Cultural psychiatry evaluates manifestations, symptoms of emotional distress and mental disorders in diverse cultural contexts; it also addresses social problems such as poverty, violence, inequalities between groups or social classes.

ObjectiveTo present a narrative review of the most relevant cultural aspects in the context of clinical practice in psychiatry and to suggest some alternatives to improve the cultural competence of health care professionals.

MethodA narrative review was carried out of the most relevant articles in the area.

ResultsUsually, the cultural argument is used to explain differences in observed prevalences in some mental disorders according to gender and geographical location. Cultural differences modify the expression of emotional distress and this can reduce the accuracy and affect the reliability and validity of the current diagnostic classification used in psychiatry. The American Psychiatric Association, in the most recent classification, revised cultural syndromes but only included a limited number of situations. Consequently, medical education and psychiatry must respond to diverse populations and provide quality care through the development of trans-cultural competence in the curriculum.

ConclusionsIt should be considered that cultural differences modify the expression of distress and thereby undermine the validity and reliability for diagnoses in distinct cultural contexts. In an increasingly globalised world, future classifications may completely omit ‘cultural syndromes’.

La psiquiatría cultural evalúa las manifestaciones, los síntomas de sufrimiento emocional o los trastornos mentales en los distintos contextos culturales; asimismo, aborda problemas sociales como la pobreza, la violencia y las desigualdades entre grupos o clases sociales.

ObjetivoPresentar una revisión narrativa de los aspectos culturales más relevantes en el contexto de la práctica clínica en psiquiatría y proponer algunas alternativas para mejorar la competencia cultural de los profesionales de la salud.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo una revisión narrativa de los artículos más relevantes en el área.

ResultadosHabitualmente se utiliza la perspectiva cultural para explicar diferencias en las prevalencias que se observan en algunos trastornos mentales según el sexo y la localización geográfica. Las diferencias culturales modifican la expresión de distress o sufrimiento emocional, y esto puede reducir la precisión y afectar a la confiabilidad de las clasificaciones y la validez de los diagnósticos actuales usados en psiquiatría. La Asociación Psiquiátrica Americana, en la clasificación más reciente, revisó los trastornos asociados con la cultura pero solo incluyó un reducido número de situaciones. La formación médica y la psiquiatría deben responder a las necesidades de comunidades diversas y proporcionar un cuidado de calidad mediante el desarrollo de competencias transculturales en los currículos.

ConclusionesSe debe considerar que las diferencias culturales modifican la expresión de distress y con ello se menoscaba la validez y la confiabilidad de los diagnósticos hegemónicos en distintos contextos culturales. En un mundo cada vez más globalizado, es posible que futuras clasificaciones diagnósticas omitan los «síndromes culturales».

Cultural psychiatry concerns mental disorders and how they vary according to the group in which they occur, and interprets symptoms and emotional distress in different contexts.1 At the same time, cultural psychiatry not only addresses symptoms, but also beliefs about the causes, treatments and ways of coping with mental disorders in a particular group of people. However, the adjective “cultural” has not always been applied to this area of psychiatry, which was termed “exotic psychiatry” and “tropical psychiatry” in its beginnings. Subsequently, it was called ethnopsychiatry and social psychiatry and later, comparative psychiatry and transcultural psychiatry (cross-, trans-), according to the underlying or hegemonic ideological perspective of the historical moment.2–4 The changes in the name respond to the general idea of giving importance to and recognising the importance of the local context on health.1–4

Culture is not only a pattern of intrinsic, homogeneous and fixed characteristics of a person or group, but involves a continuous, permanent and flexible process of transmission and use of knowledge that depends on the dynamics that occur within groups of people, and the resulting interactions between these people and communities with formal and informal social or political institutions.1

In the field of health, with the inclusion of psychiatry, the concept of “culture” is used to explain the different ways in which people interpret and deal with (or treat) the same medical conditions according to a particular context.5,6 Culture permeates mental health in at least two different ways. In the first, people use culturally specific explanatory models to think and talk about and manage mental health issues, and to explain the causes of mental illnesses and the type of treatments that these people can receive. In Colombia, both in a study published by León and Micklin in 1971, and in the research by De Taborda et al in 1976, these explanations were based on popular beliefs, with a predominance of those with an organic basis, followed by a wide range of causalities (emotional, psychosocial, sociocultural, magical and religious).7,8 In keeping with these definitions for the “aetiology”, back in those years it was already considered that the treatments provided to patients should be those with a “physical” basis, such as drugs and somatic therapies.7 The second way culture permeates mental health is that cultural habits and practices can encourage or modify behaviour in day-to-day life, like, for example, the pattern of alcohol use or use of other substances susceptible to abuse that lead to specific clinical “disorders” or alter the course of other underlying or comorbid mental disorders.9 However, cultural psychiatry has not only focused on mental health problems, but has also included the study of social problems such as poverty, violence and inequalities between groups or social classes.1

The aim of this article is to reflect on the attention given by cultural psychiatry to cultural syndromes within the framework of the publication of the DSM-5, and to discuss the challenges for Colombian healthcare professionals in studying these syndromes.

Development of the subjectThe DSM-5 presents three new tautological definitions to better explain the so-called culture-related mental disorders that already appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, revised fourth edition (DSM-IV-TR)10: a) idiomatic expressions of distress; b) perceived causes or cultural explanations of mental disorders; and c) cultural syndromes.11 This version of the manual also includes a Cultural Formulation Interview with 16 questions that cover the cultural definition of the problem, cultural factors involved, cultural factors that may affect treatment and coping, and models for requesting help in previous episodes.10

Regarding cultural syndromes, the discussion revolves around the following issues: a) the very conception of the syndromes; b) the process surrounding the choice of syndromes currently included; c) study and research; and d) the visibility of Latin American cultural syndromes.

The issue of the very conception of syndromes is centred on an old discussion about whether these cultural syndromes are autonomous entities or simply clinical variants of entities already conventionally recognised. That discussion involves the idea that what is considered “normal” or “pathological” in a certain group is a result of immediate social judgement, and that connotation can obviously vary between different cultures. What is relevant for an ethnic group has to do with the adaptation and survival practices that are peculiar to a particular human group. In the cultural perspective, those who agree with this view are considered relativistic, and those who consider mental disorders as a set of symptoms that correspond to general cultural patterns are called universalists.12 These two visions are directly involved in cultural syndromes; the importance of cultural aspects in the diagnostic process is highlighted and it is stressed that the limits for “normal” and “dysfunctional” change according to culture for specific behaviours.13

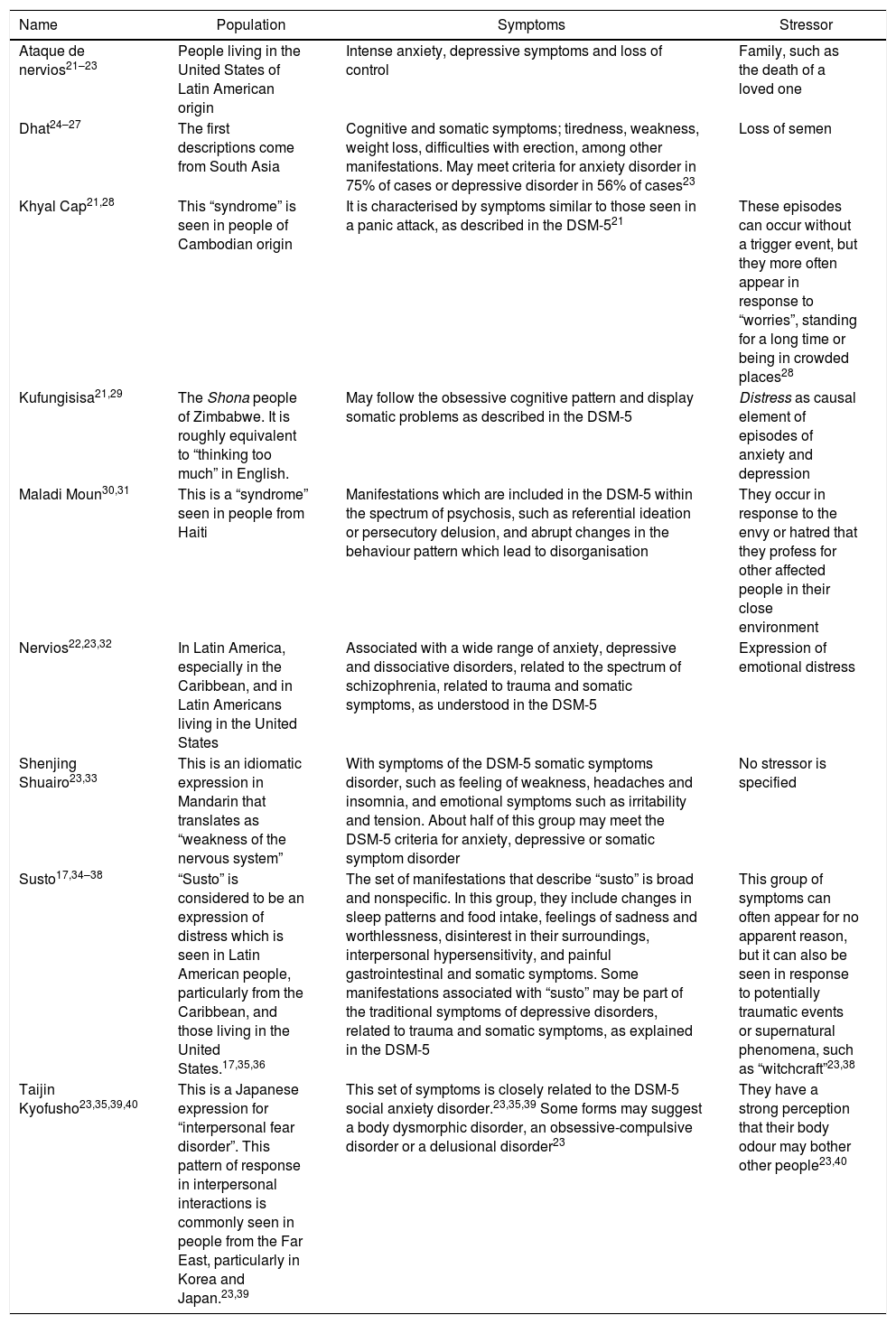

In relation to the debate on the choice of the syndromes currently included, the number of syndromes was much higher in the previous version of the DSM than in the current version. Now only eight disorders are featured (Table 1). The question is: what were the criteria used for only including eight disorders? The answer lies in a tacit and emphatic focus on certain minorities or ethnic groups as the focus of cultural research. For example, Afro-descendant minorities and migrants in the United States have been given priority. This selection criterion is detrimental to the evaluation of certain groups over others in the clinical assessment in general.14 Moreover, in this version of the manual, external validity factors such as aetiology, laboratory markers, response to treatment and results were included, and only syndromes that met the criteria mentioned were left out, due to the difficulty of making the assessment with the current classification systems.15

Cultural syndromes included in the DSM-5.

| Name | Population | Symptoms | Stressor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ataque de nervios21–23 | People living in the United States of Latin American origin | Intense anxiety, depressive symptoms and loss of control | Family, such as the death of a loved one |

| Dhat24–27 | The first descriptions come from South Asia | Cognitive and somatic symptoms; tiredness, weakness, weight loss, difficulties with erection, among other manifestations. May meet criteria for anxiety disorder in 75% of cases or depressive disorder in 56% of cases23 | Loss of semen |

| Khyal Cap21,28 | This “syndrome” is seen in people of Cambodian origin | It is characterised by symptoms similar to those seen in a panic attack, as described in the DSM-521 | These episodes can occur without a trigger event, but they more often appear in response to “worries”, standing for a long time or being in crowded places28 |

| Kufungisisa21,29 | The Shona people of Zimbabwe. It is roughly equivalent to “thinking too much” in English. | May follow the obsessive cognitive pattern and display somatic problems as described in the DSM-5 | Distress as causal element of episodes of anxiety and depression |

| Maladi Moun30,31 | This is a “syndrome” seen in people from Haiti | Manifestations which are included in the DSM-5 within the spectrum of psychosis, such as referential ideation or persecutory delusion, and abrupt changes in the behaviour pattern which lead to disorganisation | They occur in response to the envy or hatred that they profess for other affected people in their close environment |

| Nervios22,23,32 | In Latin America, especially in the Caribbean, and in Latin Americans living in the United States | Associated with a wide range of anxiety, depressive and dissociative disorders, related to the spectrum of schizophrenia, related to trauma and somatic symptoms, as understood in the DSM-5 | Expression of emotional distress |

| Shenjing Shuairo23,33 | This is an idiomatic expression in Mandarin that translates as “weakness of the nervous system” | With symptoms of the DSM-5 somatic symptoms disorder, such as feeling of weakness, headaches and insomnia, and emotional symptoms such as irritability and tension. About half of this group may meet the DSM-5 criteria for anxiety, depressive or somatic symptom disorder | No stressor is specified |

| Susto17,34–38 | “Susto” is considered to be an expression of distress which is seen in Latin American people, particularly from the Caribbean, and those living in the United States.17,35,36 | The set of manifestations that describe “susto” is broad and nonspecific. In this group, they include changes in sleep patterns and food intake, feelings of sadness and worthlessness, disinterest in their surroundings, interpersonal hypersensitivity, and painful gastrointestinal and somatic symptoms. Some manifestations associated with “susto” may be part of the traditional symptoms of depressive disorders, related to trauma and somatic symptoms, as explained in the DSM-5 | This group of symptoms can often appear for no apparent reason, but it can also be seen in response to potentially traumatic events or supernatural phenomena, such as “witchcraft”23,38 |

| Taijin Kyofusho23,35,39,40 | This is a Japanese expression for “interpersonal fear disorder”. This pattern of response in interpersonal interactions is commonly seen in people from the Far East, particularly in Korea and Japan.23,39 | This set of symptoms is closely related to the DSM-5 social anxiety disorder.23,35,39 Some forms may suggest a body dysmorphic disorder, an obsessive-compulsive disorder or a delusional disorder23 | They have a strong perception that their body odour may bother other people23,40 |

Similarly, the inclusion of some syndromes responds purely to the interests in classifications and diagnoses from the hegemonic Western countries. This is a form of neocolonialism, favouring the interests derived from the medical-industrial and financial establishment in generating profits from the introduction of medicines and services for conditions that are not diseases or disorders per se, but simply an expression of emotional distress in response to the sociocultural environment.16–19 This process is not exclusive to the specialist area of psychiatry, but to all of medicine as a profession, where doctors stopped being independent professionals and became employees (workers), absorbed into healthcare systems with their own particular interests, from which the pathologising of cultural syndromes has derived, along with the transformation of ethnic groups and communities into a set of patients.20

The cultural argument is often used to explain the differences in prevalences observed in some mental disorders according to gender and different geographical locations without further analysis. However, it is high time we began to think a little beyond that.3 It is important to consider that cultural differences modify or moderate the expression of distress or emotional suffering in different cultural contexts, and this can reduce the precision and affect the reliability of classifications and the validity of diagnoses in psychiatry.41,42 Even more so if “classification” is understood as the grouping or categorisation of symptoms and “diagnosis” as the possible causes or mechanisms underlying each set of symptoms to which is applied the name of a particular mental disorder.43

The debate on study and research leads to the analysis of Latin American output with respect to cultural syndromes. It is evident that it is still incipient, possibly for three reasons: a) the limited allocation of resources for research on these issues in the different countries; Brazil, Mexico and Chile are those with the highest output in this field, and in 1974 in Colombia, León published a study involving several families on El duende44; b) research focuses on interests that favour the agenda of instrument validation and epidemiological studies, rather than studies that make cultural comparisons; and c) heterogeneous indexing of publications in databases (for example, the term culture-bound is not available in MEDLINE, but estudios transculturales [cross-cultural studies] does appear, and these studies are excluded the descriptor “culture” is used).45

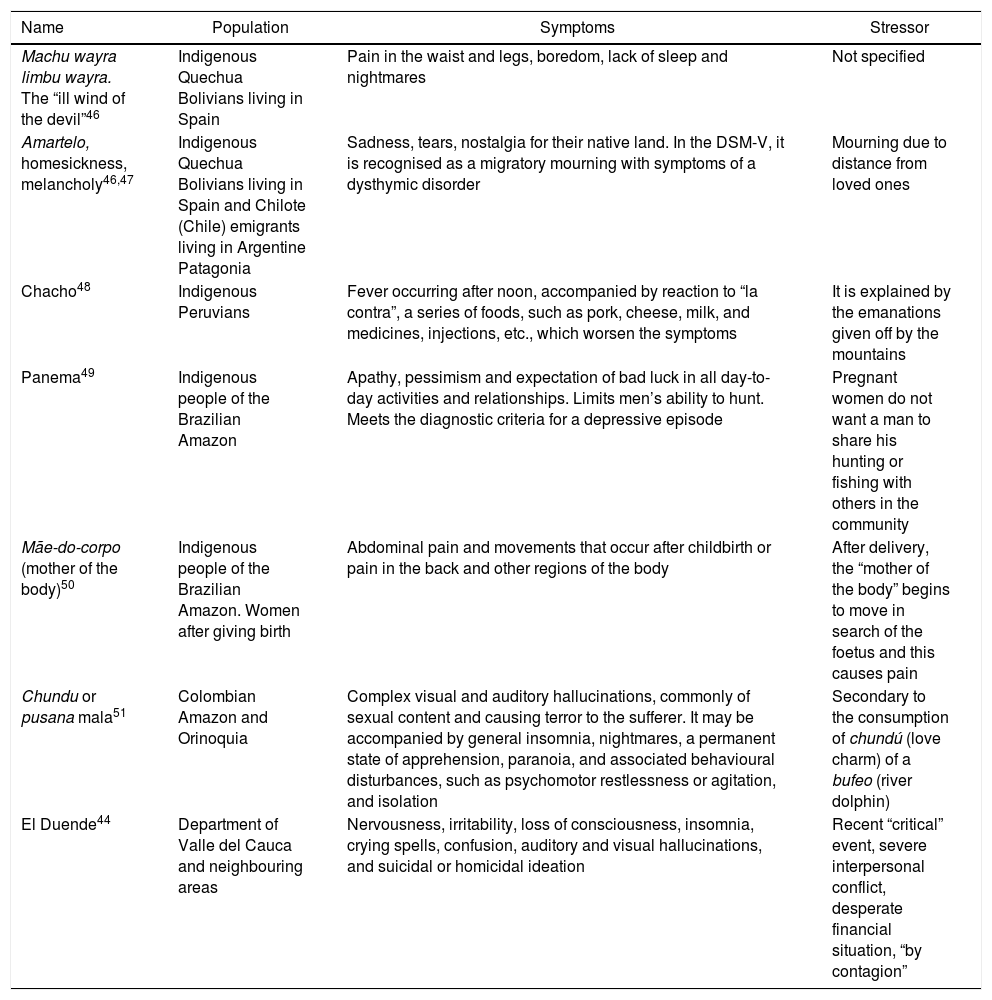

In the final debate on the visibility of Latin American cultural syndromes, we need to go back to what we said about the limited amount of research. The lack of uniquely Latin American syndromes in the DSM-V is clear, and those included are far from being representative of the wide cultural diversity across the continent and even less so of that in Colombia. For that reason, in Table 2 we show a summary of some identified in the EBSCO and Proquest databases using the keywords “culture-bound syndrome” and “Latino”.

Syndromes associated with the culture in Latin America.

| Name | Population | Symptoms | Stressor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machu wayra limbu wayra. The “ill wind of the devil”46 | Indigenous Quechua Bolivians living in Spain | Pain in the waist and legs, boredom, lack of sleep and nightmares | Not specified |

| Amartelo, homesickness, melancholy46,47 | Indigenous Quechua Bolivians living in Spain and Chilote (Chile) emigrants living in Argentine Patagonia | Sadness, tears, nostalgia for their native land. In the DSM-V, it is recognised as a migratory mourning with symptoms of a dysthymic disorder | Mourning due to distance from loved ones |

| Chacho48 | Indigenous Peruvians | Fever occurring after noon, accompanied by reaction to “la contra”, a series of foods, such as pork, cheese, milk, and medicines, injections, etc., which worsen the symptoms | It is explained by the emanations given off by the mountains |

| Panema49 | Indigenous people of the Brazilian Amazon | Apathy, pessimism and expectation of bad luck in all day-to-day activities and relationships. Limits men’s ability to hunt. Meets the diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode | Pregnant women do not want a man to share his hunting or fishing with others in the community |

| Mãe-do-corpo (mother of the body)50 | Indigenous people of the Brazilian Amazon. Women after giving birth | Abdominal pain and movements that occur after childbirth or pain in the back and other regions of the body | After delivery, the “mother of the body” begins to move in search of the foetus and this causes pain |

| Chundu or pusana mala51 | Colombian Amazon and Orinoquia | Complex visual and auditory hallucinations, commonly of sexual content and causing terror to the sufferer. It may be accompanied by general insomnia, nightmares, a permanent state of apprehension, paranoia, and associated behavioural disturbances, such as psychomotor restlessness or agitation, and isolation | Secondary to the consumption of chundú (love charm) of a bufeo (river dolphin) |

| El Duende44 | Department of Valle del Cauca and neighbouring areas | Nervousness, irritability, loss of consciousness, insomnia, crying spells, confusion, auditory and visual hallucinations, and suicidal or homicidal ideation | Recent “critical” event, severe interpersonal conflict, desperate financial situation, “by contagion” |

Considering Colombia’s multi-ethnic and multicultural nature, and great regional differences, it is important to recognise the main challenges facing Colombian healthcare professionals in their clinical practice.

Challenge 1. Recognise that cultural factors pervade clinical practiceCultural components or factors are not exclusive to the clinical practice of psychiatry. They are present in all areas of medicine.3 The impact of cultural factors is linked not only to the assessment, but also to the interpretation, of mental disorders and physical conditions in all five continents.6,52,53 It is important to be aware that the work of mental health practitioners concerns both the identification of new syndromes and the explanations provided by the population of the causes and interpretations of mental disorders.4,41

Challenge 2. Identify how culture affects confidence in recommended therapeutic actions and follow-upCulture plays a decisive role in the seeking of formal and informal help.4,41,54 In view of the potential impact of the therapeutic actions of healthcare professionals, cultural psychiatry and future psychiatrists need to develop certain cultural competencies to help them recognise new syndromes and assess the boundary between culture and “psychopathology/mental disorder”, in addition to training in clinical judgement. The assessment therefore involves a high degree of subjectivity, often culturally nuanced.55

Challenge 3. Assess the extent to which these sociocultural factors explain how symptoms are experienced and how they are communicatedAs a group, the sociocultural factors are related to the social significance attached to meeting the criteria for a mental disorder.41 At the same time, the cultural context explains much of the stigma-discrimination complex associated with major mental disorders.56 Moreover, professionals must be attentive to the additional explanations that culture provides for the disparities observed in the health-disease-care process of different groups or populations when exclusively biological and genetic factors do not satisfy the systematic and structured observations of the completely positivist approaches.3,57

Challenge 4. Analyse the impact of cultural differences on the expression of distressHealthcare professionals must be very aware that differences between cultures affect the accuracy of classifying these informal expressions into formal symptoms and, as a result, undermine the validity and reliability of diagnoses in different cultural contexts.41,42 For example, healthcare professionals must avoid confronting, arguing or correcting the patient or making them feel they are giving the wrong answers. This promotes a less tense atmosphere and helps avoid any negative impact caused by the perspective of the practitioner, who in some ways could be seen as an outsider (who does not know the culture of the other: etic perspective), and who must try to understand the cultural perspective of the patient (native person: emic perspective).6

Challenge 5. Promote explicit actions to combat ethnocentric bias and racial stereotypesPsychiatrists must nowadays address the basic need for unbiased practice. Bias is present in everyday practice. For example, in the United States and the United Kingdom, non-Caucasian patients, particularly African Americans or people of African descent, receive more physical treatments, more antipsychotics than antidepressants, and less psychotherapy.58,59 In other words, a diagnosis of schizophrenia is more likely than that of a depressive disorder, just because of the cultural difference between the healthcare professional and the service user.59,60

There is a need for clinicians to recognise and identify symptoms described in the classifications among the clinical manifestations of the disorders. However, to help the patient, and in an attempt to span the whole variety and complexity of human suffering, always nuanced by culture, practitioners also need to encourage them to speak freely about the cognitive and emotional experiences that led them to seek help.61–64

Challenge 6. Investigate cultural aspects going beyond a mere study of minorities and disadvantaged groupsNaturally, more research is needed in this area with the aim that cultural psychiatry extends beyond the study of groups called minorities, immigrants or more disadvantaged groups.65,66 It is important to have evidence that corroborates the validity and reliability of the observations collected to date, both from the perspective of external observers (etic, from the anthropological perspective) and internal observers (emic), and that these are incorporated into care processes and help reduce cultural barriers to accessing health services.67–69

Colombia is a culturally diverse and multi-ethnic country. Cultural relevance must therefore be a constant both in the training of human talent in health and in the minds of healthcare workers practising their profession. The differences found in the recognition of emotions in Colombian regions are an interesting finding in this regard, as shown in the 2015 National Mental Health Survey.70

ConclusionsIt is clear that cultural psychiatry has a great deal to learn in terms of work with the different communities here in Colombia, whether indigenous, Raizal or migrants, and there continue to be no clear guidelines in terms of setting up funding for empirical research on Colombian cultural syndromes. A first task is to start using the Cultural Formulation Interview. Its systematic application to patients from different social or ethnic-cultural segments of society in Colombia could be a new way of incorporating culture into daily work, and identifying cultural idioms of distress or causal attributions of unquestionable psychotherapeutic and preventive value.

Reporting of symptoms related to mental disorders varies according to the cultural context; consequently, the cultural context can affect the observed prevalence of mental disorders. Culture plays an important role both in the seeking of help and in treatment when it comes to mental disorders. We need to take into account the cultural varieties that exist in the Colombian context and incorporate them into the health training of human talent and into the practices of our healthcare professionals.

FundingThe Universidad del Magdalena [University of Magdalena], Santa Marta, funded the participation of Adalberto Campo-Arias and Mónica Reyes-Rojas and the Instituto de Investigación del Comportamiento Humano [Institute for Research in Human Behaviour], Bogotá, Colombia, funded Edwin Herazo’s contribution as author.

Conflict of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Campo-Arias A, Herazo E, Reyes-Rojas M. Psiquiatría cultural: más allá del DSM-5. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:138–145.