Severe mental disorders can cause significant and lasting distress for patients and their families and generate high costs through the need for care and loss of productivity. This study tests DIALOG+, an app-based intervention to make routine patient-clinician meetings therapeutically effective. It combines a structured evaluation of patient satisfaction with a solution-focused approach.

MethodsWe conducted a qualitative study, based on a controlled clinical trial, in which 9 psychiatrists and 18 patients used DIALOG+ monthly over a six-month period. Semi-structured interviews were used to explore the experiences of participants and analysed in an inductive thematic analysis focusing on the feasibility and effects of the intervention in the Colombian context.

ResultsExperiences were grouped into five overall themes: a) impact of the intervention on the consultation and the doctor-patient relationship; b) impact on patients and in promoting change; c) use of the supporting app, and d) adaptability of the intervention to the Colombian healthcare system.

ConclusionsDIALOG+ was positively valued by most of the participants. Participants felt that it was beneficial to the routine consultation, improved communication and empowered patients to take a leading role in their care. More work is required to identify the patient groups that most benefit from DIALOG+, and to adjust it, particularly to fit brief consultation times, so that it can be rolled out successfully in the Colombian healthcare system.

Las enfermedades mentales graves producen un impacto significativo en términos de sufrimiento de los pacientes y sus familias, costos de atención y años de vida perdidos por discapacidad. Este estudio pone a prueba la herramienta DIALOG+, una intervención basada en una App que combina una evaluación estructurada referente a 11 dominios, con un abordaje centrado en soluciones.

MétodosEstudio cualitativo anidado en un ensayo clínico controlado en el que 9 psiquiatras y una muestra intencional de 18 pacientes que utilizaron la aplicación DIALOG+ en controles mensuales durante 6 meses realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas sobre su experiencia.

ResultadosEl análisis se enfocó en determinar la aceptabilidad, la viabilidad y la efectividad de la intervención en el contexto colombiano mediante el método de análisis temático inductivo propuesto por Braun y Clarke. Los resultados fueron: a) impactos en la consulta y la relación médico-paciente; b) impactos en los pacientes y promoción del cambio; c) uso de la aplicación, y d) adaptabilidad al sistema de salud.

ConclusionesEl instrumento DIALOG+ fue valorado positivamente por la mayoría de los participantes, dado que aporta al seguimiento de los pacientes con enfermedad mental grave porque incluye un componente psicoterapéutico en las consultas habituales y mejora la comunicación y el paciente se apropia de su proceso. Sin embargo, es pertinente delimitar la población que podría percibir los mayores beneficios y ajustar su esquema, sobre todo en relación con el tiempo de consulta, para que resulte exitosa su adaptación al sistema de salud colombiano.

In 2016, mental and addictive disorders accounted for 7% of all global burden of disease, as measured in disability-adjusted life years, and 19% of all years lived with disability, and cause greater vulnerability, not only in health but also in terms of psychosocial aspects and human rights violations.1–3 Although this behaviour has become evident in general and is gaining importance as the burden caused by communicable diseases decreases, a gap exists when it comes to accessing evidence-based interventions for patients with mental illnesses compared to those who suffer from other types of conditions, which is more pronounced when comparing low- and middle-income countries with high-income countries.4–7 Given this scenario, it is necessary to strengthen the supply and coordination of efficient interventions in outpatient and hospital departments, and to improve the global research capacities.8,9

According to the 2015 National Mental Health Survey of Colombia, the lifetime prevalence of assessed mental illnesses (depression, dysthymia, affective disorders and anxiety disorders) among the general population was 9.1%. With regards to actions aimed at the comprehensive care of patients with mental disorders, one recommendation is to investigate new methodologies that may help improve patient care and access to psychotherapeutic interventions.10,11

The DIALOG+ tool is based on quality-of-life research, concepts of patient-centred communication, IT developments and components of solution-focused therapy. Its implementation is intended to ensure that meetings between the patient with mental illness and his or her clinician are effective during outpatient follow-up.12 Using an app, the patient is able to rate their satisfaction with eight life domains and three aspects relating to their treatment. The patient then chooses the domain(s) they want to discuss during the consultation following a four-step approach:

- 1

Understanding (if the score is not the lowest, what is working well within that domain?).

- 2

Looking forward (what is the best-case scenario?, and what is the smallest step forward that would make a difference?).

- 3

Exploring options (what can the patient, clinician and others do to make a difference?).

- 4

Agreeing on actions.

All this information is available for review and comparison.13,14

In cluster-randomised controlled trials conducted in other countries, DIALOG+ was associated with a better subjective quality of life, comparable to that achieved with cognitive-behavioural therapy, and also with fewer unmet needs, lower intensity of symptoms, better social conditions and lower treatment costs.15,16

Bearing in mind that evidence available from studies conducted in high-income countries cannot be extrapolated to middle- or low-income regions, local research is needed to explore the effectiveness of interventions like DIALOG+.13,17,18 The use of quantitative and qualitative methodologies to evaluate the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of the intervention may be complementary and may enrich the interpretation of results.18 Therefore, this study aims to qualitatively assess the acceptability of using the DIALOG+ tool at follow-ups of patients with severe mental illness. The results of the quantitative study are presented in a separate article.

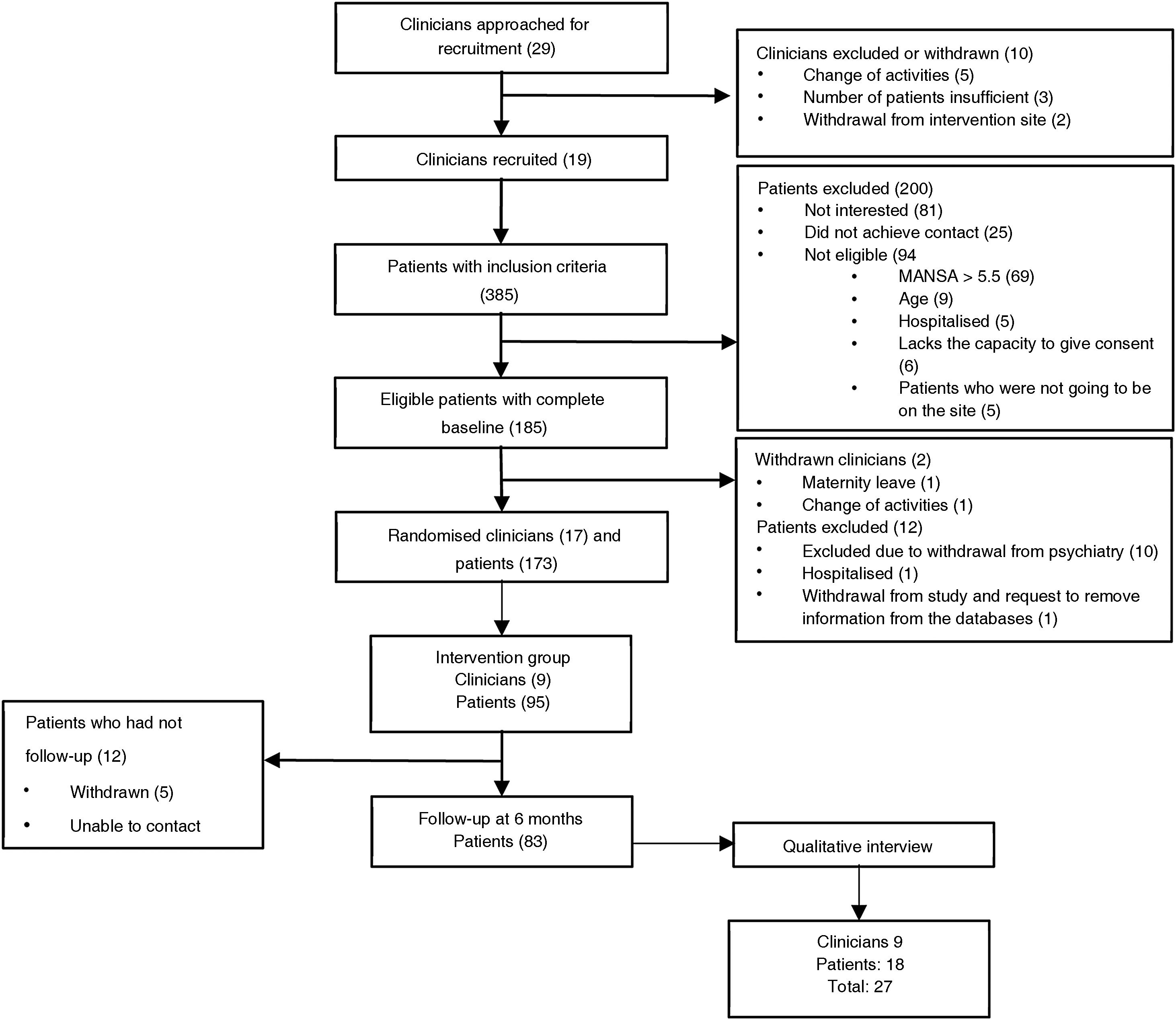

MethodsDesignQualitative study that assessed clinicians and an intentional sample of patients using a semi-structured interview to test the effectiveness of the DIALOG+ tool in the outpatient follow-up of patients with severe mental illness. This qualitative study is part of a cluster-randomised controlled clinical trial that assessed DIALOG+ using quantitative methods. All interviewees belong to the active group of the trial.

Participants and sitesThe groups were made up of 17 clinicians (psychiatrists or psychiatry residents with at least 3 months of experience at the healthcare site; in the final group there were 4 second-year residents and 13 psychiatrists) and their respective patients in the outpatient departments of four hospitals dedicated to caring for patients with mental illness, two public and two private: Clínica Fray Bartolomé, Clínica la Inmaculada, IPS Campo Abierto de Bogotá and Hospital Departamental Psiquiátrico Universitario del Valle de Cali. Clinicians were selected from all the doctors working at the recruited institutions. They were randomised using the STATA software tool so that both they and their patients were assigned to one of two groups: the group that used the DIALOG+ intervention (active group) or the group that continued with the usual treatment (control group). The choice of the cluster-randomised method sought to prevent contamination of the interventions. Spanish-speaking investigators translated DIALOG+ from its original English version. The investigators instructed clinicians of the active group on how to use the tool according to a standardised methodology with both a theory and role-play component.

A sample of 173 patients was calculated. The patient inclusion criteria were: aged 18 to 65 years, diagnosed with a serious mental disorder (ICD F20-29, F31, F32), and able to give informed consent and visit the clinic for at least 6 months. The exclusion criterion was to score >5.00 on the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA), given that, as this was the main endpoint to be assessed in the quantitative study, it was necessary to choose a cut-off point that would make it possible to observe variations in the score after the intervention. Spanish-speaking investigators translated the MANSA scale from English. This is not validated and was selected due to it being widely comparable with similar studies.

Fig. 1 summarises the consort for participants over the course of the study. A detailed description of the procedure is available in the protocol (ISRCTN83333181; 20-11-2018, prospective).

InterventionsIn the active group, monthly consultations were scheduled, in which the DIALOG+ tool was applied during the first 6 months, with a flexible period to use the app for an additional 6 months.

In the control group, monthly follow-ups were scheduled for 6 months, following the usual structure for Psychiatry care at the respective institution.

Interventions were performed for 1 year from April 2019.

Data collectionAt the 6-month follow-up, all clinicians in the active group (9 in total) and a convenient sample of two patients for each clinician from the same group (18 in total) conducted a semi-structured interview about their experience using DIALOG+, based on the following issues: a) participation in the study; b) experience with the intervention; c) impact and scope; d) evaluation and recommendations, and e) practical aspects. Patients were chosen and interviewed, nonblinded, by a researcher, seeking diversity in aspects such as sex, age group, diagnosis and compliance with appointments for interventions. The semi-structured interviews were piloted with the support of researchers from the team who were experienced in talking to patients with mental illness. These interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed using the inductive thematic analysis technique proposed by Braun et al.19 Three investigators familiarised themselves with the transcripts and created themes and codes reflecting the participants’ experiences, and these were discussed with the research team and modified through iterations. In order to obtain categories, inductive content analysis was applied, during which categories emerged from the collected data. Subsequently, two investigators coded the transcripts using NVivo® 12 qualitative analysis software.

In order to unify coding criteria among evaluators, a joint coding of 20% of the texts was initially performed, from which the Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated, and >80% agreement was found. This exercise allowed us to confirm the relevance and reliability of the themes and codes, after which some modifications were made that did not significantly affect the initial version, and a final version was created.

All methods and tools used were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Queen Mary University of London and the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Hospital San Ignacio, following the protocols established in the Good Clinical Practice Guidance according to Colombian legislation. The analysis plan was drafted and signed by the principal investigators before starting this process. None of the interviews were corrected or conducted a second time. Interviews were conducted between October 2019 and May 2020, with twenty conducted in person and nine conducted over the phone due to the national COVID-19 quarantine period.

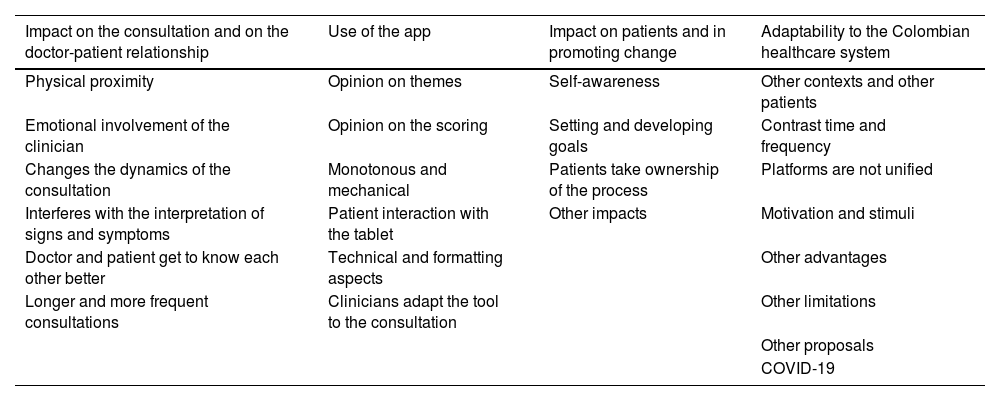

ResultsThe final themes and codes are presented in Table 1. Once all transcripts had been coded, a report was generated describing the contents of each code, which was the basis for the synthesis of results. A summary of each theme is presented below and illustrative quotes differentiated by the category of the participant, clinician or patient are shown in Tables 2–4.

Coding framework.

| Impact on the consultation and on the doctor-patient relationship | Use of the app | Impact on patients and in promoting change | Adaptability to the Colombian healthcare system |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical proximity | Opinion on themes | Self-awareness | Other contexts and other patients |

| Emotional involvement of the clinician | Opinion on the scoring | Setting and developing goals | Contrast time and frequency |

| Changes the dynamics of the consultation | Monotonous and mechanical | Patients take ownership of the process | Platforms are not unified |

| Interferes with the interpretation of signs and symptoms | Patient interaction with the tablet | Other impacts | Motivation and stimuli |

| Doctor and patient get to know each other better | Technical and formatting aspects | Other advantages | |

| Longer and more frequent consultations | Clinicians adapt the tool to the consultation | Other limitations | |

| Other proposals | |||

| COVID-19 |

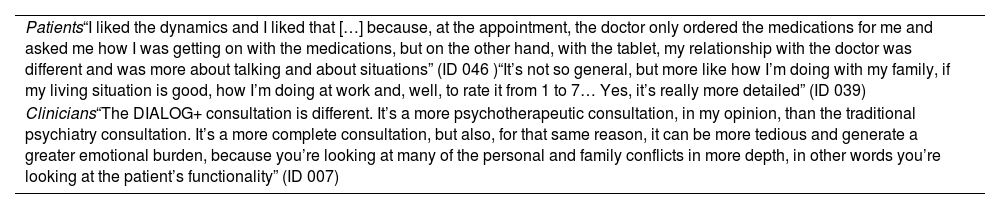

Impact on the consultation and the doctor-patient relationship.

| Patients“I liked the dynamics and I liked that […] because, at the appointment, the doctor only ordered the medications for me and asked me how I was getting on with the medications, but on the other hand, with the tablet, my relationship with the doctor was different and was more about talking and about situations” (ID 046 )“It’s not so general, but more like how I’m doing with my family, if my living situation is good, how I’m doing at work and, well, to rate it from 1 to 7… Yes, it’s really more detailed” (ID 039) |

| Clinicians“The DIALOG+ consultation is different. It’s a more psychotherapeutic consultation, in my opinion, than the traditional psychiatry consultation. It’s a more complete consultation, but also, for that same reason, it can be more tedious and generate a greater emotional burden, because you’re looking at many of the personal and family conflicts in more depth, in other words you’re looking at the patient’s functionality” (ID 007) |

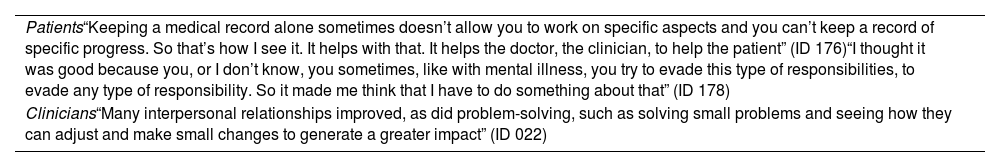

Impact on patients and in promoting change.

| Patients“Keeping a medical record alone sometimes doesn’t allow you to work on specific aspects and you can’t keep a record of specific progress. So that’s how I see it. It helps with that. It helps the doctor, the clinician, to help the patient” (ID 176)“I thought it was good because you, or I don’t know, you sometimes, like with mental illness, you try to evade this type of responsibilities, to evade any type of responsibility. So it made me think that I have to do something about that” (ID 178) |

| Clinicians“Many interpersonal relationships improved, as did problem-solving, such as solving small problems and seeing how they can adjust and make small changes to generate a greater impact” (ID 022) |

Use of the app.

| Patient“Everything was only handled by the psychiatrist, but I had access to look at the tablet, and that also seemed important to me” (ID 077) |

| Clinicians“Suddenly the domain that seemed most strange to me was the one to do with the healthcare system and the services made available to the patient by the healthcare system, perhaps because Colombia isn’t known for having a good service in that sense. So it seemed to me like a slightly strange domain” (ID 007)“Well, the scale seems good to me. 7 points seems like enough to me. However, I think it could be more specific in terms of intermediate scores: I don’t think there is any linguistic clarity between “very” and “quite” to distinguish between them clearly. Therefore, I think that both the patients and I were guided more by the number" (ID 007) |

Some clinicians stated that DIALOG+ helped them to include in patient follow-ups aspects of their lives that were neglected during their usual consultations. The structure proposed by the app allows psychotherapeutic interventions to be carried out during regular meetings. This fact, while making the consultation more complete, also generated tension when addressing themes that are generally avoided due to their length or complexity.

Clinicians positively appraised that the app helped them discuss different aspects of the examination of patient’s signs and symptoms, learn about other aspects of the patients’ lives, learn from them and feel that the relationship was not determined by a hierarchy. With respect to the identification of signs and symptoms, it became clear that the tool was of little use. One of the clinicians indicated that one patient with mania-like symptoms had favourably rated all the themes proposed by DIALOG+, which gave the impression that his condition had improved, when in fact he had gotten worse. Another clinician made a similar observation regarding overestimation of well-being in a specific area for a delirious patient. The impression was that the tool could cause confusion in such situations and the scores obtained in the different domains should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the patient could feel less motivated to thoughtfully answer the questions proposed by the app when they arrive at the consultation with the need to express themes related to their worsening symptoms.

Patients indicated that communication with the clinician changed when using DIALOG+. They had the perception that they could talk more, that more time was spent with them, their concerns were given more importance and that areas besides the prescription of antipsychotics were covered. DIALOG+ made it easier to start a conversation; the proposed themes made them focus and be more sincere, and thanks to the graphic tools, they felt that the aspects addressed were tangible. One of the patients indicated that this change was not associated with use of the app but rather with the receptive attitude of the professional who was in charge of follow-ups.

Following the proposed interview technique, clinicians and patients sat closer together and they could overcome the feeling of a barrier generated by the desk and computer on which the patient’s medical history was recorded. This influenced the emotional commitment, changed the perspective from which the patient was observed, but also turned out to be uncomfortable and generated fear when assessing patients with psychotic symptoms who were inclined to react due to the invasion of their personal space.

Impact on patients and in promoting changeSome clinicians highlighted the positive impact of the tool on patients who were given simple tasks that could be accomplished in a short period of time. Others mentioned that not all tasks were easy to accomplish or follow during the study, which generated frustration. Some sought to empower the patient to increase their autonomy and find solutions through their own resources, as well as to alert their family about the help they needed. Another clinician highlighted the fact that the tool makes it possible to involve the support network in the improvement plan so that the impact of the tasks is extended to this network.

Several patients highlighted that the incorporation of DIALOG+ into the psychiatry consultation allowed them to increase their self-awareness, identify themes in which they were “weak” and the type of help they needed in order to improve in the domains in which they scored low. They highlighted its practicality. Some emphasised that addressing these themes invited them to reflect outside of the consultation, in preparation for the latter, or in their daily lives. The score allowed them to keep track of their progress and setbacks, as well as recapitulate on themes discussed in previous consultations. Patients mentioned that the tool helped them assume a more active role.

Other impacts in addition to those mentioned above were: changes in family relationships, physical health, employment, social relationships and self-confidence. Some patients perceived a link between a reduction in their medication and the use of the app in the consultations. For one patient, it helped him to improve his medication adherence while reducing his dose.

Finally, it should be noted that some patients did not identify improvements or changes in their lives when using the app.

Use of the appIn general, interviewees agreed with the eleven domains that appear on the app as they consider them to be relevant and sufficient. Among the most relevant themes were “family”, “leisure and free time”, “work” and “mental health”. The majority of clinicians justified keeping all of the domains, although a few considered that “Practical help” should be deleted. However, some omitted or skimmed over themes that they did not consider relevant or that were somewhat problematic in each individual case. As a result, they proposed that, at initial consultations, it should be possible to discard themes that are of little interest to the patient or that cannot really be modified to their context and resources. With regards to the patients, although some had problems broaching and meeting goals related to employment and social relationships, they generally considered that all the items included were important and related to their lives.

According to the interviewees, the clinicians generally handled the tablet while sitting next to their patients and invited them to rate and choose the themes they wanted to discuss at the consultation. All the patients interviewed agreed or were indifferent to the clinician holding the tablet. They clarified that they were always allowed to see the tablet, which they rated as positive, and preferred this to using the computer, as in the latter scenario they could not read what was being written about them.

Overall, those interviewed found the scale and its scoring options to be appropriate. Some patients had difficulty understanding it, but this decreased as patients became more familiar with the app. One of the most common comments in this regard concerns linguistic confusion in relation to the intermediate options (very, quite a bit, little). Due to this, clinicians and patients tended to go by the numbers for scoring. They also claimed that the difficulty in understanding the scale was due to the way in which the questions were expressed, and therefore they propose amending the translation.

Adaptability to the healthcare systemOne of the limitations identified not only by the clinicians, but also by the patients, when using DIALOG+ regularly during psychiatry follow-ups, was that the 30 minutes assigned to the consultation with the specialist were insufficient and the availability of appointments in the institutions did not allow monthly follow-ups to be assigned outside of the study. The volume of patients assigned each day turned out to be a concern for the clinicians, who complained about prolonging the waiting time of other patients due to the longer consultation times using DIALOG+. The general perception was that tasks such as generating service orders, prescriptions, authorisations and medical records, in addition to performing the intervention guided by the app, caused the consultation to last for up to 40–50 minutes. The extra time and resulting adaptations were assumed by the clinicians, and this affected their preference to continue using the app within regular healthcare. They further noted that this difficulty would limit the use of DIALOG+ by general practitioners, despite the user-friendliness of the app, because their consultation time was shorter. One of the clinicians even proposed that an abbreviated version be created to overcome issues with time management. It was pointed out by one of the patients that the structuring of DIALOG+, instead of lengthening the consultation, could facilitate a more efficient use of the allotted 30 minutes.

One of the aspects that contributes to the feeling that the interventions are longer and more tedious has to do with using two platforms during the consultation: the app on the tablet and the institutional medical record format on the desktop computer.

They also pointed out some populations in which, in their opinion, the app would be difficult to use or of little use: patients with personality disorders or disorganised thoughts associated with an acute phase of their mental illness. One of the clinicians pointed out that DIALOG+ is easy to integrate and shows its greatest benefit in patients diagnosed with depression, bipolar affective disorder in remission and schizophrenics in the maintenance or stabilisation phase with no significant cognitive impairment.

One of the proposals that appeared to make it possible to implement DIALOG+ in the routine follow-up of patients was to organise an interdisciplinary care pathway, based on the content discussed whilst using the tool, in order to work as a team in the intervention areas.

Participants generally considered that the tool was easy to use and they quickly got used to it. However, patients with cognitive impairment and those who are illiterate may have more difficulties. They pointed out the importance of identifying patients who, due to these circumstances, perceive DIALOG+ as an obstacle to carrying out the consultation. It would also be more complicated to use it with people who are less inclined to use electronic devices.

Regarding situations in which DIALOG+ could be used, participants mentioned outpatient consultations, home care, day hospitals, functional rehabilitation and hospitalisation. In these departments, the tool could help to monitor therapeutic objectives, coordinate the performance of tasks by different members of the team in those aspects most related to their role, identify possible triggers of crises or the domains that were affected and that require an intervention after initial recovery. Given that some of the consultations were carried out after the start of the quarantine period, clinicians found that the dynamics could be adapted to teleconsultations. They pointed out the importance of using DIALOG+ in a context that allowed regular meetings.

They considered that other healthcare professionals, such as psychologists, social workers, therapists or general practitioners, could apply the tool, especially those working in programs for monitoring patients with mental illness in primary care, and even social care managers with no professional training in the health sector. In all cases, it would be necessary to train these personnel both in how to use DIALOG+ and how to talk to patients who have a serious mental illness.

DiscussionMain findingsThis study shows that DIALOG+ was valued positively by the majority of participants because it allows a broader assessment of life dimensions, provides didactic resources for follow-up and a structure that encourages dialogue and helps specify the search for and implementation of solutions. By inviting the patients to choose which areas they want to discuss at each consultation and to seek intervention alternatives, it encourages them to commit to their process and feel gratified by perceived improvements.

The tool is aimed at assessing health and its determinants, not the disease. It does not replace clinical judgement when identifying signs and symptoms of decompensation. Active affective or psychotic symptoms can be related to high scores in different areas and be an element of confusion if the clinician does not notice it. Due to the user-friendly design and simplicity of the proposal, both clinicians and patients consider that it can be easily adapted to their use and that it has the potential for other healthcare professionals to use it, as long as they have sufficient training and support, both in the use of technology and in talking to patients who have a serious mental illness. It could be used in departments other than outpatient consultations, such as partial or total hospitalisation, outpatient follow-up and telemedicine. However, it is less advisable for patients with cognitive impairment or who have severely disorganised thinking as part of a crisis. The most significant difficulties were due to the fact that DIALOG+ tended to extend consultation times, the clinicians had to perform a greater number of tasks, it increased their workload and emotional commitment, and it led to greater exhaustion. It should be noted that the longer consultation time was valued positively by the majority of patients.

Strengths and weaknessesOne of the strengths of the study is the fact that it was conducted at institutions intended for the regular care of patients with serious mental illness, allowing the investment required for its implementation to be reasonable and the training process to be simple. Public and private institutions were included for a more diverse observation. Clinicians had at least 3 months of experience at the institution and the patients had been attending consultations for at least 6 months, which made it easier for them to compare DIALOG+ with healthcare models in which they had participated before. The analysis plan was defined in advance, the categories were created based on the opinions of the participants, and the number of interviews was sufficient for the information in each category to be saturated. Its limitations include the fact that participants were part of the active group of a clinical trial and the scheduling of appointments was facilitated by the research team in order to comply with the design, which could bias their opinion. The clinicians made adjustments to the intervention framework so that implementation thereof was not homogeneous, a characteristic deriving from the nature of the practice. Given that the information was obtained from interviews, the experience of patients with poor ideation as a feature of their psychopathology may be under-represented.

Interpretation and implicationsPsychiatry follow-ups of patients with serious mental illness tend to focus on the prescription of medications and the search for signs and symptoms of decompensation, while other aspects of the patients’ lives are relegated to second place, generating the feeling that patients are not listened to enough. Both clinicians and patients have a different expectation about each other’s role, so it is pertinent to reflect on the options available for changing this dynamic and for improving the quality of the support. Positive impacts on doctor-patient communication and patient empowerment, supported by the resources made available by DIALOG+, are a strong reason for considering its implementation at regular consultations, given that these two aspects are the basis for obtaining better treatment outcomes. While producing data for individual follow-up and for planning interventions during the consultation, the tool can also be used as an indicator of compliance with objectives related to the perception of quality of life and the satisfaction of the healthcare providers with the departments. By being integrated into a psychotherapeutic intervention, this information could be made available to a larger population and be a component to be taken into account as a source of information for research and decision-making in the provision of services.

ConclusionsIntegration of DIALOG+ into the regular consultations of patients with a serious mental illness has the benefits of making it easier for these routine meetings to be therapeutically effective interventions. In order to integrate DIALOG+ into the Colombian healthcare system, it is necessary to make changes so that the original design is more flexible, and so that adapts better to the consultation time. It is also necessary to explore alternatives, such as an abbreviated version, making the tool available to the patients so that they can begin to use it independently and, based on the aspects that DIALOG+ addresses, work on identifying and strengthening care pathways involving a multidisciplinary team. DIALOG+ training should be aimed at handling the technology and reinforcing the skills of interacting with patients who have a serious mental illness. It is recommended that the use of DIALOG+ in clinical settings other than outpatient consultations and with healthcare professionals other than psychiatrists should be assessed.

FundingThis research was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (The NIHR Global Health Group on Developing Psycho-social Interventions; ref. 16/137/97) using aid from the government of the United Kingdom to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This study was funded and supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), supported and led by Queen Mary University of London. Its conduct was possible thanks to the support of the administrative and clinical staff and patients of the participating sites: Clínica Fray Bartolomé, Clínica la Inmaculada, IPS Campo Abierto de Bogotá and Hospital Departamental Psiquiátrico Universitario del Valle de Cali.

The study was presented before at the 59th Colombian Congress of Psychiatry as part of the symposium “Psychosocial interventions for severe mental disorders; DIALOG+ studies, meeting with volunteers and family intervention” on 18 October 2020.