Epidemiological studies have shown a high prevalence and concurrence between depression and substance use. This is known as “dual diagnosis” and is associated with a worse prognosis for patients.

ObjectiveTo establish the comorbidity between depressive symptoms and substance abuse in patients admitted with acute or chronic diseases to a public hospital.

MethodsA descriptive, cross-sectional study of prevalence which included 296 patients aged 18–65, to whom the PHQ-9 and ASSIST 3.0 scales were applied to determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms and substance abuse. Other clinical and sociodemographic variables were also taken into account.

Results50.7% were women with a median age of 41 and an interquartile range of 27 years. Moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms were found in 27.4% of the patients. Alcohol was the substance with the highest consumption in the previous 3 months with 53.7%, followed by cigarettes (47.6%), marijuana (26.7%) and cocaine (14.5%). A significant association was found between severe depressive symptoms PHQ-9 ≥ 20 and problematic use of alcohol, marijuana and cocaine (ASSIST score >26); alcohol (RP 27.30, 95% CI [2.37–314.16], P = 0.01); marijuana (RP 15.00, 95% CI [3.46–64.96], P = 0.001) and cocaine (RP 10.65, 95% CI [2.23–51.10], P = 0.01).

DiscussionA high prevalence of depressive symptoms and substance use was found in patients hospitalised for non-psychiatric medical conditions, which worsens the prognosis of the underlying medical condition.

ConclusionsTo provide better hospital care for patients, we need to give visibility to the problem of dual pathology. This could be achieved by conducting more related research in these clinical scenarios.

Los estudios epidemiológicos muestran una alta prevalencia y concurrencia entre la depresión y el consumo de sustancias, lo cual es denominado «patología dual»; esta comorbilidad implica un peor pronóstico para los pacientes.

ObjetivoDeterminar la comorbilidad entre síntomas depresivos y consumo de sustancias en pacientes hospitalizados por enfermedades agudas y crónicas en un hospital público.

MetodologíaEstudio descriptivo, transversal, de prevalencia con 296 pacientes con edades entre 18 a 65 años a quienes se les aplicó el PHQ-9 y el ASSIST 3.0 para determinar la prevalencia de síntomas depresivos y consumo de sustancias psicoactivas; además, se tomaron otras variables sociodemográficas y clínicas.

ResultadosEl 50,7% fueron mujeres con una edad mediana de 41 años y rango intercuartílico de 27 años. Se encontraron síntomas depresivos moderados-severos en el 27,4% de los pacientes. El alcohol fue la sustancia de mayor consumo en los últimos 3 meses con un 53,7%, seguido por el cigarrillo (47,6%), la marihuana (26,7%) y la cocaína (14,5%). Se encontró asociación significativa entre síntomas depresivos graves PHQ-9 ≥ 20 y uso problemático de alcohol, marihuana y cocaína (puntuación ASSIST > 26); alcohol (RP 27,30, IC del 95%, 2,37-314,16; p = 0,01); marihuana (RP 15,00 IC del 95%, 3,46-64,96; p = 0,001) y cocaína (RP 10,65, IC del 95%, 2,23-51,10; p = 0,01).

DiscusiónSe encontró alta prevalencia de síntomas depresivos y uso de sustancias en pacientes hospitalizados por condiciones médicas no psiquiátricas, lo cual empeora el pronóstico de la condición médica de base.

ConclusionesPara brindar un mejor cuidado hospitalario de los pacientes, se requiere hacer visible el problema de la patología dual, lo cual podría lograrse a partir de más investigación relacionada en estos escenarios clínicos.

The term “dual diagnosis” refers to the coexistence of substance use disorders with other psychiatric disorders.1 This comorbidity is consistently above 50% in psychiatric clinical populations,2,3 reaching 17% in general populations4 and 40%–90% in some special populations (homeless people, patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection, hepatitis B and C).5

Numerous epidemiological studies have documented the close relationship between mental and substance use disorders.6,7 The mechanisms behind this comorbidity are diverse and complex. They include, among others, those that are genetic8 and neurobiological,9 as well as psychosocial adversity.10 The order of the comorbidity may be from mental disorder to drugs11–13 or from drugs to mental disorder,14,15 but the possibility of a non-causal reciprocal relationship or simple coexistence has not been ruled out.16

Prevalences of depression in community samples are in the range of 2–5%,17 5–10% in primary care18,19 and 10–20% in hospitalised medical/surgical patients.20 The higher prevalence in hospital settings has been explained by neurobiological and psychosocial mechanisms that make patients with chronic diseases particularly vulnerable.21 In Colombia, the Estudio Nacional de Salud Mental [National Mental Health Study]22 showed that disorders secondary to substance abuse are the second leading cause of psychiatric illness in adult life, with a prevalence for any substance of 9.6%,23 with the use of legal substances, such as alcohol and cigarettes, the most common, followed by cannabis and cocaine.24

Addressing dual diagnosis in hospitalised patients is important because of their worse general medical and psychiatric prognosis, the greater degree of suffering for the patients and their families, and the greater use of health services.25 In different epidemiological studies, dual diagnosis is expressed in two ways: the prevalence of substance use disorders in patients with mental disorders; or the prevalence of mental disorders in patients with substance use disorders. The prevalences in these two populations can vary considerably. For example, in the study by Grant et al.,26 the prevalence of major depression in a group of patients with substance use disorder was 40%, while the prevalence of substance use disorder in a group of patients with major depression was 3.5%.

Despite the relationship between depression and substance use disorder, little has been studied about this comorbidity in populations of patients hospitalised in non-psychiatric settings. The purpose of this study was to determine the comorbidity between depression and substance use in adults hospitalised for non-psychiatric medical conditions.

MethodologyThis was a cross-sectional study that included 296 subjects. The sample was selected for convenience, from patients hospitalised for any medical or surgical condition. The patients were hospitalised in a public health centre offering highly complex care in the city of Medellín, Colombia. The inclusion criteria were: age from 18 to 65; first language Spanish; and being able to read and write. The exclusion criteria were: presence of delirium; cognitive impairment; mental illness as a reason for hospitalisation; and any other clinical condition that compromised the ability to give informed consent or answer the questions in the questionnaire.

The variables included were: age; gender; education; marital status; employment status; place of residence; and the questions on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and ASSIST 3.0 scales. The survey was applied by a healthcare worker and consisted of 22 questions. Two instruments were used: 1) the PHQ-9 questionnaire for the diagnosis of major depression, with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 89%, validated in Spanish,27 which consists of nine items that assess the presence of depressive symptoms (corresponding to the DSM-IV criteria) in the last two weeks; and 2) the ASSIST 3.0 Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO),28 which screens for 11 psychoactive substances; it is applied by a healthcare worker, with a sensitivity of 80%, a specificity of 89% and a cut-off point of 14.5 points. This scale determines a risk score for each substance and the risk is specified according to the cut-off points as low, moderate and high, with the intervention required for each of them: brief, moderate or intensive.

A pilot test was carried out on 10 people, determining the average time required by the participants to complete the survey and their understanding of the questionnaire questions. Descriptive analyses were performed of the sociodemographic variables and normality tests for age, obtaining summary and dispersion measures. Possible associations between the variables were explored considering a significance level of 5%. Prevalence ratios (PR) were calculated as a measure of the strength of association, with a 95% CI. The research project was approved by the University Ethics Committee and the ethics committee of the hospital where the patients were recruited. In addition, all participants were asked to give their informed consent. The information was analysed with the SPSS 21.0 software with an authorised user licence.

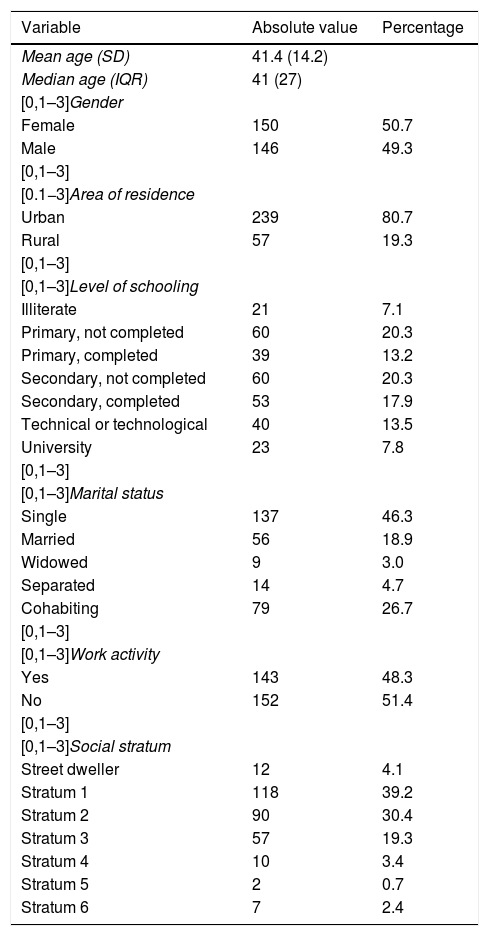

ResultsThe study included 296 hospitalised patients. Of these, 50.7% were female, the median age was 41 and the interquartile range was 27 years, 46.3% were single and 45.6% had a partner, 80.7% came from urban areas and 38.2% had completed secondary school (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | Absolute value | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 41.4 (14.2) | |

| Median age (IQR) | 41 (27) | |

| [0,1–3]Gender | ||

| Female | 150 | 50.7 |

| Male | 146 | 49.3 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0.1−3]Area of residence | ||

| Urban | 239 | 80.7 |

| Rural | 57 | 19.3 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Level of schooling | ||

| Illiterate | 21 | 7.1 |

| Primary, not completed | 60 | 20.3 |

| Primary, completed | 39 | 13.2 |

| Secondary, not completed | 60 | 20.3 |

| Secondary, completed | 53 | 17.9 |

| Technical or technological | 40 | 13.5 |

| University | 23 | 7.8 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Marital status | ||

| Single | 137 | 46.3 |

| Married | 56 | 18.9 |

| Widowed | 9 | 3.0 |

| Separated | 14 | 4.7 |

| Cohabiting | 79 | 26.7 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Work activity | ||

| Yes | 143 | 48.3 |

| No | 152 | 51.4 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Social stratum | ||

| Street dweller | 12 | 4.1 |

| Stratum 1 | 118 | 39.2 |

| Stratum 2 | 90 | 30.4 |

| Stratum 3 | 57 | 19.3 |

| Stratum 4 | 10 | 3.4 |

| Stratum 5 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Stratum 6 | 7 | 2.4 |

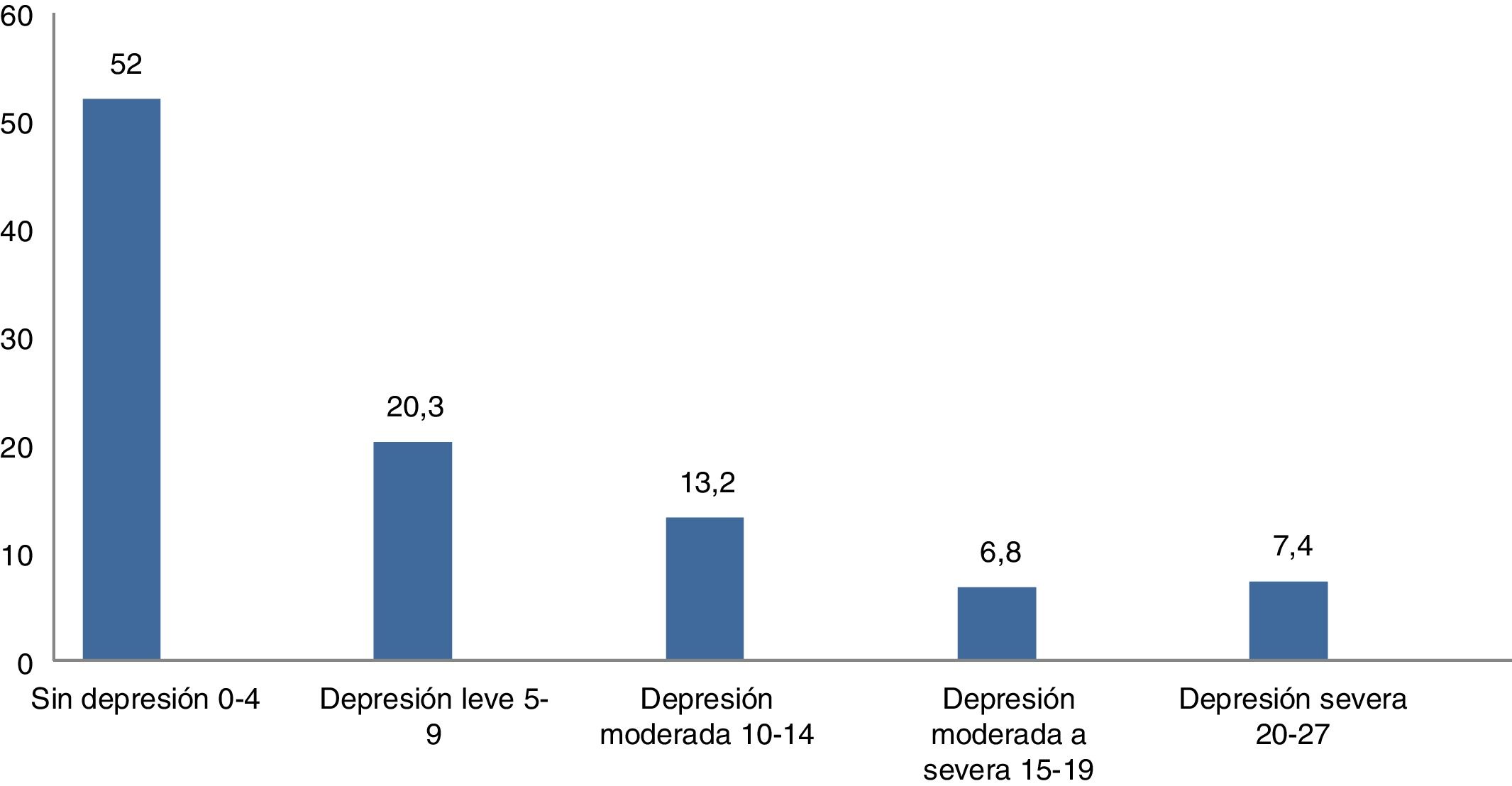

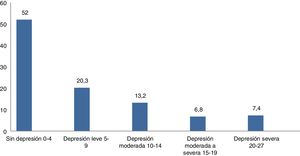

According to the PHQ-9 scale, we found that 27.4% of those surveyed had clinically significant depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) and 14.2% had moderate to severe symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 15) (Fig. 1).

Regarding the time these patients had been suffering the depressive symptoms, we found that 17.8% had been suffering them for less than a week, 32.4% less than a month, 22.1% less than six months, 9.2% less than one year, 9.2% less than five years, 2.1% less than 10 years and 7% more than 10 years.

By gender, 43.2% of the males had depressive symptoms compared to 52.7% of the females. Females were also more likely to have moderate and severe symptoms (18.7%) compared to males (9.6%).

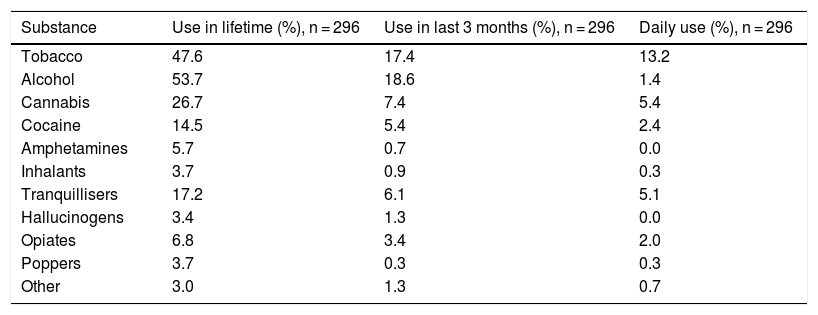

Prevalence and frequency of substance useThe highest lifetime prevalence found was for alcohol (53.7%), followed by cigarettes (47.6%), cannabis (26.7%), tranquillisers (17.2%) and cocaine (14.5%). The least frequent use of substances was for poppers (3.7%) and other unspecified substances of abuse (3.0%). Regarding the prevalence in the last three months, the highest rate was for legal substances, such as alcohol and tobacco (Table 2).

Prevalence of lifetime, last three months and daily substance use in hospitalised patients.

| Substance | Use in lifetime (%), n = 296 | Use in last 3 months (%), n = 296 | Daily use (%), n = 296 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | 47.6 | 17.4 | 13.2 |

| Alcohol | 53.7 | 18.6 | 1.4 |

| Cannabis | 26.7 | 7.4 | 5.4 |

| Cocaine | 14.5 | 5.4 | 2.4 |

| Amphetamines | 5.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| Inhalants | 3.7 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Tranquillisers | 17.2 | 6.1 | 5.1 |

| Hallucinogens | 3.4 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| Opiates | 6.8 | 3.4 | 2.0 |

| Poppers | 3.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Other | 3.0 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

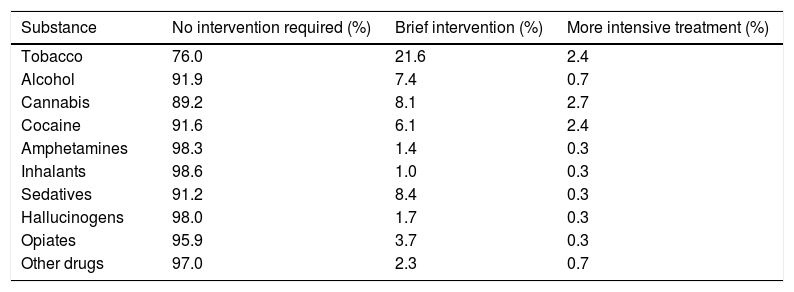

Over the last three months, the highest rate was for alcohol (18.6%) and tobacco (17.4%), compared to daily use, where the highest prevalence was for tobacco (13.2%) and cannabis (5.4%) (Table 2). According to the ASSIST score, we determined that the patient group in which a greater proportion required intervention for substance use were tobacco users (24.0%), followed by cannabis users (10.8%) (Table 3).

Intervention required according to substance and score in the ASSIST 3.0 test.

| Substance | No intervention required (%) | Brief intervention (%) | More intensive treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | 76.0 | 21.6 | 2.4 |

| Alcohol | 91.9 | 7.4 | 0.7 |

| Cannabis | 89.2 | 8.1 | 2.7 |

| Cocaine | 91.6 | 6.1 | 2.4 |

| Amphetamines | 98.3 | 1.4 | 0.3 |

| Inhalants | 98.6 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| Sedatives | 91.2 | 8.4 | 0.3 |

| Hallucinogens | 98.0 | 1.7 | 0.3 |

| Opiates | 95.9 | 3.7 | 0.3 |

| Other drugs | 97.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

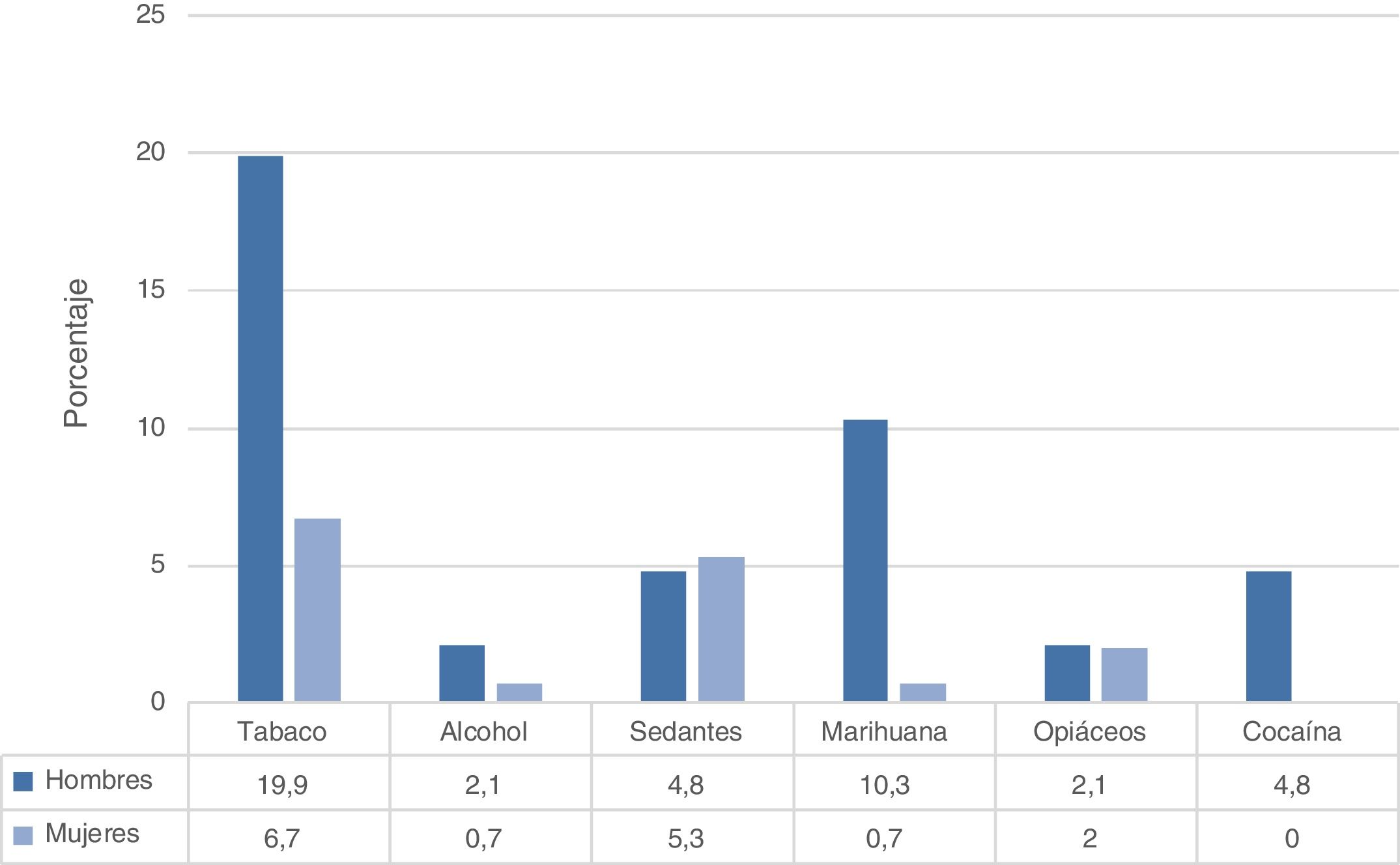

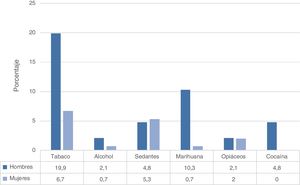

When daily substance use was compared by gender, we found that tobacco was the substance most used in males and females, followed by cannabis in males and sedatives in females (Fig. 2).

A total of 22.6% of males and 12.7% of females stated that in the last three months a friend, relative or acquaintance had expressed concern about their substance use. The substances patients had made greatest efforts to reduce or control their consumption of were: tobacco, for both males and females (25.4% and 10.7% respectively); followed by alcohol (17.1% and 4.0%); cannabis (15.0% and 1.4%); and cocaine (11.0% and 0.7%).

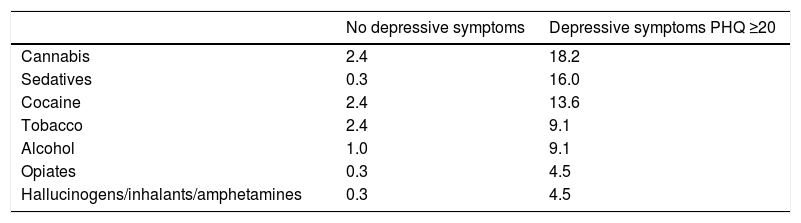

Comorbidity between depressive symptoms and substance useA significant association was found between severe depressive symptoms PHQ-9 ≥ 20 and substance use that required intensive intervention (ASSIST 3.0 > 26). Compared to those without depressive symptoms, patients with severe depressive symptoms had a 27-fold higher risk of alcohol use (PR 27.30; 95% CI, 2.37–314.16; p = 0.01), 15-fold higher risk for cannabis (PR 15.00; 95% CI, 3.46–64.96; p = 0.001) and 10-fold higher for cocaine (PR 10.65; 95% CI, 2.23–51.10; p = 0.01).

We compared the proportion of patients requiring substance use intervention when they did not have depressive symptoms and when symptoms were severe (PHQ-9 ≥ 20), and found that treatment for substance dependence was required to a greater extent when depressive symptoms were severe (Table 4).

Proportion of patients requiring intervention for substance use according to severe depressive symptoms.

| No depressive symptoms | Depressive symptoms PHQ ≥20 | |

|---|---|---|

| Cannabis | 2.4 | 18.2 |

| Sedatives | 0.3 | 16.0 |

| Cocaine | 2.4 | 13.6 |

| Tobacco | 2.4 | 9.1 |

| Alcohol | 1.0 | 9.1 |

| Opiates | 0.3 | 4.5 |

| Hallucinogens/inhalants/amphetamines | 0.3 | 4.5 |

In terms of the onset of symptoms, we found that females developed depressive symptoms first (95.0% vs 5.0%), while in males, substance use came first (61.0% vs 39.0%).

We looked for possible associations between sociodemographic variables and patients with simultaneous presence of severe depressive symptoms and substance use, and found an association with having less than basic secondary education (PR 1.84; 95% CI, 1.15–2.95; p = 0.01).

DiscussionThis study explored the comorbidity of clinically significant depressive symptoms and substance use in patients hospitalised for non-psychiatric medical illnesses. Among the most significant findings was that alcohol was the most widely used legal substance, followed by cannabis, hypnotics/sedatives and cocaine.

Additionally, a significant association was identified between severe depressive symptoms and problematic use of alcohol, cannabis and cocaine.

What is unique about these results is that they come from patients hospitalised for non-psychiatric clinical conditions, termed “medically ill patients”, in whom the presence of dual pathology was sought (clinically significant depressive symptoms and use of any of a list of 11 substances). Dual pathology has been described as a risk factor for a worse prognosis of underlying medical diseases.29,30

Our findings correlate with those from the WHO study and the Colombian Drug Observatory.31 The First Medellín Mental Health Study 2011–201232 found a prevalence for depression in the last 30 days of 1.2% (1.6% for females and 0.6% for males), with a lifetime prevalence of 9.9% (5.6% males and 12.4% females). After comparison with the results obtained in our study, the conclusion from these prevalences is that one in every four patients has clinically significant depressive symptoms, while in the general population of Medellín, depression occurs in one in every 10 people.

The importance of talking about dual pathology in the hospital population with non-psychiatric diseases lies in the increased risk and the need for mental health intervention in these patients, which very often goes unnoticed by healthcare teams.

Available evidence shows that substance use disorders are more prevalent in people with severe mental disorders.33 A recent meta-analysis reported that people with alcohol use disorder had a 3.1-fold higher risk of developing depression compared to people without the disorder.34 In our study, a high degree of comorbidity was found between alcohol and depressive symptoms, with the association being significant.

The Medellín Mental Health study32 found alcohol dependence over the last 12 months in 4.09% of males and 0.82% of females, while our study found that 8.1% of patients hospitalised for non-psychiatric conditions required intervention for their alcohol use. This gives us an idea of the magnitude of the problem in these patients.35 In view of the fact that alcohol is associated with more than 200 health conditions identified in the ICD-10,35 and 5.9% of deaths and 5.1% of disability due to illness or trauma worldwide in 2012 were attributable to alcohol use, generating 139 million disability-adjusted life years (DALY), this situation could have serious consequences for physical health.36

The relationship between cigarette smoking and depression shows that 59% of patients with major depressive disorder and 60% of those with dysthymia are lifelong smokers37; smokers with depression smoke more and have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality than non-depressed people.38 This study found no association between depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking, although one in every four patients who smoked required clinical intervention.

Cocaine and cannabis use is on the increase in Colombia.39 This could be because of greater availability of illicit drugs in the community.40 However, it is possible that the high comorbidity between depressive symptoms and daily use of cannabis and cocaine may also be a contributing factor.

Among the so-called illegal substances, cannabis is not only the most widely used by people with depressive disorders,41 but, according to a large study by Lev-Ran et al.,42 which included 43,070 people over 18 years of age, people with a mental disorder in the past 12 months account for 72% of all cannabis users.

Cocaine use has been associated with significant neurological and cardiovascular risk.43 It has been estimated that approximately 30% of people with major depressive disorder suffer from cocaine use disorder in their lifetime and 35% of cocaine abusers suffer from depressive disorder in their lifetime,44 which could in part be explained by them sharing a similar genetic vulnerability.45 In a more recent study of 115 people addicted to cocaine use, López and Becoña46 found the prevalence of depression to be 24.3%. These reported prevalences are lower than in our study, although the populations are not comparable.

According to the Madrid study on the prevalence and characteristics of patients with dual pathology, the most common characteristics in these patients are: male; low socioeconomic status47; young; single; lower educational level; and poor employment status.48 These factors were observed in our study, where three out of four patients belonged to low socioeconomic strata, half were unemployed and the highest rates of substance use were in males.

Finally, the findings of this study should be interpreted taking the following limitations into account. First of all, with a descriptive cross-sectional study, it is not possible to establish causal relationships. Secondly, depressive and substance abuse disorders were assessed using structured scales and not by direct psychiatrist assessment, which is considered the gold standard for these diagnoses. Thirdly, patient responses may be affected by memory biases, which could be reflected in lower-than-actual prevalences. Fourthly, it is possible that the participants did not give reliable information on sensitive subjects such as those dealt with in this survey, although the interviewers were trained to show empathy, be non-judgemental and guarantee anonymity and privacy concerning the information provided. Despite these limitations, this research provides valuable information about the comorbidity of depressive symptoms and substance use in patients hospitalised for non-psychiatric medical conditions. In fifth place, no information was collected to determine whether or not the patient was receiving medical care for depressive symptoms and substance use. Sixth and last, the scale used to screen depression, the PHQ-9, includes somatic symptoms, which in medically ill patients can be a bias factor. However, the performance of this scale has been shown to be similar to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), frequently used in studies of depression in patients with non-psychiatric illnesses.48

ConclusionsThis study found a high level of comorbidity between clinically significant depressive symptoms and substance use in patients hospitalised for non-psychiatric medical conditions. Healthcare teams need adequate training to be able to identify and appropriately treat dual pathology in non-psychiatric clinical settings. Moreover, further studies are needed to provide more information on this important health issue.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Campuzano-Cortina C, Feijoó-Fonnegra LM, Manzur-Pineda K, Palacio-Muñoz M, Rendón-Fonnegra J, Montoya L, et al. Comorbilidad entre síntomas depresivos y consumo de sustancias en pacientes hospitalizados por enfermedades no psiquiátricas. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:130–137.