Treatment of ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction has primary percutaneous coronary intervention as the preferred method of reperfusion. This study aimed to evaluate in-hospital outcomes of patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction according to the total ischemic time until performing primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

MethodsSingle-center registry of patients admitted with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention between March/2012 and February/2014, followed from admission to hospital discharge, and compared according to the total ischemic time (Group 1: symptom onset-to-balloon time<6hours; Group 2: symptom onset-to-balloon time>6 and<12hours).

ResultsTwo hundred seventy nine patients underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention, 118 in Group 1 (42.3%) and 161 in Group 2 (57.7%). Group 2 was older, had higher prevalence of hypertension, fewer smokers, more patients in Killip-Kimball class>2 and lower primary percutaneous coronary intervention success rate. The incidences of death or non-fatal infarction (11.0% vs. 18.6%; p=0.08), death (8.5% vs. 16.8%; p=0.04) and acute renal failure (7.6% vs. 19.9%; p<0.01) were greater in Group 2.

ConclusionsPatients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention with symptom onset-to-balloon time>6hours presented higher clinical complexity and worse in-hospital outcomes when compared to patients treated earlier. Joint actions in different critical areas of patient care are essential to increase treatment efficacy and reduce adverse outcomes.

Resultados da Interveção Coronária Percutânea Primária de Acordo com o Tempo Total de Isquemia

IntrodçãoO tratamento do infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento de ST tem a intervenção coronária percutânea primária como método preferencial de reperfusão. Este estudo teve como objetivo avaliar a evolução hospitalar de pacientes com infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento de ST, conforme o tempo total de isquemia, até a realização de intervenção coronária percutânea primária.

MétodosRegistro unicêntrico, de pacientes admitidos com infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento de ST submetidos à intervenção coronária percutânea primária entre março de 2012 e fevereiro de 2014, acompanhados da admissão até a alta hospitalar e comparados conforme o tempo total de isquemia (Grupo 1: tempo dor-balão<6 horas; Grupo 2: tempo dor-balão>6 e<12 horas).

ResultadosForam submetidos à intervenção coronária percutânea primária 279 pacientes, sendo 118 do Grupo 1 (42,3%) e 161 do Grupo 2 (57,7%). O Grupo 2 apresentou idade mais avançada, maior prevalência de hipertensão arterial, menor proporção de tabagistas, maior número de pacientes em classe Killip-Kimball>2 e menor taxa de sucesso da intervenção coronária percutânea primária. As incidências de óbito ou infarto não fatal (11,0% vs. 18,6%; p=0,08), óbito (8,5% vs. 16,8%; p=0,04) e insuficiencia renal aguda (7,6% vs. 19,9%; p<0,01) foram maiores no Grupo 2.

ConclusõesPacientes com infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento de ST submetidos à intervenção coronária percutânea primária com tempo dor-balão>6 horas apresentaram maior complexidade clínica e pior evolução hospitalar em relagao àqueles tratados mais precocemente. Ações conjuntas em diversos pontos críticos da assistência ao paciente são fundamentais para aumentar a eficácia do tratamento e reduzir os desfechos adversos.

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has a high incidence and is currently a leading cause of death in Brazil, in addition to generating large expenditures, of both financial and technological resources, by the country's health care systems. The increasing number of cases of AMI, particularly in developing countries, is presently one of the most relevant public health issues.1

There are very robust, evidence-based scientific data regarding the clinical benefit of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) in acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (STEMI).2–5 However, some obstacles can directly influence the treatment of patients with AMI. In this context, primary PCI should be made available in centers with interventional cardiology training, and reducing the time between symptom onset and the procedure is associated with a higher rate of culprit artery patency, smaller infarct size, and lower mortality.6 For that to occur, it is necessary the combine the actions of several professionals in an integrated and efficient system, which includes symptom recognition by population, disease diagnosis at the service of arrival, patient transportation to the referral service, and finally, the engagement of the interventional cardiology team.

In the guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology, the indication for primary PCI from up to 90 minutes of the first medical contact for patients with STEMI in the acute phase (with symptoms that started less than 12 hours before) receives Class I recommendation, level of evidence A.7 Although the performance of primary PCI within 12 hours of the onset of STEMI is universally accepted, agility and the reduction of the delay until coronary reperfusion therapy are constantly sought. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the clinical evolution of patients with STEMI, according to the total ischemic time until the performance of the PPCI.

METHODSStudy design and populationThis was an observational study of a single center registry of patients admitted with STEMI, submitted to PPCI between March 2012 and February 2014 at Hospital Evangélico de Vila Velha, located in Vila Velha (ES), followed from hospital admission until discharge or death. This series included consecutive patients older than 18 years who underwent primary PCI within 12 hours of the onset of AMI, with persistent ST-segment elevation or new left bundle branch block on ECG, and treated by the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS). Patients undergoing primary PCI with STEMI onset of more than 12 hours were excluded from the study, as well as those for whom there were doubts about the diagnosis of STEMI by the Clinical Cardiology and Interventional Cardiology staff.

Patients included in the study were divided into two groups according to the total time of ischemia; Group 1, with symptom-onset-to-balloon time<6hours, and Group 2, with symptom-onset-to-balloon time>6 and<12hours.

The data obtained from the medical records were stored prospectively in the service in registry format. All patients signed an informed consent prior to the procedures. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee under protocol number 492.764.

PROCEDURESHospital Evangélico de Vila Velha is a referral center of SUS for cardiovascular emergencies in the metropolitan region of Vitoria. The Service of Interventional Cardiology and Hemodynamics comprises medical and nursing staff in attendance 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, working together with the clinical cardiology team.

All patients were assessed regarding the emergency nature of the primary PCI procedure, and patients were taken to the invasive procedure room as soon as possible after a communication with the emergency room team. Patients received a loading dose of 200 to 300mg of acetylsalicylic acid and 300 to 600mg of clopi-dogrel, or 180mg of ticagrelor. The use of morphine, sublingual/intravenous nitrate, or beta-blocker was at the discretion of the attending physician. All underwent full heparinization with unfractionated heparin immediately before the intervention (60 to 100 U/kg).

The PPCI was performed as recommended by guidelines,7 and the vascular access route was at the interventionist's discretion. Pre-dilation, post-dilation, and administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were performed at the surgeon's discretion.

Definitions and OutcomesIn addition to the time of symptom onset-to-balloon, the following times were also analyzed: symptom onset-to-door time (from symptom onset to arrival at the first health service); inter-hospital transfer time (time elapsed from arrival at the first health service until arrival at the referral service, i.e., the emergency room of Hospital Evangélico de Vila Velha), for cases that were not initially seen at the referral service; and door-to-balloon time (interval between arrival at the emergency referral service to the performing PPCI).

Hospitalization was recorded in days, from the day of admission, considered as zero day. In the analysis of length of hospitalization, only patients who were discharged to home were considered, excluding those who died during the hospitalization.

Regarding mortality, hospital mortality was considered as cases of death from any cause after the procedure. Non-fatal myocardial infarction was defined as elevation of CK-MB to three times above baseline or troponin five times above baseline, in association with recurrent symptoms of myocardial ischemia and/or ECG changes compatible with ischemia.

The primary endpoint was the combined occurrence of cardiac events, death from any cause, or non-fatal AMI (with or without new coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG]) during hospitalization. Secondary outcomes were isolated occurrences of death and non-fatal myocardial infarction, in addition to acute renal failure (characterized by increased serum creatinine>50% from baseline or need for dialysis) and major bleeding according to the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) criteria.8

Statistical AnalysisIn the descriptive analysis, categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 11.0 for Windows and the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test were used, as appropriate, to compare the qualitative variables, whereas Student's i-test was used for quantitative variables; p-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant, with a confidence interval of 95%.

RESULTSBetween March 2012 and February 2014, 279 patients with STEMI were admitted and underwent PPCI, of whom 118 (42.3%) with symptom onset-to-balloon time<6hours were allocated to Group 1, whereas 161 with symptom onset-to-balloon≥6hours and<12hours were allocated to Group 2.

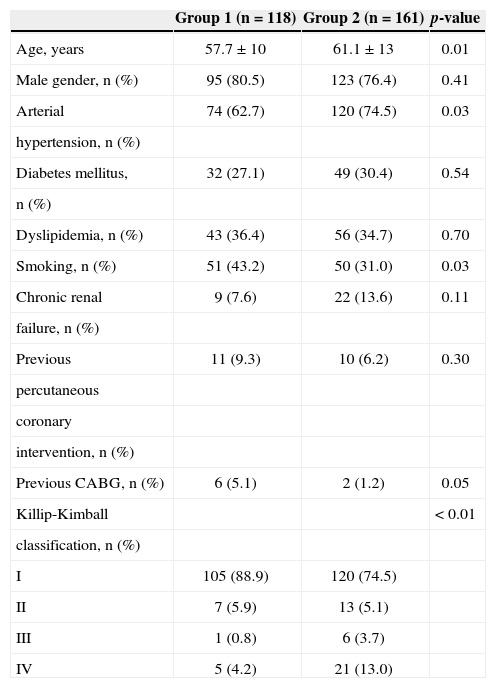

Patients in Group 2 were older and had higher prevalence of hypertension and lower rate of current smoking. This group showed more severe clinical presentation of STEMI at hospital admission, according to the Killip-Kimball classification, with 24.8% in class≥2 and 11.0% in Group 1 (p<0.01). The baseline clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Basal clinical characteristics

| Group 1 (n=118) | Group 2 (n=161) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.7±10 | 61.1±13 | 0.01 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 95 (80.5) | 123 (76.4) | 0.41 |

| Arterial | 74 (62.7) | 120 (74.5) | 0.03 |

| hypertension, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus, | 32 (27.1) | 49 (30.4) | 0.54 |

| n (%) | |||

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 43 (36.4) | 56 (34.7) | 0.70 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 51 (43.2) | 50 (31.0) | 0.03 |

| Chronic renal | 9 (7.6) | 22 (13.6) | 0.11 |

| failure, n (%) | |||

| Previous | 11 (9.3) | 10 (6.2) | 0.30 |

| percutaneous | |||

| coronary | |||

| intervention, n (%) | |||

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 6 (5.1) | 2 (1.2) | 0.05 |

| Killip-Kimball | < 0.01 | ||

| classification, n (%) | |||

| I | 105 (88.9) | 120 (74.5) | |

| II | 7 (5.9) | 13 (5.1) | |

| III | 1 (0.8) | 6 (3.7) | |

| IV | 5 (4.2) | 21 (13.0) |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

The mean duration of STEMI until the performance of PPCI was 3.7±1.4hours in Group 1 and 11.4±2.0hours in Group 2. A total of 83.0% of patients in Group 1 and 84.4% in Group 2 (p=0.75) needed an inter-hospital transfer to undergo primary PCI. Analysis of partial delay times to PPCI showed, respectively, in Groups 1 and 2, symptom onset-to-door of 1.2±0.9hours vs. 3.5±2.1hours (p<0.01), duration of inter-hospital transfer of 2.5±1.0hours vs. 6.0±2.3hours (p<0.01), and door-to-balloon time of 62±39minutes vs. 140±84minutes (p<0.01).

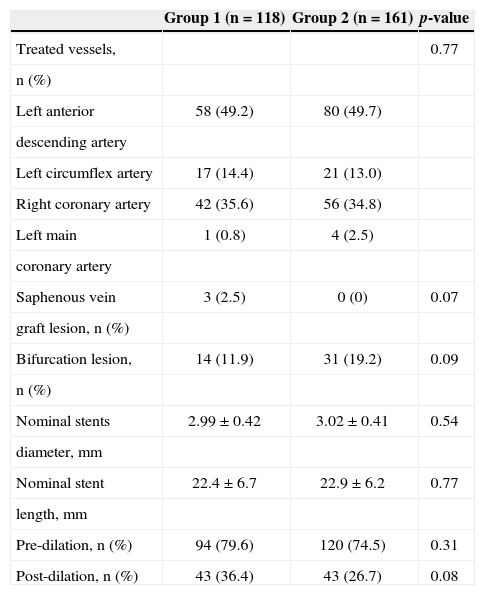

In total, the vascular access route used for PPCI was the femoral artery in 93.5% of procedures, whereas the radial approach was used in the remaining cases. A total of 351 coronary stents were implanted, all bare-metal, with a mean of 1.3±0.5 stents per patient. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were administered to 33.0% of patients in Group 1 and 32.9% of patients in Group 2 (p=0.90). Flow disturbances (slow-flow or no-reflow) after recanalization of the culprit vessel occurred in 21.1% patients in Group 1 and 26.0% in Group 2 (p=0.34). After PPCI, staged PCI procedure was performed in 34.7% and 2 7.9% of patients, respectively (p=0.22). Table 2 shows the angiographic characteristics and the treated vessels in the two groups.

Angiographic characteristics

| Group 1 (n=118) | Group 2 (n=161) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treated vessels, | 0.77 | ||

| n (%) | |||

| Left anterior | 58 (49.2) | 80 (49.7) | |

| descending artery | |||

| Left circumflex artery | 17 (14.4) | 21 (13.0) | |

| Right coronary artery | 42 (35.6) | 56 (34.8) | |

| Left main | 1 (0.8) | 4 (2.5) | |

| coronary artery | |||

| Saphenous vein | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0.07 |

| graft lesion, n (%) | |||

| Bifurcation lesion, | 14 (11.9) | 31 (19.2) | 0.09 |

| n (%) | |||

| Nominal stents | 2.99±0.42 | 3.02±0.41 | 0.54 |

| diameter, mm | |||

| Nominal stent | 22.4±6.7 | 22.9±6.2 | 0.77 |

| length, mm | |||

| Pre-dilation, n (%) | 94 (79.6) | 120 (74.5) | 0.31 |

| Post-dilation, n (%) | 43 (36.4) | 43 (26.7) | 0.08 |

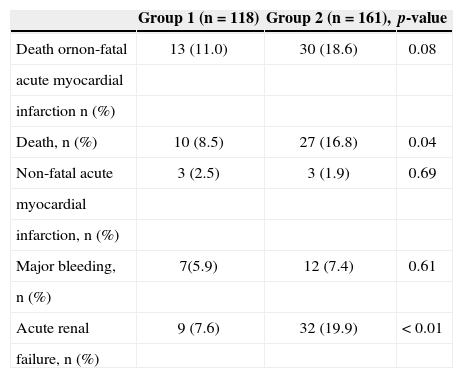

The success rate of primary PCI procedure was 94.1% in Group 1 and 85.1% in Group 2 (p=0.01). Among patients who were discharged by the medical team, the mean hospitalization was 7.9±5.2days in Group 1 and 9.2±6.1days in Group 2 (p=0.06). Adverse outcomes and complications observed during the hospitalization period are shown in Table 3.

Incidence of adverse cardiac events and in-hospital complications

| Group 1 (n=118) | Group 2 (n=161), | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death ornon-fatal | 13 (11.0) | 30 (18.6) | 0.08 |

| acute myocardial | |||

| infarction n (%) | |||

| Death, n (%) | 10 (8.5) | 27 (16.8) | 0.04 |

| Non-fatal acute | 3 (2.5) | 3 (1.9) | 0.69 |

| myocardial | |||

| infarction, n (%) | |||

| Major bleeding, | 7(5.9) | 12 (7.4) | 0.61 |

| n (%) | |||

| Acute renal | 9 (7.6) | 32 (19.9) | < 0.01 |

| failure, n (%) |

The delay in the implementation of coronary reperfusion therapy in STEMI has been the subject of discussion regarding the adoption of health policies, and has shown to be an important adverse prognostic predictor.9-11 In this study, increased time from symptom onset to the performance of PPCI was directly related to the occurrence of serious adverse events during hospitalization, including mortality.

There is great difficulty in determining the causal relationship between the increase in the time of STEMI evolution and clinical complexity. This study identified an older mean age and a higher prevalence of hypertension in Group 2, although with a lower proportion of smokers in this group. Other clinical variables such as gender, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia showed no statistically significant differences between groups. Elderly patients and those with more comorbidity may have atypical clinical pictures as the initial manifestation of AMI, which may explain delays in several points of the healthcare network when treating AMI, culminating in significant increase in symptom onset-to-balloon time.

The severity of the clinical picture at hospital admission in STEMI was higher in patients from Group 2, with a higher proportion of individuals in classes II, III, and IV of Killip-Kimball, when compared with Group 1. Again, it was not possible to determine clearly whether the cause of clinical deterioration was the delay until arrival at the referral emergency room service, or if the opposite way should be considered - that the severity of the case is the greatest cause of delay, possibly requiring initial clinical stabilization, endotracheal intubation, and adequately equipped mobile units to perform inter-hospital transfer, which can lead to delay until the primary PCI.

The analysis of time delays during the phases of STEMI care is essential to identify deficiencies in the health system. It was observed that there was considerable delay at several points in time, from the identification of the clinical picture and transportation of the patient to a health service until the transfer and performance of primary PCI in the referral service. A particular point of concern was the mean time for inter-hospital transfer of more than two hours, including in Group 1. In a prior publication, Brazilian data demonstrated that the fact that patients will initially seek a Basic Health Unit substantially increases the time of evolution of STEMI until coronary reperfusion therapy.11 In the present study, the delay in the referral service (door-to-balloon) was abbreviated whenever possible, reaching a mean door-to-balloon time of the entire sample of 104±95min (62±39minutes in Group 1 and 140±84minutes in Group 2). The work of the interventional cardiology team in attendance played a significant role in optimizing this step of assistance to AMI.

The lowest total time of ischemia (symptom-onset-to-balloon), the object of this research, was associated with lower incidence of clinical outcomes in the treatment of STEMI with PPCI, as previously demonstrated.12 In an electrocardiographic subanalysis of the PLATelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial, 70% of patients randomized in the range 3 to 6 hours of symptom onset exhibited ST-segment resolution, compared to 51% of those randomized after 6 hours.13 A similar result was found by Andrade et al.,14 who demonstrated the association of longer ischemic time with incomplete resolution of ST-segment elevation.

The survival benefits and other relevant outcomes, associated with a lower symptom onset-to-balloon time, can be observed even in long-term evolution.15–17 However, the measurement of this time interval, unlike the door-to-balloon time, is subject to bias, such as the uncertainty of the time of symptom onset by patients and variations in the temporal course of myocardial necrosis development. Still, it should be taken into account, as it reflects the results of joint activities at several critical points of care for AMI, including identification of symptoms, accessibility, and pre-hospital care.15

Thus, aggressive goals in STEMI assistance policies must be sought in order to promote flexibility in care. However, in Brazil, the prescription for coronary reperfusion therapies in the setting of AMI is far from ideal, with gaps and missed opportunities for treatment, based on the directions of the current guidelines.18 In 2013, Correia et al.19 described the effectiveness of an assistance quality protocol to reduce door-to-balloon time in STEMI. Comparing the protocol pre-implementation period with successive periods over 22 months, there was progressive reduction of the time described, with the last patients included reaching a time of 116±29minutes – comparable to the times obtained in the present study. It is noteworthy that the systematic measurement of door-to-balloon time can disclose the inadequacy of the process, and that the adoption of an evidence-based protocol can improve the performance of medical services in acute myocardial infarction.

Results of a Brazilian study brought to light important data on current clinical outcomes of AMI in Brazil. The Acute Coronary Care Evaluation of Practice Registry (ACCEPT) registry had the participation of 47 centers of excellence and included 2,475 patients with acute coronary syndrome, between August 2010 and December 2011. PCI was performed in 75.2% of cases of STEMI and the mean time of delay until PPCI was 125±90minutes. Cardiac mortality in STEMI, after dividing those submitted or not to CABG, was 2.0% vs. 8.1% (p<0.001).18

Efficient public systems for the treatment of AMI should be adapted to the reality of each region of the world, and are desirable, as their implementation can shorten any delay times to treatment access. When barriers to early accessibility are removed, the effectiveness of the treatment increases and adverse outcomes are reduced. Therefore, it is possible to reduce mortality from AMI, reduce cardiac sequelae in the long term, improve the quality of life – which is directly related to quality of care in health and its preventive measures – and redirect economic resources of public health policies to meet other needs, such as primary prevention.

Despite showing significant results in agreement with previously published studies, this study has limitations. In particular, its observational nature and small sample size are emphasized, as well as the fact that it was a sample from a specific region, which restricts data interpretation. As only the univariate analysis was performed for comparison purposes, it was not possible to establish a clear and independent causal association between longer symptom onset-to-balloon time and in-hospital outcomes, as there may have been interference from unmeasured variables. Still, the possibility of information bias in relation to the times was assumed, which would be natural, due to uncertainties regarding the time of symptom onset by patients and family members.

CONCLUSIONSPatients with acute myocardial infarction with ST- segment elevation submitted to primary percutaneous coronary intervention with a total ischemic time≥6hours had a more complex clinical profile and worse in-hospital outcome than those treated earlier. Joint actions at several critical points of care, including identification of symptoms by the patient, as well as the agility of pre-hospital and hospital care, are essential to increase the effectiveness of treatment and reduce adverse outcomes.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING SOURCENone.