Information about the frequency of zoophilic behaviour in the general population is scarce.

ObjectiveTo review cases, case series and prevalence studies of zoophilia in adults in the general population.

MethodsA review of publications was carried out in MEDLINE via PubMed, Scopus and the Biblioteca Virtual en Salud [Virtual Health Library] ranging from January 2000 to December 2017.

ResultsThirteen papers were reviewed (ten case reports, two case series and one cross-sectional study). Twelve patients were described, the case series totalled 1,556 people and the cross-sectional study included 1,015 participants and reported a prevalence of zoophilic behaviour of 2%.

ConclusionsInformation on the prevalence of zoophilic behaviour in the general population is limited. The Internet will probably be a valuable tool for further investigating these behaviours in coming years.

El conocimiento de la frecuencia de comportamientos zoofílicos en la población general es escaso.

ObjetivoRevisar casos, series de casos y estudios de prevalencia de zoofilia en adultos de la población general.

MétodosSe realizó una revisión en las bases de datos de MEDLINE, a través de PubMed, Scopus y la Biblioteca Virtual en Salud de publicaciones desde enero de 2000 hasta diciembre de 2017.

ResultadosSe revisaron 13 trabajos (10 informes de casos, 2 series de casos y 1 estudio transversal). Entre los casos se describió a 12 pacientes; las series de casos sumaron a 1.556 personas y el estudio transversal incluyó a 1.015 participantes e informó de una prevalencia de comportamientos zoofílicos del 2%.

ConclusionesEs escasa la información sobre la prevalencia de comportamientos zoofílicos en la población general. Es probable que internet permita investigar mejor estos comportamientos en los próximos años.

The term paraphilia was first used by Stekel in 1930 and popularised by Money in the seventies.1 Paraphilia has been used without pejorative connotations from the third version of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) until its most recent version, DSM-5.2,3 The term was introduced to replace the expression “perversion”, which had taken on derogatory and almost always criminal popular connotations, in order for paraphilias to be considered mental disorders.2,4

In the current DSM-5, paraphilia is defined as “any intense and persistent sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physiologically mature, consenting human partners”.2 This in itself does not imply a mental disorder.4–6 These sexual behaviours (paraphilias) are referred to as “paraphilic disorder”, “if the fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviours cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning”. In other words, they are understood as mental disorders.2 It is not always easy to accurately make this distinction.7

Wright8 maintains that the distinction between paraphilias and paraphilic disorders is a step towards depathologising uncommon sexual behaviours. However, a number of authors, including Fedoroff et al.4 and Echeburúa et al.,5 argue that this not only implies pathologisation (medicalisation or psychiatrisation), but also upholds the stigma-discrimination complex associated with heterodox sexual interests or behaviours. In turn, Hamilton9 maintains that the aim of this process is to give the connotation of mental disorder to some clearly criminal behaviours, thereby leaving the healthcare system with problems that should be dealt with by the justice systems.6,10 Without a doubt, these perspectives revive the long-standing controversy in psychiatry around the distinction between mental disorder and criminal behaviour.11

The paraphilic disorders category includes voyeuristic disorder, exhibitionistic disorder, frotteuristic disorder, sexual masochism disorder, sexual sadism disorder, paedophilic disorder, fetishistic disorder, other specified paraphilic disorder and unspecified paraphilic disorder.2

Zoophilic behaviours, or “zoophilia”, can be defined as “recurrent and intense sexual arousal” involving animals, and is therefore included in the “other specified paraphilic disorder” diagnosis if it is associated with significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning and has been present for at least six months.2

The diagnosis of zoophilia and other paraphilias is not free from controversy, as it implies the medicalisation, pathologisation, and in some cases criminalisation of a wide range of private sexual behaviours that do not infringe on the rights of other persons and that are the best representation of human heterogeneity and "normality" in all cultures.12–15 This denotes that current representations of sexuality are the outcome of a complex, dynamic process of changes in the social, political and historical context that privilege sexual responsibility and well-being.12,16,17 Downing18 argues that the pathologisation of paraphilia entails ideological rather than medical questions in favour of heteronormativity and reproduction as the core objective of sexuality. For zoophilic behaviours, it is possible that there will be a push for criminalisation or pathologisation due to the growing defence of animal rights; some authors believe that any contact with an animal with sexual intentions, even where it does not cause any evident pain or damage, could be referred to as animal sexual abuse.19–21

In summary, from a traditional perspective, paraphilias are sexual choices beyond the bounds of "normal" sexuality. From a critical perspective, these behaviours reflect particular social visions of acceptable sexual behaviour. And from an interrogatory point of view, careful consideration is needed to determine whether such behaviours are simply part of the spectrum of normal behaviour, and whether there is any clinical value in medicalisation over criminalisation of people who partake in non-consensual sexual behavior.12–18,22,23 For the particular case of zoophilia, it would be impossible to make a diagnosis if the person does not feel any distress due to sexual behaviour with animals, if they consider it a valid option.12,15–18

Knowledge of the frequency of paraphilic behaviours in the general population is very scant, almost anecdotal, as studies to date have taken biased samples.24 These behaviours have predominantly been researched in sex offenders,25–27 as predictors of antisocial behaviours28,29 and in patients diagnosed with other mental disorders.30–33 Knowing the prevalence in the general population can undoubtedly shed light on the discussion regarding the nature of zoophilic behaviours, whether they should be considered part of the "normal" sexual spectrum or infractions of criminal laws and, consequently, crimes or formal mental disorders that merit formal psychiatric treatment.12–15,22,23

MethodsA review was conducted of MEDLINE databases through PubMed, Scopus and the Virtual Health Library (VHL). The VHL is a digital resource that brings together biomedical information in Spanish and Portuguese that often cannot be found on MEDLINE and Scopus.

A wide search was performed, considering the large quantity of articles, such as case reports and other studies, that often report events in the general population. The search was limited to 21st century publications, from January 2000 to December 2017.

The group of key words included “paraphilia”, “zoophilia”, “cases” and “prevalence” in different combinations. These words were used in English, as well as in Spanish and Portuguese for the VHL. Narrative and systematic reviews were not considered. To reduce omissions of articles of interest, a manual review of the references of the articles identified in the initial searches was performed. A descriptive analysis was carried out, specifying the sociodemographic characteristics of the population, the evaluation method, the criteria used and the prevalence of zoophilic behaviours.

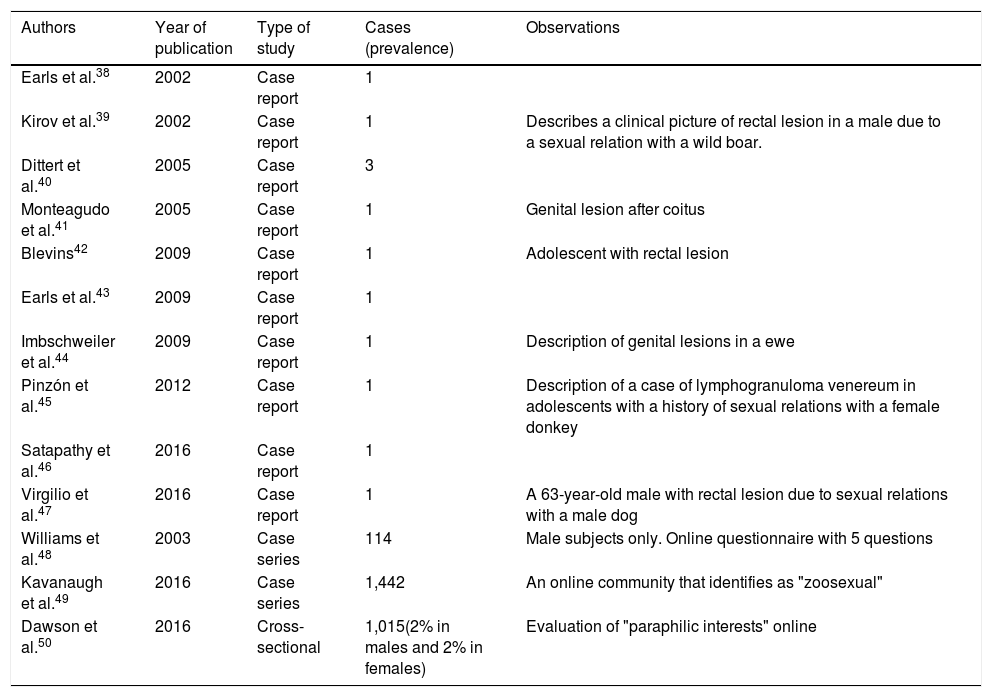

ResultsInitially, 17 articles were reviewed. Four works were excluded because the participants were not from the general population but from other contexts such as forensics, or because zoophilic-type paraphilic behaviours were not investigated.34–37 Ten case reports,38–47 two case series48,49 and one cross-sectional study50 were reviewed.

In summary, the case reports describe 12 participants, the case series total 1,556 people and the cross-sectional study included 305 male and 710 female subjects. Details of the works included can be seen in Table 1.

Overview of included publications.

| Authors | Year of publication | Type of study | Cases (prevalence) | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earls et al.38 | 2002 | Case report | 1 | |

| Kirov et al.39 | 2002 | Case report | 1 | Describes a clinical picture of rectal lesion in a male due to a sexual relation with a wild boar. |

| Dittert et al.40 | 2005 | Case report | 3 | |

| Monteagudo et al.41 | 2005 | Case report | 1 | Genital lesion after coitus |

| Blevins42 | 2009 | Case report | 1 | Adolescent with rectal lesion |

| Earls et al.43 | 2009 | Case report | 1 | |

| Imbschweiler et al.44 | 2009 | Case report | 1 | Description of genital lesions in a ewe |

| Pinzón et al.45 | 2012 | Case report | 1 | Description of a case of lymphogranuloma venereum in adolescents with a history of sexual relations with a female donkey |

| Satapathy et al.46 | 2016 | Case report | 1 | |

| Virgilio et al.47 | 2016 | Case report | 1 | A 63-year-old male with rectal lesion due to sexual relations with a male dog |

| Williams et al.48 | 2003 | Case series | 114 | Male subjects only. Online questionnaire with 5 questions |

| Kavanaugh et al.49 | 2016 | Case series | 1,442 | An online community that identifies as "zoosexual" |

| Dawson et al.50 | 2016 | Cross-sectional | 1,015(2% in males and 2% in females) | Evaluation of "paraphilic interests" online |

This review brings together case reports, case series and one prevalence study of zoophilia in the general population. Information is truly scant on this subject and it is difficult to accurately state the prevalence of zoophilic behaviours in the general population. The only cross-sectional study reports a prevalence of 2% in both men and women.50

It is extremely likely that the scarcity of valid and reliable data in this area is related to the negative connotations these behaviours have always had, from religious connotations such as sin, in the legal system as criminal, and to date as a mental disorder from the psychiatric medicine perspective.1,2,4–7

However, the growth of online communities and social networks has revealed that sexual behaviours included in the paraphilia category, including so-called zoophilic behaviours, are more common than was thought in the general population without dysfunction in the areas usually assessed when defining a mental disorder.51,52 This is understandable, since the internet allows people to remain anonymous, avoid the stigma-discrimination complex associated with heterodox sexual behaviours and find others with similar behaviours.53,54

The above suggests that it is becoming more difficult to uphold the validity of the diagnosis of paraphilic disorders.4,5,7 Even more so, if we accept that these sexual behaviours are often lasting, like personality characteristics,4,6,7 because of which they don't have a proven response to the treatments currently available.55

This research updates our knowledge about the prevalence of paraphilic behaviours in this general population, although, given the heterogeneity of the publications, it still cannot be precisely established.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, there is little information about the prevalence of zoophilic behaviours in the general population; the best available information indicates a prevalence of 2%. It is likely that the internet will enable these behaviours to be investigated in large samples in the coming years.

FundingThe Universidad del Magdalena [University of Magdalena], Santa Marta, funded the participation of Adalberto Campo-Arias and Guillermo A. Ceballos-Ospino and the Instituto de Investigación del Comportamiento Humano [Institute for Research in Human Behaviour], Bogotá, Colombia, backed Edwin Herazo as an author.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Campo-Arias A, Herazo E, Ceballos-Ospino GA. Revisión de casos, series de casos y estudios de prevalencia de zoofilia en la población general. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:34–38.