SBHCI) were used in the present study. The criteria of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association for type of lesion were used.15 Lesions > 20mm were considered long. For the evaluation of coronary flow before and after the procedure, the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) classification was used.16 The success of the procedure was defined as angiographic success (residual stenosis < 30% with TIMI 3 flow) and absence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), including death, reinfarction, stroke, and emergency coronary artery bypass graft surgery. 1 Reinfarction was defined as the presence of electrocardiographic alterations (new ST-segment elevation or new Q waves) and/or angiographic evidence of targeted vessel occlusion. Surgery performed immediately after percutaneous coronary intervention was considered an emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. The analysis also considered all-cause mortality and cardiac mortality (cardiogenic shock, heart failure, AMI, cardiac rupture, arrhythmia, and sudden death) during hospital stay.

Statistical analysisData stored in Oracle databases were plotted in Excel worksheets in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), release 15.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation and categorical variables were expressed as percentiles. The associations among the continuous variables were evaluated with Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). The associations among the categorical variables were evaluated by the chi-squared test or by Fischer’s exact test in 2 x 2 contingency tables. In greater contingency tables, the chi-squared test or the G tests were applied. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

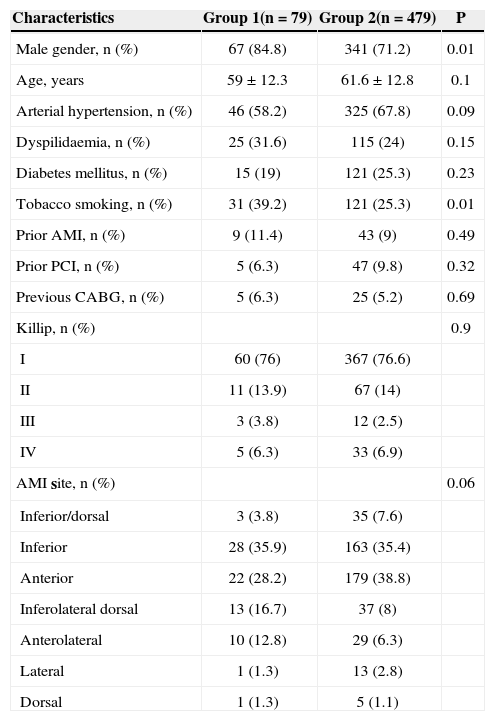

RESULTSTable 1 presents the clinical characteristics of both groups.

Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristics | Group 1(n=79) | Group 2(n=479) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 67 (84.8) | 341 (71.2) | 0.01 |

| Age, years | 59±12.3 | 61.6±12.8 | 0.1 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 46 (58.2) | 325 (67.8) | 0.09 |

| Dyspilidaemia, n (%) | 25 (31.6) | 115 (24) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 15 (19) | 121 (25.3) | 0.23 |

| Tobacco smoking, n (%) | 31 (39.2) | 121 (25.3) | 0.01 |

| Prior AMI, n (%) | 9 (11.4) | 43 (9) | 0.49 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 5 (6.3) | 47 (9.8) | 0.32 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 5 (6.3) | 25 (5.2) | 0.69 |

| Killip, n (%) | 0.9 | ||

| I | 60 (76) | 367 (76.6) | |

| II | 11 (13.9) | 67 (14) | |

| III | 3 (3.8) | 12 (2.5) | |

| IV | 5 (6.3) | 33 (6.9) | |

| AMI site, n (%) | 0.06 | ||

| Inferior/dorsal | 3 (3.8) | 35 (7.6) | |

| Inferior | 28 (35.9) | 163 (35.4) | |

| Anterior | 22 (28.2) | 179 (38.8) | |

| Inferolateral dorsal | 13 (16.7) | 37 (8) | |

| Anterolateral | 10 (12.8) | 29 (6.3) | |

| Lateral | 1 (1.3) | 13 (2.8) | |

| Dorsal | 1 (1.3) | 5 (1.1) |

AMI=acute myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; n=number of patients; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

In 14.1% of primary PCI procedures, an aspiration catheter was used; these patients comprised group 1. This group had a greater number of male patients (84.8% vs. 71.2%; P=0.01) and smokers (39.2% vs. 25.3%; P=0.01), when compared with group 2. There were no differences between the groups regarding age, presence of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyspilidaemia, prior myocardial infarction, prior PCI, prior CABG surgery, infarction location detected by electrocardiography, or functional Killip class.

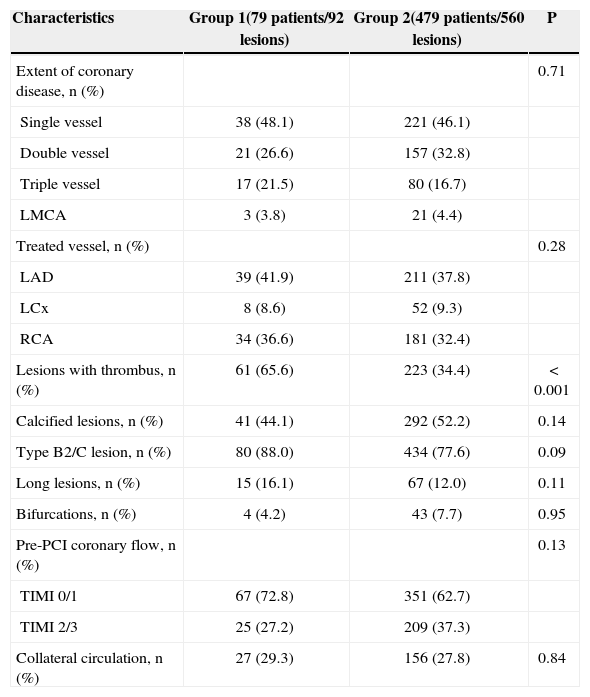

Tables 2 and 3 present the angiographic and procedural characteristics.

Angiographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Group 1(79 patients/92 lesions) | Group 2(479 patients/560 lesions) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extent of coronary disease, n (%) | 0.71 | ||

| Single vessel | 38 (48.1) | 221 (46.1) | |

| Double vessel | 21 (26.6) | 157 (32.8) | |

| Triple vessel | 17 (21.5) | 80 (16.7) | |

| LMCA | 3 (3.8) | 21 (4.4) | |

| Treated vessel, n (%) | 0.28 | ||

| LAD | 39 (41.9) | 211 (37.8) | |

| LCx | 8 (8.6) | 52 (9.3) | |

| RCA | 34 (36.6) | 181 (32.4) | |

| Lesions with thrombus, n (%) | 61 (65.6) | 223 (34.4) | < 0.001 |

| Calcified lesions, n (%) | 41 (44.1) | 292 (52.2) | 0.14 |

| Type B2/C lesion, n (%) | 80 (88.0) | 434 (77.6) | 0.09 |

| Long lesions, n (%) | 15 (16.1) | 67 (12.0) | 0.11 |

| Bifurcations, n (%) | 4 (4.2) | 43 (7.7) | 0.95 |

| Pre-PCI coronary flow, n (%) | 0.13 | ||

| TIMI 0/1 | 67 (72.8) | 351 (62.7) | |

| TIMI 2/3 | 25 (27.2) | 209 (37.3) | |

| Collateral circulation, n (%) | 27 (29.3) | 156 (27.8) | 0.84 |

RCA=right coronary artery; LCx=circumflex coronary artery; LAD=anterior descending artery; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; LMCA=left main coronary; TIMI=thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Procedure-related Characteristics

| Characteristics | Group 1(79 patients/92 lesions) | Group 2(479 patients/560 lesions) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Door-to-balloon time, minutes | 56.9±110.1 | 69.6±138.3 | 0.6 |

| Pre-procedure CK-MB, ng/mL | 127.7±147.3 | 85.3±134.6 | 0.01 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 38 (48.1) | 147 (30.7) | 0.001 |

| Direct stenting technique, n (%) | 50 (54.4) | 232 (41.5) | 0.02 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.3±0.6 | 3.1±0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Stent length, mm | 20.6±6.6 | 20.2±6.6 | 0.65 |

| Transitory no/slow-reflow | 13 (16.8) | 32 (6.7) | < 0.001 |

| Post-PCI coronary flow, n (%) | 0.58 | ||

| TIMI 0/1 | 0 | 10 (1.8) | |

| TIMI 2 | 8 (8.7) | 42 (7.5) | |

| TIMI 3 | 84 (91.3) | 508 (90.7) | |

| Degree of stenosis, (%) | |||

| Pre | 95.1±12.6 | 93.0±12.5 | 0.17 |

| Post | 10.1±4.3 | 10.9±7.5 | 0.58 |

| Success of the procedure, n (%) | 74 (93.7) | 442 (92.3) | 0.4 |

CK-MB=creatine kinase-MB fraction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI=thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Group 1 presented with a higher pre-PCI creatine kinase-MB fraction (127.7ng/mL vs. 85.3ng/mL; P=0.01). Thrombotic lesions (65.6% vs. 34.4%; P < 0.001), the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (48.1% vs. 30.7%; P=0.001), and the use of direct stenting (54.4% vs. 41.5%; P=0.02) were also more frequent in this group. Larger diameter stents were also used (3.3±0.6mm vs. 3.1±0.6mm; P < 0.001). Transient coronary flow disturbances (no/slow-reflow) during PCI (16.8% vs. 6.7%; P < 0.001) were more frequent in group 1.

No differences were observed between the groups regarding the targeted vessel, extension and complexity of the coronary disease, degree of the collateral circulation, pre-procedure coronary flow (TIMI), door-to-balloon time (56.9±110.1minutes vs. 69.6±138.3minutes; P=0.6), or success of the procedure (93.7% vs. 92.3%; P=0.4). Despite a greater occurrence of transient coronary flow disturbances in group 1, these phenomena were successfully treated pharmacologically; therefore, the groups did not show differences in post-procedure TIMI flow (91.3% vs. 90.7% for groups 1 and 2, respectively; P=0.576).

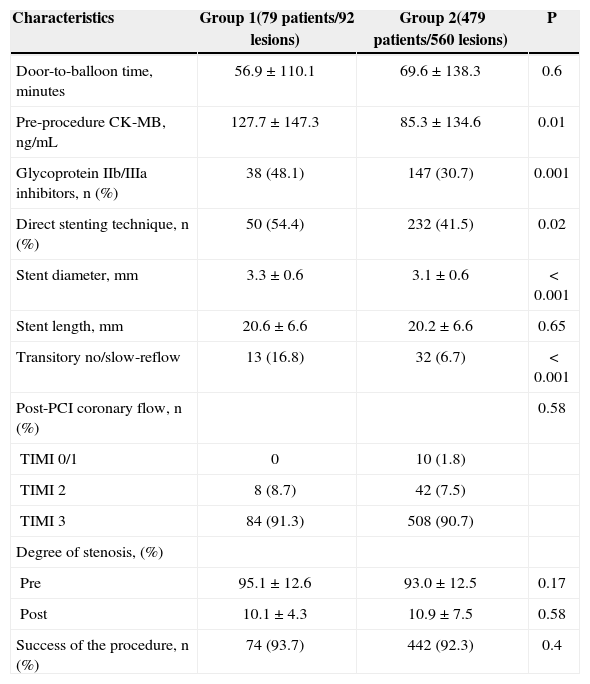

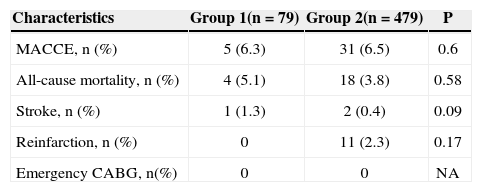

Hospital outcomes (Table 4) of the primary PCI showed no differences between the groups regarding the occurrence of MACCE, (6.3% vs. 6.5%; P=0.6), in-hospital mortality (5.1% vs. 3.8%; P=0.58), stroke (1.3% vs. 0.4%; P=0.09), or reinfarction (0 vs. 2.3%; P=0.17). No patient underwent emergency CABG surgery.

Clinical Outcomes During Hospital Stay

| Characteristics | Group 1(n=79) | Group 2(n=479) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE, n (%) | 5 (6.3) | 31 (6.5) | 0.6 |

| All-cause mortality, n (%) | 4 (5.1) | 18 (3.8) | 0.58 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0.09 |

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 0 | 11 (2.3) | 0.17 |

| Emergency CABG, n(%) | 0 | 0 | NA |

MACCE=major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; n=number of patients; NA=non-applicable; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

The presence of thrombus provides suboptimal results in PCI due to its potential displacement and fragmentation, leading to distal macro- and microembolisation. Macroembolisation is defined as a failure of distal filling, with a sudden interruption in one of the branches of the peripheral coronary arteries of the vessel related to infarction, distal to the angioplasty site. Microembolisation results in microvascular dysfunction, which is evaluated through microbubble echocardiography in the risk area after primary PCI. These events have been associated with TIMI flow < 3 and with reduced myocardial blush in spite of the reopened artery (the no/slow-reflow phenomenon), slower ST-segment resolution rate, higher enzyme elevation, lower left ventricular ejection fraction and higher long-term mortality rates.4–6,17

Thrombectomy, or mechanical removal of the thrombus from the coronary artery, can improve the prognosis after AMI, since, in theory, it can reduce the chances of distal embolisation of thrombus and its fatal consequences.

Thrombectomy leads to a better flow and immediate myocardial perfusion, as well as a reduction of infarction size and microvascular lesion (through enzymes and magnetic resonance), faster resolution of the ST-segment elevation, and higher myocardial blush, especially with the use of manual aspiration devices.18–20 Several randomised and controlled studies have demonstrated a reduction in death and reinfarction in patients with late follow-up at eight to 24 months after the AMI.9–11

However, there is controversy regarding the use of aspiration devices, specifically whether they can be used universally or only for specific angiographic/clinical groups. The randomised study ‘Impact of thrombectomy with EXPort catheter in infarct-related artery during primary percutaneous coronary intervention (EXPIRA)’ considered as inclusion criteria the thrombus load (TIMI IIIA classification)21≥3 and TIMI flow≤1, limiting their conclusions to this specific group of patients with AMI.10,18 The ‘Thrombus aspiration during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction study (TAPAS),’ the most complete study to date, presented more consistent results regarding late mortality, and included patients with AMI without angiographic restrictions.11 The clinical and angiographic variables that best translate the benefits of thrombectomy still need to be defined.

In the present study, the use of aspiration devices was more prevalent in male patients and in tobacco smokers. The close relationship between tobacco smoking and coronary atherothrombosis may help explain this fact, as there is a higher occurrence of thrombotic coronary plaques among tobacco smokers.22 The greater increase in creatine kinase-MB fraction (CK-MB) before intervention demonstrates that thrombectomy was more frequently performed in more extensive infarctions.

As expected, among the angiographic features, the occurrence of thrombus-filled lesions was higher in patients in whom aspiration devices were used, regardless of the TIMI flow and the length of the coronary lesions. The thrombotic burden was not calculated, and the presence or angiographic suspicion of thrombus was only qualitatively considered. Greater use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and of transient flow disturbances during the procedure (no/slow-reflow) suggest that the thrombus burden in these patients was more significant. A greater thrombus burden predicts the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular events after the primary PCI, either during acute phase or in the late phase, making it difficult to completely position the stent apposed to the vessel wall, which could predispose to thrombosis of the prosthesis.23,24

In the procedures performed with aspiration devices, a greater number of stents were implanted without pre-dilatation with balloon catheters (direct stenting technique). This finding may be explained by the restored flow after thrombectomy, which enables the identification of the characteristics and the presence of calcification, tortuosities, and obstruction length, as well as dimensions of the stent to be implanted without requiring pre-dilation. Such observations have been made in previous publications.25

As a favourable outcome with adjunct thrombectomy, observational studies have shown the stent implant to be shorter than the original thrombus-filled lesion.19 In the present study, there was a difference regarding stent diameter. The group in which aspiration devices were used received larger stents. The interaction between the thrombus and the production of vessel-constricting endothelial substances, which influence the calibre of the artery, may explain this finding.23

The success rates of the procedures in both groups studied were high, and the incidence of MACCE, reinfarction, stroke, emergency CABG surgery, and death were low and similar between the groups.

Limitations of the studyAmong the limitations of this study are the retrospective analysis of the data between two cohorts with non-adjustable clinical variables, the non-availability of parameters to evaluate post-aspiration myocardial perfusion (myocardial blush and ST-segment resolution), the absence of late patient follow-up, and the fact that the procedures were performed in more than one centre.

CONCLUSIONSThrombus aspiration catheters were used in approximately 15% of patients undergoing primary PCI, usually in AMIs with greater extension and thrombotic burden. Despite the more severe clinical-angiographic profile of this group, the success rate of the procedure was high and similar to that of low-risk patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.