The offspring of bipolar parents (BO) is a high-risk population for inheriting the bipolar disorder (BD) and other early clinical manifestations, such as sleep disturbances.

ObjectiveTo compare the presence of psychiatric disorders and sleep disturbances of BO versus offspring of control parents (OCP).

MethodsA cross-sectional analytical study was conducted that compared BO versus OCP. The participants were assessed using valid tools to determine the presence of psychiatric symptoms or disorders. The “Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire” and “School Sleep Habits Survey” were used to determine sleep characteristics and associated factors. Sleep records (7-21 days) were also obtained by using an actigraphy watch.

ResultsA sample of 42 participants (18 BO and 24 OCP) was recruited. Differences were found in the presentation of the psychiatric disorder. The BO group showed a higher frequency of major depression disorder (MDD; P = .04) and Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD; P = .04). The OCP group showed a higher frequency of Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; P = .65), and Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD; P = .46). Differences were also found in sleep by using subjective measurements. Compared to the OCP group, BO had a worse perception of quality of sleep (P = .02), a higher frequency of nightmares (P = .01), a shorter total sleep time, and a higher sleep latency. Nevertheless, no differences were found between groups in the actigraphy measurements.

ConclusionsThe BO group had a higher frequency of Mood Disorders, and at the same time a higher number of sleep disturbances in the subjective measurements. It is possible that there is an association between mood symptoms, sleep disturbances, and coffee intake. No differences were found in the sleep profile by using actigraphy.

los Hijos de Padres con Trastorno Bipolar (HPTB) constituyen una población de riesgo ya que pueden heredar el Trastorno Bipolar (TB) como también manifestaciones clínicas tempranas como seria la alteraciones en el sueño.

Objetivocomparar la presencia de trastornos psiquiátricos y las alteraciones en el sueño de los HPTB con los Hijos de Padres Control (HPC).

MétodosSe realizó un estudio analítico de corte transversal, que comparó HPTB versus HPC. Se entrevistaron con instrumentos validados para determinar la existencia de síntomas y trastornos psiquiátricos. Utilizamos las escalas: “Cuestionario de evaluación de sueño” y “Encuesta sobre hábitos de sueño en escolares” para determinar las características del sueño y factores asociados con el mismo. Adicionalmente se obtuvo el registro de sueño (7-21 días) por medio de un reloj de actígrafia.

ResultadosSe reunió una muestra con 42 sujetos (18 HPTB y 24 HPC). Se encontraron diferencias en la presentación de los trastornos psiquiátricos. El grupo de HPTB presento mayor frecuencia del trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM; p = 0,04) y el trastorno disruptivo de la regulación emocional (TDRE, p = 0,04). En el grupo de HPC por su parte se presentó una mayor frecuencia de Trastorno por Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad (TDAH; p = 0,65) y de Trastorno de Ansiedad por Separación (TAS; p = 0,46). También se encontraron diferencias a nivel del sueño en las medidas subjetivas. En comparación con el HPC, el grupo de HPTB presento una peor percepción de la calidad de sueño (p = 0,02), una mayor presencia de pesadillas (p = 0,01), un menor tiempo total de sueño y una mayor latencia de sueño. Sin embargo, no se encontraron diferencias entre los dos grupos en las mediciones de actigrafías.

Conclusionesel grupo de HPTB presenta mayor frecuencia de trastornos del estado de ánimo, y a su vez una mayor presencia de alteraciones del sueño en las medidas subjetivas. Es posible que exista una asociación entre los síntomas afectivos, las alteraciones en el sueño y el consumo de café. No se encontraron diferencias en el perfil de sueño por actígrafía.

Bipolar disorder (BD) has an estimated global prevalence of 1%-2%; in Colombia, according to the 2003 Colombian National Study of Mental Health, its prevalence is estimated at 1.8%.1,2 A prevalence of 1.4% was found in Medellín in 2009.2 BD is considered to be among the leading causes of disability, with high social and family costs.3 According to various studies, 20%-40% of affected adults report that their BD started in childhood or adolescence.4

Children of parents with BD (COPBD) are a population at high risk of mental disorders. Studying this population may offer insight into prodromes and psychiatric disease in BD. A meta-analysis found that the risk of having a psychiatric disorder is 2.7 times higher for COPBD, and that the risk of having an affective disorder is 4 times higher than for children of control parents (COCP).5 Recent studies have indicated that relatives of patients with BD not only inherit the signs that make up the disorder per se, but also may present other abnormalities without clinical expression of BD.6 For example, the sleep–wake cycle has been identified as a possible endophenotype, since COPBD and the high-risk population show detectable abnormalities without having been diagnosed with BD.7 Sleep evaluation may be complex in children, as children have normal variations related to physical and brain development. Research has shown that up to 25% of healthy children may report sleep difficulties ranging from mild to serious, and furthermore may have sleep abnormalities due to various disorders predominantly occurring in childhood, such as anxiety disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, behavioural disorders and impulse-control disorders.8

Actigraphy has been used to evaluate the sleep–wake cycle, as it measures variability in body movements and therefore is useful in the diagnosis and follow-up of circadian rhythm disorders.9 It can also be used in the subject's natural environment, which may represent an advantage in the juvenile population.10 In addition, sleep scales and diaries completed by parents can be leveraged to compare and correct information obtained from actigraphy. These scales also collect other variables, such as daytime sleepiness; waking up during the night; perceived sleep quality; nightmares; bedwetting; need for company during the night; use of screens before going to bed; and use of caffeinated, energy and alcoholic drinks.11,12

Actigraphy has revealed that, compared to healthy controls, adults with BD still in remission may have longer sleep latency, longer sleep duration, lower sleep efficiency, changes in circadian rhythm amplitude and periods, and lower physical activity.9,13 Jones et al.,14 in a comparison of 25 COPBD 13-19 years of age to 22 COCP, found that the COPBD had shorter sleep latency, greater sleep fragmentation and a longer duration of waking on actigraphy, as well as higher perceived levels of non-reparative sleep and tiredness. Sebela et al.,158 for their part, compared 42 COPBD and 42 COCP paired by age and sex, finding that the former group had symptoms of sleep abnormalities associated with psychiatric symptoms and longer sleep latency.

These findings should be reproduced to clearly identify the most common and distinguishing patterns of activity in COPBD and to determine whether they are related to signs of psychiatric disease, with a view to proposing possible endophenotypes in BD. Hence, this study was conducted to compare psychiatric disease, sleep and activity measured by actigraphy as well as sleep scales and diaries in COPBD and COCP, and to determine whether any differences between these two groups might enable early identification of subjects likely to suffer from BD.

Material and methodsThis was a cross-sectional analytical study. It was conducted as part of the project "Cambios tempranos en población de alto riesgo para bipolar I disorder. Comparación de trastornos psiquiátricos, alteraciones de sueño y neuroimágenes entre hijos de pacientes con trastorno bipolar versus controles" [Early Changes in a Population at High Risk of Bipolar I Disorder: Comparison of Psychiatric Disorders, Sleep Abnormalities and Neuroimaging Among Children of Patients with Bipolar Disorder Versus Controls], conducted by the Universidad de Antioquia [University of Antioquia] Psychiatry Research Group (GIPSI).

ParticipantsThe participants were evaluated between October 2016 and November 2017. The following inclusion criteria were used: being 6 to 21 years of age and being in a condition to participate in a diagnostic interview and understand instructions for proper use of an actigraph unit (wristwatch). COPBD had to have a biological parent with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder according to the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR),16 previously made by the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS),17 and belonging to the Antioquian ("paisa") genetic isolate.18 COCP had to have both biological parents undiagnosed with BD according to the DIGS. The following possible subjects were excluded: those with a diagnosis of a mental disorder or autism spectrum disorder; those with a history of hydrocephalus, central nervous system surgery or traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness; those with structural or degenerative neurological lesions, epilepsy, or physical abnormalities interfering with their participation in a clinical interview; and those with rubber allergy as a specific contraindication for the use of the actigraph unit. Patients with sleep disorders were not excluded.

Instruments- •

The DIGS, developed by the United States National Institutes of Health,19 is used for genetic studies of schizophrenia and mood disorders. It allows for a reliable differential diagnosis and a detailed evaluation of psychosis, mood disorders and substance use disorders. It was translated and validated for Colombia and showed comprehensibility, appearance and content validity, and high test–retest and inter-rater reliability.17

- •

The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL), version 5, is a diagnostic interview that includes data on psychiatric disorders both in the present and over the course of one's life. It enables coding the number and duration of previous episodes, evaluating functional abnormalities related to specific diagnoses and assessing the interviewee's overall functioning through the Children's Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS). It also provides information on the subject's developmental history as well as family and medical history. Furthermore, it can determine the presence of subthreshold symptoms, considered a set of symptoms that create discomfort and disability but do not meet all the criteria that they must meet to be labelled with a diagnosis.20 The version in Spanish has good inter-rater reliability, as its validation yielded kappa coefficients >0.7 for more than half of disorders.21,22

- •

The C-GAS is a numerical scale used to classify the general functioning of subjects under 18 years of age. It is scored from 1 to 100 points: the higher the score, the better the functioning. Scores <30 are interpreted as an inability to function in most areas.23 The translation into Spanish showed acceptable reliability, with an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.61-0.91 for test–retest and inter-rater reliability, as well as suitable construct validity.24,25

- •

Sleep diaries are designed to collect information on daily sleep patterns in individuals in order to subjectively detect sleep abnormalities. Ideally, diary entries are prepared within one hour of waking up. The following items are recorded in the diary: bedtime, time of sleep onset, sleep latency time, number of episodes of waking up during the night and how long these episodes last (not counting getting out of bed), wake-up time and time of getting out of bed, rating of sleep quality and any additional comments that the subject deems pertinent.26

- •

The sleep evaluation questionnaire is a screening instrument filled in by parents, proposed by Owens et al.12,27 The items reflect a number of key sleep domains that translate to clinical sleep complaints. Its internal consistency, measured by Cronbach's alpha coefficient for each subscale, is 0.36 to 0.70 in a population sample of children 4 to 10 years of age. An abbreviated version of this scale expressly designed for research studies consists of 22 items with a response scale from 1 (always) to 5 (never).

- •

The survey on sleep habits in schoolchildren is an interview designed to evaluate sleep habits and behaviours in schoolchildren in the two weeks prior to the interview. Major variables include total sleep time, bedtime and time of getting out of bed on school days/nights and non-school days/nights. It also covers school performance and scales of daytime sleepiness, problems with sleep–wake behaviour and presence of symptoms of depression, with suitable internal consistency.28

The research protocol was approved by the Independent Ethics Committees of the Universidad de Antioquia Faculty of Medicine and the Hospital Universitario de San Vicente Fundación [San Vicente Fundación University Hospital] (HUSVF). Before data collection began, parents and their children had to sign the informed consent form and the informed assent form, respectively. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki in relation to ethical principles for medical research in human beings.29

The participants were contacted by telephone by a social worker from the research group. Once the inclusion criteria were met, clinical interviews were conducted and scales completed in a HUSVF office. The interview was prepared by a psychiatry resident, child psychiatry resident or psychiatrist. The evaluators were unaware of the presence or absence of a family history of BD. After the interview was held, two expert psychiatrists completed a "best estimate" diagnosis procedure in order to corroborate the psychiatric diagnosis. In case of discrepancy, the opinion of a third psychiatrist was sought.

The DIGS was applied to each parent to verify the presence of BD and other psychiatric disorders. Their children under 18 years of age were assessed using the K-SADS-PL, the sleep evaluation questionnaire and the survey of sleep habits in schoolchildren, which required the presence of one of the parents to aid in the application of the scales and the interview process.

After parents and children received an explanation of and training in how to complete the sleep diaries, the actigraph unit was placed on the non-dominant hand to be used for 14 days according to international standards;30,31 in addition, the parent in charge of supervision was sent an instructional video on actigraph unit use and sleep diary recording. Sleep was monitored by means of an actigraph unit in subjects who were willing to use the device on a continuous basis and whose parents agreed to its placement.

Philips Actiwatch Spectrum PRO (Philips) actigraph wristwatches were used;32,33 actigraph data were processed using the Actiware software program, provided by the actigraph manufacturer.

Statistical analysisThe SPSS 22.0 and STATA 14 statistics software programs were used for analyses. To describe the subjects, measure of central tendency and dispersion were used for quantitative variables, and frequencies and percentages were used for qualitative variables. Differences between COCP and COPBD were determined using Pearson's χ2 test for qualitative variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables.

A mixed-effects model was used in which the average of the variables was estimated, taking into account the random effect of the participant and the fixed effect of being COPBD or not. The model adjusted for the age variable was evaluated; however, given that no variations were found, the unadjusted model was preferred. For all tests, a threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05.

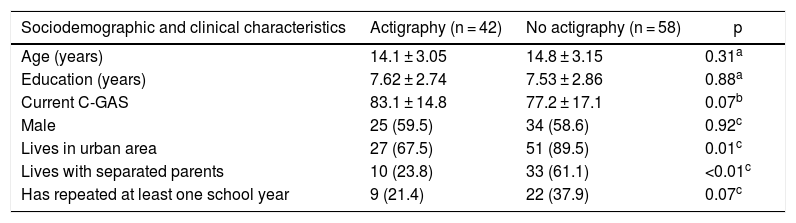

ResultsClinical and demographic variablesOne hundred participants were included and evaluated for psychiatric disease using the DIGS or K-SADS-PL and assessed using the sleep scales. Of them, 42 underwent sleep monitoring using an actigraph unit. The actigraphy subgroup was similar to the non-actigraphy subgroup in relation to age, sex, education and C-GAS functioning scale. The groups only showed differences with regard to origin and having separated parents. In addition, a larger number of subjects who had repeated more than one year of school was found in the group of children without actigraphy (Table 1).

Characteristics of the children who underwent actigraphy compared to those who did not.

| Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics | Actigraphy (n = 42) | No actigraphy (n = 58) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14.1 ± 3.05 | 14.8 ± 3.15 | 0.31a |

| Education (years) | 7.62 ± 2.74 | 7.53 ± 2.86 | 0.88a |

| Current C-GAS | 83.1 ± 14.8 | 77.2 ± 17.1 | 0.07b |

| Male | 25 (59.5) | 34 (58.6) | 0.92c |

| Lives in urban area | 27 (67.5) | 51 (89.5) | 0.01c |

| Lives with separated parents | 10 (23.8) | 33 (61.1) | <0.01c |

| Has repeated at least one school year | 9 (21.4) | 22 (37.9) | 0.07c |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

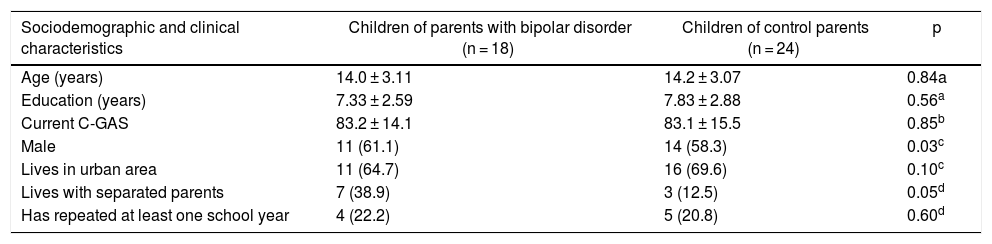

Comparison of the groups revealed that a higher proportion of COPBD lived with separated parents and that 13 subjects (72.2%) from that same group lived in the same house as the parent with BD. No differences were found with regard to age, education, C-GAS, urban or rural residence, or repeated years of school (Table 2).

Characteristics of the children of parents with bipolar disorder and the children of control parents.

| Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics | Children of parents with bipolar disorder (n = 18) | Children of control parents (n = 24) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14.0 ± 3.11 | 14.2 ± 3.07 | 0.84a |

| Education (years) | 7.33 ± 2.59 | 7.83 ± 2.88 | 0.56a |

| Current C-GAS | 83.2 ± 14.1 | 83.1 ± 15.5 | 0.85b |

| Male | 11 (61.1) | 14 (58.3) | 0.03c |

| Lives in urban area | 11 (64.7) | 16 (69.6) | 0.10c |

| Lives with separated parents | 7 (38.9) | 3 (12.5) | 0.05d |

| Has repeated at least one school year | 4 (22.2) | 5 (20.8) | 0.60d |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

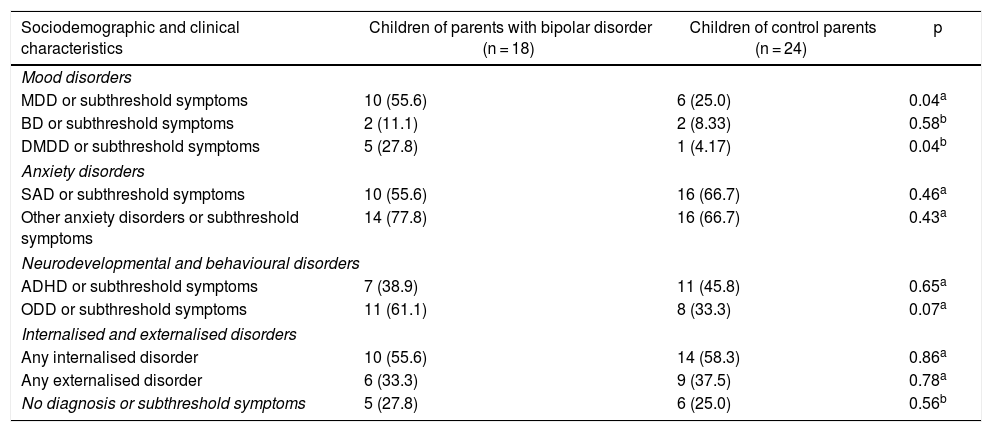

Compared to the COCP group, the COPBD group was found to have higher rates of mood disorders and subthreshold symptoms, specifically major depressive disorder (MDD) (p = 0.04) and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) (p = 0.04). No differences were seen between the groups in anxiety disorders, neurodevelopmental or behavioural disorders, or in internalised or externalised disorders. Some differences in the prevalence of some psychiatric disorders should be noted as they were of clinical, although not statistical, significance: in the COPBD group, there was a higher rate of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or subthreshold symptoms thereof (61.1%), and in the COCP group, there were higher rates of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (45.8%) and separation anxiety disorder (SAD) (66.7%) as well as subthreshold symptoms of those disorders (Table 3).

Psychiatric disease characteristics of the children of parents with bipolar disorder and the children of control parents.

| Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics | Children of parents with bipolar disorder (n = 18) | Children of control parents (n = 24) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mood disorders | |||

| MDD or subthreshold symptoms | 10 (55.6) | 6 (25.0) | 0.04a |

| BD or subthreshold symptoms | 2 (11.1) | 2 (8.33) | 0.58b |

| DMDD or subthreshold symptoms | 5 (27.8) | 1 (4.17) | 0.04b |

| Anxiety disorders | |||

| SAD or subthreshold symptoms | 10 (55.6) | 16 (66.7) | 0.46a |

| Other anxiety disorders or subthreshold symptoms | 14 (77.8) | 16 (66.7) | 0.43a |

| Neurodevelopmental and behavioural disorders | |||

| ADHD or subthreshold symptoms | 7 (38.9) | 11 (45.8) | 0.65a |

| ODD or subthreshold symptoms | 11 (61.1) | 8 (33.3) | 0.07a |

| Internalised and externalised disorders | |||

| Any internalised disorder | 10 (55.6) | 14 (58.3) | 0.86a |

| Any externalised disorder | 6 (33.3) | 9 (37.5) | 0.78a |

| No diagnosis or subthreshold symptoms | 5 (27.8) | 6 (25.0) | 0.56b |

ADHD: attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder; DMDD: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder; MDD: major depressive disorder; ODD: oppositional defiant disorder; SAD: separation anxiety disorder.

Values are expressed in terms of n (%).

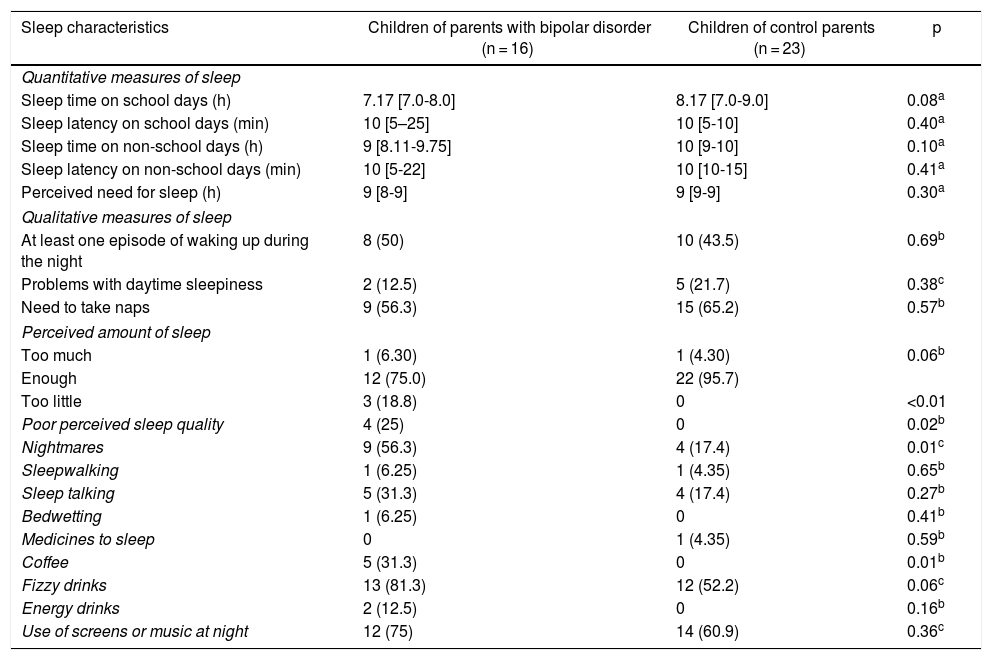

COPBD were found to have higher rates of poor perceived sleep quality, nightmares and coffee consumption. Regarding quantitative measures of sleep reported on scales, it was found that COPBD tended to report shorter overall sleep times on school days and non-school days, although the difference was not statistically significant. It was also found that the COPBD group had longer sleep latency on school days and non-school days, as indicated by the wider corresponding interquartile range; however, when medians were compared, no statistically significant differences were seen (Table 4).

Sleep characteristics according to the sleep evaluation questionnaire and the survey on sleep habits in schoolchildren.

| Sleep characteristics | Children of parents with bipolar disorder (n = 16) | Children of control parents (n = 23) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative measures of sleep | |||

| Sleep time on school days (h) | 7.17 [7.0-8.0] | 8.17 [7.0-9.0] | 0.08a |

| Sleep latency on school days (min) | 10 [5–25] | 10 [5-10] | 0.40a |

| Sleep time on non-school days (h) | 9 [8.11-9.75] | 10 [9-10] | 0.10a |

| Sleep latency on non-school days (min) | 10 [5-22] | 10 [10-15] | 0.41a |

| Perceived need for sleep (h) | 9 [8-9] | 9 [9-9] | 0.30a |

| Qualitative measures of sleep | |||

| At least one episode of waking up during the night | 8 (50) | 10 (43.5) | 0.69b |

| Problems with daytime sleepiness | 2 (12.5) | 5 (21.7) | 0.38c |

| Need to take naps | 9 (56.3) | 15 (65.2) | 0.57b |

| Perceived amount of sleep | |||

| Too much | 1 (6.30) | 1 (4.30) | 0.06b |

| Enough | 12 (75.0) | 22 (95.7) | |

| Too little | 3 (18.8) | 0 | <0.01 |

| Poor perceived sleep quality | 4 (25) | 0 | 0.02b |

| Nightmares | 9 (56.3) | 4 (17.4) | 0.01c |

| Sleepwalking | 1 (6.25) | 1 (4.35) | 0.65b |

| Sleep talking | 5 (31.3) | 4 (17.4) | 0.27b |

| Bedwetting | 1 (6.25) | 0 | 0.41b |

| Medicines to sleep | 0 | 1 (4.35) | 0.59b |

| Coffee | 5 (31.3) | 0 | 0.01b |

| Fizzy drinks | 13 (81.3) | 12 (52.2) | 0.06c |

| Energy drinks | 2 (12.5) | 0 | 0.16b |

| Use of screens or music at night | 12 (75) | 14 (60.9) | 0.36c |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%) or median [interquartile range].

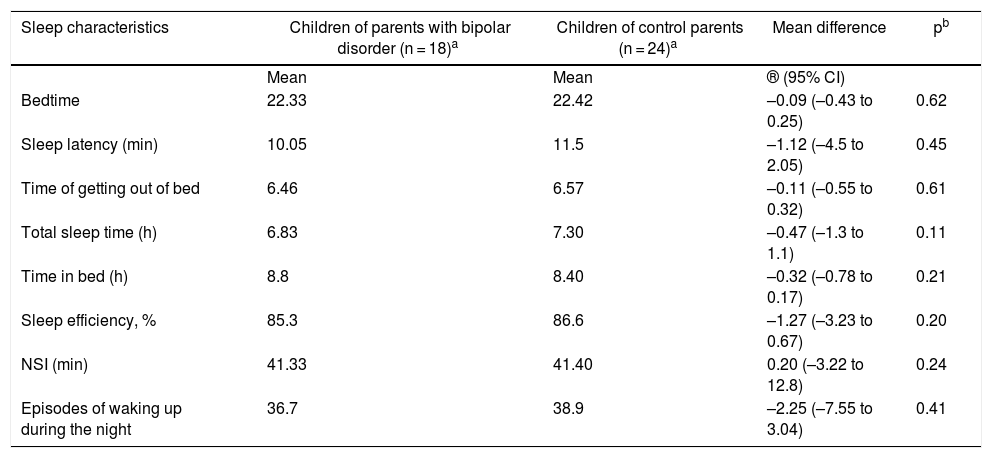

No significant differences were found in the actigraphy measurements between the COCP and COPBD groups. However, total sleep time was seen to be lower in the COPBD group than in the COCP group (Table 5).

Sleep characteristics according to the actigraph unit.

| Sleep characteristics | Children of parents with bipolar disorder (n = 18)a | Children of control parents (n = 24)a | Mean difference | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ® (95% CI) | ||

| Bedtime | 22.33 | 22.42 | –0.09 (–0.43 to 0.25) | 0.62 |

| Sleep latency (min) | 10.05 | 11.5 | –1.12 (–4.5 to 2.05) | 0.45 |

| Time of getting out of bed | 6.46 | 6.57 | –0.11 (–0.55 to 0.32) | 0.61 |

| Total sleep time (h) | 6.83 | 7.30 | –0.47 (–1.3 to 1.1) | 0.11 |

| Time in bed (h) | 8.8 | 8.40 | –0.32 (–0.78 to 0.17) | 0.21 |

| Sleep efficiency, % | 85.3 | 86.6 | –1.27 (–3.23 to 0.67) | 0.20 |

| NSI (min) | 41.33 | 41.40 | 0.20 (–3.22 to 12.8) | 0.24 |

| Episodes of waking up during the night | 36.7 | 38.9 | –2.25 (–7.55 to 3.04) | 0.41 |

NSI: night sleep interval (period of time from falling asleep to first waking up).

This study was conducted with the objective of comparing an evaluation of psychiatric disease and sleep characteristics in an at-risk population furthermore belonging to a genetic isolate in which certain distinctive characteristics have been identified in previous studies.18,34,35

Changes in sleep by subjective measuresDifferences were found between the groups in sleep characteristics, especially on subjective measures such as scales. COPBD were seen to have worse sleep quality than COCP, higher numbers of nightmares and higher rates of coffee consumption. Sleep abnormalities have been studied as precursors to mood disorders. In this regard, Fredriksen et al.36 observed a relationship between sleep abnormalities, symptoms of depression and a decrease in self-esteem in a group of middle school-aged children. Another study demonstrated the relationship between nightmares and a higher rate of behavioural difficulties, which, when chronic, led to increased stressors.36,37 These studies back the explanation that this COPBD group may have sleep abnormalities corresponding to symptoms of a depressive condition or precursors to other psychiatric disorders. They would also support the notion that this at-risk group is showing a BD endophenotype.

Subjective abnormalities in sleep quality have also been reported in other studies in at-risk populations. Sebela et al.15 evaluated 42 COCP without psychiatric disease and 42 COPBD using self-administered scales filled in by parents, finding higher rates of nightmares and daytime sleepiness in the COPBD group. Scott et al.,38 for their part, compared 12 COPBD and 48 COCP and found no significant differences with respect to reported sleep quality, though the subjects were experiencing an episode of major depression at the time of the study. Perceived sleep quality appears to be related to cultural factors and sleep hygiene. Some studies have indicated a correlation between sleep hygiene practices and perceived sleep quality in healthy adolescents, with differences between cultures.39 This would point to a need to evaluate sleep practices in COPBD as well as in their homes.

In this, a higher rate of coffee consumption was reported in the COPBD group. This consumption may stem from sleep abnormalities, creating a vicious cycle in which poor sleep quality leads to coffee consumption and abstaining from coffee leads to a feeling of fatigue and low mood. In this regard, Whalen et al.40 reported a relationship between symptoms of depression, sleep abnormalities and coffee consumption as self-medication for fatigue and sleepiness. They also reported that abstaining from coffee caused these symptoms to recur, leading subjects to resume coffee consumption. This could account for the association between coffee consumption, symptoms of depression and poor sleep quality in our COPBD population. One repercussion of substantial coffee consumption is poorer performance in school. One study in this vein demonstrated the role of environmental factors in sleep patterns, finding a shorter overall sleep time to be associated with worse academic performance.41

Coffee and other caffeinated beverages, such as fizzy drinks and energy drinks, have become more widely distributed and available to a young population. Various studies have focused on the existing relationship between caffeine consumption in children and adolescents and its association with academic performance.42 On the one hand, Tennant et al.43 conducted a study with 1,354 subjects in the United States army, reporting that those who used illicit drugs and alcohol had started to use alcohol, cigarettes and caffeine before they turned 12. On the other hand, Jin et al.44 studied 308 adolescents 15-17 years of age, and found higher caffeine consumption and higher alcohol consumption to be associated with worse academic performance and higher scores for depression, anxiety, insomnia and stress. These two studies emphasised that the younger one's age, the higher their risk of addiction; they also stressed the relationship between caffeine and alcohol use and future mood and anxiety disorders.

Changes in sleep by objective measuresAnalysis of actigraphy data did not reveal differences between the two groups. One possible explanation is the limited power of this study given its small sample size, pointing to a possible type II error. However, in the field of actigraphy, the differences between the COPBD and COCP groups reported by other authors were not consistent. Regarding sleep latency, Jones et al.14 found it to be longer in COCP (mean: 28.31 min), whereas according to Sebela et al.,15 sleep latency was longer in COPBD (mean: 17 min). Studies in adults with BD have indeed demonstrated consistent findings, indicating longer sleep latency. There is also total sleep time; Jones et al.14 reported that it was longer in COPBD than in COCP (mean: 31.67 min), while Sebela et al.15 found a difference of just two minutes between the groups.

Psychiatric disordersThis study found higher rates of MDD and DMDD as well as higher rates of subthreshold symptoms of these disorders in the COPBD group. This was consistent with similar studies having found a predominance of affective disorders in COPBD compared to COCP. For example, in a systematic review of the literature conducted by Raouna et al.,45 COPBD were a group at high risk of affective and non-affective psychiatric disease in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Specifically, Birmaher et al.46 found a 13 times higher risk of mental disorders in COPBD versus COCP. The findings of this study pointed in the same direction as others indicating a higher risk of mood disorders in this population.15,47,48

In addition, a higher rate of ODD was found in the COPBD group. Aronen et al.49 compared sleep in 30 children with ODD and 30 children with psychiatric disease and confirmed that the patients in the former group had greater sleep problems, based on both reports and actigraphy measurements; specifically, they had shorter sleep times and lower sleep efficiency related to externalised symptoms reported by their parents. This might in some way explain the reports of poor sleep quality in the COPBD group.

High prevalences of SAD and ADHD were found in the COCP group, and although there was no difference between the groups, this must be treated in light of sleep abnormalities. Becker et al.,50 in a study in 181 subjects with ADHD, reported difficulties in several aspects of sleep, such as sleep anxiety, bedtime resistance and waking up during the night. These findings suggest that, in the current sample, various participants with ADHD in both groups could have sleep abnormalities, and for this reason no differences were seen in some subjective parameters and objective measures. It should be borne in mind that the comparator group was selected based on a control parent who did not have BD, but whose offspring might have had certain psychiatric disorders based on the K-SADS evaluation, except for intellectual disabilities or autism spectrum disorders. Other studies have already reported COCP to have anxiety disorders, ADHD and ODD, and some effects on their results for sleep variables have been found, though at lower rates than the COPBD group.51 In addition, anxiety disorders may be associated with sleep abnormalities. For example, Iwadare et al.52 reported abnormalities such as bedtime resistance, sleep anxiety, waking up during the night and abnormalities in total sleep in children with generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), SAD, social phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In addition, Alfano et al.53 evaluated sleep-related problems associated with GAD, SAD and social phobia, and found bedtime resistance, delayed sleep onset, daytime sleepiness and abnormalities in total sleep.52

In summary, in the population studied, COPBD were found to have higher rates of ODD and anxiety disorders in general, and COCP were found to have higher rates of SAD in particular, which could explain why the populations showed no differences in terms of presentation of sleep variables. These variables should be controlled in future studies.

Clinical implicationsBased on these findings, it can be affirmed that COPBD are a population at higher risk of experiencing affective symptoms and disorders than COCP. In addition to this, COPBD have worse perceived sleep quality and more nightmares. This may be tied to higher rates of coffee consumption in this group. Therefore, we wish to propose not only that active efforts be made to detect psychiatric disease in this age group, but also that sleep hygiene regimens be promoted among relatives of adult patients with BD, especially COPBD.

Sleep hygiene measures are, in reality, among the most important recommendations for children and adolescents in the treatment of sleep abnormalities, regardless of whether or not they are associated with psychiatric disease. A lack of such measures leads to sleep abnormalities, as already demonstrated by Mindell et al.54 in an analysis of reports from 1,473 parents on the sleep of their children (0 to 10 years of age). They reported that using screens in bed, consuming caffeine at night and getting out of bed before dawn were significantly associated with sleep abnormalities.

Limitations and future studiesThe limitations of this study included its sample size, which might have been too small to find the differences cited in prior studies, corresponding in that case to a type II error. In addition, the subjects selected may have struggled to use diaries and manage the actigraph unit given their youth, which might have led to measurement bias. Finally, although various control parents were invited, it is difficult to know whether those who agreed to take part did so in order to have their children evaluated or out of some particular interest such as detection of a psychiatric disorder. This might have been a source of bias.

To our knowledge, this was the first study on sleep conducted in Latin America in this at-risk population. It is essential to conduct further research in this area with larger sample sizes that would enable analysis of differences in actigraphy. In addition, measures of school performance that would identify the impact of sleep abnormalities on subjects' daily lives should be included. BD largely begins in adolescence, meaning it is essential to perform subgroup analyses to characterise this at-risk population and to evaluate differences due to expected normal changes and differences due to possible developing or established psychiatric disease.

ConclusionsThis study confirmed higher rates of affective disorders and symptoms in the COPBD group. It also identified some subjective measures that show sleep abnormalities, such as poor perceived sleep quality, more reported nightmares and higher rates of coffee consumption in this group. Affective symptoms may be associated with sleep abnormalities and coffee consumption, which should continue to be investigated as potential early markers of BD onset. No differences were found between the groups in actigraphy recording; however, the study's limited statistical power should be borne in mind. Studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm sleep abnormalities with objective measures such as actigraphy in the population at risk of BD.

FundingThis study was funded by COLCIENCIAS, Code No. 1115 7114 9700, and by the Colciencias PRISMA Project, Code No. 99059634, in collaboration with the Universidad de Antioquia Faculty of Medicine and the Universidad de Antioquia Research Development Committee (CODI).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the families who took part in this study; María Cecilia López, Patricia Montoya, Aurora Gallo and all the members of the GIPSI for their help and support in contacting the participating families; the Universidad de Antioquia CODI; and the Universidad de Antioquia Sustainability Strategy.

Please cite this article as: Estrada-Jaramillo S, Quintero-Cadavid CP, Andrade-Carrillo R, Gómez-Cano S, Erazo-Osorio JJ, Zapata-Ospina JP, et al. ¿Los hijos de pacientes con trastorno bipolar tienen una peor percepción de la calidad de sueño? Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:25–34.