To determine the influence of habits on depression in medical students from 7 Peruvian Regions.

MethodsAnalytical cross-sectional study of a secondary data analysis. The diagnosis of depression was obtained according to the Zung test result, with any level of this condition being considered positive. This was also compared with other social and educational variables that were important according to previous literature.

ResultsOf the 1922 respondents, 54.5% (n=1047) were female. The median age was 20 [interquartile range, 18–22]. According to the Zung scale, 13.5% (n=259) had some degree of depression. In the multivariate analysis, the frequency of depression increased with the hours of study per day (aPR=1.03; 95% CI; 1.01–1.04; p<0.001) and if the student worked (aPR=1.98; 95% CI; 1.21–3.23; p=0.006). On the other hand, the frequency of depression decreased on having similar meal schedules (aPR=0.59; 95% CI; 0.38–0.93; p=0.022), and having a fixed place in which to get food (aPR=0.66; 95% CI; 0.46–0.96; p=0.030), adjusted for the year of college entrance.

ConclusionsSome stressors predisposed to depression were found (working and studying more hours a day). On the other hand, having order in their daily routine decreased this condition (having a set place and times for meals).

Determinar la influencia de los hábitos en la depresión del estudiante de medicina de 7 departamentos de Perú.

MétodosEstudio transversal analítico de un análisis secundario de datos. El diagnóstico de depresión se obtuvo según el resultado del test de Zung, considerado positivo ante cualquier grado de esta condición. Además, se comparó esto con otras variables socioeducativas importantes según publicaciones previas.

ResultadosDe los 1.922 encuestados, el 54,5% (n=1.047) eran mujeres; la mediana de edad era de 20 [intervalo intercuartílico, 18-22] años. El 13,5% (n=259) tenía algún grado de depresión según la escala de Zung. En el análisis multivariable, incrementaron la frecuencia de depresión la mayor cantidad de horas de estudio por día (razón de prevalencias ajustada [RPa]=1,03; intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%], 1,01-1,04; p<0,001) y que el estudiante trabaje (RPa=1,98; IC95%, 1,21-3,23; p=0,006); en cambio, disminuyeron la frecuencia de depresión tener horarios similares para comer (RPa=0,59; IC95%, 0,38-0,93; p=0,022) y un lugar fijo donde conseguir sus alimentos (RPa=0,66; IC95%, 0,46-0,96; p=0,030), ajustado por el año de ingreso a la universidad.

ConclusionesSe encontró que algunos factores estresantes predisponen a la depresión (trabajar y estudiar más horas por día); en cambio, tener un orden en su rutina diaria disminuye esta condición (tener un lugar y horarios fijos para comer).

Depression is a mental disorder characterised by a state of despondency with feelings of sadness, causing changes in behaviour, the degree of activity and thinking and, in extreme cases, suicidal thoughts.1,2

Medical school is a recognised stressful environment3 with a high rate of depressive symptoms (12.9%) compared to the general population; depressive symptoms are more common in females than in males.4,5

The presence of depressive symptoms in medical students has been reported in a number of studies from different countries around the world, and relatively high prevalence rates have been found: 35% in Malaysia,5 40% in Trinidad and Tobago,3 52% in Pakistan6 and 67% in the United Kingdom.7 The stress to which medical students are subjected causes emotional reactions that often have a negative effect on academic performance, physical health, psychosocial well-being and therapeutic decisions.5

In Peru, some studies have found the prevalence of depression to be around 4.6% in students of health sciences.8,9 However, in a study of fourth-year medical students, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 29.9%,10 an alarming figure when we consider the repercussions on the physical and mental health and the training of these future healthcare professionals, and something that could have later consequences on the service they provide to the population.11 With this in mind, the objective of the study was to determine the influence of habits on depression in medical students from seven different provinces in Peru.

MethodsMulticentre cross-sectional study; an analysis of secondary data was carried out based on a study of medical students in Peru.12

The study population was medical students from seven cities in Peru (Lima: Universidad Ricardo Palma; Ucayali: Universidad Nacional de Ucayali; Ica: Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga de Ica; Cajamarca: Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca; Cusco: Universidad San Antonio Abad De Cusco; Huancayo: Universidad Peruana Los Andes; Piura: Universidad Privada Antenor Orrego and Universidad César Vallejo). Convenience sampling was used to select participants.

We included students enrolled in the 2015-I cycle, who were in first year to sixth year (before becoming residents) and who agreed to participate in the study. For data collection, a self-applied survey was used, consisting of general and consumption data.

The primary endpoint was depression, according to the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale, for which Cronbach's alpha=0.85; sensitivity of 94.7% (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 90.5–99.7); specificity of 67.0% (95% CI, 56.3–76.3); positive predictive value of 37.5% (95% CI, 24.3–52.7) and negative predictive value of 98.4% (95% CI, 90.2–99.9) were reported.13

The independent variables were the characteristics of the medical students: gender, marital status, age, academic semester, average hours of study per day, not having passed a year, financial dependence (on their family, if they worked or both) and having a partner, similar meal times and a fixed place to obtain food. The information collected was ordered in a Microsoft Excel 2010 program database. The analysis was divided into two phases: a descriptive phase and an analytical phase. For the descriptive phase, we determined the absolute and relative frequencies of the categorical variables. We also obtained the medians [interquartile range] of the quantitative variables, after assessment of normality with the Shapiro–Wilk statistical test. For the analytical phase, we worked with a 95% confidence interval. For the bivariate and multivariate statistical analysis, the categorical variables were crossed using generalised linear models, using the Poisson family, the log link function, robust models and considering the university as a cluster; the gross prevalence ratios (PR) and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and their 95% CI were obtained. We considered p<0.05 as statistically significant. The main project was approved by an ethics committee (OFFICE No. 262-OADI-HONADOMANI.SB-2015).

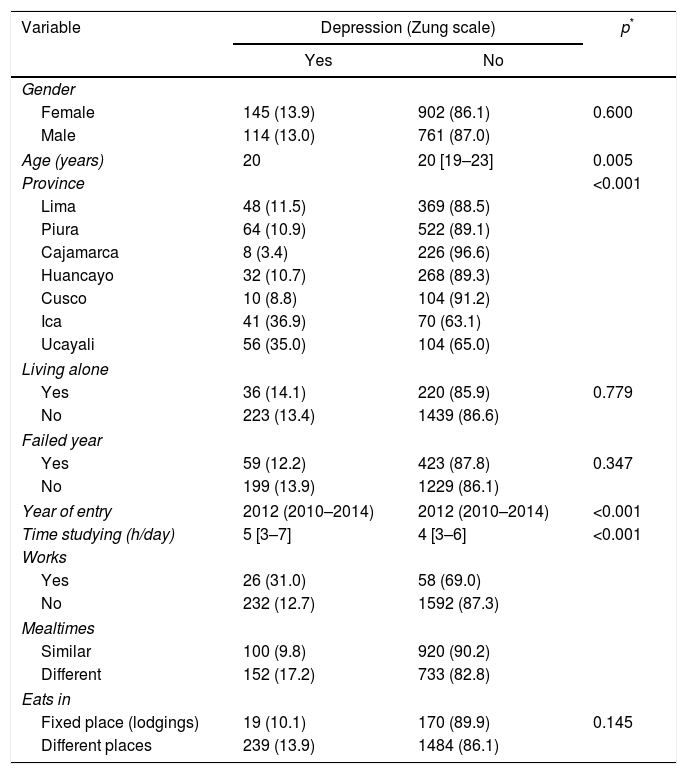

ResultsOf the 1922 surveyed, 54.5% (n=1047) were female and the median age was 20 [18–22]. According to the Zung scale, 13.5% (n=259) had some degree of depression. The main results are shown in Table 1.

Socio-educational characteristics of the medical students from seven different provinces in Peru, according to whether or not they had depression.

| Variable | Depression (Zung scale) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 145 (13.9) | 902 (86.1) | 0.600 |

| Male | 114 (13.0) | 761 (87.0) | |

| Age (years) | 20 | 20 [19–23] | 0.005 |

| Province | <0.001 | ||

| Lima | 48 (11.5) | 369 (88.5) | |

| Piura | 64 (10.9) | 522 (89.1) | |

| Cajamarca | 8 (3.4) | 226 (96.6) | |

| Huancayo | 32 (10.7) | 268 (89.3) | |

| Cusco | 10 (8.8) | 104 (91.2) | |

| Ica | 41 (36.9) | 70 (63.1) | |

| Ucayali | 56 (35.0) | 104 (65.0) | |

| Living alone | |||

| Yes | 36 (14.1) | 220 (85.9) | 0.779 |

| No | 223 (13.4) | 1439 (86.6) | |

| Failed year | |||

| Yes | 59 (12.2) | 423 (87.8) | 0.347 |

| No | 199 (13.9) | 1229 (86.1) | |

| Year of entry | 2012 (2010–2014) | 2012 (2010–2014) | <0.001 |

| Time studying (h/day) | 5 [3–7] | 4 [3–6] | <0.001 |

| Works | |||

| Yes | 26 (31.0) | 58 (69.0) | |

| No | 232 (12.7) | 1592 (87.3) | |

| Mealtimes | |||

| Similar | 100 (9.8) | 920 (90.2) | |

| Different | 152 (17.2) | 733 (82.8) | |

| Eats in | |||

| Fixed place (lodgings) | 19 (10.1) | 170 (89.9) | 0.145 |

| Different places | 239 (13.9) | 1484 (86.1) | |

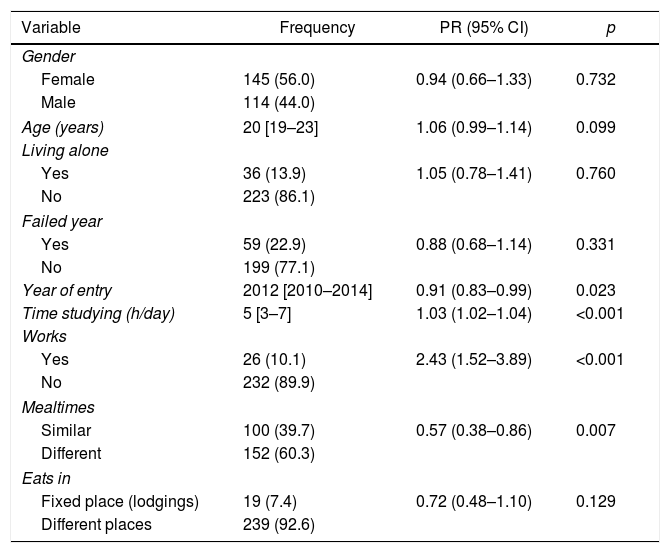

In the bivariate analysis, the variables associated with having some degree of depression were the year of entry (p=0.023), the average hours studying per day (p<0.001), working to maintain themselves financially (p<0.001) and having fixed times for eating (p=0.007) (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis of depression according to socio-educational factors of medical students from seven different provinces in Peru.

| Variable | Frequency | PR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 145 (56.0) | 0.94 (0.66–1.33) | 0.732 |

| Male | 114 (44.0) | ||

| Age (years) | 20 [19–23] | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 0.099 |

| Living alone | |||

| Yes | 36 (13.9) | 1.05 (0.78–1.41) | 0.760 |

| No | 223 (86.1) | ||

| Failed year | |||

| Yes | 59 (22.9) | 0.88 (0.68–1.14) | 0.331 |

| No | 199 (77.1) | ||

| Year of entry | 2012 [2010–2014] | 0.91 (0.83–0.99) | 0.023 |

| Time studying (h/day) | 5 [3–7] | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.001 |

| Works | |||

| Yes | 26 (10.1) | 2.43 (1.52–3.89) | <0.001 |

| No | 232 (89.9) | ||

| Mealtimes | |||

| Similar | 100 (39.7) | 0.57 (0.38–0.86) | 0.007 |

| Different | 152 (60.3) | ||

| Eats in | |||

| Fixed place (lodgings) | 19 (7.4) | 0.72 (0.48–1.10) | 0.129 |

| Different places | 239 (92.6) | ||

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: prevalence ratio.

The frequencies are expressed as n (%) or median [interquartile range]. The gross PR, the 95% CI and the p values were obtained with generalised linear models, with Poisson family, log link function, robust models and adjusting per province as a cluster.

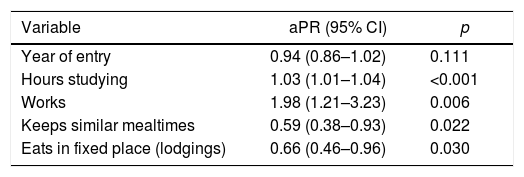

In the multivariate analysis, the depression rates increased the more hours they studied per day (aPR=1.03, 95% CI, 1.01–1.04, p<0.001) and if the student worked (aPR=1.98; 95% CI, 1.21–3.23, p=0.006). However, depression rates decreased with keeping similar mealtimes (aPR=0.59, 95% CI, 0.38–0.93, p=0.022) and having a fixed place to obtain food (aPR=0.66; 95% CI, 0.46–0.96, p=0.030) adjusted for the year of entry to the university (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of depression according to socio-educational factors of medical students from seven different provinces in Peru.

| Variable | aPR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Year of entry | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 0.111 |

| Hours studying | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <0.001 |

| Works | 1.98 (1.21–3.23) | 0.006 |

| Keeps similar mealtimes | 0.59 (0.38–0.93) | 0.022 |

| Eats in fixed place (lodgings) | 0.66 (0.46–0.96) | 0.030 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio.

The aPR, the 95% CI and the p values were obtained with generalised linear models, with Poisson family, log link function, robust models and adjusting per province as a cluster.

Depression has been studied in Peruvian populations with rates being found of up to 32%.14 However, very few studies have investigated depression in medical students. We therefore felt that it was important to determine both the rate and degree of depression in this student population15 and identify possible causative factors, with a view to preventing those which can be modified. With this being the largest study to be conducted in Peru on this subject to date, we were addressing an issue which had not been well researched.

In countries such as the United States, depression rates of 25% have been identified in medical students, and associations have been found with the presence of other comorbidities, such as alcohol abuse/dependence.16 Several studies have been conducted on this subject in Peru but, as each applied different instruments, the prevalence rates varied. In our study, 13% of students were found to have some degree of depression, lower than that found on a national scale; previous studies reported prevalence rates of 19%, 22% and 30% in medical students at public universities, with up to 2% suffering from severe symptoms,17,18 and a prevalence of around 30% in private universities.10,19 The reason for such variation may be that, prior to this study, none of the research studies had covered all universities, whether public or private.

It was also found that having certain stressors increases the depression rate, i.e. having a job and studying more hours per day. This is consistent with the literature; Gutiérrez et al.20 reported that the academic situations that generate the most stress in the students are oral presentations and the academic load, understood as the volume of study topics and, as a consequence, more hours per day.

Lastly, having a certain order in the daily routine was associated with having lower rates of depression; this was measured by indirect variables (having similar mealtimes and a set place to eat). This is comparable with a study conducted by Guzmán which reports an association between poor eating habits and suffering from psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety.21 We recommended that further research be set up to investigate other social and educational habits that might be related to depression and other mental symptoms.

Our study has the limitation of selection bias as it is a secondary data analysis. This does not allow for greater diversity of variables to measure and makes it dependent on the non-randomised sampling of the original study, thereby making it impossible to adequately use the confidence intervals. However, no attempt was made to find the prevalence for each university; randomised sampling of each of the faculties would have been required to do that.

We have concluded from the results that, although depression is not very common among medical students in Peru, it is positively associated with variables that could be considered stressful and negatively associated with variables that reflect a certain order in a student's routine.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vargas M, Talledo-Ulfe L, Heredia P, Quispe-Colquepisco S, Mejia CR. Influencia de los hábitos en la depresión del estudiante de medicina peruano: estudio en siete departamentos. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:32–36.