Previous studies have shown that primary percutaneous coronary interventions carried off-hours are related to a worse prognosis. The objective of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of patients undergoing on- and off-hours primary percutaneous coronary interventions performed at a reference cardiology center.

MethodsProspective cohort study, including 1,108 consecutive patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction divided into a group of primary percutaneous coronary intervention performed during regular working hours (on-hours: 8:00am to 8:00pm) and primary percutaneous coronary intervention during non-regular working hours group (off-hours: 8:00pm to 8:00am).

ResultsThe sample included 680 patients in the on-hours group and 428 in the off-hours group. Baseline demographic data, risk factors and Killip classification were similar in both groups; however door-to-balloon time was significantly longer in the off-hours group (84 ± 66 minutes vs. 102 ± 98 minutes; p < 0.01). Culprit vessels and pre- and post-procedure TIMI flows were not different between groups. There were no significant differences for in-hospital mortality (7.6% vs. 10.2%; p = 0.16), stent thrombosis (2.8% vs. 2.4%; p = 0.69) or major bleeding (1.9% vs. 2.1%; p = 0.50). One-year mortality was also similar (9.5% vs. 12.6%; p = 0.12). The main predictor of mortality at 1 year was Killip III/IV (OR, 10.02; 95% CI, 5.8-17.1; p < 0.01).

ConclusionsPatients with myocardial infarction have similar in-hospital clinical outcomes regardless of the time when primary percutaneous coronary intervention is performed. However, door-to-balloon time is significantly longer in patients treated during off-hours.

Resultados das Intervenções CoronáriasPercutâneas Primárias Realizadas nos Horários Diurno e Noturno

IntroduçãoEstudos demonstram que a intervenção coronária percutânea primária realizada fora do horário de rotina está relacionada a pior prognóstico. Nosso objetivo foi avaliar os desfechos da intervenção coronária percutânea primária realizada nos períodos diurno e noturno em um centro cardiológico de referência.

MétodosEstudo de coorte prospectivo que incluiu 1.108 pacientes consecutivamente atendidos por infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST, divididos nos grupos de intervenção coronária percutânea primária diurna (se realizada entre 8 e 20 horas) e de intervenção coronária percutânea primária noturna (se realizada entre 20 e 8 horas).

ResultadosIncluímos 680 pacientes no grupo diurno e 428 no grupo noturno. As características basais referentes ao perfil demográfico, fatores de risco e classificação Killip foram semelhantes em ambos os grupos; porém o tempo porta-balão foi significativamente maior no grupo noturno (84 ± 66 minutos vs. 102 ± 98 minutos; p < 0,01). Vasos culpados e fluxos TIMI pré e pós-procedimento não foram diferentes entre os grupos. Não encontramos diferenças significantes em relação à mortalidade hospitalar (7,6% vs. 10,2%; p = 0,16), trombose de stent (2,8% vs. 2,4%; p = 0,69) ou presença de sangramento maior (1,9% vs. 2,1%; p = 0,50). Em 1 ano, a mortalidade também foi semelhante (9,5% vs. 12,6%; p = 0,12). O principal preditor de mortalidade em 1 ano foi a classe III/IV de Killip (OR = 10,02; IC 95% 5,8-17,1; p < 0,01).

ConclusõesPacientes com infarto agudo do miocárdio apresentam taxas de desfechos clínicos semelhantes, independentemente do horário de realização da intervenção coronária percutânea primária. No entanto, o tempo porta-balão é significativamente maior nos pacientes tratados entre 20 e 8 horas.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) was superior to thrombolytic therapy as a method of reperfusion in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEAMI). 1−3 In addition to restoring coronary flow in over 90% of cases, this procedure is able to increase survival and reduce the rates of reinfarction and stroke related to chemical thrombolysis. 4−9 Given these benefits, PPCI have a class I indication for treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) within first 12 hours of evolution, when available in less than 2 hours from the first medical contact, and performed in qualified centers. 7,10,11.

With respect to the applicability of PPCI, several studies have suggested that the door-to-balloon time and the mortality can be high off-hours, compared to the on-hours working period. 12−15 However, data evaluating this variable have been underreported in the Brazilian literature. 16 Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of PPCI performed during the routine schedule (on-hours) and the night shift (off-hours) at a cardiology referral center.

METHODSDesignThis was an observational study with prospective data collection.

SamplePatients with AMI who underwent PPCI at a tertiary center for interventional cardiology were included in this study. Clinical and electrocardiographic diagnoses of AMI and the indication for treatment by PPCI by the physician were used as inclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were AMI > 12 hours of evolution (except for those patients in cardiogenic shock), age < 18 years, or refusal to participate in the study. All patients were interviewed at admission and signed an informed consent, previously approved by the local research ethics committee.

Procedure for PPCIThe participants received a loading dose of 300 to 500mg of acetylsalicylic acid and 300 to 600mg of clopidogrel. The use of morphine, intravenous heparin, sublingual/intravenous nitrate, or a beta-blocker was left to the discretion of the physician on duty. The patient was referred to the procedure as soon as the procedure room was available. At this institution, there is a nursing team on duty at the invasive cardiology service 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The interventional cardiologist is called by the emergency physician in case of PPCI, and the routine of the institution requires that this professional be present 30minutes after the call.

PPCI was performed as recommended by guidelines, 7 and the access was defined by the interventionist. All patients received intravenous heparin, 60 to 100 U/kg. Pre-dilation, administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, thrombus aspiration, and stent implantation were performed at the discretion of the surgeon. The use of intra-aortic balloon was restricted to patients with cardiogenic shock.

DefinitionsAMI was defined as: (1) presence of pain at rest associated with ST-segment elevation of 1mm in at least two contiguous leads, or (2) presence of pain in patients with a presumably new left bundle branch block. AMIs were classified as: type 1, spontaneous AMI related to a primary coronary event; type 2, AMI occurred secondarily to ischemia by increased demand or reduced supply of oxygen; type 3, cardiac death; type 4a, PCI-related AMI; type 4b, AMI subsequent to angiographically documented stent thrombosis; and type 5, AMI related to coronary artery bypass graft. 17

The door-to-balloon time was defined as the time elapsed between the hospital admission and the first inflation of the balloon catheter or of stent deployment (in cases of direct stenting).

Minor bleeding was defined as the presence of a clinically evident bleeding in the form of a decrease of hemoglobin between 3 and 5 g/dL, or of hematocrit between 9 and 15%. Major bleeding was defined as the occurrence of a clinically overt bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin > 5 g/dL, or of hematocrit > 15%, or as the development of hemorrhagic stroke.

Stent thrombosis was classified as a sudden occlusion of the treated vessel, angiographically confirmed during the in-hospital stay.

Clinical follow-upThe participants were followed during hospitalization by one of the study investigators, and the evaluated outcomes were: mortality, stroke, stent thrombosis, major or minor bleeding, and renal failure requiring dialysis. The clinical follow-up at 30 days and at one year was obtained by outpatient visits or by phone.

Statistical analysisData were prospectively stored in an ACCESS database and analyzed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows. Categorical variables were described as absolute numbers and percentages, and compared with the chi-squared test. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation, and compared with Student’s t-test. The Mann–Whitney test was used in cases in which the continuous variables were not normally distributed. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of mortality. A two-tailed value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTSBetween December 2009 and December 2011, 1,108 patients with AMI were treated by PPCI. 680 patients were included in the on-hours PPCI group, and 428 in the off-hours PPCI group. There was no difference between groups regarding the type of AMI: type 1 (90.1% vs. 94.8%), type 2 (2.7% vs. 1.4%), type 3 (0.1% vs. 0), and type 4a (0.9% vs. 0.5%), respectively (p = 0.14).

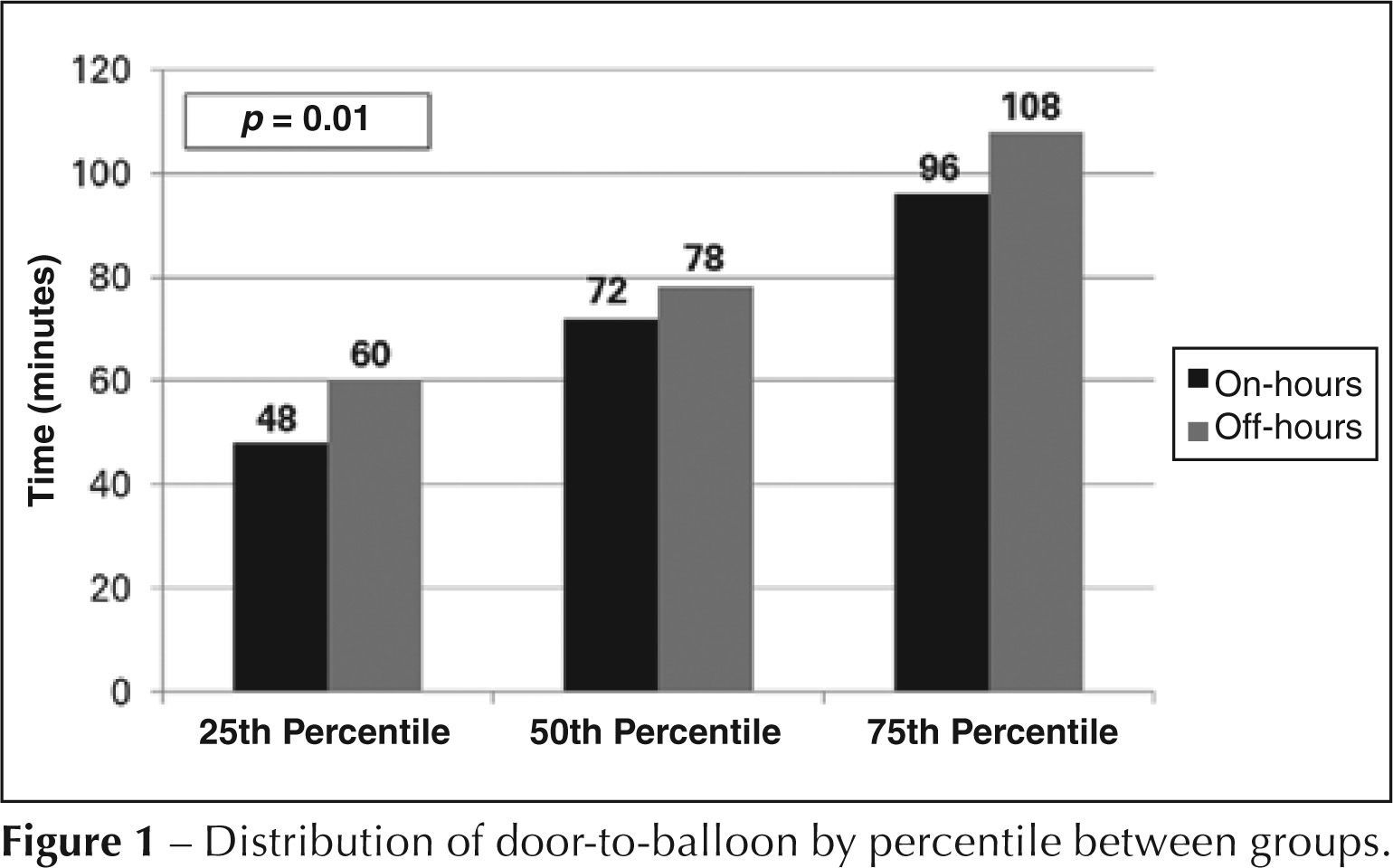

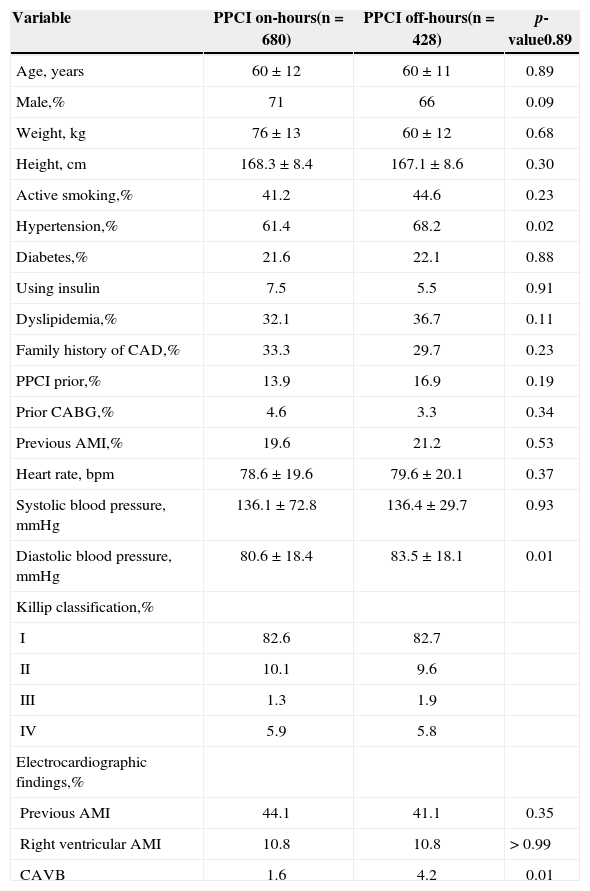

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the two groups, which, in general, were similar. Most patients were male (71% vs. 66%; p = 0.09), mean age was 60 ± 12 years vs. 60 ± 11 years (p = 0.89), one-fifth were diabetic (21.6% vs. 22.1%; p = 0.88), and most were considered Killip class I (82.6 % vs. 82.7%). Patients undergoing off-hours PPCI, however, had longer door-to-balloon time (84 ± 66 minutes vs. 102 ± 98 minutes, p < 0.01). Figure 1 shows the distribution of door-to-balloon time percentiles; it is important to note that, regardless of the time of PPCI, the door-to-balloon time was < 90 minutes in 75% of cases.

Clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics

| Variable | PPCI on-hours(n = 680) | PPCI off-hours(n = 428) | p-value0.89 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60 ± 12 | 60 ± 11 | 0.89 |

| Male,% | 71 | 66 | 0.09 |

| Weight, kg | 76 ± 13 | 60 ± 12 | 0.68 |

| Height, cm | 168.3 ± 8.4 | 167.1 ± 8.6 | 0.30 |

| Active smoking,% | 41.2 | 44.6 | 0.23 |

| Hypertension,% | 61.4 | 68.2 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes,% | 21.6 | 22.1 | 0.88 |

| Using insulin | 7.5 | 5.5 | 0.91 |

| Dyslipidemia,% | 32.1 | 36.7 | 0.11 |

| Family history of CAD,% | 33.3 | 29.7 | 0.23 |

| PPCI prior,% | 13.9 | 16.9 | 0.19 |

| Prior CABG,% | 4.6 | 3.3 | 0.34 |

| Previous AMI,% | 19.6 | 21.2 | 0.53 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 78.6 ± 19.6 | 79.6 ± 20.1 | 0.37 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 136.1 ± 72.8 | 136.4 ± 29.7 | 0.93 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 80.6 ± 18.4 | 83.5 ± 18.1 | 0.01 |

| Killip classification,% | |||

| I | 82.6 | 82.7 | |

| II | 10.1 | 9.6 | |

| III | 1.3 | 1.9 | |

| IV | 5.9 | 5.8 | |

| Electrocardiographic findings,% | |||

| Previous AMI | 44.1 | 41.1 | 0.35 |

| Right ventricular AMI | 10.8 | 10.8 | > 0.99 |

| CAVB | 1.6 | 4.2 | 0.01 |

PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CAVB, complete atrioventricular block.

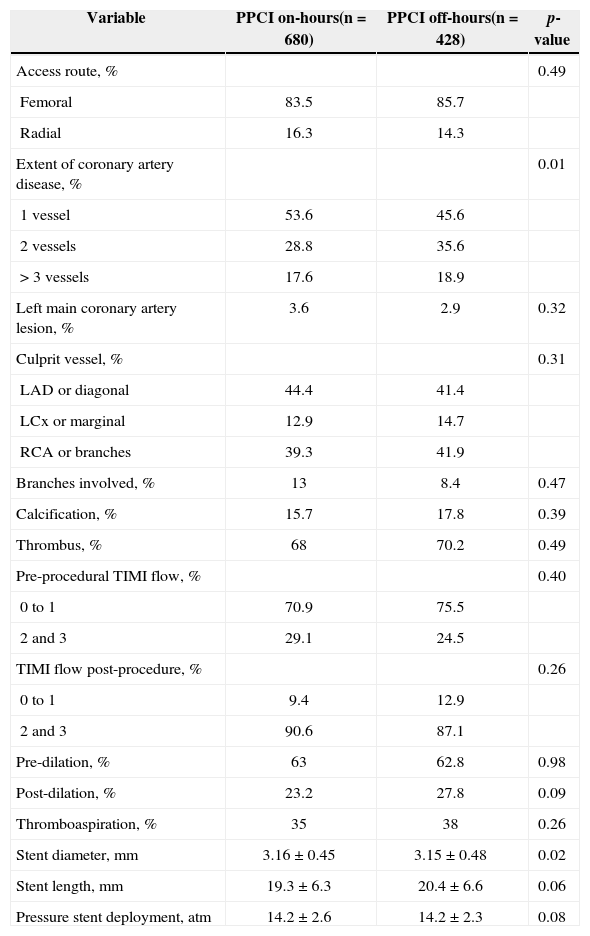

The angiographic and procedural characteristics are detailed in Table 2. The group of off-hours PPCI had more patients with involvement of two or three vessels (p < 0.01), but the culprit vessels and preand post-procedure TIMI flows were not different between groups. Thrombus aspiration devices were used in 35% of on-hours patients and in 38% of off-hours patients (p = 0.26). The use of an aortic counterpulsation balloon was also similar in both groups (3% vs. 2.4%; p = 0.70).

Angiographic and procedural characteristics

| Variable | PPCI on-hours(n = 680) | PPCI off-hours(n = 428) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access route, % | 0.49 | ||

| Femoral | 83.5 | 85.7 | |

| Radial | 16.3 | 14.3 | |

| Extent of coronary artery disease, % | 0.01 | ||

| 1 vessel | 53.6 | 45.6 | |

| 2 vessels | 28.8 | 35.6 | |

| > 3 vessels | 17.6 | 18.9 | |

| Left main coronary artery lesion, % | 3.6 | 2.9 | 0.32 |

| Culprit vessel, % | 0.31 | ||

| LAD or diagonal | 44.4 | 41.4 | |

| LCx or marginal | 12.9 | 14.7 | |

| RCA or branches | 39.3 | 41.9 | |

| Branches involved, % | 13 | 8.4 | 0.47 |

| Calcification, % | 15.7 | 17.8 | 0.39 |

| Thrombus, % | 68 | 70.2 | 0.49 |

| Pre-procedural TIMI flow, % | 0.40 | ||

| 0 to 1 | 70.9 | 75.5 | |

| 2 and 3 | 29.1 | 24.5 | |

| TIMI flow post-procedure, % | 0.26 | ||

| 0 to 1 | 9.4 | 12.9 | |

| 2 and 3 | 90.6 | 87.1 | |

| Pre-dilation, % | 63 | 62.8 | 0.98 |

| Post-dilation, % | 23.2 | 27.8 | 0.09 |

| Thromboaspiration, % | 35 | 38 | 0.26 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.16 ± 0.45 | 3.15 ± 0.48 | 0.02 |

| Stent length, mm | 19.3 ± 6.3 | 20.4 ± 6.6 | 0.06 |

| Pressure stent deployment, atm | 14.2 ± 2.6 | 14.2 ± 2.3 | 0.08 |

LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Regarding antiplatelet therapy, it was found that the loading doses of clopidogrel were similar in both groups: 300mg (16.3% vs. 19.2%; p = 0.21) and 600mg (81.5% vs. 80.3%; p = 0.69). Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor was used in 25.8% of patients in the on-hours group and in 30.2% of patients in the off-hours group (p = 0.26).

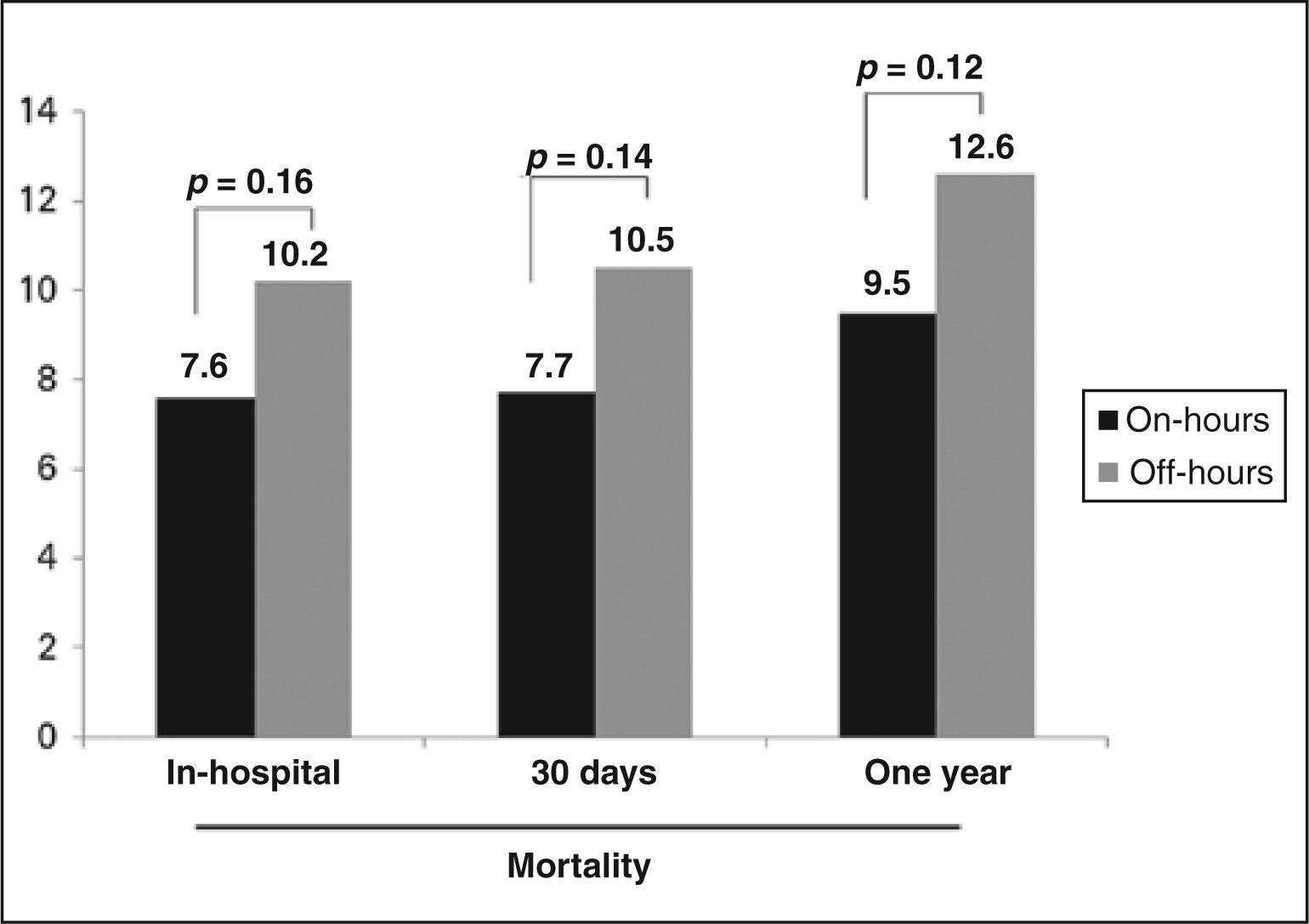

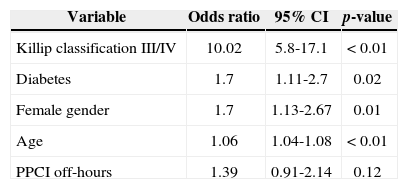

The in-hospital mortality was 7.2% in those patients treated on-hours and 10.2% in those treated off-hours (p = 0.16). There was no difference in the occurrence of stroke (0.2% vs. 0.6%; p = 0.49), stent thrombosis (2.8% vs. 2.4%; p = 0.69), major bleeding (1.9% vs. 2.1%; p = 0.50), minor bleeding (7.3% vs. 7%; p = 0.46), and need for dialysis (3.7%. vs. 3.9%; p = 0.90). There was no statistically significant difference in mortality after 30 days among patients treated in on-hours or off-hours periods (Figure 2). After one year, 97% of patients had clinical follow-up available. Predictors of one-year mortality were age, female gender, diabetes mellitus, and Killip classification III and IV at the time of hospital admission. PPCI in the off-hours period was not a predictor of mortality at one year (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of predictors of mortality at one year

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Killip classification III/IV | 10.02 | 5.8-17.1 | < 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 1.7 | 1.11-2.7 | 0.02 |

| Female gender | 1.7 | 1.13-2.67 | 0.01 |

| Age | 1.06 | 1.04-1.08 | < 0.01 |

| PPCI off-hours | 1.39 | 0.91-2.14 | 0.12 |

CI, confidence interval; PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

In this study, it was demonstrated that PPCI performed off-hours was not associated with increased mortality or more adverse clinical outcomes. In the multivariate analysis, predictors of one-year mortality were age, female gender, diabetes, and Killip classification, but not PPCI performed off-hours. These data reinforce the notion and the guidelines recommendation that PPCI should be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. This measure is of utmost importance for policy strategies on health, since approximately 50% of AMI cases occur out of regular working hours. 18 Furthermore, these results should be evaluated within the context in which this study was conducted: a high-volume referral center with highly experienced surgeons and nurses on duty 24 hours of the day in an invasive cardiology service.

Other studies have suggested that PPCI can present different results, according to the time of procedure.12,13,19 Magid et al. 14 demonstrated that the door-to-balloon time is higher depending on the time and day of the week of occurrence of the coronary event, and the present study corroborates these findings. The delay associated with PPCI performed off-hours was 18 minutes. The authors believe that this delay is due to the complexity of the procedure, which involves a larger team, compared to the administration of thrombolytic therapy. Despite this minor delay, the present study observed that less than 25% of the sample, regardless of the time (on-hours, off-hours), exceeded the 90 minutes recommended by the guidelines. 7

Although the door-to-balloon time was slightly higher in the group undergoing PPCI off-hours, no statistically significant difference was observed in relation to hospital outcomes and mortality at one year between groups. In a recent observational study, the National Cardiovascular Data Registry ® (NCDR ®) 20 showed that cardiovascular mortality has been reduced to about 5% in recent years among patients with AMI. However, Piegas and Haddad reported a death rate related to infarction of 6.35%. 21 In the present study, in-hospital mortality during on-hours was 7.6%, and 10.2% during off-hours. Although without statistical significance, a possible explanation for the higher off-hours mortality may be the greater severity of the patients cared for during the night, considering the higher prevalence of total atrioventricular block and of a more severe coronary artery compromise. Moreover, the delay in door-to-balloon time may have played an important role in the observed clinical outcomes.

Study limitationsThis study has some limitations. The inclusion of patients only from a single center may limit the extrapolation of these data to other hospitals, especially those with low volume and lack of an invasive cardiology team on duty for 24 hours. Conversely, this analysis could prompt other studies in this area to assess the reality of PPCI in Brazil, since this is the primary reperfusion method currently used. This study presented one of the largest series of PPCI ever reported in Brazil, but due to the relatively infrequent occurrence of outcomes, the number of patients may have been insufficient to identify significant differences.

CONCLUSIONSOff-hours PPCI was not associated with increased adverse cardiovascular events and bleeding episodes, but patients treated off-hours had a significantly higher door-to-balloon time versus those treated on-hours. These results support the safety of PPCI performed in shifts, as demonstrated in randomized clinical trials and also by the recommendations in the current guidelines.

Furthermore, these results should stimulate efforts in an attempt to decrease the door-to-balloon time in patients treated during off-hours.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE OF FINANCINGNone.